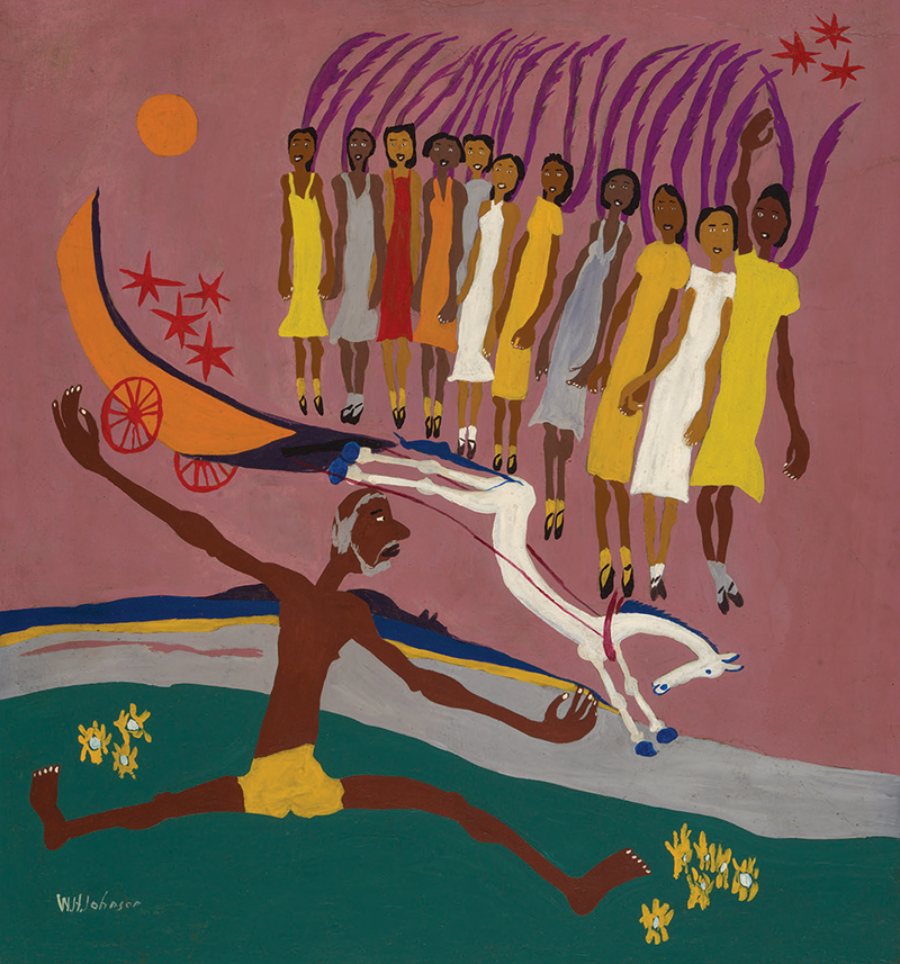

Swing Low, Sweet Chariot, by William H. Johnson. Courtesy the Smithsonian American Art Museum, gift of the Harmon Foundation

Discussed in this essay:

The Black Church: This Is Our Story, This Is Our Song, by Henry Louis Gates Jr. Penguin Press. 304 pages. $30. / PBS. Four hours.

Henry Louis Gates Jr. belongs to the postwar generation that grew up during, and then helped to shape, a shift in black consciousness from a sense of alienation to one of affirmation. When Gates was a student in the late Sixties, HBCUs had long taught Negro history, but the writers of what is sometimes referred to as the first generation of Black Studies brought to campus a new recognition of Africa’s importance to black America, rooted in black nationalist politics. And while movement politics may have fallen off in the Seventies, it left in black people and historians an awareness of their power to control the interpretation of black history. Alex Haley’s popular novel Roots (1976), for instance, in tracing his family back to an ancestor kidnapped from Africa, offered black America its own foundation myth. Similarly, in The Black Family in Slavery and Freedom, 1750–1925 (1976), Herbert G. Gutman argued that, far from being destroyed by the violence of New World slavery, the black family, under the threat of its members being sold away, nevertheless asserted itself, and was often headed by two parents. To be black was not an inherited pathology determined by poverty and racism after all.

This same conviction has marked Gates’s scholarship, which charted new approaches to the writings of the Black Atlantic, the Harlem Renaissance, and works by later black writers who remembered them, particularly Ishmael Reed. His work is also distinguished by its joyous range of reference: Yoruba mythology, Edmund Burke, and Mikhail Bakhtin can lead to one another. Gates is not afraid to claim Isaiah Berlin’s liberal pluralism as an intellectual value. It influences his commitment to multiculturalism. Following the joke attributed to Gandhi, Gates quips that he thinks Western civilization is a pretty good idea. Yet he was not born to be a black neoconservative. His embrace of cultural difference reflects a security of racial upbringing. Gates laughs, in his memoir, Colored People, that he enjoys making uptight black people uncomfortable by being loud in public. Piedmont, West Virginia, was for him what Eatonville, Florida, had been for Zora Neale Hurston—the all-black town where she imbibed the ethos of black folklore that sustained her artistically.

Gates has written about how Frederick Douglass immediately grasped the importance of photography to the cause. So, too, has Gates turned to documentary work. His long association with PBS has resulted in landmark films and television series, usually accompanied by books. Among them are Wonders of the African World (1999); Finding Your Roots (2012); Black America Since MLK: And Still I Rise (2016); and Reconstruction: America After the Civil War (2019). He will give you an advocate to help you and be with you forever, Tallis would have us sing.

To these projects Gates has now added The Black Church, a celebratory documentary and book in which he traces the African encounter with Christianity, and the religion that it became for black people in the New World. This account spans more than four hundred years, from the earliest days of the transatlantic slave trade to the founding of America’s first black denominations to the civil-rights movement and through to the present day. It is a history, as he puts it, that constitutes two stories:

one of a people defining themselves in the presence of a higher power and the other of their journey for freedom and equality in a land where power itself—and even humanity—for so long was (and still is) denied them.

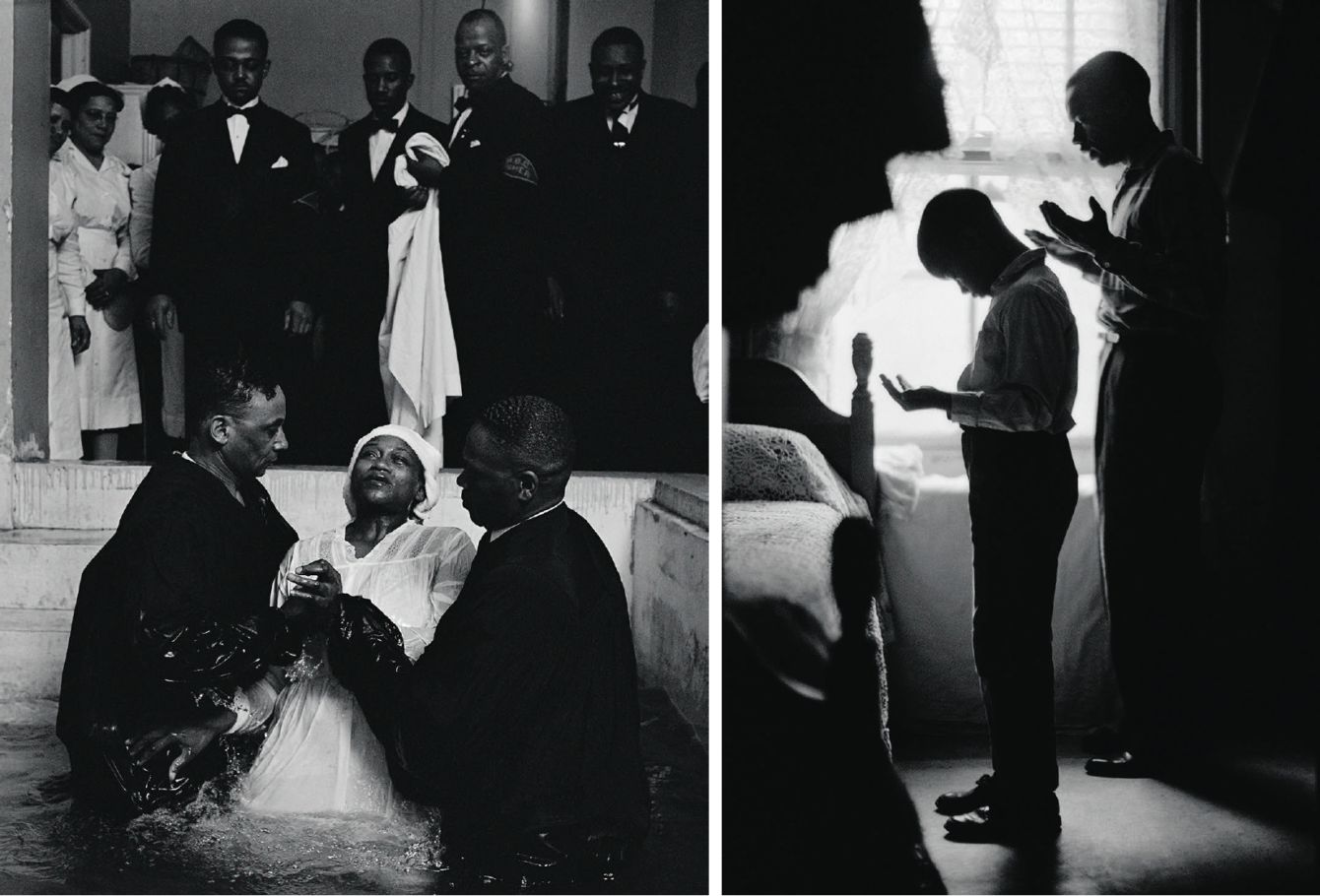

“Baptism, Chicago, Illinois, 1953” and “Daily Prayer, Brooklyn, New York, 1963,” by Gordon Parks. Courtesy and © The Gordon Parks Foundation

“In the Africa of our ancestors,” Gates writes, “the gods had a thousand faces and a thousand names.” The ethnic groups represented in the slave trade brought with them “a marvelously diverse blend of customs, religious faiths, and practices,” all of which they drew on to reshape Christianity “in their own images, to satisfy their own spiritual and practical needs.” One of the long-buried facts of black history, he notes, is how much of the eighteenth-century enslaved population in South Carolina and southern Georgia came from Senegambia and was Muslim. Though there are examples of individuals and communities continuing to practice Islam in some form, it was largely “creolized” with black Christianity. Gates returns to Islam later on, recognizing in the sojourn of Malcolm X a representative quest of many African Americans in the modern era to find alternatives to the Christian church, which they regarded as culpable in the oppression of black people.

“The relationship of the first generations of Africans in North America to the Christian religion varied dramatically in the Spanish colonies and the British colonies,” Gates writes. The Roman Catholic Church welcomed the conversion of the king of Kongo in 1491, and there were confraternities of Africans in Spain as far back as the Middle Ages. The Catholic Church also accompanied Spanish and Portuguese expeditions to South and North America, and Gates points out that enslaved Africans had been living in the Spanish colony of Florida since 1526, and that there is evidence dating from 1594 of black Catholics in the church registers of St. Augustine. In 1693, the Spanish king, hoping to annoy the English, offered sanctuary to fugitive Africans from British territories, provided they converted. But while the Catholic Church may have opposed slavery in official doctrine, this did not stop Catholic countries from leading the way in the slave trade for centuries, or keep the church from becoming the largest slaveholder in America.

Protestants, by contrast, were reluctant to baptize the enslaved, for fear it would inspire them to press for freedom. Direct access to the Word, to read or to know the Bible, the essence of Protestant theology, also raised the humanity-defining matter of literacy. Missionaries thus had to convince slaveholders that Christianity would not encourage the enslaved to rebel, that it could serve as an instrument of docility. To that end, the Society for the Propagation of the Gospel in Foreign Parts was founded in 1701. A white person had to be present at black gatherings to monitor what was being said, but black people still found “surreptitious ways to create sacred spaces in which they could worship God in their own voices and in their own image.” And in spite of all these efforts, Christianity did radicalize some enslaved people, one of whom, in Virginia in 1723, petitioned a bishop for freedom on the grounds that the enslaved were “modern examples of Old Testament Israelites.”

Antiliteracy laws, such as South Carolina’s Negro Act of 1740, made it illegal to teach black people to read, and missionaries avoided biblical teachings that might cause dissent. The act had been passed in response to the Stono Rebellion in South Carolina the year before, led by an enslaved man from the Catholic Kongo. Christianity became racial in order to accommodate slavery. It had been that a Christian could not be enslaved. But the rules changed: a black person could be enslaved, Christian or not. The example of Haiti haunted North America’s white slaveholding population. Denmark Vesey, who was executed on suspicion of having planned an uprising in 1822, had close connections to other free black Christians in Charleston. Nat Turner, who led a rebellion in Virginia in 1831, was a self-taught charismatic preacher inclined to visions.

Until the Great Awakening, the Methodist and Baptist revival that swept the English-speaking Protestant world in the first half of the eighteenth century, most Africans in North America showed little interest in Christianity, Gates says. But the suffering of the carpenter from Nazareth, the story of persecution and redemption, would touch the enslaved imagination. The Great Awakening introduced an ecstatic style of worship to Protestant churches that black people responded to as communal expression. They began to convert to Christianity in large numbers. This shift, scholars say, democratized religion. In the new church, supposedly, white and black got the Holy Spirit together.

The Black Church pays as much attention to how the rites of spiritual renewal evolved as it does to the essential part the black church has played in the social transformation of American life. Religious practice in West Africa was broad, open. In time, hoodoo, obeah, and conjuration were transmuted into black Christian ritual. Gates cites W.E.B. Du Bois:

This church was not at first by any means Christian nor definitely organized; rather it was an adaptation and mingling of heathen rites among the members of each plantation, and roughly designated as Voodooism. Association with the masters, missionary effort and motives of expediency gave these rites an early veneer of Christianity, and after the lapse of many generations the Negro church became Christian.

Oral histories taken down in the Thirties by the Works Progress Administration describe the worship rituals of people who were unable to read but nevertheless memorized passages from the King James Bible, recalling the translation’s original purpose, its “magical poetic diction,” as prayer in the vernacular. The black church created distinct expressions of its own, first in music. Blues, jazz, soul, rock, and even hip-hop “bear the imprint of Black sacred music.” Gates traces the use of drums and the importance of song from the shadowy, underground services of the antebellum South to the anxiety immediately following the Civil War as to what might happen should spirituals—a fusion of African musical styles and evangelical hymns—be performed in public. The story of gospel music is central to the spirit of survival that The Black Church follows, linking the music to the Great Migration, when black people began to leave the South in huge numbers for the relative freedom of cities in the North. The advent of recording influenced the sound of gospel, just as the introduction of the organ and the guitar had earlier. Black music carried the legacy of a world-changing experience.

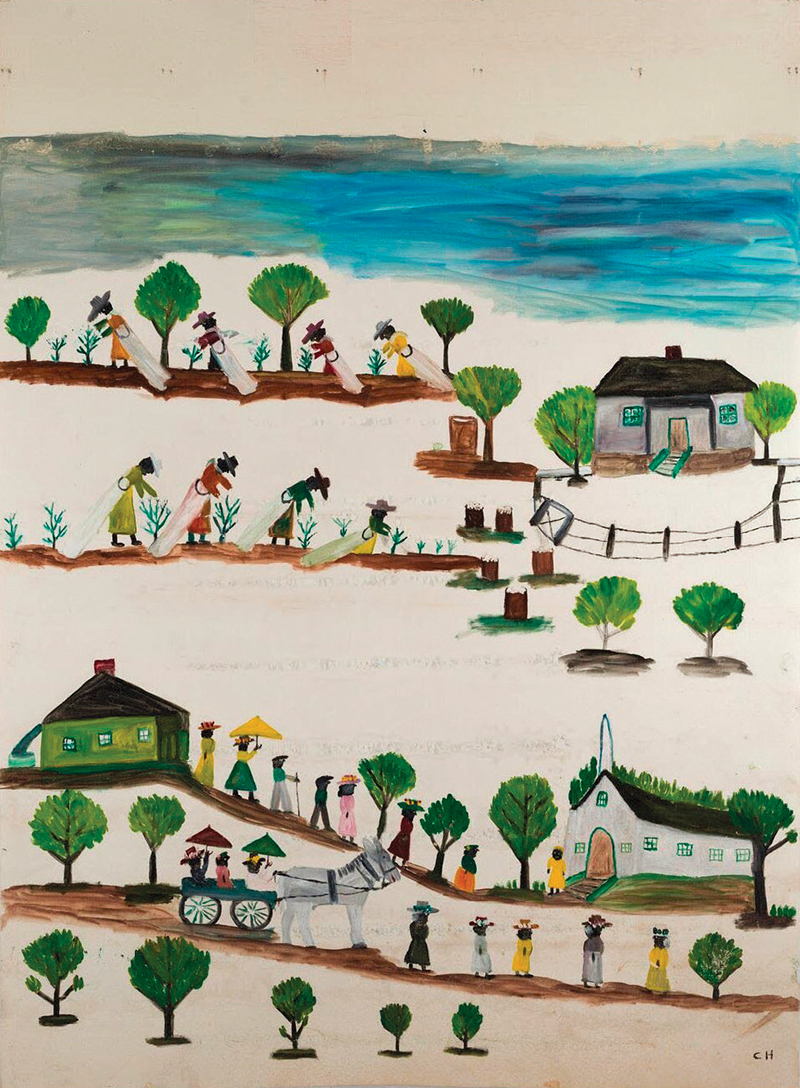

Window Shade, by Clementine Hunter © Cane River Art Corporation, with special thanks to Thomas Whitehead. Courtesy the National Museum of African American History and Culture, gift of the Rand and Dana Jack family

The black church was “the invisible institution.” For a long time, meetings were held in secret, and when they were tolerated, plantation praise houses were the only places of fellowship and gathering in slave society. The first institutions free blacks in the South created on the eve of the American Revolution—albeit always with the required help of whites—were their own churches. Black people were segregated and often abused in mixed congregations, Northern and Southern. In 1792, Richard Allen, who had purchased his freedom, and Absalom Jones, a lay minister, walked out of their white-led church in Philadelphia and founded the African Episcopal Church of St. Thomas, the beginnings of the first black denomination.

Later, white Protestant denominations reckoning with the question of slavery split into Northern and Southern congregations. Abolition was a religious crusade, and the Civil War was God’s furnace of faith. The United States was a Christian nation, and what that meant for black people and white people was not the same, leaving an inheritance of lasting and often bitter difference in philosophy. To make emancipation real, missionary work among freed people led to the founding of a number of schools and colleges affiliated with black churches. After Reconstruction, as black people were driven from political life and once again subjugated in the South, black churches provided the services and aid denied them by government. By the end of the nineteenth century, these houses of worship “shelter[ed] a nation within a nation.” They were anchors for black people in new urban communities created by migration in the early twentieth century, but the transplanting of Southern black culture to the North and Midwest also changed the character of the churches, freeing them of some of the stern parochialism that seemed to go with self-preservation in the embattled South, and proving institutional legitimacy.

Gates makes it clear that there is no single black church, and that black people in the United States are to be found in all faiths, including Judaism, the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, and Bahaism, and that there are a number of black people who do not belong to an organized church or who say that they do not subscribe to a religion. Black Catholics outnumber black Jehovah’s Witnesses, but when we think of the black church, we have in mind Protestantism, specifically seven principal subgroups of the Baptist, Methodist, and Pentecostal denominations. The class differences that emerged in urban black America brought a clash of cultures into the churches, a tension between the decorum of services that respectability politics demanded and the catharsis craved by congregants who adhered to styles of worship marked by African retentions such as shouting, speaking in tongues, getting the spirit, or being laid out under the power of sanctification.

All black churches, large and small, urban and rural, tended to the educational and economic needs of their congregants through forms of social gospel. Adam Clayton Powell Jr. succeeded his father as pastor of the Abyssinian Baptist Church in Harlem, which in the Thirties had a membership numbering in the thousands. Powell became a politician soon after he was ordained in the Thirties, and in 1944 he was elected to Congress, representing his district for twelve terms, until he was voted out amid scandal in 1970. Public service went with his “prophetic ministry,” Gates notes. Apparently, he did not believe in protest. Abyssinian’s current pastor, Calvin O. Butts, explains that Powell believed it hindered his ability to get legislation passed, though he himself had an activist past as an assistant preacher to his father during the Great Depression.

In the mass psychology of freedom fighting, the covenant with God was left to Martin Luther King Jr. to rediscover. It was King’s ministry in Montgomery, and his leadership of the bus boycott in 1954, that ignited the civil-rights movement in the South. That movement was a test of Constitutional principles, and for King it was also a challenge to Christian faith. King told the nation that eleven o’clock on Sunday morning was the most segregated hour in America. But the violence unleashed against the movement—including the 1963 bombing of the Sixteenth Street Baptist Church in Birmingham—made some black churches afraid to engage. By the time of King’s assassination in 1968, nonviolent protest, Christian patience, and legislative reform had been dismissed by Black Power leaders as ineffective. The revolution was going to be secular, or at least not old-time religion.

If King offered the United States the chance to redeem itself, he also recovered the image of the black pastor. Targets of satire in African-American literature in the Thirties, figures of some contempt in the sociology and histories written in the Forties and Fifties, black preachers were personalities—they could enjoy a stardom like that of gospel singers. Aretha Franklin’s father, the Reverend C. L. Franklin, for instance, gave sermons that were released as best-selling records. Some black preachers presided over institutions so large that they were essentially heads of corporations. In the nineteenth century, as acculturation became a central tenet of the missionary intentions of middle-class black churches, expectations for black ministers were sharply defined, specifically with respect to education. The ministry became one of the few professions in which black men could rise unencumbered.

Martin Luther King Jr. is a reminder that genius does not come like apostolic succession, but rather strikes like sainthood. Black leaders who followed King had to contend with his legacy, and it was the Reverend Jesse Jackson in his 1984 and 1988 presidential campaigns who eventually bridged movement politics and traditional electoral politics. In the immediate aftermath of King’s death, however, when black America seemed to be debating which road to take, James H. Cone published Black Theology and Black Power (1969) and A Black Theology of Liberation (1970), reinterpreting Christianity through a black nationalist lens. King’s call for justice for the poor never lost its urgency or dignity as a political objective. But his notion that blackness represented the universality of the human condition found less resonance. Cone argued that black religion is freed, not confined, by historical context. The cross had become detached from a sense of ongoing suffering, and had been turned into an ornament. Theology that did not address the religious meaning of the African-American experience was, to him, bankrupt. In Cone’s view, white supremacy was the negation of American Christian identity.

Throughout The Black Church, Gates is talking about the institution at its best, so to speak. It is both Cone’s church and King’s, as much Jeremiah Wright’s and Cornel West’s as John Lewis’s and Raphael Warnock’s. But Gates does not neglect the long history of women in the black church. Though unacknowledged in many congregations, women were the essential, the foundation, yet they had to fight for decades to be heard, to be ordained, to create a body of womanist theology. Similarly, Gates considers the history of the LGBTQ community. Strict morality in the black church, as elsewhere in Christianity, was acted out on the body, the breeding ground of sin. The legendary choir impresario Reverend James Cleveland may have had to remain in the closet, but in the black church the LGBTQ community has now won at least some space for its members of faith. LGBTQ rights, along with women’s reproductive health and family planning decisions, nevertheless remain, as Gates puts it, “highly contentious in the Black Church, as it does in the larger Black community.”

Black churches continue to be divided on many social questions, reflecting the country as a whole. But The Black Church is clear that the tradition it celebrates is liberation theology.

The church fueled slave rebellions, nurtured and sustained the Underground Railroad, and was the training ground for the orators of the abolitionist movement. . . . It powered antilynching campaigns and economic boycotts, and formed the backbone of and the meeting place for the civil rights movement. Rooted in the fundamental belief in equality between Black and white, human dignity, earthly and heavenly freedom, and sisterly and brotherly love, the Black Church and the religion practiced within its embrace acted as the engine driving social transformation in America, from the antebellum abolitionist movement through the various phases of the fight against Jim Crow, and now, in our current century, to Black Lives Matter.

This did not feel true during the protests in Ferguson, Missouri, in 2014. If anything, the generational gap seemed expressed as rejection of the church, as had happened back in the Sixties, and in spite of the presence of black clergy among the protesters. Then came the 2015 shooting of eight black parishioners and their minister in Mother Emanuel AME Church in Charleston, South Carolina. The black church was back on the front line. In communities across the country, black churches have shown themselves to be valuable partners in coalitions where they themselves have leaders committed to social change. Yet rather than churches inspiring the movement, the movement has given black churches a renewed sense of purpose and connection. This fits another historical pattern: black churches have sometimes had to catch up with their congregations. Black people moved to Harlem first, then their churches followed.

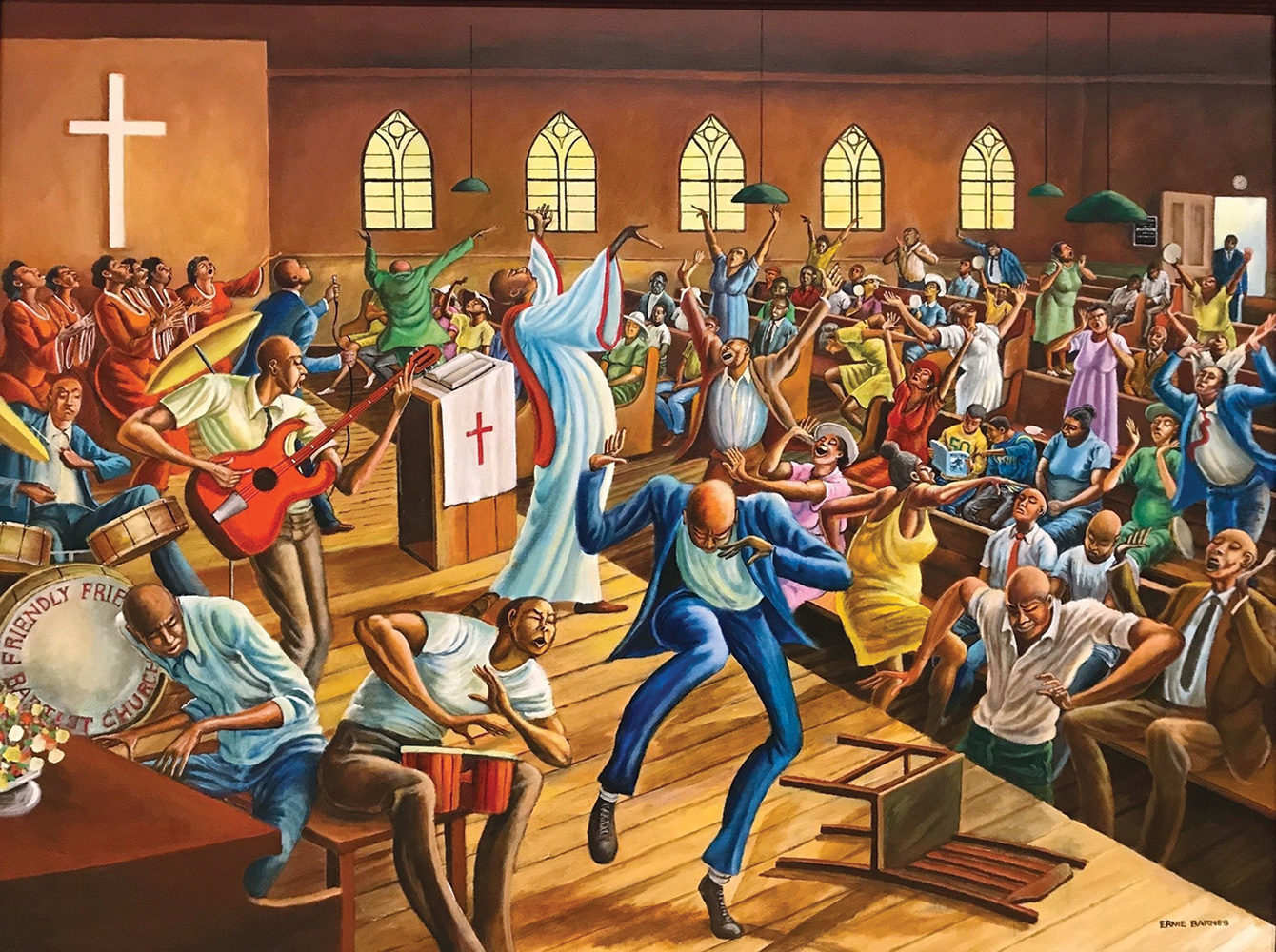

Friendly Friendship Baptist Church, by Ernie Barnes © Ernie Barnes Family Trust

The Black Church is a history of two tendencies within the institution—high and low, they could be called. Martin Luther King Jr. perhaps reconciled them in the ideals that moved him and in how splendidly he could summon a multitude to defend them. As such, The Black Church takes all black religious expression seriously, from the storefront evangelicalism and cult leaders of the migration to the Reagan-era prosperity ministries that were the forerunners of today’s independent megachurches.

Gates’s study is what he might call double-voiced. He includes illuminating interviews with distinguished historians, theologians, ministers, and gospel singers, talking about various black pioneers in America’s religious culture. The text itself has a call-and-response quality reminiscent of a black service, the past being answered by the present. Gates presents his ideas in dialogue with Du Bois and The Souls of Black Folk. For Du Bois, the presence of God and the Holy Ghost were made manifest in “the Frenzy,” one of three elements, including the preacher and music, that he observed were the most important characteristics of black religion:

The Frenzy of “Shouting,” when the Spirit of the Lord passed by, and, seizing the devotee, made him mad with supernatural joy, was the last essential of Negro religion and the one more devoutly believed in than all the rest. It varied in expression from the silent rapt countenance or the low murmur and moan to the mad abandon of physical fervor,—the stamping, shrieking, and shouting, the rushing to and fro and wild waving of arms, the weeping and laughing, the vision and the trance. All this is nothing new in the world, but old as religion, as Delphi and Endor. And so firm a hold did it have on the Negro, that many generations firmly believed that without this visible manifestation of the God there could be no true communion with the Invisible.

Gates says in Colored People that he feared the power in the sanctified church. In a very personal epilogue to The Black Church, he recalls how when he was twelve years old he silently promised God that if his mother recovered from her severe illness he would dedicate his life to Christ. She did, indeed, get better: “Uh-oh. I had made a deal with Jesus.” For two years, Gates was a terrified and abstinent teen, until he migrated into the less strenuous atmosphere of his father’s Episcopal church. He was saved, but he never underwent the deeply emotional conversion that was meant to accompany getting the spirit. He was relieved not to have surrendered himself.

Gates notes that Du Bois intuited the importance of the backcountry black church even though it was far from his own staid New England experience. Like Du Bois, Gates preferred to watch the black church from the sidelines. Making the PBS documentary, however, has revealed to him the “meaning and magic of the Black Church.” It is, he declares, “Black culture’s site of the beautiful and the sublime.” During the civil-rights movement, liberation in the sense of Christian salvation was understood as a metaphor. Black aspirations were stated in secular terms, addressed to the secular state. Gates wants to credit the many thousands gone, their tongues of fire, the black and unknown bards of James Weldon Johnson’s sonnet, and in so doing, contradict Du Bois’s assertion that the Talented Tenth, a black elite, will lead the masses. So that you will not die.