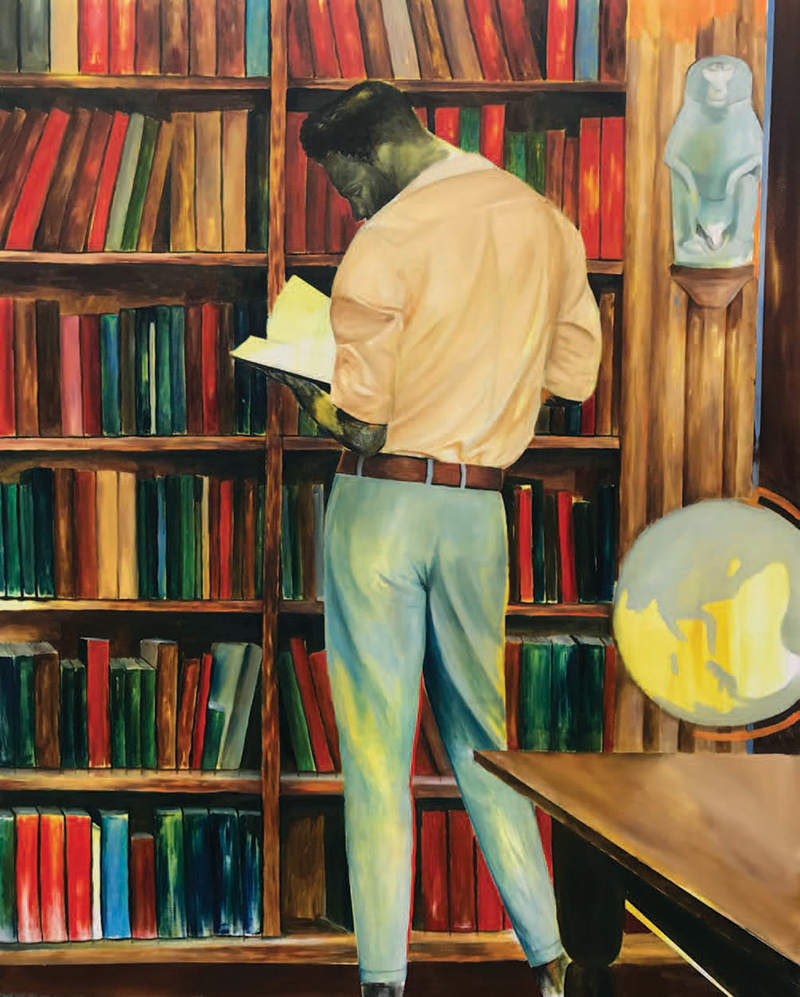

Naître à soi, by Elladj Lincy Deloumeaux © The artist. Courtesy Galerie Cécile Fakhoury, Paris

In The Year of Living Dangerously, the actress Linda Hunt puts on an unforgettable performance as Billy Kwan, a mixed-race, male photojournalist distraught by the poverty and despair in Indonesia in 1965. Repeatedly, with ever greater distress, Kwan cries out, “What then must we do?” A question no less urgent here and now.

Jesse McCarthy’s remarkable book of essays Who Will Pay Reparations on My Soul? (Liveright, $27.95) represents one young black intellectual’s experience grappling with this question over the better part of a decade. The earliest pieces (including the title essay) date from 2014, but most are essentially contemporary, and their cumulative range and force are as exhilarating as they are compelling. McCarthy is an assistant professor of English and of African and African-American studies at Harvard (where I also teach), as well as a lover of rap who grew up in Paris and writes about cafés and music videos. The book’s tone is broadly inviting. As McCarthy notes in his introduction,

These essays are for anyone who wishes to read them, but they are addressed in particular, and very expressly, to the younger generations struggling right now to find their footing in a deeply troubled world.

McCarthy writes with equal authority and scrutiny about trap music and the seventeenth-century Spanish painters Diego Velázquez and Juan de Pareja, the latter a black man and a freed slave of the former. In his brilliant essay “To Make a Poet Black”—originally delivered as a lecture in his Introduction to Black Poetry course—McCarthy brings together Sappho, Kerry James Marshall, Phillis Wheatley, Theodor Adorno, and Ntozake Shange in what feels an entirely organic exploration of the cultural reception of two essential female poets, Sappho and Wheatley.

Classical Sappho was Ethiopian; Christian Sappho is disgusting; the European Enlightenment’s Sappho is noire . . . over the centuries the West has made a decision to favor Socrates over Sappho: his way of knowing over her way, argument over narrative, philosophy over poetry, whiteness over blackness.

Essential to McCarthy’s approach is his belief that “a deep knowledge of the past and critical resistance in the present go hand in hand,” and his insistence on “the need to look backward in order to move forward.” He intends this not in some scolding schoolmasterish way, but rather as a reminder to young readers that “there are no limits to the ideas, realms of knowledge, creative traditions, or political histories that we can lay claim to and incorporate.” The finest essays in this book function like origami, folding together the apparently disparate into a unique and seemingly inevitable form. Some pieces—such as “Notes on Trap”—are as stylistically exuberant as the art they analyze; others are more formally traditional. In sum, they illuminate, almost like a guide for the novice, the rich contemporary cosmos of black American art, literature, and philosophy. McCarthy responds to the work of, among others, Toni Morrison, Kara Walker, Saidiya Hartman, Fred Moten, Ta-Nehisi Coates, Jean-Michel Basquiat, D’Angelo, Colson Whitehead, Claudia Rankine, John Edgar Wideman, and Frank B. Wilderson III.

Wilderson’s Afropessimism comes in for McCarthy’s strongest criticism, although he also disagrees, respectfully, with Coates on the issue of financial reparations. McCarthy’s frustration with both writers lies in their doomed negativity: he believes passionately in possibility, and a revolutionary, almost joyful sense of mission suffuses the book. “Perhaps the black intellectual we still have the most to learn from is David Walker,” he writes in “Language and the Black Intellectual Tradition.” Elements of Walker’s Appeal (1829), McCarthy suggests, inform his interpretation of what the historian Cedric Robinson called the Black Radical Tradition: “America is more our country, than it is the whites’—we have enriched it with our blood and tears.” McCarthy reminds us elsewhere that black Americans are those who have, for years, “fought for the sanctuary of the law,” being “the only population in U.S. history to have known complete lack of lawful protection in regular peacetime society.” He chides Wilderson’s theoretical bleakness and tendency to equate (very real) present harms with slavery, observing quite rightly (and refreshingly unacademically) that

beyond the noise of social media and well outside of academic groves, the black working and middle class has little interest in seminars about the power of whiteness or its fragility. It is looking for tangible, pragmatic answers and solutions.

McCarthy doesn’t mention Edward Said in his book, but the towering figure of late twentieth-century American intellectual life hovers, surely, in the wider pantheon of his thought. Best known for Orientalism (1978), Said was a professor at Columbia whose early work focused on Joseph Conrad; but he became, as McCarthy surely intends to be, a public intellectual and activist, in particular on the question of his native Palestine.

Timothy Brennan, a humanities professor at the University of Minnesota who was a graduate student and close friend of Said’s, has written Places of Mind: A Life of Edward Said (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, $35), which affords a useful and rich explication of Said’s trajectory, from his first mentors—R. P. Blackmur at Princeton and Harry Levin at Harvard—to his affiliation with French theorists, to his firm rejection of their ahistorical, ungrounded approach in favor of a historically informed, pragmatically revolutionary vision—which, indeed, might overlap significantly with McCarthy’s. Though Said was a lifelong citizen of the United States and made his home here for almost fifty years, he was fundamentally an outsider. This agony was made repeatedly clear to him, notably just weeks before his death, when, weak and fatigued by a long battle with leukemia, in a wheelchair at the airport in Faro, Portugal, he was for many hours unable to board his flight home because

his name had tripped a warning, apparently, and they [the airline] demanded he first be cleared by the U.S. embassy in Portugal, which in turn sought approval from Washington, where it was then midnight.

Said was born in Jerusalem in 1935 to a family of wealthy Christian merchants. He was raised primarily in Cairo, where his father, Wadie, had a prospering stationery business. Wadie had American citizenship, which was passed on to his children, and as an adolescent Edward was sent to a prep school in Massachusetts before attending Princeton and Harvard. Handsome and dapper, he lived out the ironies of the privileged cosmopolitan intellectual—at Princeton, “he secretly kept his Alfa Romeo in a garage off campus, using it to escape to nearby campuses in the mostly fruitless search for the company of women”—even as he moved, in the Seventies, “inexorably toward the role not simply of intellectual spokesperson but of active cadre” in the Palestinian movement.

Brennan is very fine on the evolution of Said’s thought and writing, as well as on his return, after his leukemia diagnosis in 1991, to the music that had been central to his youth (he was a pianist of near-concert-level accomplishment) and his creation, with Daniel Barenboim, of the West-Eastern Divan Orchestra. But the book’s professional focus can come at the expense of other aspects of Said’s life. His involvement with the PLO (which culminated in a rupture, after Oslo: “He branded Arafat Israel’s Buthelezi . . . and compared the new Palestinian Authority to the government of Vichy”) is charted but not expanded upon, and readers less familiar with Palestinian politics may founder. Brennan notes Said’s important friendship with his fellow Palestinian-American academic Ibrahim Abu-Lughod, but gives the reader little impression of the man. Similarly, Said’s other friends, his parents, sisters, wives, and children, are present in the text (as is one mistress, a writer named Dominique Eddé, though it’s implied that there were others), but remain largely ciphers. Alas, Brennan is not particularly a storyteller, although happily he does, every so often, include delicious crumbs of humanity, such as Said’s love of Robert Ludlum’s novels, or the elaborate breakfasts he made for his wife, Mariam.

Influential and controversial in equal measure, Said introduced ideas that have since shaped not only literary studies but various interdisciplinary realms. Postcolonial studies, for example, is considered to have arisen out of his work, along with the wide popularization of a particular theoretical vocabulary: “the other,” “hybridity,” “difference,” and “Eurocentrism.” Said himself was skeptical: “I’m not sure if in fact the break between the colonial and post-colonial period is that great. . . . I don’t think the ‘post’ applies at all.” Ultimately, Brennan writes, “He had become the nominal father of a field that he was reluctant to disown but that no longer resonated with his vision.”

A complicated man, Said fell out with many of his peers, surely both because he was intellectually scrupulous and because he was by nature sensitive and choleric. Brennan feels understandably but sometimes rather exhaustingly obliged to defend his former mentor, and to portray him in a positive light. Nevertheless, Said’s vitality and lasting importance as both a scholar and a public figure emerge strongly in these pages. In addition to the seminal texts for which he is best known, much that he said and wrote in his later years also seems prescient, and his passion for humanism resonates particularly now, nearly two decades after his death. He believed it to be

a revolution in learning based on the study of books, especially the forgotten wisdom of the past, and the passion to make knowledge generally accessible. . . . Against the early twenty-first-century world of niche markets, wars of extermination and unrestrained biotechnology, Said argued, only humanism’s strong sense of preserving the past stood as an impediment.

In short, “progressive thinking meant preserving traditions, not destroying them.”

“Avocados and Eggs,” by Daniel Gordon. Courtesy the artist and M+B, Los Angeles

“What then must we do?” is also the question behind the Chilean writer Nona Fernández’s riveting novel The Twilight Zone (Graywolf Press, $16), elegantly translated by Natasha Wimmer. The book, in which the autofictional narrator researches and then imagines crimes from the Pinochet era, “turned Fernández into a household name in Latin American letters” after its publication in 2016, as the cover of this edition notes, and the translation offers an inviting introduction to readers not yet familiar with her work. The terrain that the novel addresses is fertile in part because of its unimaginable brutality. President Salvador Allende’s Popular Unity government was overthrown in September 1973 by a right-wing junta led by General Augusto Pinochet (and aided by the United States). In the subsequent years, tens of thousands of citizens were arrested and many were “disappeared”—tortured and killed, their remains never found.

Fernández, a child at the time, recalls seeing a man’s face on the cover of the magazine Cauce, an image that haunted her: she would come to understand that he was a soldier named Andrés Antonio Valenzuela Morales, who, no longer able to bear the responsibility for his crimes as a government-ordered killer, approached a journalist to tell his story. Twenty-five years later, as a writer for television, she comes across him again, in an interview filmed by her friends:

His face came to life onscreen, the old spell was revived, and for the first time he was in motion. His eyes blinked on camera, his eyebrows shifted a little. I could even see the slight rise and fall of his chest as he breathed.

This impression, of a fixed image from the past that becomes animated, is an abiding metaphor for the novel. To Fernández’s childhood self, the man on the cover of Cauce was no different from episodes of The Twilight Zone:

I’d be lying if I said that I remember the series in detail, but I’m forever marked by that seductive feeling of disquiet and the narrator’s voice inviting viewers into a secret world, a universe unfolding outside the ordinary.

In this case, however, the secret world of which the adult narrator becomes increasingly aware is one of abduction and murder. She recalls her mother telling her about an upsetting experience in the street, when she saw a man throw himself in front of a bus; years later, having researched the incident, Fernández knows who this man was, and the context for his action.

While we were having lunch that day, eating the casserole or stew my grandmother had made, Carlos Contreras Maluje was probably getting beaten in a cell on Calle Dieciocho, a few blocks from my old house.

The novel unfolds as if in layers: the narrator’s present, her memories of childhood, the imagined life of Andrés Antonio Valenzuela Morales, and the stories of the individuals whose lives she researches. Just as Valenzuela—formerly a two-dimensional photograph, imprinted on her memory—comes to life on film, suddenly a living, breathing individual whose actions feel as real to the narrator as her own, so, too, through her careful (but never presumptuous) acts of imagination about the facts that she has gathered, do the lost victims of the era come to life in her novel. Each, like Valenzuela, moves and breathes, though none can escape their fate. Fernández has found an answer to the urgent question: making art is inadequate always, but powerful nonetheless.