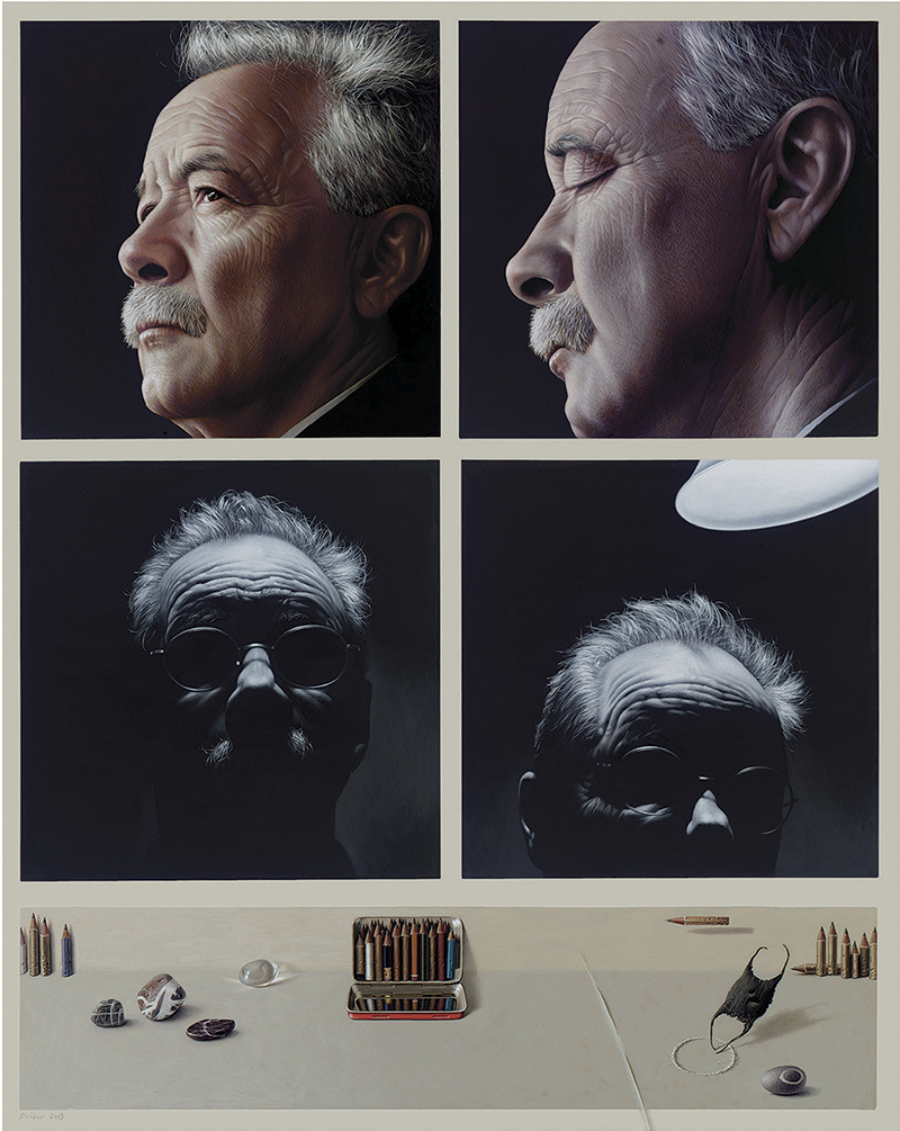

L’Oeil oder die weisse Zeit (The Eye or the White Time), by Jan Peter Tripp. Courtesy the artist and Galerie Schmalfuss, Berlin

Discussed in this essay:

Speak, Silence: In Search of W. G. Sebald, by Carole Angier. Bloomsbury. 640 pages. $32.

In mid-August of this year I traveled from Berlin to the small town of Sonthofen, in the Allgäu region of southern Germany, to research an article about the author W. G. Sebald, who grew up there and is the subject of a recent biography. Sebald’s fiction almost always begins with the narrator going on a journey, partly for the purposes of research and partly for reasons he cannot identify, and I believed that the huge sense of aimlessness which had towered over me for months, having nothing to do with Sebald, would help me to understand the methods of an author whose appeal had always eluded me. I spent the days before my departure in a state of frantic dread, unable to imagine embarking on what promised to be an unrelentingly pleasant excursion to a region of striking beauty. As I finished the preparations for the journey, dashing to and fro under the linden trees of central Berlin, I passed the threshold of the Zeughaus and remembered standing there following a lecture years before. Once again, I saw familiar scenes of fire and ruin flicker over my strident surroundings, the Bebelplatz, the unfinished Humboldt Forum, the Nikolaikirche, and it all seemed to me unbearably false, as if cities exist always in another time, in their natural state of total destruction, and any effort at regeneration only provides further evidence of the pitilessness of humanity. It was then that all my potential difficulties appeared before me as if dark, insurmountable obstacles. There was nothing new to be said about Sebald in his defense, and my objections to his work would not be well received. A transit strike, of the smaller of the two unions representing Germany’s train drivers, threatened. And after much vacillation Jeffrey decided that he did not want to accompany me, as he had already seen the real Alps, as he calls them, in Austria and Switzerland, and felt more than satisfied learning that Sebald, whose work he does not admire, hailed from what are merely foothills. I was once given a recording of Sebald reading as a gift, he told me, and I dutifully brought it with me every time I moved, from Princeton to Philadelphia, to Greenpoint, to Binghamton, and finally, when I re-encountered it recently in the boxes I brought to Ithaca, I threw it in the trash. Was also beudeutet es wohl? It meant that once I arrived in the Allgäu I would have to drive myself. I have long avoided driving in foreign countries in general and on the autobahn in particular, and the circumstances seemed to portend the realization of my fearful reasoning. Sebald, who died of a heart attack behind the wheel in December 2001, at the age of fifty-seven, was a terrible driver, prone to veering distraction, and although I have the opposite problem, overcautiousness, it did not assuage my superstition that to motor around his hometown would be to court death, as his work is concerned not only with death but also with random connections and coincidences, down even to the most tedious details such as dates and times, and it would not take very much for any car accident that I had while working on this article to feel, as Carole Angier, the author of the new biography, would say—over and over again, perhaps to the point of irritation—Sebaldian. It is just like driving in New York, said Jeffrey, except that there aren’t holes in the road. It was only at the last minute, as it were, that I managed to leave the small apartment we were borrowing from a friend to catch the train. Making a joke at the expense of my lamentable German, whose necessary use in Bavaria had become another source of anxiety, we proposed that I might differentiate my piece by asking of everyone I saw, from the spiritless hotel employees to the tourists, who, with their fiery shoulders, appear almost Mephistophelian, a question that Angier fails to answer in any satisfying manner: Kennen Sie Sebald?

Okay, that’s enough. I don’t want to write a book review without quotation marks, and I flatter myself to think that I’ve been tilting into Bernhard, whom Sebald admired but whose style is more ironic and forceful, perhaps in part because Bernhard is from Austria—a country whose intellectuals are, like its Alps, decidedly more hardcore. (Sebald, who was known to tell people he was Austrian, or at least let them think he was, would agree. Though in his defense, you could walk to Austria from his house.) This is not a takedown, but I’m also not here to reheat the bland appreciation for Sebald shared by what feels at times like everyone I know. Since The Emigrants was celebrated by Susan Sontag as “an astonishing masterpiece” in 1996, he’s been praised by Cynthia Ozick, J. M. Coetzee, Nicole Krauss, Robert Macfarlane, and James Wood, among many others; in the English-speaking world, he’s become about as popular as an experimental author of what his friend, occasional translator, and The Rings of Saturn muse Michael Hamburger called “essayistic semi-fiction” can be. In 1998, the British satirical magazine Private Eye published a parody of his writing, and Sontag set him up with her agent, Andrew Wylie, who got him a “telephone-book number” advance, as one newspaper had it. By the time Austerlitz was published in German, in early 2001, he was so busy that he would get rid of unknown callers by saying he was in the middle of committing suicide.

Carole Angier’s Speak, Silence is the first major biography of Sebald to appear in any language, and her approach both confirms his swift canonization in the Anglophone world and suggests there is something a little weird about it. What accounts for his dizzying ascent? “What he is most famous for is that his books are uncategorisable,” Angier writes. “Are they fiction or non-fiction? Are they travel writing, essays, books of history or natural history, biography, autobiography, encyclopaedias of arcane facts?” Yes to all—he has in fact been credited with the creation of a new genre. His books, as Wood put it, have been “released from the formulas of falsity that contaminate much realistic fiction—drama, dialogue, the pretense of ‘real time,’ the cause-and-effect of motive.” As the poet and essayist Elisa Gabbert wrote recently, Sebald “has been so widely influential you almost don’t have to read him.” His obvious descendants include Olga Tokarczuk, Ben Lerner, Rachel Cusk, Teju Cole, and the awesome Daša Drndic; in the past year alone, writers for The New Yorker have invoked Sebald in articles about Karl Ove Knausgaard, Antonio Muñoz Molina, Sunjeev Sahota, Katie Kitamura, Sarah Moss, and Kazuo Ishiguro, as well as in a story about American air strikes in Syria. Anytime you encounter a text that involves what the novelist Sam Pink calls “the dreaded tidbit”—“the recently popular thing of doing like, little book reports in the book”—you have Sebald to thank. He is also responsible, I believe, for the tendency of contemporary authors to be walking along Seventh Avenue and suddenly remember a thematically appropriate passage from Sir Thomas Browne. In a 2013 interview with The White Review, Javier Marías affirmed that he was a Sebald fan while casually rejecting the suggestion that he had gotten the idea to put photographs in a novel from Sebald, citing incontrovertible timelines; Geoff Dyer has been on a yearslong campaign to correct anyone who says the same of him. “I was doing the ‘part essay, part travelogue, part fiction’ thing before Sebald invented it!” he wrote in the now defunct comments section of why you should read w. g. sebald, a New Yorker blog post from 2011. Though he, too, admires him.

It is one thing to acknowledge undeniable influence; it is another to say, as Angier does, that Sebald is sui generis, “the most revered twentieth-century German writer in the world,” and the only German, “or the only one I know, who suffered from survivor’s guilt” after World War II, “though he had nothing to do with it at all.” “Not since Montaigne,” wrote Joyce Hackett in 1998, “has an author bound such a breadth of passion, knowledge, experience and observation into such a singular vision.” Wouldn’t it be nice, I thought as I accepted this assignment, to feel a passion that drove me to publish such ludicrous statements? But if I couldn’t be converted, I wondered whether Sebald’s might prove the level of excellence at which I could experience that rare thing, a respectful difference of opinion.

Born in the village of Wertach in 1944, Winfried Georg Sebald grew up in a staunchly Catholic family, the son of a Hausfrau, Rosa, and a Wehrmacht officer, Georg. When he learned what a Wehrmacht officer was, at some point during his adolescence, he became aghast and enraged; from his teens, he was “anti-bourgeois, anti-military, anti-clerical, anti-establishment,” fighting bitterly with his father when he wasn’t ignoring him. The teenage Sebald was an archetype: a natural athlete who wore scandalous blue jeans sent over from his aunt in America, he would recite Goethe by a local waterfall and seemed to his friends “like a prince—intense, handsome, romantic.” In high school no girls were able to make any progress with him, until he got together with the worldly hairdresser he would later marry. He left the Allgäu, which had been untouched by the war—except that there he had never met a Jewish person—as soon as he could, and after two years spent experimenting with theater and lightly tormenting conservative Freiburg as a member of the university’s “practically communist” dorm, he felt he had to get farther away. Following stops in Switzerland and Manchester, he ended up in Norwich, in England, where he was a professor of European literature until he died. Save for a failed stint training to be a German teacher in Munich, he never moved back to Germany; in his early twenties, he abandoned his stuffy patriarchal name, Winfried Georg, and started going by Max, for various offbeat reasons. “I felt increasingly that the mental impoverishment and lack of memory that marked the Germans, and the efficiency with which they had cleaned everything up,” he writes in The Emigrants, “were beginning to affect my head and my nerves.” He was seventeen when, on a bright spring day, a teacher showed his class Billy Wilder’s film about the liberation of Bergen-Belsen; it marks the moment when the disjunction between his bucolic childhood and “the monstrous events in the background” began to “cast a very long shadow over my life.” That damage—called “trauma” by Angier—is present in all his writing. Although it is removed, the result of learning rather than experiencing, it enables him to see, and feel, death and destruction everywhere, from the creep of Dutch elm disease that represents nationalism in The Rings of Saturn to the construction of Antwerp’s central train station.

His books include some academic monographs in German; After Nature, a book-length poem; Vertigo, The Emigrants, The Rings of Saturn, and Austerlitz, the four essayistic semi-novels he’s best known for; A Place in the Country and On the Natural History of Destruction, two collections of essays; and two sets of what Angier calls “mini-poems,” which were published in collaboration with the artists Tess Jaray and Jan Peter Tripp. The fictions are collages, but always framed by a distant Sebald-like narrator whose “sense of aimlessness and futility” generates a mood of gauzy but inescapable disquiet. In Vertigo and The Rings of Saturn, the narrator operates closer to the center, as the texts follow his wide-ranging thoughts and encounters on semipurposeless travels; The Emigrants and Austerlitz are organized around fictional characters whose painful stories the narrator researches or receives, alongside Sebald’s trademark digressions. The subjects of these digressions are, at first glance, idiosyncratic (herring), but his fictions are stunningly consistent, such that it makes sense to think of them as different versions of the same thing. His major themes include the Third Reich and the Holocaust, architecture and ruins, exile, the destruction of nature, the lives of writers and other intellectuals (which he often manipulates to suit his purposes), memory, and time. His recurring images include trees, veils, skulls, fire, ice, mist, ash, dust, silk, pigeons, a probably but not definitely dead body, and, twice, copulation witnessed accidentally, presaging horror. Someone is always having a very meaningful dream, often “paradoxically much clearer” than memory, which is usually being repressed to moving effect. There are also, famously, the photos, grainy black-and-white images that he often manipulated to look older and more authentic but that typically don’t depict what the surrounding text suggests they do. The assessment, argued through the elliptical structure of his fiction, is that life is a set of interconnected, pointless, and depressing tangents that seem as if they might lead somewhere but don’t, or else lead inevitably to the one place you want desperately to avoid because from there you have nowhere else to go.

I like this. What I don’t like is actually reading the books, which have something posturing and needy about them, no matter how many memorable lines and images they turn up. Despite his love of Nabokov, Sebald wrote exclusively in his native language—having started publishing in his forties, he joked, he didn’t want to waste the time he had left—but he worked over his English versions closely, to the considerable frustration of his first translator, Michael Hulse; in English, each word seems to be chosen with tentative preciousness, though the commas are totally moreish. What Angier refers to as his “exquisite” style inspires in his fans a breathless, wide-eyed appreciation that does not waver in the face of comments such as “Reading The Rings of Saturn makes me feel as if someone is using tweezers to place cotton balls into my mouth one by one.” Express dissent and your interlocutors will look upon you with pity and condescension and, noticing that you like jokes, cite some great, ostensibly underacknowledged Sebaldian sense of humor. “But what about the lettuces?” they say, referring to a throwaway line in Austerlitz in which Jacques Austerlitz imagines lettuces dreaming in the garden. I am not exaggerating; while I was writing this article three people brought up the lettuces, and Angier also mentions them. They are cute and whimsical, and they remind us that we are destroying the world, which contains so many things that we do not and refuse to know. Almost surreal, his prose resembles a hotel described in The Emigrants: “The rooms are furnished in a most peculiar manner. One cannot say what period or part of the world one is in.”

His tendency to hide evidence that his books were written in the Eighties and Nineties is both part of his appeal and his weakest quality. Angier describes a deleted scene in the 2,200 pages of drafts Sebald composed while working on The Rings of Saturn: the narrator encounters a jogger wearing fancy shoes and a company T-shirt that reads get airborne. A chief steward on Virgin Atlantic, he intends to, in Angier’s paraphrase, “leave tracks that no one can see all around the world.” As Angier celebrated Sebald’s good decision to cut the scene—“realism and modernity,” she says, are “dangerous . . . to his particular art”—I thought of an essay by Patricia Lockwood about the work of Rachel Cusk, whose writing is so influenced by Sebald that you could swap their sentences without anyone noticing (though it would be appropriate if Cusk just lifted sentences from Sebald, as he often did from writers he admired, and whomever else he wanted). Lockwood writes of Cusk’s similarly despondent aversion to contemporary life: “Why must we live in these places? Why must these be our concerns? Why do I have to know what McDonald’s is?”

Because it is our job—without McDonald’s, we can see the writer’s point, but can’t quite make out its source. The Audis and BMWs that dominate the roads in the Allgäu contribute to an atmosphere of eerie, distorted perfection that is only augmented by the occasional whiffs of manure one gets while cruising along listening to a remix of the TikTok sea shanty playing on the radio in one’s sexy rented A3. Is this not sinister? The skies are utterly blue, the green of the fields in friendly competition with the green of the pines, and the shadows cast into the valleys formed by even the fake Alps powerful; it is as if nothing stands between you and the light, or you and the darkness, except the solar panels glinting off timber-frame houses. It turns out I quite enjoy driving on the autobahn, though parking at the Allgäu Stern Hotel and in the nearby ski resort town of Oberstdorf, where Sebald attended Gymnasium as a commuter student, was an absolute nightmare, at times unbelievably, upsettingly so, which is, in a roundabout way, part of his point.

In the final section of Vertigo, “Il ritorno in patria,” the narrator returns to W., the village where he grew up, after thirty years away. He finds it “modernised” but nevertheless ghostly, “more remote from me than any other place I could conceive of” despite seeing it constantly in “dreams and daydreams.” Today he would probably find it even more jarring, though Wertach is still so small that it does not have a train station, and its narrow empty streets create a shadowy creepiness that is not dispelled by the occasional tourists zipping through on electric bicycles. Beyond the Netto supermarket (which, like the Liverpool Street Station McDonald’s that is in fact briefly mentioned in Austerlitz, is illuminated by a “glaring light which . . . allowed not even the hint of a shadow and perpetuated the momentary terror of a lightning flash”), it is hard to find a place to buy a bottle of water, though behind the information center is a vending machine stocked with local cheeses. The house on Grüntenseestrasse where Sebald was born is adorned with a small plaque whose modesty is, according to one of Angier’s interviewees, “very Allgäu.”

To reach W., the narrator walks along a mostly downhill path through the mountains, beginning with a ski lift at the old customs post of Oberjoch, stopping to rest at an abandoned chapel and to meditate on Tiepolo, and ending about five hours later at this house. Today the Sebaldweg comes with its own brochure and is clearly marked for anyone who wants to undertake a pilgrimage, yet none of the tourists I saw seemed aware of its literary significance. (They were exclusively on bicycles, so I assumed they were not reading the commemorative stelae quoting passages from Vertigo stationed along the way.) Though an employee of the Wertach tourist bureau occasionally conducts guided walks, much of the path runs alongside the highway—indeed, free of holes—which was not there when Sebald himself was hiking through the November mist. I went alone, the way Sebald would have, but the weather was too nice for me to get in the mood.

The next day I drove to Kempten, which claims to be the oldest town in Germany, to meet with the founder of the Deutsche Sebald Gesellschaft, Ricardo Felberbaum, at a restaurant called Zum Stift. Felberbaum, who calls himself an “amateur” and a “dilettante,” is a buoyant, eager conversationalist with a day job as a gynecologist. When I contacted him to set up a meeting, he was out of town testifying as an expert witness in court.

Felberbaum first heard about Sebald when he moved from Bremen to Kempten in the early Aughts, and after he finally read the books, he was shocked to find that no one in the region knew who he was. “I went to one politician from the city and I told him, ‘Do you know this book?’ ” he said after I ordered my schnitzel. “No! No. This politician is somebody who was born here; he was here when Sebald had a certain kind of popularity. Abroad, he is a big shot! And he has an importance for other authors! I was really more than fascinated by this paradox, that in his native country he is almost forgotten.” An unfamiliar kind of fly, which had swarmed my windshield as soon as I parked down the street, crawled into his shirt pocket.

While Sebald is not exactly “forgotten” in Germany, it’s true that he hasn’t inspired what could be called a mania. In the Allgäu, Felberbaum thinks the issue is simple: people are “very addicted to sports.” As for the country as a whole, the most compelling reason is the one both Felberbaum and Angier mention: when Sebald was publishing his work, Germans had spent decades rebuilding their society and did not want to hear anything about World War II. Sebald’s focus on displaced Jews in his fiction highlighted the crimes of the Third Reich, but more controversially, On the Natural History of Destruction describes the unprecedented destruction wrought on German cities by the Allied bombings at the end of the war. Sebald argues that “the pre-conscious self-censorship” in response meant that

the sense of unparalleled national humiliation felt by millions in the last years of the war had never really found verbal expression, and that those directly affected by the experience neither shared it with each other nor passed it on to the next generation.

Having been a member of the Marcel Proust Gesellschaft for thirty-two years—it was founded by a urologist—Felberbaum knew something about running a literary organization, and although the Sebald Society has attracted only forty-one members since its official launch in November 2019, Felberbaum does not conceal his pride that they are besting the Kafka Society in membership. (The Kafka Society disagrees.) Their goal, he says, is simply to inspire more people to read Sebald, and to have his work taught in schools and stocked in bookstores. “I think you could go now through this biergarten and ask, ‘Kennen Sie Günter Grass?’ and almost everybody above twenty would say yes,” he said. “If you ask them, ‘Do you know Heinrich Böll?’ Some. If you ask, ‘Do you know Sebald?’ Almost nobody. And that’s why we started the society, because we would like to change that. Because I personally feel that he deserves it.”

I knew the feeling: the sense of injustice that comes with literary affinity, the idealistic conviction that if more people were to spend what little time they have reading your author, a different world might peek out from behind a door. Felberbaum is exactly the kind of person you want running your society if you’re a dead writer: he is animated almost entirely by a love of language and literature, and completely unconcerned with the writer’s life. As Angier demonstrates in Speak, Silence, Sebald’s work is especially slippery when it comes to biographical readings, though she tries, apparently animated by a similar feeling of injustice and conviction that she cannot temper, even when chilling out would better honor her author. Sebald’s habit of lying to interviewers—including, Angier gamely admits, her—was one difficulty; another was that he often lied to friends, who say he was charming but always reserved and sensitive, and often alone. After he died, many of his closest relations were unwilling to speak to Angier, and others were bitter, or at least ambivalent, about having had their lives mined and warped for his fiction. Because his widow has decided to keep their family life private, Angier could not quote from certain sources, and Ute Sebald’s name does not appear in the text at all; one only has distant memories of “his wife” and daughter when, near the end of the biography, Angier describes Sebald’s more-than-friendship with a woman from his past, Marie.

Instead of giving up—or writing a shorter biography—Angier figures this is appropriate for Sebald, whose work examines “the fallibility of memory, the death or disappearance of witnesses, the dubious role of the narrator.” As if hoping to prove that she has done a lot of research, she spends pages and pages detailing the various possible influences for Sebald’s fictional characters; the result is often a deeply confusing timeline, ominously foreshadowed leads that end up going nowhere (Sebaldian), and the conclusion that, like most fictional characters, his were composites. She also includes armchair psychologizing by people not particularly close to Sebald, admitting their gossip is unprovable but allowing nevertheless that it seems “deeply true.” At one point a woman who had an unrequited crush on Sebald in high school tells Angier that, based on her own experience of abuse, she believes Sebald had a “sexual wound”; in response, Angier takes a few downplayed examples from his fiction to infer that this wound was likely his fear of harboring homosexual desire. To support this claim she directs us to a photo showing how good-looking he was as a teenager and notes, “It’s hard to imagine that he didn’t attract looks from men as well as women.” What’s more, in order to establish his shifting, exile’s nature, Angier refers to Sebald by his various nicknames, so we are treated to a thankfully brief section in which we know him by what his university friends allegedly called him: Cocky.

From the beginning, it is difficult to trust much of what Angier says, and her kitschy style made me long for Sebald’s Gothic melodrama, and want to defend him from her misguided approach. Having already read much of the book by the time I met with Felberbaum, I felt a little sad for him, knowing that the first major biography of his author was so lacking, though I knew he wouldn’t really care. The most beautiful aspects of Sebald’s work have little to do with his enigmatic scene-stealing alter ego and the tricks he plays on anyone searching for autobiography; his great strength lies in the conventional narrative pleasures he offers with sensitivity, texture, and emotion, allowing subtle details to accrue so patiently that the realization, when it comes, feels like memory. Ambros Adelwarth, in The Emigrants, has a relationship with his wealthy employer that is only made clear in a single line taken from a diary at the end of the story, after both parties have already died: “Cosmo, curled up slightly, was sleeping at my side.” Jacques Austerlitz, though he grew up in Wales, speaks English so anxiously that “you could see the white of his knuckles beneath the skin.”

That this is not what drives Sebald’s influence does seem unusual. In his 2001 review of Austerlitz, Michael Hofmann wrote that it was startling that “books without much pretence of character or action, but where the role of story is taken by thought or reading—or even more starkly, by the memory of thought or reading—could catch on at all.” But in surveying his contemporary influence, I don’t know if it’s so surprising. Denialism about the existence of McDonald’s surely endears many readers to him, but Sebald represents something deeper about the postmodern intellectual situation. He formally captures the experience of the academic observer, the reader, the writer, the figure who is often in proximity to history, deeply aware of being trapped or “complicit” but who, rather than being directly affected, experiences it through stories, images, and research. Unlike contemporary novels, such as Jenny Offill’s Weather or Kate Zambreno’s Drifts, that depict this figure as almost circumscribed by their knowledge, engaged in a fraught search for a tidbit that will assuage, or at least relate to, a personal crisis that is ultimately the core of the narrative, Sebald represents the scholarly existence as vital; the research produces the meaning of the fictions, which, lacking a central focus, become testaments to the possibilities and the limitations of the work of art, to what it can and can’t achieve. This is not a criticism; it is, like McDonald’s, simply how it is.

It’s often said that Sebald’s work haunts, and is haunted. Do I like this? Not really, no. At times the gloom approaches parody—towns tend to be eerily abandoned, landscapes are shrouded in fog; even a passing car can’t escape without becoming “the last of an amphibian species close to extinction, retreating now to the deeper waters.” In projecting a ridiculous gravitas onto modern life, he might effectively emphasize its absence, but he often literalizes the metaphor in a way that diminishes its poignancy; reading Sebald, one can forget that death entails loss as well as the memory of what is gone. I wonder if I could somehow blame him for the number of people who seem to actually believe in ghosts.

But sometimes he has a point. One morning back in Berlin, I was sitting outside a bakery on Pannierstrasse, reading my friend’s beloved copy of The Rings of Saturn, when a small, elderly woman with hair dyed the purple of a red onion seemed to appear out of thin air. Exuding a genuine happiness, she greeted the owner of a burger restaurant playing house music through its open windows, sat down beside me, and opened a copy of the B.Z. newspaper.

In Vertigo, the narrator sees Dante walking in Vienna; in The Rings of Saturn, Catherine of Siena appears in post-reunification Kreuzberg. Who could this be? The B.Z. did not hold her attention for very long. Hildegard von Bingen? Ingeborg Bachmann? Maybe Julian of Norwich, who hails from Sebald territory and is improbably having a cultural moment?

Whoever she was, she soon struck up a conversation with me in a combination of Deutschkurs German and slow but equally perfect English. She hated the graffiti on the facade of this building. It used to be so beautiful.

I didn’t know how to respond—I liked the graffiti, but felt it would be insensitive to say so. I nodded stupidly, and within a few moments she was on to something else, suddenly thrilled by the fact that I was reading. In her apartment, just upstairs, were hundreds of books, she said, belonging to her husband, who I sensed was no longer with us. What was I reading? Sebald, I told her, and then the question came to me. Kennen Sie Sebald?

I was so hopeful, but I already knew the answer. No, she said, and when I told her, needing something to say, that he was from the Allgäu, her face lit up. She asked me if I liked reading, and I said that it was complicated, but yes, in general, I did.

I don’t, she replied immediately, scrunching up her face and shaking her head. My husband, he was the reader. She paused and looked at the graffiti she hated. I don’t like reading, she said again, putting her hands near her chest and frowning. It disturbs the quiet of my soul.

Soon after, I stood up and left. Walking across the Landwehr Canal, I parsed the possible implications of this comment: a funny example of a romantic German temperament; an unorthodox testament to the value of literature; a dark example of a dark German temperament. Regardless, I could no longer deny what was happening. There it was, the respectful difference of opinion, smirking at me from beneath his famous white walrus mustache. Touché, Cocky, I thought as I went. Touché.