Mountains in the Snow, by Erich Heckel © akg-images/Artists Rights Society, New York City

Philippe Sands’s remarkable 2016 book, East West Street: On the Origins of “Genocide” and “Crimes Against Humanity,” weaves together the history of his family and that of two concepts central to his chosen profession as an international human-rights lawyer. All strands of that thought-provoking exploration run through the city now known as Lviv (formerly Lemberg and Lwów), where Sands’s Jewish forebears lived and were massacred during the Second World War, and where the two lawyers who conceived of the terms “genocide” and “crimes against humanity” were originally educated.

In the course of his research, Sands came to know Niklas Frank, son of the notorious Hans Frank, the Nazi governor-general of the occupied Polish territories—which included Galicia, and hence the city of Lwów—who was directly responsible for the slaughter of millions of people. Hans Frank was tried at Nuremberg and subsequently executed, a fate Niklas applauds: his own memoir In the Shadow of the Reich condemns his father’s actions. Through Niklas Frank, Sands was introduced to Horst von Wächter, the son of Otto von Wächter, a high-ranking Nazi and colleague of Hans Frank, who was first the governor of Kraków and then of the District of Galicia. Unlike the younger Frank, the younger von Wächter is a lifelong apologist: “I know the system was criminal, that my father was part of it, but I don’t think of him as a criminal.”

Sands made an extraordinary film about both men—each born on the cusp of war in 1939—that explores their relations to their personal legacies. What Our Fathers Did (2015) has at its center a trip the three men took to Lviv, where Horst—mild, amiable, lost-seeming—repeatedly refuses, to the frustration of Sands and Frank, to acknowledge his father’s complicity in the Nazi atrocities.

Sands’s new book, The Ratline: The Exalted Life and Mysterious Death of a Nazi Fugitive (Knopf, $30), picks up where the film left off. Arguably, this damning and meticulously researched biography of a leading but lesser-known Nazi exists, above all, to convince Horst of his father’s culpability. Otto von Wächter was involved in the Austrian Nazi movement from its earliest days, having participated in the July Putsch of 1934 that led to the assassination of Chancellor Engelbert Dollfuss of Austria. Himself the son of an Austrian First World War hero, Otto never wavered in his commitment to Nazism, and he was swiftly promoted through the party’s ranks, in each post amply salaried and awarded luxurious (stolen) accommodations. Along with his wife, Charlotte, and a growing brood of children (eventually six), he was close to Hitler’s inner circle. (According to Sands, Charlotte maintained that “the time with Hitler on the balcony of the Heldenplatz would always be ‘the best moment of my life.’ ”) In due course, Otto signed orders expelling sixty-eight thousand Jews from Kraków, and consigned the remaining fifteen thousand to the newly created Jewish ghetto. In Galicia, he oversaw the murder of tens, perhaps hundreds, of thousands. At the end of the war, he hid in the Alps to avoid prosecution. He resurfaced in Rome in 1949, where he suddenly took ill and died while under the care of Bishop Alois Hudal, an Austrian Catholic with Nazi sympathies.

Otto and Horst von Wächter, circa 1942. Courtesy Alfred A. Knopf

Nonetheless, Horst maintains his father’s innocence. Sands records in The Ratline that “the visit to Ukraine caused a rift between Niklas and Horst,” as Niklas came to feel that his friend was “really a Nazi.” There is, in Horst, a fascinating psychology to explore: what has prompted this man, who claims to acknowledge the atrocities of Nazism, to spend his life denying his father’s involvement? But Sands is a lawyer, not a novelist, and his book is a carefully researched prosecution, not an exploration of motive.

The latter sections of the book involve an apparent digression on account of the author’s research: Sands, seeking to ascertain whether Otto von Wächter died of natural causes or, as had been bruited, was murdered, ultimately brings to light unsettling details about the Ratline in his title. Also referred to as the Reich migratory route, the Ratline was “an escape route used by Nazis to flee from Europe to South America, [which had been] identified as a place of safety governed by sympathetic leaders.” (For many of us, it is understood as the backstory to Seventies films such as Marathon Man and The Boys from Brazil.) This exfiltration path generally led through Rome, and individuals affiliated with the Vatican seem to have been repeatedly involved. This was not in dispute. What Sands discovers, however, is the presence of double agents, and the awareness, and perhaps complicity, of American intelligence agencies, whose primary preoccupation at the time was anticommunism. His dogged persistence in following leads—with the help of several historians and none other than David Cornwell, aka John le Carré—ultimately brings him to a story of coincidental human connection as unexpected as the one in East West Street, which was that his grandfather and the two legal scholars responsible for framing the Nuremberg trials all studied under the same professor in interwar Lwów. In The Ratline, Sands has once again written a riveting and insightful historical page-turner that proves to be part History Channel, part W. G. Sebald.

A different legacy of the Third Reich in the United States emerges in Alexander Wolff’s memoir, Endpapers: A Family Story of Books, War, Escape and Home (Atlantic Monthly Press, $26). Wolff, who spent a year in Germany researching his family history, is best known as a longtime writer for Sports Illustrated. As his imposing German aunt Maria once told him, “Sport—it’s as if you’re a society columnist. It’s not quite what your parents expected.”

Wolff’s paternal grandfather was the German publisher Kurt Wolff, whose first wife, Elisabeth Merck, was heiress to the pharmaceutical fortune, and who, with his second wife, Helen, found refuge in the United States in 1941 thanks to Varian Fry and the Emergency Rescue Committee. Once settled in New York, they established Pantheon Books, where they employed, among other recent arrivals, Jacques Schiffrin, the founder of the Pléiade editions in France, whose son, André Schiffrin, would also work for Pantheon before starting the New Press in 1992, and whose granddaughter, Natalia Schiffrin, would marry Philippe Sands.

Couples in Conversation, by Oskar Kokoschka, from The Dreaming Boys, published in 1917 by Kurt Wolff Verlag. Image © Erich Lessing/Artists Rights Society/Art Resource, New York City

The global literary legacy of Kurt and Helen Wolff cannot be overstated. In Germany, from 1913 onward, Kurt Wolff’s eponymous house published Franz Kafka, Karl Kraus, and Heinrich Mann, as well as art books by Oskar Kokoschka and Paul Klee. Forced to flee Germany in 1933 due to his “degenerate” publishing business and his Jewish heritage, Kurt Wolff left behind two children from his first marriage, Maria and Niko, who lived with their mother and her new husband. (In spite of their biological father’s heritage, both managed to procure Aryan identity papers.) Until the onset of the war, the children spent summers with Kurt and Helen on the Côte d’Azur, but their narratives then diverged sharply.

The Wolffs established themselves in the United States and, in time, proved indispensable in introducing European writers to an American audience—not only those whom Wolff had published in Germany and the French writers brought in by Schiffrin père, such as André Gide, Albert Camus, Paul Claudel, and Charles Péguy, but also writers of younger generations, among them Boris Pasternak, Günter Grass, and Umberto Eco. Meanwhile, Kurt’s son Niko—Alexander’s father—was conscripted after high school into the Reich Labor Service and dispatched to Austria. Subsequently drafted into the army, he was sent first to Brünn (now Brno, in the Czech Republic) and thence through Poland, Galicia, and Ukraine to Dnipropetrovsk, on the Russian front.

In the course of his research, Alexander Wolff learns that his father’s enrollment in the Wehrmacht, rather than the Waffen-SS or the Ordnungspolizei, was no guarantee of his innocence: “The Wehrmacht lent support to every type of Nazi activity in the east.” He observes with evident relief that

on October 13, 1941, when Einsatzgruppe C, Einsatzkommando 5, machine-gunned twelve thousand Jews forced to stand on the lips of pits dug at the southern edge of Dnipropetrovsk, my father was still more than two months from arriving there.

Wolff gleans information about his father’s Wehrmacht service chiefly from Niko’s letters home; the author never discussed this period with his father.

Why did he never go into such things? He wanted to spare us, of course. But the question . . . suggests an answer in the form of another question: How could he have spoken of them? Although that hardly keeps the back half of the refrain from coming round, the companion to He never told me: I never asked.

Alexander’s father and grandfather were reunited in the United States after the war—Kurt helped Niko get into a chemistry graduate program at Princeton, thus enabling his emigration from Germany—but the chasm between their experiences was lasting. As Kurt wrote to Niko’s sister, Maria, “We see through different eyes, because you were on the inside and I was on the outside.” Niko became a chemist, first at DuPont and later with Xerox, and the family settled happily in Rochester, New York. Alexander recalls Niko as a pragmatic, rule-abiding father with a taste for high culture and DIY, who “left his own past unexcavated.” Or, as he puts it more tenderly elsewhere in the book, “With us he was scrupulous about sharing only the beauty.”

Like Sands, Alexander Wolff is keen, after a generation of silence, to follow the untold stories wherever they might lead. He investigates the Merck family tree and its involvement in the Nazi project (Merck provided Hitler with Eukodal, the OxyContin-like opioid to which he was addicted), discovering a great-uncle and shadow-grandfather, Jesko von Puttkamer, whose wife, Annemarie (Elisabeth Merck’s sister), killed herself, and who later became Elisabeth’s consort; as well as an unclaimed half-uncle, Enoch, the son of Kurt and Jesko’s sister, also named Annemarie. In the end, Wolff offers the words of Umberto Eco: “Those things about which we cannot theorize . . . we must narrate.” To bring stories into the light, to render their humanity, is our best hope.

This has always been the impulse of the brilliant playwright who is now the subject of Tom Stoppard: A Life (Knopf, $37.50), by Hermione Lee. Yet Stoppard—who is of the same generation as Niklas Frank and Horst von Wächter—has only latterly become aware of his own story. Born Tomáš Sträussler in Zlín, Czechoslovakia, in 1937, the younger of two sons of Jewish parents, Eugen and Marta, Stoppard was repeatedly saved from disaster by fate. When the Germans invaded, his father, a doctor with the Bata shoe company, was mercifully relocated by his employers to Singapore. The war found them there too, and the family fled to India, again with Bata, but Eugen, who departed after his wife and children, was killed when his ship was bombed at sea. For the next four years, Marta shepherded her small boys around India, moving “six or seven times” before arriving in Darjeeling, where she was courted by a British soldier, Major Ken Stoppard, who called her Bobby. They married, and in 1946, when Tom was eight, returned to the U.K., which became the boys’ home.

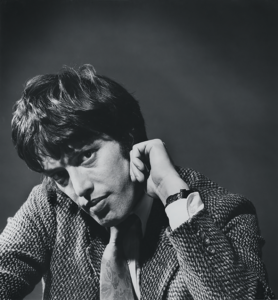

Tom Stoppard © Geoffrey Argent/Art Resource, New York City/National Portrait Gallery, London

Rather like Alexander Wolff’s father, Niko, Bobby long remained quiet about her early life and its terrible losses (her parents, three of her siblings, and many relatives died in the camps). Only in 1993, as a result of Bobby’s correspondence with a great-niece named Sarka Gauglitz, did Stoppard come to understand that he was fully Jewish. He had previously been told that only his father was Jewish: “All these years, Bobby had stayed silent . . . and he and Peter had taken her silence for granted.”

Like Dr. Henry Selwyn in Sebald’s The Emigrants, Stoppard is revealed as someone whose displaced and traumatic childhood was so carefully overlaid by a stable British boarding school education and a successful patriotic life that the trauma might, for a long time, have been thought to have been erased. But the retrospective awareness of that underlying trauma surely illuminates much about Stoppard’s extraordinary and endlessly inventive oeuvre.

Since the overnight success of Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead in 1967, Stoppard has been considered, along with Harold Pinter, one of the two greatest British playwrights of the late twentieth century. His stage plays—among them Jumpers, Travesties, The Real Thing, Hapgood, Arcadia, and the trilogy, The Coast of Utopia—range widely in subject matter, but all are densely layered, theatrically complex, engagingly witty, and intellectually consuming.

The opposite of polemical, Stoppard often presents contrary perspectives and opinions with equal conviction. Lee describes an early spoof documentary, Tom Stoppard Doesn’t Know:

Since Stoppard can’t make his mind up about anything, he puts two of himself on a discussion panel, arguing for and against boycotting (“I find myself in cautious agreement with two opposite views”), for and against theatre as social responsibility. One Stoppard says “his first duty” is to entertain the audience; the other Stoppard (more serious-looking, with glasses) says that any responsible writer has “got to write about society.” Look at Brecht, says the serious Stoppard. The first, more frivolous Stoppard retorts: “Personally I’d rather have written Winnie-the-Pooh than the Collected Works of Brecht.”

Stoppard’s early plays have traditionally been seen as dazzling intellectual games, short on human emotion, and many believe that it was only in his later work, particularly after The Real Thing (1982), a drama about infidelity, that he reached a fuller emotional expression. Lee argues both for and against this narrative as she builds an ever richer, circular understanding of his abiding themes and concerns, of his personal and artistic life, and of his many other passionate engagements—with the plight of Soviet Jewry in the 1980s; the future of the London Library; the Belarus Free Theatre. Always a devoted son to Bobby (though his stepfather Ken was difficult, not to say awful), he was twice married in his youth, the first time unhappily and the second time for twenty years, to the doctor, writer, and television personality Miriam Stoppard, with whom he raised four sons—their own boys Will and Ed, and two, Oliver and Barny, from his first marriage. He then had long relationships with two actresses, Felicity Kendal and Sinéad Cusack, before marrying the television producer Sabrina Guinness in 2014.

He was from the first a glamorous man about town, and screenplays have bankrolled much of that lifestyle; Stoppard maintains that his true passion is for the stage, but Lee is at pains to insist that “he brought to this work the same commitment as he would to a play of his own.” Though he is best known for Empire of the Sun, The Russia House, and Shakespeare in Love, he has also done a great deal of well-paid, often uncredited screenwriting for unexpected features, including Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade, Beethoven, and 102 Dalmatians.

In his newest and perhaps last play, Leopoldstadt—which opened in London in January 2020 and was shut down by the pandemic in March—Stoppard has finally turned his attention to the legacy that his mother hid for so long: the drama follows a family of assimilated Viennese Jews from the turn of the twentieth century to 1955. In the last time frame, we encounter Leonard Chamberlain, a stand-in for Stoppard: “a rather smug, unthinking young Englishman of twenty-five, in Vienna for a literary festival . . . [whose] mother didn’t want him to remember the past, she wanted him to be an assimilated English boy.” In the course of this evening, Chamberlain must confront the fact that

no one is born eight years old. Leonard Chamberlain’s life is Leo Rosenbaum’s life continued. His family is your family. But you live as if without history, as if you throw no shadow behind you.

Lee tells us that “the whole play was written, Stoppard says, in order for this speech to be made.”

Lee’s biography is unusual in that it was commissioned, and published while its subject is still alive. Lee is a highly acclaimed biographer whose rigor and integrity make her decision to write under such conditions surprising. More than once, she records Stoppard’s “dread at the thought of having his letters published or his biography written.” His reasons for asking such an eminent literary biographer to undertake the project make perfect sense. But what made her agree? Surely it was the fact that very few contemporary lives are as rich, as interesting, or as artistically, intellectually, and historically compelling as Stoppard’s.

“Time and again he had talked about his good luck,” Lee notes. “This narrative had become part of his performance. . . . ‘Charm’ . . . does work as a form of defence and a means of persuasion.” Late in life, Stoppard

reproached himself for having trotted out his line so often . . . What was the other side of the story? What of those who did not have the luck, who did not escape the worst of history? . . . He asked himself why he had not thought or written about this, why he had not faced up to it.

Like all of us who live still in the shadow of the Second World War—Niklas Frank, or Philippe Sands, or Alexander Wolff—Stoppard has felt the call to turn and face history.

Lee is frank and thoughtful about the challenges of writing about a living subject. She is aware, as the reader will be, that her interview subjects do not want to speak ill of a friend and colleague who is still among them. In addition to the almost unrelievedly positive portrayal of Stoppard, the seven-hundred-fifty-plus pages of this volume might have been somewhat condensed, were its subject no longer living, thereby rendering the biography easier to wield and to read. In spite of these quibbles, this is an extraordinary record of a vital and evolving artistic life, replete with textured illuminations of the plays and their performances, and shaped by the arc of Stoppard’s exhilarating engagement with the world around him, and of his eventual awakening to his own past.