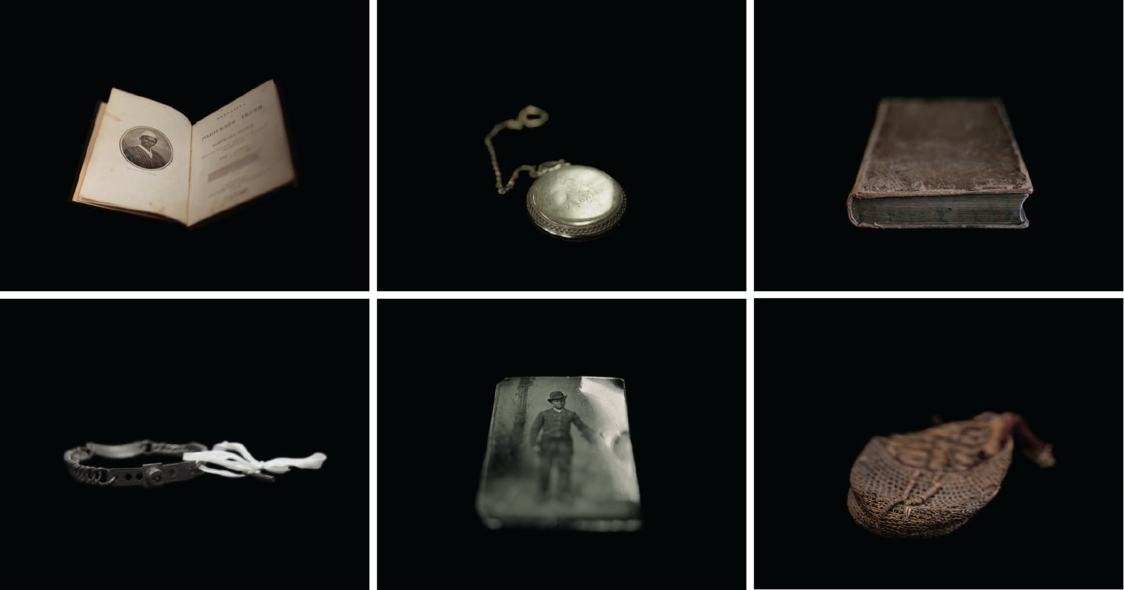

Clockwise from top left: “Narrative of Sojourner Truth (title page), 1850, Rubenstein Library, Duke University”; “Watch, Larkin Franklin Sr., Eatonville Historic Preservation”; “The Works of Robert Burns, First Book Purchased After Slavery by Frederick Douglass, Rush Rhees Library”; “Shoe, Paul Robeson House Collection”; “Tintype, Fenton History Center”; “Slave Collar, Alexander Library.” Photographs © Wendel A. White

In Teju Cole’s acclaimed novel Open City, the flaneur protagonist, Julius, navigates the streets of New York and repeatedly encounters overlooked traces of its brutal history: the lost sites of the Native and African Americans upon whose backs the modern metropolis has flourished. Just as Cole’s novel urges us to acknowledge the palimpsest of human suffering beneath the everyday, the poet and activist Clint Smith, in his first non-fiction book, How the Word Is Passed: A Reckoning with the History of Slavery in America (Little, Brown, $29), traces, in a sustained and pragmatic way, crucial sites in our historical narrative, and exposes the bitter experiences that, as Americans, we have long sought to suppress.

Originally from New Orleans, Smith comes to see that the city of his childhood has (like many others) celebrated slave-owners and Confederate generals in the naming of its streets and public squares. But this—alas, unsurprisingly—is just one small element of the willful obliteration of black history around us. Visiting first Monticello, then the Whitney Plantation outside New Orleans, the infamous Angola Prison, Blandford Cemetery, Galveston Island, and New York City, Smith reveals and makes present for his readers the profoundly disturbing truths of what transpired in these places, of the systemic and strategic violence and abuse that enabled the society in which we now live. The book ends with a journey to Gorée Island, in Senegal, from which slave ships departed for the New World. It is now a pilgrimage site for their descendants and others: in Africa, too, he encounters those engaged in the complex work of retrieving and illuminating the dark history of slavery.

In this important and compelling account, Smith, who conjures places and the people in them with striking attention to detail, exposes a gamut of responses to that history. At Monticello, Smith writes, “the plantation’s public wrestling with Jefferson’s relationship to slavery began in 1993,” part of an oral-history project called Getting Word, for which the foundation conducted interviews with the descendants of enslaved people from Monticello. It is from this project that the book’s title is taken. One result of consistent efforts in the thirty years since is a tour of the property focused on Jefferson’s relationship to slavery. But while approximately four hundred thousand people tour Monticello annually, only about a fifth of these visitors learn about slavery on the plantation. Niya Bates, then Monticello’s director of African-American history and the director of Getting Word, tells Smith that the main tour has essentially stayed the same since the Fifties. “So many people come here without an understanding of the primary cause of the Civil War,” she explains. The aim of the new programming, then, is to tell “the full truth” about Jefferson: “In order to really understand him . . . you have to grapple with slavery. You have to grapple with [physical] violence and psychological violence, and family separation.”

If, at Monticello, this concerted attempt to expand the historical narrative reaches a fifth of visitors, in some places, such as the Blandford Cemetery in Petersburg, Virginia, or Angola Prison, there is no acknowledgment whatsoever of the blood and tears of African Americans. Smith’s account of his tour of Angola Prison—a former plantation where the majority of prisoners are African-American—is particularly sinister. As he observes,

If in Germany today there were a prison built on top of a former concentration camp, and that prison disproportionately incarcerated Jewish people, it would rightly provoke outrage throughout the world. . . . And yet in the United States this collective outrage is relatively muted.

In New York City, moreover, an analogous history has also been overlooked:

Slavery was introduced to Manhattan in 1626. By the mid-18th century approximately one in five people living in New York City was enslaved and almost half of Manhattan households included at least one slave.

Major banks—among them the predecessors of Bank of America and Citibank, as well as JPMorgan Chase—profited from slavery; and the creation of Central Park involved the wholesale destruction of Seneca Village, an independent black community with around two hundred residents that existed from 1825 to 1857. Well into the nineteenth century, “Black people lived in fear that at any moment a slave catcher could snatch them or their children up, regardless of status or social position.” It is not without a bleak irony that Smith then observes,

In the twenty-first century, Black people live in fear that at any moment police will throw them against a wall, or worse, regardless of whether there is any pretense of suspicion other than the color of their skin.

The Whitney Plantation in Wallace, Louisiana, affords a reassuring counterpoint to the persistent erasure of uncomfortable facts. The plantation was purchased in 1999 by a multimillionaire from New Orleans named John Cummings, “a white person who says he has come to understand, in the last quarter of his life, the totality of the oppression that Black people have experienced.” With the assistance of a Senegalese historian named Ibrahima Seck, Cummings has created at the Whitney a “museum dedicated to slavery,” endeavoring to correct a national problem of “miseducation of the mind.” As Seck says, “Books are really good, but who can read a book? Who can have access to books? This needs to be an open book, up under the sky, that people can come here and see.”

Smith, who has a PhD in education from Harvard, is also concerned with access, and How the Word Is Passed is written for a broad audience. The narrative, though replete with historical detail, is framed around Smith’s visits to various sites, and presented through conversations with administrators, tour guides, and other tourists. The book doesn’t simply bring news of the past; it seeks to convey the urgency of that news in our troubled present.

Bonaparte’s March, by Varujan Boghosian © The artist. Courtesy Alexandre Gallery, New York City

Ruth Scurr’s Napoleon: A Life Told in Gardens and Shadows (Liveright, $28.95) serves, somewhat unexpectedly, a comparable function. The great general and sometime emperor of France has, of course, been extensively written about for more than two hundred years; but to mark the bicentennial of his death in May 1821, Scurr reexamines his life from an unexpected angle. From his youth at boarding school in Brienne-le-Château to his final months on the godforsaken island of St. Helena, Napoleon Bonaparte was an avid gardener who sought to create order and beauty in the natural world. His first horticultural endeavor may have been the small allotment allocated by the monks at school, but he moved on, with gusto, to the exhilarating and culturally important Jardin des Plantes in Paris and its outpost in his native Ajaccio, Corsica; the Tivoli gardens in Cairo (during his Egyptian campaign, 1798–9); Joséphine’s spectacularly cultivated garden at Malmaison, with its zoologically significant menagerie; and his exuberant adoption of the still-wild forest of Fontainebleau. “We are in the enchanted forest of Tasso!” he announced while riding there, referring to Torquato Tasso’s Jerusalem Delivered, a favorite of his youth. In exile, captive first on Elba and then, finally, as a British prisoner on St. Helena, Napoleon, though reduced, nevertheless turned his attention to the improvement and beautification of his surroundings. At Longwood House, on St. Helena, with the assistance of Chinese workers identified only by numbers “because their names were hard for the English to pronounce,” Napoleon, having traded his famous bicorne for a wide-brimmed straw hat, oversaw the creation of a world of sunken paths and flower beds ornamented by a pavilion, fountains, and an elaborate semicircular aviary, decorated “with Chinese motifs, including a flower basket, egret and ribbon that formed a rebus representing longevity.” According to Scurr, he believed at the end of his life that “man’s true vocation is to cultivate the ground.”

An elegant prose stylist, Scurr is above all a fabulous historian, and a vivid storyteller with a novelist’s eye for engaging detail. With the exception of the Battle of Waterloo—the most significant fighting of which took place over a garden at Hougoumont—the wars in this book occur largely offstage. Napoleon emerges not in his warrior guise but in his full humanity—wounded by his wife’s infidelity, regretting the potential scientific achievements of his youthful fantasy, dispatching a French officer to sing an aria at Haydn’s deathbed (the composer “cried tears of joy at Sulemy’s sublime singing. Then the officer went back to war and was soon killed in the Battle of Aspern”). In his final illness, he asks his doctor whether “he had ever met with a soul under his scalpel. ‘Where does the soul reside? In what organ?’ ”

History’s palimpsest emerges in these pages too, through Scurr’s accounts of modern-day places shaped by Napoleon’s vision: while his empire is the stuff of history books, his legacy as a landscape genius endures. Earlier this year, the New York Times published an article about Point Breeze in Bordentown, New Jersey. Once the site of a glorious estate built in 1816 by Napoleon’s brother Joseph Bonaparte, who emigrated to the United States after Napoleon’s exile, Point Breeze was recently purchased from a Catholic organization for the purpose of creating a public park.

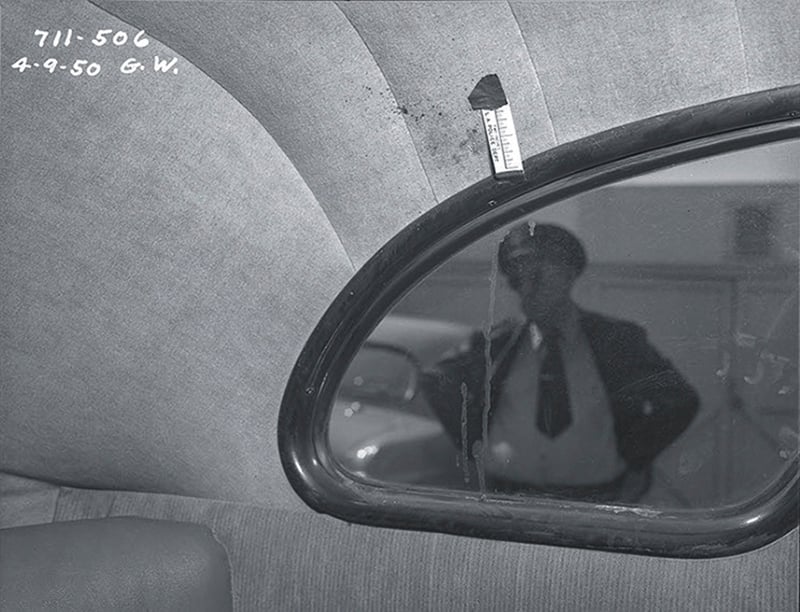

Forensic photograph by G. Wright, 1950, from the Los Angeles Police Department Archives. Courtesy the Fototeka Collection

The novelist James Ellroy is also engaged in the retrieval of lost histories, albeit in his case fictionalized ones that are so closely intertwined with fact that reality and imagination are blurred. Devotees of his work know well the seamy terrain of mid-twentieth-century Los Angeles—notably in The Black Dahlia and L.A. Confidential—in which his protagonists, themselves of dubious reputation, search for truth in the murky morass of human misbehavior. Immediately recognizable, Ellroy’s prose—an exuberant, alliterative staccato that could be described as camp noir—requires attention and some persistence. His witty verbiage can serve as pleasure and obstacle both. And perhaps needless to say, reader be warned, the world depicted in Widespread Panic (Knopf, $28) is sexist, racist, and violent, as befits the Los Angeles, and the United States, of the Fifties.

Freddy Otash, the protagonist of this elaborate thriller, is a dirty cop turned private investigator enlisted by Confidential, a gossip rag, to investigate, and if necessary manufacture, salacious stories for its pages. The novel is structured as a posthumous confession, recounted from purgatory:

There’s Purgatory for guys like me—caustic cads that capitalized on a sicko system and caused catastrophe. I’ve sizzled in my sins for two decades plus. I’ve relived my earthly life in dystopian detail. My cunning keepers are currently dangling a deal:

Record your jaundiced journey. Trumpet the truth, triumphant. Hop to Heaven, and hit that high note.

Baby, it’s time to CONFESS.

This conceit is largely unobtrusive, and Ellroy plunges us directly into the sub-rosa antics of Hollywood celebrities and politicians, rife with threesomes, drugs, and pornography (referred to, in the parlance of the time, as “smut”), shadowed by Cold War politics and underworld brutality. Here, too, the past is exposed as the forebear of our present: as Freddy muses about the city in the fall of 1953,

It’s the egalitarian epicenter of postwar America. It’s a colossal convergence of the gilded and gorgeous, the defiled and demented, the lurid and the low-down. This seedy summit set the tone for the frazzled and fractured frisson that is our nation today.

Ellroy’s midcentury Los Angeles, evoked with landmarks such as the Hollywood Ranch Market, Ollie Hammond’s All-Nite Steakhouse, the Beverly Hills Hotel, and Googie’s Coffee Shop, teems with celebrities major and minor. We meet Rock Hudson, Elizabeth Taylor, and Marlon Brando alongside Joi Lansing, June Christy, and Lois Nettleton. Freddy beds Liz Taylor, hangs out with James Dean, and provides women for and spies on Senator Jack Kennedy:

Mattress Jack was a hellacious hophead. He had legal scripts from half the pharmacists in L.A. . . . Jack collected lissome locks of women’s pubic hair. He traveled with them and kept them in unscented sachets.

The novel’s complex plot involves a Communist cell run by a society columnist named Connie Woodard, the film director Nicholas Ray and his perverse hold over the young cast of Rebel Without a Cause (not only Dean, but sixteen-year-olds Natalie Wood and Sal Mineo), and the convicted kidnapper and rapist Caryl Chessman, who was condemned to death for his crimes and taken up as a clemency cause by numerous celebrities and intellectuals.

Freddy Otash, enlisted first to organize a mariage blanc for Rock Hudson (his actual wife, Phyllis Gates, features here), and then to provide an alternate love interest, hires an ingenue named Janey Blaine for the role, only for her to turn up murdered. A preppy sometime prostitute, Blaine has connections to Kennedy as well as to Hudson and Otash. Freddy pursues the truth for his own peace of mind—even as he’s party to the police murder of a man falsely accused of Blaine’s murder. “The Chief looks askance at your fixation with dead and brutalized women,” one cop friend tells him; “No more dead-woman crusades, Freddy,” says another. “That’s over and out.”

Revealing the true circumstances of Blaine’s murder is Freddy’s posthumous bid to escape purgatory. But there is here, as in Ellroy’s other novels, so fully researched and plausible an evocation of the world about which he writes, so deft an intermingling of the real and fictional characters that the novelist asks the reader to believe that these events could have happened, and that some of them (Jack Kennedy’s exhaustive and exhausting philandering, for example) probably did. This commingling of fact and fiction is, of course, the basis upon which the myths of Hollywood, and hence, at this point, those of our broader American culture, rest. As Ellroy says, it “set the tone for . . . our nation today”—an unsettling reality that merits consideration.