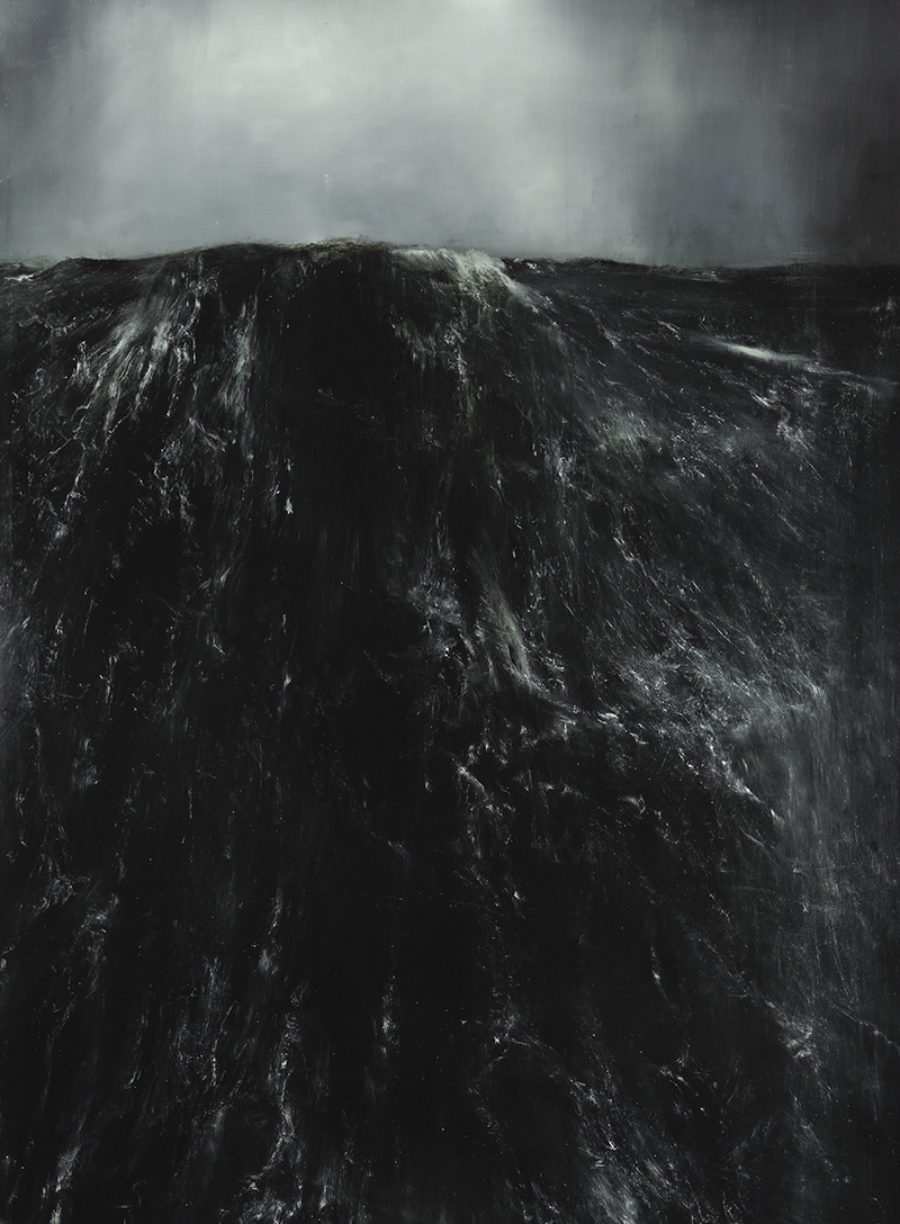

MER HAUTE (detail), by Thierry De Cordier. Courtesy the artist and Xavier Hufkens, Brussels

Two summers ago, I found myself on a whale-watching journey in Provincetown, Massachusetts, where I was teaching at the Fine Arts Work Center. We swayed from one side of the ship to the other to observe various species—fins, minkes, and humpbacks—performing synchronized acrobatics in waters where fishing nets threaten. Tranquil, playful, spouting fountains of ocean spray and then plunging under, they seemed not at all the wicked beasts that history had taught us to fear. I recalled that we were in the same seas in which Moby-Dick’s Pequod had sailed, and I thought this might have been—however unconsciously—why I had signed up for the adventure. It was as if the whales were calling me back to a promise I had made to myself long ago.

Years earlier, I’d had a life-changing encounter with Edwin Shneidman, a renowned psychologist and the co-director of the Los Angeles Suicide Prevention Center. At the time, I was in the painstaking early stages of work on a book about my youngest sister’s suicide, and I’d flown to Los Angeles to interview Shneidman with hopes that he might be able to tell me more about the suicidal mind. Shneidman had developed a procedure called the “psychological autopsy,” a set of interviews with surviving relatives, friends, and acquaintances of a person who has died under mysterious circumstances, which is designed to classify the likelihood that a subject committed suicide. He’d coined the term “suicidology” to describe his work.

What I hadn’t known when I set out was that Shneidman was also a devotee of literature. He’d dedicated an entire room of his L.A. ranch house to paraphernalia related to Herman Melville and Moby-Dick. Among the fascinating documents, books, and papers we discussed during my visit was a concordance he had compiled about the relationship of Melville’s great novel to mental distress and death. When he learned that I was a poet and novelist, he encouraged me to reread the novel—of course, as an English major, I had “read” it, surfing over exhaustive chapters about whaling history and cetology, in a course on American literature—with this relationship in mind.

My days with Shneidman were fevered by my desire to understand my sister’s death. His theory about Melville fascinated me, but it didn’t seem immediately relevant to my quest, and so I put off rereading the text. I was still working on my book when Shneidman died in 2009, and we never had the chance to return to Melville. I might have taken up the question myself, but after ten years of writing, researching, and finally publishing History of a Suicide, I thought I had finished with this dark subject.

I was wrong. A year after my encounter with the whales off Provincetown, I was quarantining on the East End of Long Island, another old whaler’s way station. As the weeks and then months of isolation piled up, the whales beckoned. Perhaps it had to do with losing my mother in late March—one loss brings back another, memories long forgotten rush forth, questions and inner quarrels arise—but I knew that now was the time. I took out the dog-eared copy of Moby-Dick I’d sifted through when working on my memoir, and I set out to read the novel through the lens of self-destruction.

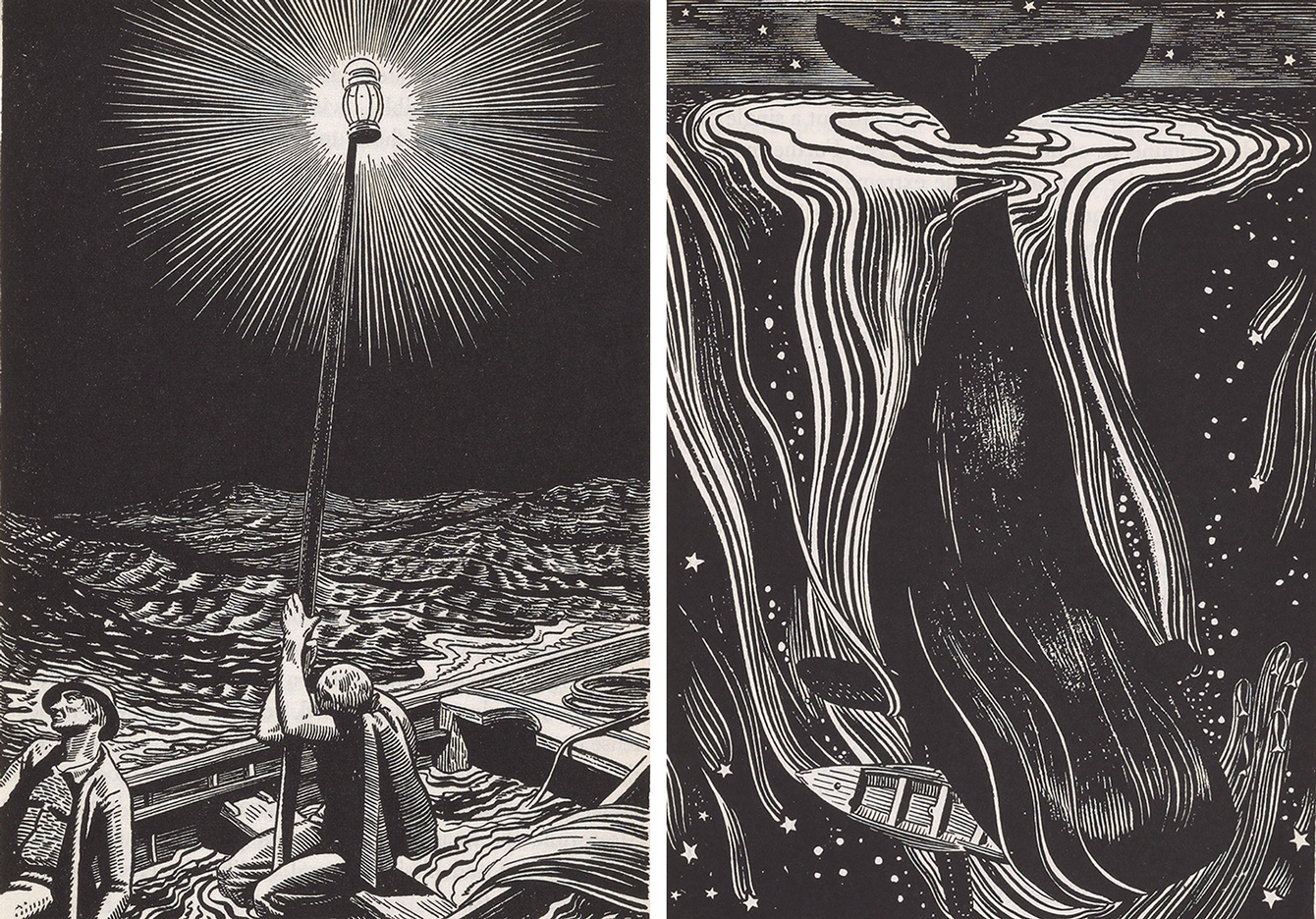

Over the next few months, I read and listened to an audio version of Moby-Dick, sometimes alternating between mediums. I liked the orderly arrangement of the book’s 135 chapters, an inventory of the ship itself, many beginning with the definite article: “The Mast-Head,” “The Cabin-Table,” “The Quarter-Deck · Ahab and All,” “The Chart,” etc. I paged through Matt Kish’s Moby-Dick in Pictures, in which each page of the novel inspires an illustration. I worked through several biographies, including Andrew Delbanco’s Melville: His World and Work, Elizabeth Hardwick’s Herman Melville, and Michael Shelden’s Melville in Love; reread my favorite Melville story, “Bartleby, the Scrivener,” and his masterful last work of fiction, Billy Budd; and listened to the audiobook of Nathaniel Philbrick’s In the Heart of the Sea, about the real-life calamity that inspired Moby-Dick, fascinated by its descriptions of mercurial whales and dirty, hungry whalers abandoning their families for years on end in a quest that left many dead and penniless.

But why this great late interest? Why was I once again chasing the elusive whale? It was as if, like Ishmael—an exile wandering at sea, Melville’s narrator and conscience—I was compelled forward by

the invisible police officer of the Fates, who has constant surveillance of me, and secretly dogs me, and influences me in some unaccountable way—he can better answer than any one else. And, doubtless, my going on this whaling voyage formed part of the grand programme of Providence that was drawn up a long time ago.

Moby-Dick is many things—a tale about whaling, race, and history; a philosophical treatise; a psychological investigation; a Shakespearean tragedy; and an adventure story, at once terrifying and profound. But it is also a novel about self-destruction and the quixotic nature of the human mind. The plot of Moby-Dick, of course, follows Captain Ahab, set on revenge against an albino sperm whale that had destroyed his ship on a previous voyage, maimed him almost to death, and took “the old captain’s manhood,” as Elizabeth Hardwick puts it. At the book’s close, poor Ahab drowns in the sea, “caught and twisted” by his own harpoon line and dragged by the diving whale. To his great friend Nathaniel Hawthorne—to whom he dedicated the book and for whom, some have speculated, he may have possessed unreturned sexual desires—Melville called it a book “broiled” in “hell-fire.”

While I read, I thought often about the darkness and desperation of Ahab’s quest, but also about Melville’s own tormented mind and the unsettling, erratic voyage he took toward the novel’s completion. Melville had firsthand knowledge of whaling and sea journeying, having spent his early years at sea as a cabin boy and whaler, but what gives the novel its force and raging undercurrent—its “howling infinite,” as he described the sea—is the rhapsodic, manic pulse of his narration. One cannot compose an urgent novel of retribution and monomania, formally risky (for its time), enigmatic, penetrating, rich with history and etymology, metaphysical, mesmerizing in its lyric density, without living life to its very precipice.

“He had pretty much made up his mind to be annihilated,” Hawthorne wrote of Melville,

but still he does not seem to rest in that anticipation and I think, will never rest until he gets hold of a definite belief. . . . He can neither believe, nor be comfortable in his unbelief; and he is too honest and courageous not to try to do one or the other.

The novel trembles with this undercurrent, bellows with bold grandiosity, radiating fear, awe, bewilderment. There is the unforgettable, unforgivable, haunting image of poor young Pip, “tender-hearted” and “bright,” adrift at sea, bobbing his head, “the intense concentration of self in the midst of such a heartless immensity,” and once rescued, his mind is forever transformed into a state of brilliant madness, an apt metaphor for the genius of the novel itself.

Illustrations by Rockwell Kent from a 1930 edition of Herman Melville’s Moby-Dick. Courtesy Yale University Library, New Haven, Connecticut

Melville wrote Moby-Dick in the upstairs study of a farmhouse in the Berkshires that he called Arrowhead. With him in the small house were his wife and son, his sisters, and his mother, but Melville mostly remained isolated, submerged in his study writing the great novel, having his meals brought up to him by his wife. Jill Lepore writes that he kept a lock on the door and a harpoon nearby, which he used as a fireplace poker.

The novel, like a long hybrid poem, is an ars poetica, a book about writing as much as it is a book about the sea. Ahab tells Starbuck of his history—“forty years on the pitiless sea!”—and questions the sanity and futility of his quest. He is like the weary writer, with no knowledge of whether the book will come together, whether all the years of work, the “pushing and crowding, and jamming myself on all the time,” will amount to anything equivalent to the energy mustered in its creation.

Shelden has proposed that the novel’s psychic energy was propelled by Melville’s adulterous passion for Sarah Ann Morewood, with whom Melville was allegedly having an affair while he wrote the book. Morewood was a poet, a woman of literature and the arts, bookish, unconventional, a flirt, the wife of a successful businessman, and a host of elaborate parties. When Melville met her, in 1850, he was unhappily married to the plain and unartistic Elizabeth Shaw, known as Lizzie, the daughter of the chief justice of the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court, who repeatedly helped Melville out of his mounting debts, and whom Melville respected and admired. Shelden claims that Melville was so besotted with Sarah that he persuaded his family to move from New York to the Berkshires, where she lived in a mansion independent of her husband. He borrowed money to buy Arrowhead, which adjoined the Morewood estate. He completed Moby-Dick around a year after his first meeting with Sarah. Shelden speculates that Melville fueled Ahab’s quest with his own subverted erotic passion and madness. Others claim that he was motivated by his unrequited feelings for Hawthorne. In any case, paramount in Melville’s mind was the need to make Moby-Dick a financial and critical hit: he was in debt and quickly fading from the limelight after his early success as a writer of popular seafaring yarns.

Fear of poverty, secret desire, ambition, adultery, a mind unable to seek comfort—was that impulse, like Ahab’s, suicidal? Or did writing save Melville from self-destruction? He struggled throughout his life with mental illness. (“Heaven have mercy on us all—Presbyterians and Pagans alike,” Ishmael declares in one of the book’s more amusing lines, “for we are all somehow dreadfully cracked about the head, and sadly need mending.”) Lepore notes that Melville’s father died “raving mad,” and that “Herman watched him lose his mind.” During the years Melville was writing Moby-Dick, Hardwick adds, Lizzie “thought him deranged and considered a separation.” Delbanco writes that Lizzie’s brother felt he needed to rescue her from Melville. But she chose to stay, and in a letter promises to “pray for submission and faith.” He drank and at times exhibited violent behavior. He wrote his friend Evert Duyckinck that “in all of us lodges the same fuel to light the same fire. And he who has never felt, momentarily, what madness is has but a mouthful of brains.” Of his diabolical novel, once publication was imminent, he warned Sarah:

Don’t you buy it—don’t you read it, when it does come out, because it is by no means the sort of book for you. It is not a piece of fine feminine Spitalfields silk—but is of the horrible texture of a fabric that should be woven of ships’ cables & hausers. A Polar wind blows through it, & birds of prey hover over it.

The finished novel, “a wicked book,” he said to Hawthorne, was a sort of corpse kept alive by its creation.

Moby-Dick is death-obsessed. The ship is black, like a hearse, a “cannibal of a craft, tricking herself forth in the chased bones of her enemies.” The fires used to melt whale blubber at night turn the Pequod into a “red hell.” Whales are described as “phantoms.” The restless sea, a metaphor for Ahab’s desperate melancholy and desire for revenge. But revenge against what? For Melville, the despair of living? Climbing debts? Marriage to a wife who did not satisfy him? Fear of failure? Yet he persisted in the pursuit.

Listen to the novel’s grand opening, in which Ishmael announces that the voyage—or for Melville, writing—is a way of staving off depression:

Whenever I find myself growing grim about the mouth; whenever it is a damp, drizzly November in my soul; whenever I find myself involuntarily pausing before coffin warehouses, and bringing up the rear of every funeral I meet; and especially whenever my hypos get such an upper hand of me, that it requires a strong moral principle to prevent me from deliberately stepping into the street, and methodically knocking people’s hats off—then, I account it high time to get to sea as soon as I can. This is my substitute for pistol and ball.

In an early chapter, “The Sermon,” Ishmael attends chapel before going off to sea. The Book of Jonah is preached, foreshadowing the journey and announcing the novel’s biblical undertones. Ishmael’s hope is that the adventure might cure him of melancholy and his suicidal impulses. Indeed, his awe of the sea and of the whale, from its organs to its teeth, and his infatuation with the savage, quixotic aspects of his homoerotic friendship with Queequeg keep him aloft.

For Ishmael, an orphan, one of the “broken-hearted” who cannot find love and acceptance on land, the whaling adventure is a way of fending off death for those to whom death seems “the only desirable sequel”:

Death is only a launching, not the region of the strange Untried; it is but the first salutation to the possibilities of the immense Remote, the Wild, the Watery, the Unshored; therefore to the death-longing eyes of such men, who still have left in some interior compunctions against suicide, does the all contributed and all receptive ocean alluringly spread forth his whole plain of unimaginable, taking terrors and wonderful, new-life, adventures; and from the hearts of infinite Pacifics, the thousand mermaids sing to them—“come hither, broken-hearted; here is another life without the guilt of the intermediate death; here are wonders supernatural, without dying from them. Come hither!”

But for Ahab, there is no comfort in the voyage. Peleg, one of the owners of the Pequod, says of the captain and his maimed leg:

He ain’t sick; but no, he isn’t well either. . . . He’s a queer man, Captain Ahab—so some think—but a good one. Oh, thou’lt like him well enough; no fear, no fear. He’s a grand, ungodly godlike man, Captain Ahab; doesn’t speak much, but when he does speak, then you may well listen . . . I know he was never very jolly; and I know that on the passage home, he was a little out of his mind for a spell; but it was the sharp, shooting pains in his bleeding stump that brought that about, as anyone might see. I know, too, that ever since he lost his leg last voyage by that accursed whale, he’s been a kind of moody—desperate moody, and savage sometimes.

Ishmael and Ahab represent two sides of Melville’s self at war with each other: Ishmael, a believer and survivor, and Ahab, who has lost all belief and is lured toward destruction. One of the most telling (and most masterful) chapters, “The Quarter-Deck,” describes Ahab’s traumatic psychological state. Starbuck says that Ahab’s “vengeance on a dumb brute” is “blasphemous.” Ahab responds:

Hark ye yet again—the little lower layer. All visible objects, man, are but as pasteboard masks. But in each event—in the living act, the undoubted deed—there, some unknown but still reasoning thing puts forth the mouldings of its features from behind the unreasoning mask. If man will strike, strike through the mask! How can the prisoner reach outside except by thrusting through the wall? To me, the white whale is that wall, shoved near to me. Sometimes I think there’s naught beyond. But ’tis enough. He tasks me; he heaps me; I see in him outrageous strength, with an inscrutable malice sinewing it. That inscrutable thing is chiefly what I hate; and be the white whale agent, or be the white whale principal, I will wreak that hate upon him. Talk not to me of blasphemy, man; I’d strike the sun if it insulted me.

Self-hate, trauma, isolation, an inability to break free, as if the mind is continually chasing itself—these are the characteristics that threaten Ahab and that finally lead to his demise. And these, too, are attributes of the suicidal mind.

In 1867, sixteen years after the publication of Moby-Dick, Melville’s son Malcolm shot himself in the head with a pistol—the very fate Ishmael set out to escape. Before revisiting the story with Shneidman’s framework in mind, I knew that Malcolm had committed suicide, but I had thought that it was surely after this death that Melville had written his great novel, that his work had been fueled by a need to understand his son’s act. But I had gotten the timeline wrong. Malcolm was two years old when the novel was published. This information brought a new thought, one that Shneidman had perhaps hinted at many years ago. Research has shown that there is a genetic basis for suicide, that it tends to run in families, but perhaps there was more at work; perhaps the suicidal child unconsciously becomes the recipient of a parent’s self-hate, melancholy, anger, and subverted hopelessness. One can imagine the atmosphere in the house Malcolm grew up in, where the mad genius everyone in the family catered to loomed in the attic overhead.

At a meeting of the Melville Society on December 28, 1975, Shneidman presented a paper titled “Some Psychological Reflections on the Death of Malcolm Melville.” He and his colleagues had performed a pseudo-psychological autopsy on Malcolm at the Suicide Prevention Center in 1973. They conducted it as if it were an open case, and concluded that Malcolm’s death was not an accident. Here is Shneidman’s thesis:

In this paper, the assertion is made that Herman Melville himself had been a psychologically “battered child” and, in a way typical for battered children, psychologically battered his own children when it came his turn to be a parent. The further assertion is made that for Malcolm, his father was suicidogenic; and established this penchant in Malcolm (through his neglect, active rejection, fearsomeness, and his fixed attention to his own writing—Redburn, White-Jacket, and Moby-Dick) within the first two years of Malcolm’s life. For Malcolm, the psychological basis of his suicidal state was isolated desperation—a ubiquitous characteristic of most suicides. Malcolm had a deep unconscious feeling of not being wanted by his father; that it would be better if he were out of the way, dead. On the morning of his death, the choice for Malcolm was between the memory of his mother’s kiss a few hours before and the terror of (and the need to protect himself against) his father’s rage to come.

Shneidman concludes that Melville perpetuated his unconscious reactions to his childhood—his father’s mad rage—in his own household, and that the message was that “Malcolm should not get in the way, should not grow up, should not live out his own life.”

Delbanco claims that as the Melvilles’ marriage fell apart, Malcolm, an eighteen-year-old who was gentle and truthful, suffered greatly. He had volunteered for the state militia, where he wore a uniform and carried a pistol, meeting for drills and calisthenics in the evening—a puffed-up soldier without a war to fight. He often went out late and came home drunk and met with his father’s disapproval. Herman’s family indulged his artistic endeavors and genius. His wife and sister were often his scribes. Malcolm, the firstborn, must have seen his father as someone he could never live up to.

On the night before Malcolm died, he stayed out until three in the morning after an evening that had begun with military drills. “His mother, unable to sleep, had stayed up waiting for him,” Delbanco writes. “The next morning, Malcolm did not appear downstairs or report to his job in Richard Lathers’s law office.” Herman told Lizzie to let him sleep and pay the consequences at work. After returning home that evening, Melville broke down the door and found his son dead.

Melville was haunted. He was falling apart. By the time he finished writing Pierre, Moby-Dick had failed. But in spite of its failure, Melville pushed forward. From all indications, his wasn’t a happy life. It was one of alienation, occasional bursts of friendship, lovelessness. None of his books made money. He stopped writing novels and turned instead to poetry, and in his later years became a customs inspector. Then, in the last years of his life, he worked at the unfinished novella Billy Budd, his second masterpiece, after Moby-Dick. Many have concluded that it was written as a way of seeking absolution and release from the guilt and grief Melville felt after Malcolm’s death.

The story concerns an innocent, handsome young sailor, Billy, called “Baby Budd” because of his “lingering, adolescent feminine face,” loved by all who knew him. He is unjustly accused of mutiny by Claggart, the paranoid, villainous, jealous master-at-arms of the ship. Captain Vere, kind, noble, known as “Starry Vere” for his ponderous nature, is fond of Billy, and calls him a “king’s bargain” when he joins the ship. Vere presents the mutiny charges and asks Billy to respond. Roiled in anger, disbelief, and shock, and known for having a speech impediment, Billy is silent. Vere, “so fatherly in tone,” tells him to take his time, “doubtless touching Billy’s heart to the quick,” and Billy impulsively clocks Claggart, who falls and dies. Vere—“a man old enough to have been Billy’s father”—knows Billy is innocent: “I believe you my man,” he tells him. And yet belief is not enough to save Billy. In wartime, if a man strikes his superior, it is considered a capital crime. Vere says:

But for us here, acting not as casuists or moralists, it is a case practical, and under martial law practically to be dealt with. . . . Well, the heart here, sometimes the feminine in man, is as that piteous woman, and hard though it be, she must here be ruled out.

After telling Billy his regretful fate like a helpless father, knowing his son is in danger but unable to intercede, Vere solemnly kisses Billy on the cheek—not an impulse one expects of a captain.

Billy, as if out of Melville’s emotional urgency and desire for redemption, absolves Vere as a son would absolve a loving father. Billy’s last words are:

“God bless Captain Vere!” Syllables so unanticipated coming from one with the ignominious hemp about his neck . . . syllables too delivered in the clear melody of a singing bird on the point of launching from the twig—had a phenomenal effect, not unenhanced by the rare personal beauty of the young sailor, spiritualized now through late experiences so poignantly profound.

Years later, after Billy’s hanging, Captain Vere is on his deathbed, in a drug-induced stupor, and murmurs mournfully, “Billy Budd, Billy Budd,” never having forgotten the boy’s tragic and unnecessary end, his life just beginning.

Who can understand the reasons behind self-murder? Melville was a complicated, elusive genius, and perhaps it is unfair to read his novels as veiled biography. Perhaps too, unfair to blame his son’s suicide on his father’s obvious neglect and rage, and as immortalized in Billy Budd, his deep regret and grief. But isn’t it through poetry and fiction that we glimpse flickers of the inner world, something psychology textbooks can’t show us? What Moby-Dick lays bare is that the torments of the soul are real and possibly fatal—that suicide exists between the desire for self-destruction and salvation, between death and survival.

Shneidman knew that a suicidal impulse differs from depression, that it is fueled by trauma—Ahab’s leg and the cost to his manhood—and that trauma brings isolation, a mind in painful fervor, and an unfathomable desire to end the pain. If Melville is Ishmael, ironically, he is the only one of the Pequod’s crew who survives, saved by staying afloat in the coffin turned lifeboat originally made for Queequeg.

I’ll let Melville, in the voice of Ishmael, have the last word. Ishmael reflects that there are moments when the sea is calm and one can feel a dreamy repose, a sense of being part of the universe in “one seamless whole.” But for Ahab, those moments proved “tarnishing.” In a poetically intense, darkly beautiful passage about man’s internal struggle between the ever-shifting dualities of self-destruction and the will to survive, Melville theorizes that past events, experiences, unattended trauma, and suffering swirl within the seas of the various stages of the self, and are unwillingly “retraced”—that the self, like the great white whale, is an eternal mystery of Ifs.

There is no steady unretracing progress in this life; we do not advance through fixed gradations, and at the last one pause:—through infancy’s unconscious spell, boyhood’s thoughtless faith, adolescence’ doubt (the common doom), then skepticism, then disbelief, resting at last in manhood’s pondering repose of If. But once gone through, we trace the round again; and are infants, boys, and men, and Ifs eternally.