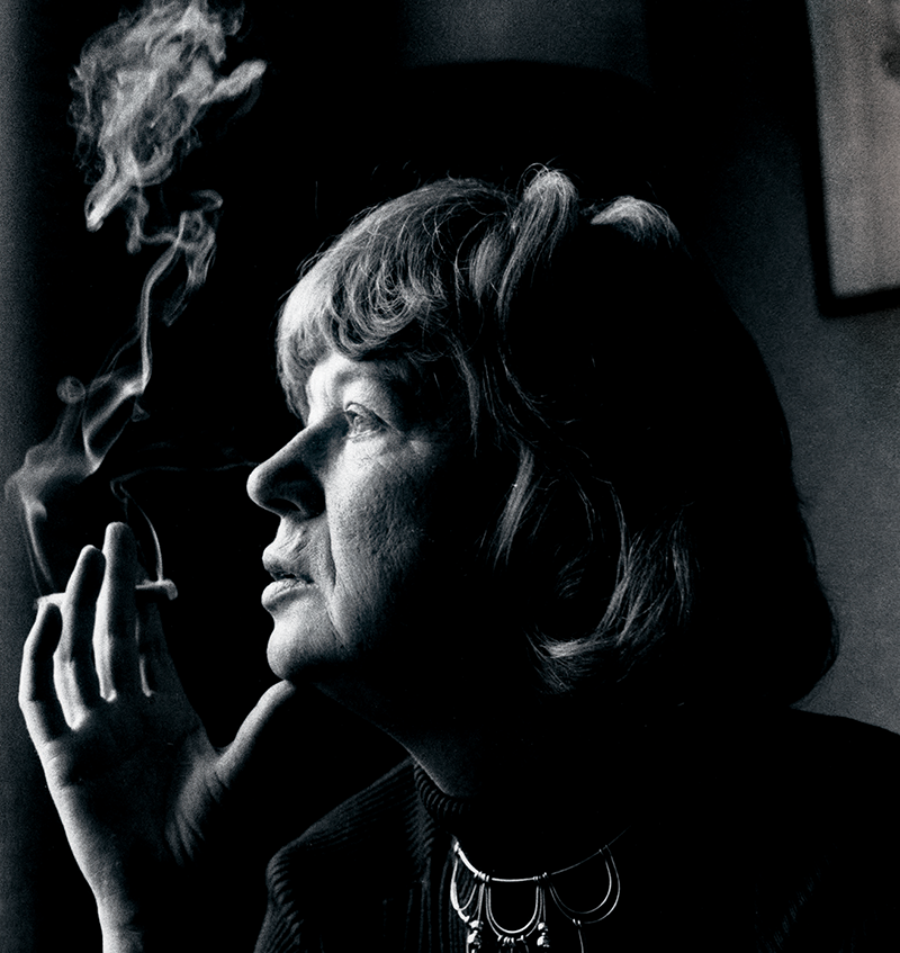

Photograph of Tove Ditlevsen © Jette Ladegaard/Ritzau Scanpix/AP Images

Discussed in this essay:

The Copenhagen Trilogy: Childhood, Youth, Dependency, by Tove Ditlevsen. Farrar, Straus and Giroux. 384 pages. $30.

Are you sad? Unmoored? Confused? As a child were you deemed “sensitive,” as a young person “fragile”? Do others comment that you seem emotionally unsuited to the life you admittedly can’t believe you’re still living? Are your feelings often hurt? Do you believe that everything used to be better, but struggle to come up with examples of how? Does the thought of reality make you want to go back to bed? Are you in bed right now?

If so, I have some book recommendations for you. In recent years, the feminist project of uncovering “forgotten” female writers and artists has yielded—among other fruits—a steady stream of “rediscovered” mid-twentieth-century works that those of us prone to weltschmerz may find pleasantly, or painfully, “relatable,” to use a contemporary publicity standard. My favorites are those that fall into a genre I call, affectionately, “sad girls in Europe.” Experimental yet accessible, the books depict a female self fragmented by history, circumstance, and failing relationships that cannot be entirely chalked up to history or circumstance, and they’re written in prose that is consummately composed even as the protagonist’s life and mind are falling apart. Being sensitive does not mean being precious; it can produce a shaky resilience, and a ruthless clarity that illuminates the self as well as the rest of the world. Textual weirdness is dutifully contextualized: “For a long time I have been lonely, cold and miserable,” begins Anna Kavan’s story “Going Up in the World.” “I told Helen my story and she went home and cried,” goes the opening to Barbara Comyns’s novel Our Spoons Came from Woolworths. Similarities between the author’s life and work need not be defensively rejected; there is a sense among these writers that distinctions between what is and is not “reality” are hopelessly beside the point—all experience is real. Kavan, Comyns, Susan Taubes, and Helen Weinzweig are a few new additions to a canon that includes Jean Rhys, Marguerite Duras, and even, you could argue, Virginia Woolf. (In this framework, dreams of Europe, hallucinations of Europe, and the United Kingdom all qualify as “in Europe.”) As a bonus for those of us often lacking life force, the books are usually pretty short.

The brief biography accompanying advance copies of the reissue of Tove Ditlevsen’s The Copenhagen Trilogy, a set of compact memoirs translated by Tiina Nunnally and Michael Favala Goldman, announces her as one of these authors.

Tove Ditlevsen was born in 1917 in a working-class neighborhood in Copenhagen. Her first volume of poetry was published when she was in her early twenties, and was followed by many more books, including her three brilliant volumes of memoir, Childhood (1967), Youth (1967), and Dependency (1971). She married four times and struggled with alcohol and drug abuse throughout her adult life until her death by suicide.

It’s all there: the historical obstacle (working class, 1917, she/her), the essential talent (early twenties), the foregrounded self (brilliant memoir) tragically distorted (the entire last sentence).

Something about this biography irks me. The mention of four marriages is a little unfair; the first two were over by the time she was twenty-eight. But the real problem is not that the details are wrong—many of them have even been removed from the final text of the book. The real problem is that they indicate the degree to which the “sad girls in Europe” have become a marketing cliché, elevated from the domain of steadfast bloggers and thoughtful small presses to the interest of major cultural institutions, as with the New York Times’s Overlooked obituary series, or the wildly Instagrammable 2018–19 Hilma af Klint show at the Guggenheim.

Is that bad? Not necessarily. But when great work finds a wider audience, it often finds more opportunities to be misinterpreted. To summarize a life as consisting of four marriages, alcohol and drug abuse, and death by suicide not only glamorizes hardship; it shines an ugly fluorescent light on the writing, washing out the aesthetic choices that render Ditlevsen’s representation of those experiences so affecting. It also makes it difficult not to read her life’s work in the context of its tragic, certainly not predestined end. Ditlevsen does not fit neatly in the lineage of hot messes whose writing can only be appreciated in light of their unjustly female circumstances and put-upon psyches; she was a writer first and a mess second. She was not ignored by the establishment; she was simply celebrated somewhere other than the United States or the United Kingdom. She won many awards in her lifetime, and one of her novels, Barndommens gade (Childhood Street), was adapted for film in the 1980s and voted one of the best Danish books of the century in 1999. Her work is now taught in Danish schools.

In addition to her dozens of books of poetry and prose, in 1956 Ditlevsen’s famously clear-eyed approach to the “small, everyday problems” of life as a woman led to a pragmatic advice column in the women’s magazine Familie Journal, and her more than four thousand contributions were recently published as a collection and featured in a documentary series produced by the Danish Broadcasting Corporation. She has the Scandinavian talent for balancing emotion and detachment, for assessing dramatic feelings directly, and for describing insanity sanely; maybe it has something to do with social democracy and long, dark winters. (She once gave her thoughts on hygge, the Danish concept of coziness that went viral a few years ago: “a fickle guest which comes when it suits it and most often when no one has called for it.”) Even though she wrote all three volumes of the trilogy, as well as her last novel, Wilhelm’s Room, during hospital stays, the publication of Dependency shocked many readers, who hadn’t known she was an addict. “The big advertising roar has been appalling and I fear that the book’s literary intention is drowning in sensation,” she told an interviewer. While it’s natural to be drawn to an author’s life story, even one like this—it suggests, rightly, that she had experiences that drew her close to what is difficult to approach—one’s life story is supposed to serve the work, not the other way around. What’s more, the advertising roar isn’t exactly feminist.

Ditlevsen was born in Copenhagen’s Vesterbro district in 1917, though she was known to claim it was 1918, as she does in Childhood. She introduces the fib as follows: “There exist certain facts. They are stiff and immovable, like the lampposts in the street, but at least they change in the evening when the lamplighter has touched them with his magic wand.” She grew up sharing a bedroom with her parents, in a two-room apartment in the back of their building; her older brother, Edvin, who “knows everything—about the world and society, too,” slept on the sofa.

Her childhood was filled with tiny heartbreaks and traumas. Her mother, Alfrida, a housewife, was volatile, “mysterious and disturbing”; every morning Tove would wake up hoping to find her in a good mood, and throughout the day the “no-man’s-land” between them would become more and more dangerous; her mother’s “violent and irritated movements” while getting dressed, “as if every piece of clothing were an insult to her,” would destroy the young girl’s spirit. Alfrida bitterly resented her husband, Ditlev; the way she talked about him, as a “dark spirit who crushes and destroys everything that is beautiful and light and lively,” did not sound to Tove like her father at all. Ditlev, a laborer and an avowed socialist, was “big and black and old like the stove, but there is nothing about him that I’m afraid of.” Though she could gather information about her mother through careful observation and canny assessment, everything she knew about her father she was “allowed to know, and if I want to know anything else, I just have to ask.”

Outside, the cast of neighborhood characters includes Scabie Hans; his thirteen-year-old lover, Rapunzel; Tin Snout; Curly Charles; The Hollow Leg (aka Tove’s uncle Carl); Pretty Lili; and Pretty Ludvig. Neither of the latter are pretty; writing from the perspective of her childhood self, as she does throughout, Ditlevsen explains, “Everything that is ugly or unfortunate is called beautiful, and no one knows why.” Older girls gossip and intimidate her from their regular perch in “the trash-can corner” of the courtyard. She is surrounded by drunks, prostitutes, fights, and unwanted pregnancies, a possible future she has quickly learned to fear. Her father is never secure in his job, and aging out of the ability to find a new one. Sometimes there is not enough food, and the family lives for days on coffee and stale pastry. On top of all this, Ditlevsen is a delicate, observant child, prone to finding indications of hopelessness in daily life. When she realizes her parents got married only two months before her brother was born—they tell her the firstborn only gestates for two months—she thinks that “the worst thing about grownups” is that “they can never admit that just once in their lives they’ve acted wrongly or irresponsibly. They’re so quick to judge others, but they never hold Judgement Day for themselves.”

What might seem in other writers a retroactive precocity is believable here. Ditlevsen is self-deprecating and effective at conveying the fish-eye view of a child in a claustrophobic environment; she understands that part of the memoirist’s job is to remember how life felt and synthesize it in a way she couldn’t have at the time. “Childhood is long and narrow like a coffin, and you can’t get out of it on your own,” she writes. “It’s there all the time and everyone can see it just as clearly as you can see Pretty Ludvig’s harelip.” Her embarrassment at being seen clearly, as she sees others, shapes her later resistance to reality. From a young age, she wants to grow up and become a poet—crucially, one who earns money—in part as a kind of defense mechanism against the world’s manifold cruelties. When her mother’s subtle hostility would emerge, she writes, lines “began to crawl across my soul like a protective membrane,” until one day her bad moods ceased to matter. Still, childhood becomes a symbol of lifelong trauma:

On the sly, you observe the adults whose childhood lies inside them, torn and full of holes like a used and moth-eaten rug no one thinks about anymore or has any use for. You can’t tell by looking at them that they’ve had a childhood, and you don’t dare ask how they managed to make it through without their faces getting deeply scarred and marked by it. You suspect that they’ve used some secret shortcut and donned their adult form many years ahead of time.

No one in her family supported her aspiration to become a poet, of course. Her father might have—he apprenticed as a reporter at sixteen, and he dreamed of writing for the rest of his life—but he had strictly ideological tastes, and he didn’t believe girls could be poets. He approves when his daughter returns from the library with Les Misérables—though he doesn’t like it when she “didactically and self-importantly” corrects his pronunciation of “Hugo”—but when she brings home poetry collections, he tells her that “they have nothing to do with reality,” not realizing that that is precisely the appeal. (In turn, he is subjected to similar remarks from his wife: “People turn strange from reading,” she scoffs when she finds him holding a book. “Everything written in books is a lie.”) When Edvin finds his sister’s secret notebook full of poems, he laughs at them hysterically and tells her, “You’re really full of lies.”

He has a point—the poems are outrageous. Ditlevsen’s romantic attachment to poetry showed in her first efforts, many of which are dryly reproduced in these memoirs. “I thought my poems covered the bare places in my childhood like the fine, new skin under a scab that hasn’t yet fallen off completely,” she writes. “Would my adult form be shaped by my poems? I wondered.” Copying hymns, ballads, and poems from the end of the previous century, she writes about “a wanton life filled with interesting conquests” or else composes what is best described as Victorian emo. After she returns from three months in the hospital, where she recovered from diphtheria, she notes, “I wrote poetry exclusively like this”:

Wistful raven-black night,

kindly you wrap me in darkness,

so calm and mild, my soul you bless,

making me drowsy and light . . .Quietly I sleep,

blessed night, my best friend.

Tomorrow I’ll wake to life again

my soul in sorrow deep.

She matures into no mere moody teenager; she is deeply depressed and begins to think of death “as a friend.” Edvin moves out and gets a job as a painter’s apprentice, which gives him a chronic cough and damages his lungs. Her friends begin meeting boys; her enduring virginity is commented upon. Soon, her aversion to being a child transforms into dread of what faces her as an adult. She leaves school at fourteen, to the understanding regret of her teachers, in order to work.

At the beginning of Youth, she quits or is fired from a series of jobs. (Among the bloopers is a scene in which she attempts to wash a grand piano because she has been instructed to “brush all of the furniture with water,” and deciding pianos must count as furniture, covers it with hundreds of fine scratches; her mother helps her ghost the boss.) Regarding politics, she is always sort of with it but not especially interested. When her boyfriend discusses socialism with her father, she writes, “I like to hear him develop this plan, because it would further my own personal interests if the poor came to power.” She needs to find a husband, because she wants to have children, and because “a girl has to be supported.”

As she begins going to dances and parties, it’s hard to ignore the parallels between her blossoming life and her mother’s memories of a lively youth, with “a new boyfriend every night,” cut short by her relationship with the dark spirit that is Ditlev. The ease with which Tove resists her family’s skepticism about literature doesn’t translate to other lessons they taught her. At eighteen, she moves into a boardinghouse and rushes into an engagement so she can lose her virginity—“I’m not very passionate,” the boy tells her; “I don’t think I am either,” she replies—even though many of her friends aren’t at all held back by similar beliefs. The pair break it off, but she becomes increasingly antsy.

The opportunities for a young working-class woman to publish poetry during the Great Depression were limited, but they did expose her to several potential husbands. A boy introduces her to an editor who reads some of her juvenilia and promises to help her when she’s a little older; before she is a little older, she happens to read in the newspaper that the editor has died. A friend hoping to get the pair of them jobs as chorus girls introduces her to an older man who lets her borrow books and discusses them with her; one day she goes to visit him and finds his entire building has been demolished. Finally, at a dance, a boy tells her about a journal, Wild Wheat, that publishes young and unknown writers. She sends some poems to the editor, Viggo F. Møller, who writes back that he would like to publish one—“To My Dead Child,” a poem about a miscarriage, something she hasn’t experienced—and to meet her. She tells her mother, who jokes that the editor probably wants to marry her. “If he’s single, I have nothing against marrying him. Entirely sight unseen.” This, too, ends abruptly, but first she publishes a book of poems, Pigesind, or A Girl’s Mind, just as England declares war on Germany.

The third volume of the trilogy, Dependency, begins with Tove having married Viggo F., who is kind, impotent, the center of a glamorous literary scene, somewhat repugnant, and much too old for her. She sends her first novel, A Child Was Harmed, to a publisher, and it is rejected with a note “insinuating that I have been reading too much Freud. I don’t even know who Freud is”—a darkly comic omen. She sells it to the next publisher. The rest of the book descends harrowingly; Tove’s star rises as her life sputters and then explodes. (The book’s Danish title, Gift, means both “poison” and “married.”) Her characteristic long paragraphs and simple sentences create a confessional effect. In fewer than 150 pages, Dependency summarizes each of Ditlevsen’s four marriages, including the extremely bad one. From Viggo F., she has an affair with a classic scoundrel and from there swings to an economics student, Ebbe, who becomes her second husband. He is suitable except that he doesn’t want to have a child, as she does; when they do, he begins drinking heavily as well as dabbling in the resistance to the German occupation. Another pregnancy ends in an illegal abortion. Then, at a Tubercular Ball—an event hosted at a dormitory for patients being treated for TB—she has a one-night stand with an intense, flattering, “quite ugly” doctor. “You get pregnant just walking through a draft,” her friend sighs.

Like her 1968 novel The Faces, which Nunnally describes as “strongly autobiographical,” Dependency turns into a relentless, highly controlled account of the experience of madness. Tove visits the doctor, Carl, to ask him to help her “get rid of it.” He tells her he’ll perform a curettage, no problem, and also he’s been reading everything she has ever written, they should get married, their child would be lovely, and by the way, “I have to tell you that I am a little crazy.”

You think that it would be pretty far to go from here to weighing sixty-six pounds and being permanently deaf in one ear, but actually it is not that far at all. Tove remains interested only in the abortion until Carl gives her the painkiller that goes with it, which has her returning his confession of true love. As the drug begins to wear off on her way home, she feels “as if a gray, slimy veil covers whatever my eyes see” and she becomes “preoccupied with the single thought of doing it again.” Two sentences later, we learn that “Ebbe has since died, but whenever I try to recall his face, I always see him the way he looked that day I told him there was someone else.” Ebbe asks, “Do you think he can give you an outlook on life?” and she responds, “I don’t think an outlook on life is something people give one another.”

Ditlevsen is a master of slow realization, quick characterization, and concise ironies. She becomes catastrophically addicted to Demerol, and to pills, almost immediately. She moves in with Carl and decides to have a baby with him in order to “bind [him] to me even more.” After a while, to get more Demerol she lies to him about having chronic earaches. This is the moment we realize he really is crazy; a friend of his comes over and tells Tove that Carl has become fixated on researching ear maladies. It is apparent, but never certain, that Carl is giving her drugs to control her; in an earlier scene, he shows up to a nice dinner she’s at with Evelyn Waugh and makes her come home. Carl’s obsession with her fake ear problem intensifies. An ear doctor tells her nothing is wrong; Carl demands a second opinion from the doctor’s rival. Tove is ultimately convinced to go along with an unnecessary surgery by the prospect of “all the Demerol I want.” She wakes up in the kind of pain that makes her realize she had never experienced real pain before, but it doesn’t matter much: “When we got home I had a shot and thought, This is how I always want to live. I never want to return to reality again.”

The appeal of a memoir is not that it contains stable facts, but rather a stable perspective, and part of the propulsion of these odd books is Ditlevsen’s steadiness. Eventually, Tove crawls to the phone and gets herself admitted to a rehab facility, and Carl taken to an asylum; they never see each other again. Unlike in The Faces, where she uses a nearly constant stream of (incredible) metaphors to represent the protagonist’s untrustworthy feelings and hallucinations, here Ditlevsen is declarative: at the hospital, the sheets are “always full of my excrement”; the intervals between her shots of Demerol are excruciatingly long; she sees herself in the mirror and sobs, “I look like I’m seventy.” As she recovers, haltingly, she meets her fourth husband, the editor Victor Andreasen, whom she has heard about from mutual friends. Their marriage lasts twenty years, almost as long as her addiction and her discomfort with the feeling of “reality under my skin.”

Though she was a prolific writer until her death, Ditlevsen felt in her later years that, despite her fame, she hadn’t gotten as much respect as she deserved; following her divorce from Andreasen in 1973, she was overlooked for a major prize and attempted suicide. Her unlikely success as an advice columnist must have had to do with her ability to see herself as clearly as she saw others, which involved seeing how she was different.

When I got that column, I thought: You can never do that. If I was already having a hard time coping with my own problems, how would I deal with other people’s problems? But then I discovered that it actually went very well, precisely because I myself have not walked the straight, beaten path from cradle to grave.

Throughout the memoirs, normalcy and reality are tense, tortured concepts; Ditlevsen writes that she knew she was not “normal” and desperately wished she were. Barring that, she writes of “the curtain that is always hanging between me and reality” which “turns gray and perforated, like a spider web” when something hard and immovable—an unwanted pregnancy, or the symptoms of a comedown—happens to her. It’s difficult to understand this: Her hindsight is subtle and non-judgmental, and she seems neither to derive strength from nor to emphasize her own weakness in writing about herself. There doesn’t seem to be much between her mind and the rest of the world.

But for people whose sense of reality is volatile, the written word and its shifty “lies” offer a strange kind of stability. Taubes described this in her recently reissued novel Divorcing:

Books were better than dreams or life . . . you know where you are: you’re in a book . . . You can be dreaming and not know it. You can be awake and wonder if it’s a dream and not believe it. But a book is simply and always a book—you can be sure of that. And with a book, whether you’re reading it or writing it, you are awake.

What is superficially unstable is revealed to have a much deeper connection to real events than it appears; it’s the book’s separation from reality that allows it to express what is true. Similarly, when Ditlevsen published her first poetry collection, she thought, “The book will always exist, regardless of how my fate takes shape.” To bring things back to marketing, this means you don’t have to advertise that an author died by suicide on the back of her book. The work is important; the fate is merely a fact.