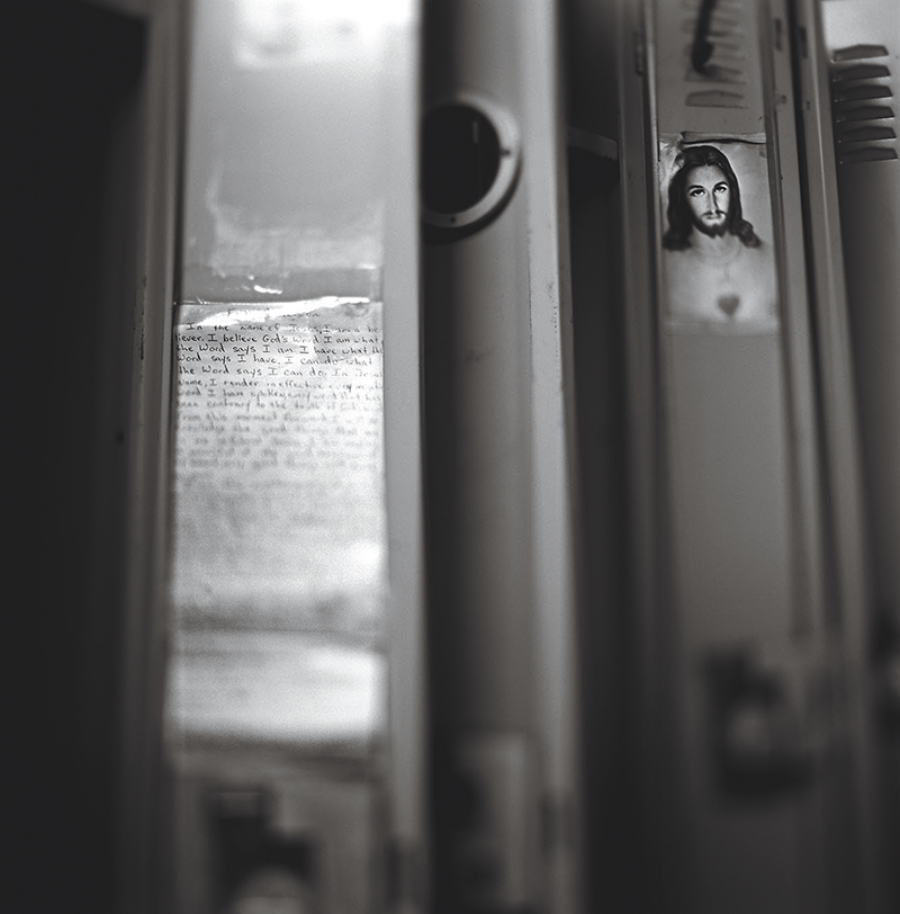

“Locker Room Jesus,” by Bill Vaccaro © The artist

Discussed in this essay:

Crossroads, by Jonathan Franzen. Farrar, Straus and Giroux. 592 pages. $30.

The first half of Jonathan Franzen’s new novel, Crossroads, centers on an improbable church youth group in the near western suburbs of Chicago during the final days of 1971. The improbability is twofold. First, the group’s size: it’s enormous, drawing more than a hundred adolescents—a population one might associate with a megachurch, but not a mainline Protestant congregation in an inner suburb, which is the setting here. Second, it . . . well, it’s just not religious. There are no readings from Scripture, Jesus is…