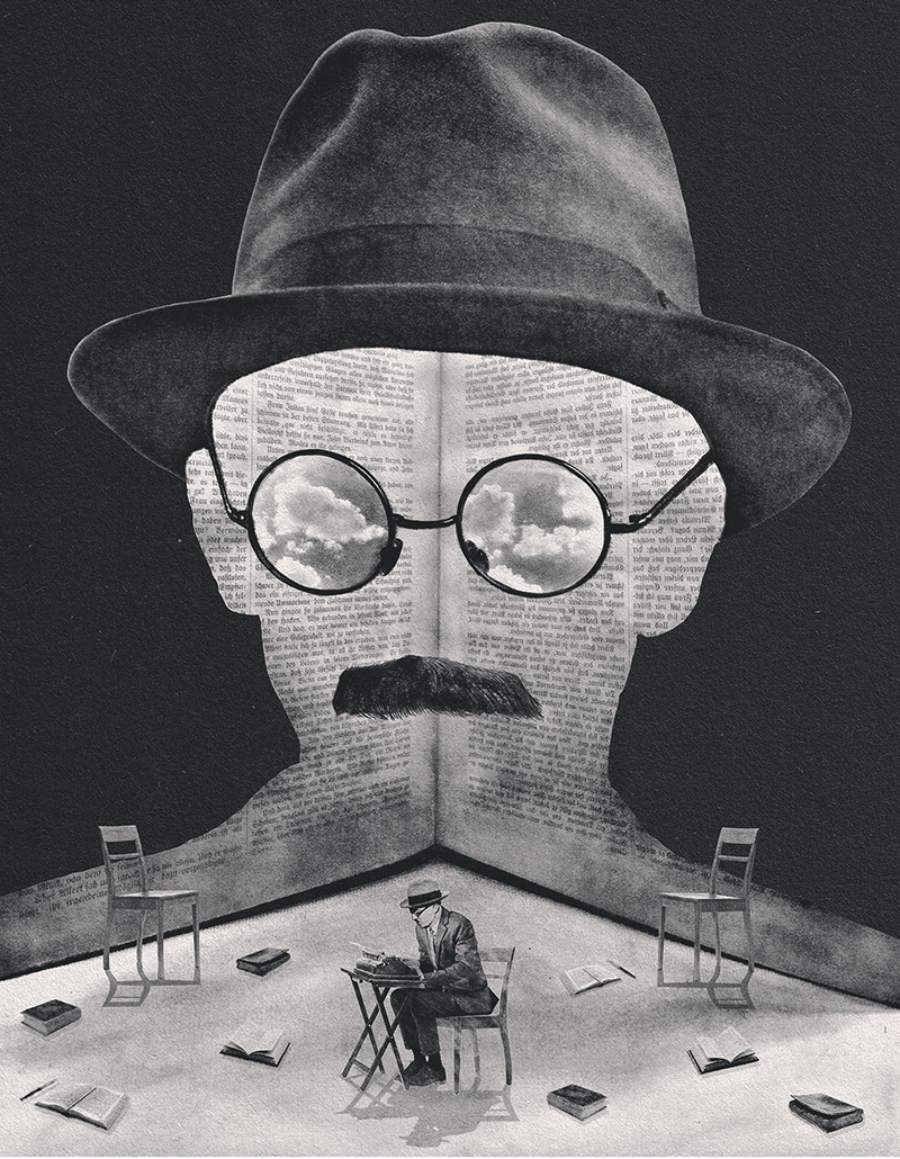

Illustration by Zach Meyer

Discussed in this essay:

Pessoa: A Biography, by Richard Zenith. Liveright. 1,088 pages. $40.

How to write the biography of a man who scarcely lived? This is the problem facing anyone who would venture a life of the Portuguese poet Fernando Pessoa. In the voice of one of the dozens of writerly personae he came to adopt—Pessoa called these scribbling alter egos his “heteronyms”—he declared that if people “knew how to feel the thousand complexities which spy on the soul in every single detail of action, then they would never act—they wouldn’t even live.” It’s in our imagination and anticipation, in other words, that true richness of experience lies; actually to do, to act, to live can only impoverish our being and traduce our souls. And Pessoa attempted to prove this doctrine on his pulses, meditating and feeling a great deal over the course of his life but otherwise doing very little. A pagan sensualist who seems to have died a virgin (he did kiss a sweetheart once), and a polyglot internationalist who disdained travel (“You can be happy in Australia, as long as you don’t go there”), Pessoa had no use for life except as a pretext for literature. Even so, he produced just one slim book in Portuguese while he lived.

His modest and abbreviated biological existence is of interest as the prelude to an extravagant posthumous career, which has revealed Pessoa as one—if not indeed, through his heteronyms, several—of the most remarkable writers of the twentieth century. To write under a mere pseudonym, he explained, is simply to disguise oneself, while to use a heteronym is to shed the familiar self and adopt a different one. All three of his major poetry-writing heteronyms, with their distinctive and incompatible orientations to life—a holy simpleton of a shepherd, a moody naval engineer, and a stoical medical student turned Latin instructor—are impressive modern poets, as is Pessoa under his own name. Internationally, the poetry began to receive its due in the 1960s, decades after Pessoa’s death, with appreciation from Octavio Paz, the linguist Roman Jakobson, and Michael Wood in The New York Review of Books. In 1991, the publication of four separate translations of The Book of Disquiet, mimicking Pessoa’s own self-multiplication, revealed a fragmentary prose masterpiece that rivals the unfinished novels of Franz Kafka and Robert Musil as a testament to the peculiarly modern experience of a fatally suspended, as-if sort of existence. A congeries of abstractly confessional passages—some as curt as a single line, others sighing over a page or two—stuffed by Pessoa into a wooden trunk and discovered only after his death, The Book of Disquiet is, as arranged into different sequences by various editors, an alternately melancholy and exultant account of an unlived life. Here is a man too faithful to his imagination to spoil it by fraternizing with the actual world; and then here, on the next page, is a man who badly regrets having added, to all the customary pains of life, the optional agony of never having lived.

Pessoa’s real achievement, however, is to be seen less in this or that particular work than in the lucid incoherence of his total output. In his work self-consistency is the height of self-betrayal. He and his heteronyms insist with thrilling literalness that a single person can and should host multiple personalities. “The greatest man is the one who is the most incoherent,” a manifesto signed by the imaginary naval engineer Álvaro de Campos proclaimed. “Instead of thirty or forty poets to give expression to the age, it will take, say, just two poets endowed with fifteen or twenty personalities.” Alas, the cultivation of trial personalities requires one to abstain as much as possible from participation in the brutally singular world of flesh and blood, where realizing any one possibility means canceling out countless others. The overall Pessoan effect—of fertility and nullity overlaid, of a teeming garden spied through the transparent body of a phantom—gathers into a single sensation extremes of modern exuberance and despair. Here we have the abounding potential of a world liberated from tradition, and on the other side of the coin, the fathomless solitude of a world bereft of community. Just look at all the people you could be, if only you could be anyone at all.

In Pessoa: A Biography, the writer’s longtime translator Richard Zenith has improved upon the jest inherent in any full-length biography of a timid slacker by writing one more than a thousand pages long. Born the first child of a bourgeois family in Lisbon on June 13, 1888, Fernando António Nogueira Pessôa—he dropped the circumflex when he was eighteen—had in a sense already made fun of Zenith’s undertaking in the very moment of his baptism, given that the word pessoa simply means “person.” Aware of the generic quality of his family name, Pessoa was amused to invent characters whose surnames produced the same effect in English, the language in which Pessoa first tried to become a writer. One was called Ferdinand Sumwan (read: someone). Another went by the name of Charles Robert Anon. Had Pessoa made it into old age, he might have smiled to encounter Hugh Person, the protagonist of Nabokov’s Transparent Things.

Instead he died in his forties. In this and other respects he resembled his father, a diffident, tubercular music critic and freethinker, who declined last rites and expired just after Fernando’s fifth birthday. (In a poem written on his forty-second birthday, Pessoa would recall a boyhood “back when they used to celebrate my birthday / I was happy and no one was dead.”) Pessoa’s younger brother Jorge followed their father into the grave half a year later, and it doesn’t seem outlandish to note, apropos of the cohort that came to populate Pessoa’s inner life, that one advantage of imaginary people over real ones is that the former can’t die on you. Pessoa’s mother, Maria Madalena, was the most robust member of the household, and in the same month that her younger son died, she boarded a horse-drawn streetcar called an americano and encountered a handsome ship captain with whom she promptly fell in love. (Álvaro de Campos would many years later observe in a poem: “The lady who lives at #14 was laughing today at the door / Where a month ago her little boy was carried out in a coffin.”)

Captain Rosa was soon named Portuguese consul in Durban, South Africa, and Pessoa’s precocious first poem, “To My Dear Mother,” composed when he was seven and duly recorded by its addressee, constitutes a plea that Fernando not be left behind with relatives in Lisbon when his mother sails for the Cape of Good Hope to join her new husband. Since Pessoa’s mother was herself an amateur poet, sometimes writing poems to her son, this mode of communication must have come naturally. Pessoa would spend most of the next decade in Durban, and Zenith reasonably conjectures that expatriation at such a young age, into the household of a stepfather, no less, to which five half siblings were rapidly added, contributed to Pessoa’s lifelong attitude and posture as a stranger. Zenith cites The Book of Disquiet: “I was a foreigner in their midst, but no one realized it . . . a brother to all without belonging to the family.”

In Durban, Pessoa’s more intimate family consisted of the imaginary personages multiplying in his schoolboy composition books. The list of characters at the beginning of Zenith’s tome tabulates not historical figures, as in an ordinary biography, but forty-seven heteronyms Pessoa floated over the course of his life, with dozens more left unmentioned. According to an astrological chart the adult Pessoa drew up, the physician Ricardo Reis was the eldest of this group, having been born some nine months before Pessoa himself. In actuality, the first of the heteronyms to debut was one Chevalier de Pas, a French knight in whose name Pessoa wrote letters to himself at the age of five or six.

Much of Pessoa’s social isolation in Durban was racial. He was neither an Afrikaans-speaking Boer, nor, like most of his classmates, a native English speaker and British subject; nor did he belong to the city’s substantial Indian population, where another resident, Mohandas K. Gandhi, cut his teeth as a militant by agitating for civil rights for South Asians. (In the 1920s, Pessoa would draft an essay—unfinished, like most of his projects—in which he declared Gandhi “the only truly great figure that exists in the world today,” because, “in a certain sense, he does not belong to the world and he denies it.”) Nor, of course, were Pessoa or the rest of his stepfather’s family black Zulu speakers, like the dispossessed native population of the region. Pessoa had the aquiline Semitic features of his late father’s side, which included Jewish conversos frog-marched into Christianity during the Inquisition.

The most harmless version of modern communalism is passionate fandom for a sports team, but even here Pessoa remained an outsider. As a teenager, he organized soccer matches between imaginary clubs of his own devising, dreamt up corresponding managers, and duly recorded kickoff times and scores. If the adolescent Pessoa felt at home anywhere, it seems to have been in the English language, which he commanded well enough to win the University of the Cape of Good Hope’s Queen Victoria Memorial Prize for best essay in 1903. Later on, he proved himself enough of a versifier in English that the two chapbooks he self-published in the language received respectful reviews in the United Kingdom.

It must have stung Pessoa, nevertheless, when an otherwise receptive critic noted that his excellent English retained the awkward shape of a borrowed garment. In truth, the Portuguese writer had stumbled into the sweet spot of many a modern poet: knowing a foreign language well enough to imitate its best writers, but not so well as to be a viable, idiomatic stylist in it. Doing one’s best to rip off the signature effects of admired foreign writers can produce truly original results in one’s native tongue. The case of the mature Pessoa somewhat resembles that of Jorge Luis Borges, in which a writer working in what he feels to be a humidly sentimental Iberian idiom borrows from English-language models a tonic quality of the dry, the humorous, and the analytical, in this way distilling a tone previously unknown in either language. But Pessoa’s English-inspired breakthrough in Portuguese poetry still remained some years away, in 1905, when he departed South Africa for his native Lisbon, with the idea of living with relatives while finding his feet and continuing his education.

His college days didn’t last long. When students at the School of Arts and Letters in Lisbon went on strike over the repression of republican colleagues in what remained a tottering monarchy, Pessoa decided to drop out once and for all. An inheritance from his mad grandmother Dionísia allowed him to move into his own apartment and establish a press, with which he planned to publish his translations of Shakespeare and Poe as well as of Robert Louis Stevenson’s Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde; a gymnastics manual; and his own poetry and prose. Assisting him in the enterprise were heteronyms such as Carlos Otto, who translated detective fiction, Joaquim Moura-Costa, the author of an anticlerical lampoon, and Vicente Guedes, who later added pages to The Book of Disquiet. In the end, the Ibis Press did some error-ridden printing on behalf of clients, and put out nothing at all under its own imprimatur. For the remainder of Pessoa’s life, his modest income mainly came from translating business letters into English or French for various Lisbon firms, and cadging funds from indulgent relatives.

Pessoa first began to publish work in Portuguese in the 1910s, in the new literary magazines then proliferating in Lisbon. In a 1912 essay, he argued, with the grandiosity native to little magazines, that advances in a nation’s literature prefigured its political progress. It followed that a Portuguese literary renaissance in the twentieth century, to be spearheaded by a “Great Poet,” would foretell the “glorious future awaiting the Portuguese Nation.” Civilizational renewal by way of poetry constituted a tall order in one of the smallest, poorest, and least politically stable countries in Europe (between 1910 and 1925, Portugal ran through forty-five governments), especially when only a quarter of the population could read. It is a part of Pessoa’s divided nature that his shyness and passivity coexisted with vainglorious ambition, and that in his tremendous solitude he conceived a new society.

The first mature poems signed by Fernando Pessoa appeared in another short-lived journal in the blithe first half of 1914. One of them, “Swamps”—a soup of images pregnant with undisclosed significance—supplied the model for the “swampism” that Pessoa and his fellow poet Mário de Sá-Carneiro, perhaps the one close friend of Pessoa’s life, promoted as a sort of aggravated Symbolism. But Pessoa soon discovered himself a more lucid and original poet, or set of poets, when he wrote under different names and according to other programs. The early twentieth century was literature’s great Age of Isms, and, in addition to swampism, Pessoa would at different times propose the doctrines of “sensationism,” “intersectionism,” and “neopaganism.”

Not until the late 1920s did Pessoa begin to characterize the bearers of such outlooks as heteronyms. Still, the galaxy of the major heteronyms underwent its big bang on March 8, 1914, as he explained to a young critic twenty-one years later. Pessoa had intended to invent “a rather complicated bucolic poet,” tricked out with a fake biography, to hoodwink his friend Sá-Carneiro into accepting his invention as real:

I spent a few days trying in vain to envision this poet. One day when I’d finally given up . . . I walked over to a high chest of drawers, took a sheet of paper, and began to write standing up, as I do whenever I can. And I wrote thirty-some poems at one go, in a kind of ecstasy I’m unable to describe. It was the triumphal day of my life, and I can never have another one like it. I began with a title, The Keeper of Sheep. This was followed by the appearance in me of someone whom I instantly named Alberto Caeiro. Excuse the absurdity of this statement: my master had appeared in me.

Zenith’s archival sleuthing has revealed that this account is neater than the truth—Pessoa in fact drafted his cycle of poems over ten days, and didn’t immediately attribute them to the made-up Alberto Caeiro—but there is no reason to doubt the experience of a renovated life and newly begotten writerly enterprise that Pessoa describes. All of the important heteronyms amount to hypothetical ways of being in the world, and the hypothesis that sponsors Alberto Caeiro is that of a metaphysical innocence in which a Portuguese shepherd of the twentieth century replaces Adam as a sort of first man, and merely sees things for what they are, outside of any thought. “To not think of anything is metaphysics enough,” Caeiro says in one poem. In another he counsels that it “requires deep study, / Lessons in unlearning,” to arrive at the place where “after all the stars are just stars / And the flowers just flowers, / Which is why we call them stars and flowers.” The appeal of such a perspective to a helplessly intellectual young man, barely capable of crossing the street without developing a theory of pedestrianism, is easy to imagine.

Pessoa killed off Alberto Caeiro with tuberculosis in 1915. By this time, the heteronym Álvaro de Campos, who hailed Caeiro as his master, was submitting poems to the journal Orpheu, founded by Pessoa and some of his friends, whose narrow range of contributors might have seemed even narrower had works by both Pessoa and de Campos not appeared in its pages. (For all the philosophical richness of the heteronyms, one shouldn’t ignore their practical usefulness in bulking out a list of contributors.) De Campos, arguably the best poet among the heteronyms, not to mention a more original one than Pessoa in his own name, joins Pessoa’s taste for philosophical abstraction to the headlong rhythms of Walt Whitman, whose influence shines through more clearly here, as in Federico García Lorca or Pablo Neruda, than in any twentieth century poetry in English.

De Campos’s long poems are among Pessoa’s tallest achievements, and, like symphonies, owe much of their stature to their duration. Nevertheless, a stanza from “Time’s Passage” may correctly suggest that if you know what’s best, you’ll immediately search out the whole unfurled oration:

I multiplied myself to feel myself,

To feel myself I had to feel everything,

I overflowed, I did nothing but spill out,

I undressed, I yielded,

And in each corner of my soul there’s an altar to a different god.

A seaman like Pessoa’s stepfather, de Campos seems to represent Pessoa’s idea of an erotic and vagabondish sensibility available, as Pessoa himself was not, to sex and travel and outward displays of rapture or distress. Even so, the sensation of an unlived life persists. “Maritime Ode,” another of de Campos’s magnificent long poems, speaks from the point of view of a man who can’t stand on shore and watch a single ship dwindle into “a vague point on the horizon” without feeling that it is his own life leaving him with

. . . nothing, and only I and my sadness,

And the great city now filled with sunlight

And the real and naked hour like a quay no longer with ships,

And the slow turning of a crane, like a swinging compass,

Which traces a semicircle of I know not what emotion

In the aching silence of my heart

Last, and frankly least, of the main versifying heteronyms is Ricardo Reis, a Portuguese high school teacher in Brazil who accounts himself both a Stoic and a pagan. (Of all the dispositions that Pessoa entertains, Christianity is conspicuously absent.) Unlike de Campos, with his cascading stanzas, or Caeiro, with his beatific free verse, Reis writes formal quatrains that emphasize the vanity of existence and recommend acceptance of one’s fate: “Love and glory / Don’t matter to me. / Wealth is a metal, glory an echo, / And love a shadow.” The quality of ancient self-help may bring to mind Epictetus or Marcus Aurelius, but with some of the modern willfulness and unconvincingness of a yoga instructor who looks as though he might cry for reasons not comprehended by his philosophy. Reis’s Stoicism is perhaps most moving for his inability to persuade the other heteronyms of any such thing.

Álvaro de Campos had been vigorous and thirsty for experience, and his evaporation after 1928 may be taken to indicate Pessoa’s abandonment of the world. Pessoa began to write fragmentary prose in the voice of someone called the Baron of Teive, whose aristocratic nature is confirmed by suicide: “I feel I have attained the full use of my reason. And that’s why I’m going to kill myself.” This had been the choice of Sá-Carneiro, who put on his best suit and swallowed strychnine in a Paris hotel in 1916, depriving Pessoa of his best friend. A disastrous love affair lay behind Sá-Carneiro’s act, but such passion was not Pessoa’s or the Baron’s style. In 1929, Pessoa renewed his acquaintance with a young woman named Ophelia Queiroz, with whom he’d shared a kiss and exchanged love letters a decade earlier. According to Zenith’s carefully circumspect reconstruction of Pessoa’s erotic nature, he seems finally to have been less heterosexual than homosexual, and less homosexual than asexual. At any rate, Ophelia’s relationship with her indecisive Hamlet went nowhere a second time. “I passed by the general phenomenon of love,” the Baron of Teive says calmly, “as I passed, more or less, by the general phenomenon of life.”

Pessoa’s most prolific alter ego, the assistant bookkeeper Bernardo Soares, he deemed only a semi-heteronym: “me minus reason and affectivity”—that’s all. Soares spent Pessoa’s last years stuffing pages into the latter’s wooden trunk. To be sure, Soares/Pessoa often denigrates life, action, travel, and love in familiar fashion, insisting that experience can never amount to anything but a mockery of the imagination. Elsewhere, however, they inquire, with a kind of clinical coolness, whether this flight from suffering may not have plunged them directly into pain:

My self-imposed exclusion from the aims and directions of life, my self-imposed rupture with any contact with things, led me precisely to what I was trying to flee. . . . With my sensibility heightened by isolation, I find that the tiniest things, which before would have had no effect even on me, buffet and bruise me like the worst catastrophe.

Pessoa died on November 30, 1935. An intestinal blockage seems to have done him in, but Zenith does not rule out acute pancreatitis, as a result of heavy drinking, for this dire alcoholic—“the family drunk,” as he cheerfully announced himself on one occasion—whose acquaintances related that he never seemed intoxicated. What are we to make of Pessoa’s meager earthly career and prolific afterlife? It’s easy to celebrate the vast triumph of the work and pity the small sadness of the life, until you realize that the vastness of the work was premised on the smallness of the life, and vice versa.

Discussion of Pessoa’s body of writing by now amounts to a huge, critical, and sometimes imaginative literature, including several novels in which he figures as a character. Amid this warm fog of words, two statues stand out. Both the late Portuguese novelist José Saramago and the French philosopher Alain Badiou take the inventor of heteronymity at his word: he really was multiple people in one. In Saramago’s 1984 novel The Year of the Death of Ricardo Reis, Pessoa’s stoical doctor returns to his native Portugal to learn that his old friend Fernando Pessoa has just died. Pessoa himself soon visits Reis from the grave, explaining that we fade out of existence over a stretch of nine months that matches the gestation period. A melancholy dialogue between a ghost and his creation ensues, while Reis moons ineffectually over a young woman with an immobile arm, and the Portuguese strongman António de Oliveira Salazar consolidates his dictatorship. The impression, admiring but overwhelmingly sad, is of a baroque futility, both political and erotic.

For Badiou (like Saramago, a writer of communist convictions), Pessoa instead presents a heroic image. “One of the decisive poets of the century,” he pioneered a mode of understanding to which the discipline of philosophy, “not yet worthy of Pessoa,” can only aspire. Flouting the principle of noncontradiction, Pessoa, with his incompatible convictions, promises a future way of thinking that “does justice to the world” as a “philosophy of the multiple, of the void, of the infinite.” In Badiou’s own work, a quartet of separate and incommensurable “truth procedures” correspond to the four distinct realms of love, politics, science, and art. He seems to view Pessoa as the prophet of a new way of being that can attend at one and the same time to events that occur in the disjunct registers of our existence.

Badiou’s mathematical language provokes the fundamental question: Was the basic operation of Pessoa’s life one of division, so that he ended up a sad fraction of a person? (Surely this lonely, unfulfilled celibate missed out on more love and companionship, more publication and recognition, and simply more years than was strictly necessary?) Or do we behold instead a case of glorious multiplication, in which a crew of inward persons voyaged beyond the confines of the sole self? It would, of course, violate the spirit of Pessoa’s work—his insistence on having things both ways—to pronounce his life either a cautionary tale or a hero’s journey. And yet the nature of biographies is to bolster tragic, not affirmative, conclusions: in the end, one has only a single life that’s never what it could have been.