“Asthand,” by Nina Röder, from Bath in Brilliant Green, which was published in 2018 by Kehrer Verlag © The artist. Courtesy Galerie Burster, Berlin

A surprising number of novelists are very good; few are extraordinary. Like his compatriot J. M. Coetzee, the South African writer Damon Galgut is of this rare company; like Coetzee, he is stringent, pure. He has, however, and mercifully, a sense of humor, even an occasional playfulness, which leavens that stringency. His new novel, The Promise (Europa Editions, $25), is a narrative framed around Death, or deaths. The Reaper, of course, is no stranger to farce.

Indeed, the novel carries within it the literary spirits of Woolf and Joyce, including, from the former, an almost rushing fluidity of narrative consciousness, and from the latter, a direct allusion to “The Dead” in its final pages, when a torrential rain is unleashed upon the veld: “It falls without judgement on both the living and the dead . . . ” But it is the Faulkner of As I Lay Dying who seems to hover most insistently over the story of the Swart family, which spans three decades from the mid-Eighties onward. Sacred end-of-life rituals and inevitable comedy are interwoven, as the reader attends, over time, the funerals of four of the five Swarts, and comes to know the rich and tempestuous roil of life that precedes their deaths.

Ma—Rachel Swart, née Cohn—is the first to depart, newly dead at the novel’s outset in 1986, ravaged by cancer in her forties, and having returned latterly to the Jewish faith of her childhood. She is mourned, albeit complicatedly, by her husband, Manie Albertus Swart—owner of the Scaly City reptile park and an erstwhile drunken playboy saved by the Dutch Reformed Church—as well as by her three children, Anton, Astrid, and the youngest, thirteen-year-old Amor.

It is through Amor that we enter the novel, and it will be with her that we arrive at its conclusion; but Galgut takes Woolfian liberties with point of view, entering the perspectives of not only his primary characters but their minor counterparts, and even passing individuals and animals, including roving jackals and ghosts. On occasion, the narrator addresses the reader directly: “She dislikes her whole body, as many of you do, but with special adolescent intensity.” He does not, however, enter the thoughts of Salome, the black woman who has cared for the family for years: “She was with Ma when she died, right there next to the bed, though nobody seems to see her, she is apparently invisible. And whatever Salome feels is invisible too.”

Chacal (Jackal), by Rufino Tamayo © 2021 Tamayo Heirs, Mexico/Artists Rights Society, New York City. Courtesy Bonhams

In the first section, Amor—pudgy, pale, struck by lightning as a child—is considered odd; her elder sister, Astrid, meanwhile, a young woman in the bloom of her beauty, is distracted from death as “sex flows through her like a golden wind.” Their brother, Anton, “the firstborn, the only son,” is “anointed, to what he doesn’t know, but the future is his . . . he wants to eat the world.” He must return from military service for his mother’s funeral; on the day before he receives the news, he has for the first time—and perhaps for no reason—shot a woman dead. “My mother is dead, I killed her. I shot and killed her yesterday morning,” he thinks, a Faulknerian conflation (“my mother is a fish”).

His, surely, is the vaunted promise of the novel’s title, soon to be unraveled. Once he inherits his share of the estate (following the second death, Pa’s, from a snakebite, in 1995), Anton spends twenty years supposedly working on a novel, drinking himself into a stupor, only to leave behind, in the end, mere fragments. But the promise lost isn’t Anton’s alone: each of them, in his or her way, has a life distorted or stunted by the bitter legacy of the nation into which they were born. Salome’s son, Lukas, a brilliant student, ends up an angry dropout, doing odd jobs on the property; Astrid, having wangled her way out of an unfortunate first marriage and into the New South African elite, meets an end apt for the tumultuous times soon after Thabo Mbeki’s 2004 inauguration.

Amor is not for nothing named love. Small and fundamentally alone, she turns against the family’s current of destruction from the start. As a child, Amor overhears her mother ask her father to give Salome the title to the house she lives in, and she becomes, enduringly, the family’s conscience. Kindness, selflessness to the point of self-abnegation, material and moral renunciation—a sort of Christlike love that asks nothing in return—would seem, in Galgut’s unflinching yet not utterly hopeless vision, to offer a possible, if flawed, path forward.

To praise the novel in its particulars—for its seriousness; for its balance of formal freedom and elegance; for its humor, its precision, its human truth—seems inadequate and partial. Simply: you must read it. Like other remarkable novels, it is uniquely itself, and greater than the sum of its parts. The Promise evokes, when you reach the final page, a profound interior shift that is all but physical. This, as an experience of art, happens only rarely, and is to be prized.

Whale Bay, Antarctica No. 3, a drawing by Zaria Forman. Courtesy the artist

Jenny Diski, too, writes a lot about death, and a reader is grateful for her humor. Whereas Galgut’s clarity of vision can seem sometimes almost unworldly, Diski is nothing if not parti pris. Everything in her delicious essays is filtered, unabashedly, through her particularly sharp, uncompromising consciousness. The pieces in this volume, Why Didn’t You Just Do What You Were Told? (Bloomsbury, $28), appeared over the course of twenty-five years in the London Review of Books, and were selected by the magazine’s longtime editor, Mary-Kay Wilmers, for this posthumous publication (Diski died of lung cancer in 2016). Whether she is writing about what Henry James called “the distinguished thing” or about celebrities such as Princess Diana or Keith Richards, Diski takes an almost triumphantly dissatisfied, even irascible, approach. Having known (and been very fond of) several Diski-like women in my time, I fell upon this anthology with the delight of familiarity—this also because for many years, when reading the LRB, I would scan for Diski’s byline and turn first to her essays. For those who have not yet had the pleasure, there is the pithiness of her observation and there is the wryness of her prose:

A biography, these days, must be a tale of the unexpected. Wouldn’t modern readers feel cheated to find . . . that Larkin only released his bicycle clips in order to sip cocoa in striped pyjamas and have gently sad, humane thoughts before bed?

Reviewing a memoir by Barbara Taylor titled The Last Asylum, about her experiences in British mental institutions, Diski recounts,

As I read, I saw myself flitting through the pages . . . like a precursor-ghost, or perhaps more a tetchy sprite, engaged in a debate with her text, ticking off the similarities between her experience and mine and weighing up the differences.

She goes on to acknowledge that “this, then, is not even a pretence at a neutral, objective review.”

Diski has a personal history that would make compelling reading even were she not an original stylist, and the most extraordinary essay in this collection, “A Feeling for Ice,” which evolved into the memoir Skating to Antarctica, makes forays into her childhood. Diski’s parents were wildly unreliable, albeit differently so: her adored father was a philanderer and a con man; her mother was mentally unstable. Young Jennifer, as she was then known, lived in several foster homes before ending up back with her loathed mother, from whom she walked away forever after her father’s death. As an adult, Jenny returned to Paramount Court, the apartment building where she grew up, and looked up the mothers of her childhood friends—Mrs. Rosen, Mrs. Levine, and Mrs. Gold—who still lived there. These encounters, along with the revelation of her mother’s fate, are braided together with descriptions of the surreality of the Antarctic vistas, and the unexpected encounters she had there.

As the anthology shows, though, Diski could make almost anything seem interesting. Flaubert once told Louise Colet that he wanted to write “a book about nothing,” and some of Diski’s pieces—on the wondrousness of the office stationery cupboard; on the fizzled career of Dennis Hopper; or on, for heaven’s sake, Piers Morgan’s autobiography—come pretty close to achieving this. One wonders at the brilliant women who deliberately focus largely on fluff: Is it a feminist act, like redeeming embroidery as high art? Or does it stem from a lack of confidence, a sense that a semiserious take on the frivolous is good enough? Diski would doubtless insist that she wrote about what interested her, but her omnipresent irony penetrates all:

I do nothing. I get on with the new novel. Smoke. Drink coffee. Smoke. Write. Stare at ceiling. Smoke. Write. Lie on the sofa. Drink coffee. Write.

It is a kind of heaven. This is what I was made for. It is doing nothing. A fraud is being perpetrated: writing is not work, it’s doing nothing. It’s not a fraud: doing nothing is what I have to do to live. . . . Or: writing is what I have to do to be my melancholy self. And be alone.

Below the Brine, by Elizabeth Schwaiger. Courtesy the artist and Jane Lombard Gallery, New York City

If Diski represents one model for the female ironist, Diane Johnson epitomizes another. Where Diski’s persona—Jewish, neurotic, supposedly indolent—passes all observation through the lens of her complicated self, Johnson, in her fictions, provides instead a briskly witty narrator who, in Waspy, Whartonian style, offers equally delightful and catty observations about all her characters. Lorna Mott Comes Home (Knopf, $28) is Johnson’s first novel in over a decade. She is perhaps best known to readers for her trilogy about Franco-American romantic relations, Le Divorce, Le Mariage, and L’Affaire—the first of which, a National Book Award finalist, was made into a film starring Kate Hudson and Naomi Watts. Lorna Mott, like these earlier books, focuses on the mutual infatuation and bemusement of the French and the Americans, in particular among the chattering classes.

In this case, Lorna Mott is a middle-aged art historian, determined to separate from her philandering second husband, Armand-Loup Dumas, with whom she has spent the past twenty years in Pont-les-Puits, a charming French village not far from Valence. It is also the adopted home of a late expatriate painter named Russell Woods, and a destination for American foodies. Once back in the San Francisco of the late Aughts, Lorna—whose reason for the trip is a lecture in Bakersfield on the Apocalypse Tapestries of the Château d’Angers—finds her native country rather baffling: “She had remembered America differently, without people lying in the street, neighbors being tied up and robbed, junk food, obesity, cars everywhere.” In returning to this unexpected country, she reestablishes contact with her three children from her first marriage, to Randall Mott—Peggy, Curt, and Hams. Or rather, given that Curt has taken off to Thailand after recovering from a near-fatal bike accident, with Peggy and Hams, whose wife, Misty, is “as scary looking as ever, with metal rings hanging out of her eyebrows, and now thinner than Lorna had remembered,” and with Donna, the wife of absent Curt and mother of their twins, a woman whose charms have hitherto been opaque to her mother-in-law. In addition to the immediate concern prompted by these grown children, the reader is also embroiled in the affairs of Peggy’s daughter Julie; of Lorna’s ex-husband Randall and his current, extremely wealthy wife, Amy; of their diabetic, albino daughter, Gilda; of the ubiquitous real estate agent Ursula, whose handsome son Ian attracts the attention of more than one young woman; and of Reverend Train, a college acquaintance who seems now to be courting Lorna. The aftereffects of a flood in Pont-les-Puits; the rising value of the paintings of the late Russell Woods; the activities of a cult-like group called the Circle of Faith; and, chiefly, an unexpected pregnancy all conspire to bring most of these characters together in France.

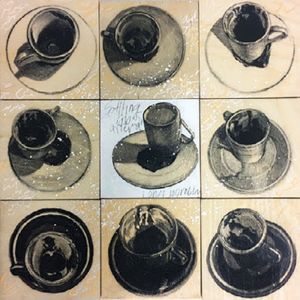

Coffee Cups, Fortune, Floating Composition, by Termeh Yeghiazarian © The artist. Courtesy Tufenkian Fine Arts, Glendale, California

The novel is an engaging confection. It is not, always, the highest version of its form—at times the effervescence of the plot is flattened by emphatic plot-point repetitions, and there are a few loose ends—but it is, at its best, a satisfying example of a time-honored genre. Yet when Lorna Mott reflects, after giving her art history lecture a second time, at the Altar Guild, that “all was over: she was over, the lecture, or at least her own powers of animating this nineteenth-century genre of performance in the twenty-first century, was over,” Johnson is surely also observing that a certain entertaining type of comedy of manners—in which the elegant and amusingly entitled fuss about diminished incomes and inherited legacies or the lack thereof—is also perhaps nearing its end, at least for now, at least here. The frothiness is intrinsic to the novel’s pleasure—while Lorna obviously cares a good deal about how things might turn out, the stakes are, in global terms, fairly low—but this is also what will make it a treat for some, and not at all pleasurable for others. There is nothing, and almost nobody, “worthy” in this novel; clever, dry, and often highly amusing, it is a tender but decided indictment of the United States in the twenty-first century, perhaps best summarized in Lorna’s reflection on her unexpected prudishness at Reverend Train’s advances:

Of course she didn’t believe that “all that” was behind them, didn’t think that life—erotic, artistic, professional—was over for people of any age. . . . Here she thought of Armand-Loup, so robustly sensual, so emphatically rooted in the mire of the physical: sex, cassoulet, a good Bordeaux. Not “mire,” wrong word—but pleasure. Pleasure in the physical. Now with a packet of blue pills, but still with cheerful vigor, even joy. Joy seemed in short supply hereabouts. Was there more joy in France than in America?

Johnson’s answer—keeping in mind that she has resided between Paris and San Francisco for many years, and knows whereof she speaks—would seem a definite “yes.”