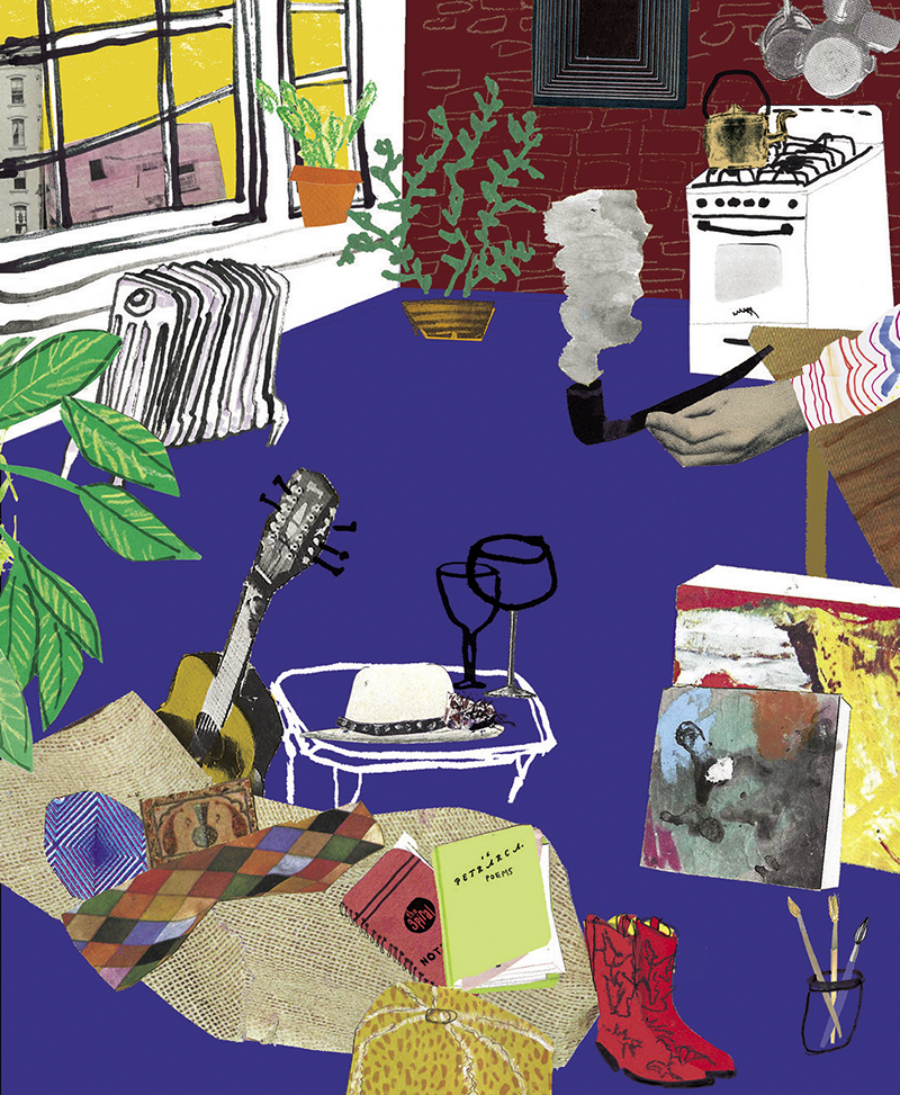

Illustration by Joanna Neborsky

In 1974, my mother was twenty years old, trying to make it as a theater actress in New York after dropping out of Bennington College. She was in a painting class led by the eccentric Ukrainian-Jewish artist Norman Raeben (the youngest child of the Yiddish writer Sholem Aleichem). One day, Bob Dylan showed up unannounced. They were painting abstracts at the time, and when it was my mother’s turn to comment on Dylan’s work she just shrugged. At first, that was the sum of their relationship: her quiet refusal to adulate Dylan’s celebrity.

One evening, after a particularly long…