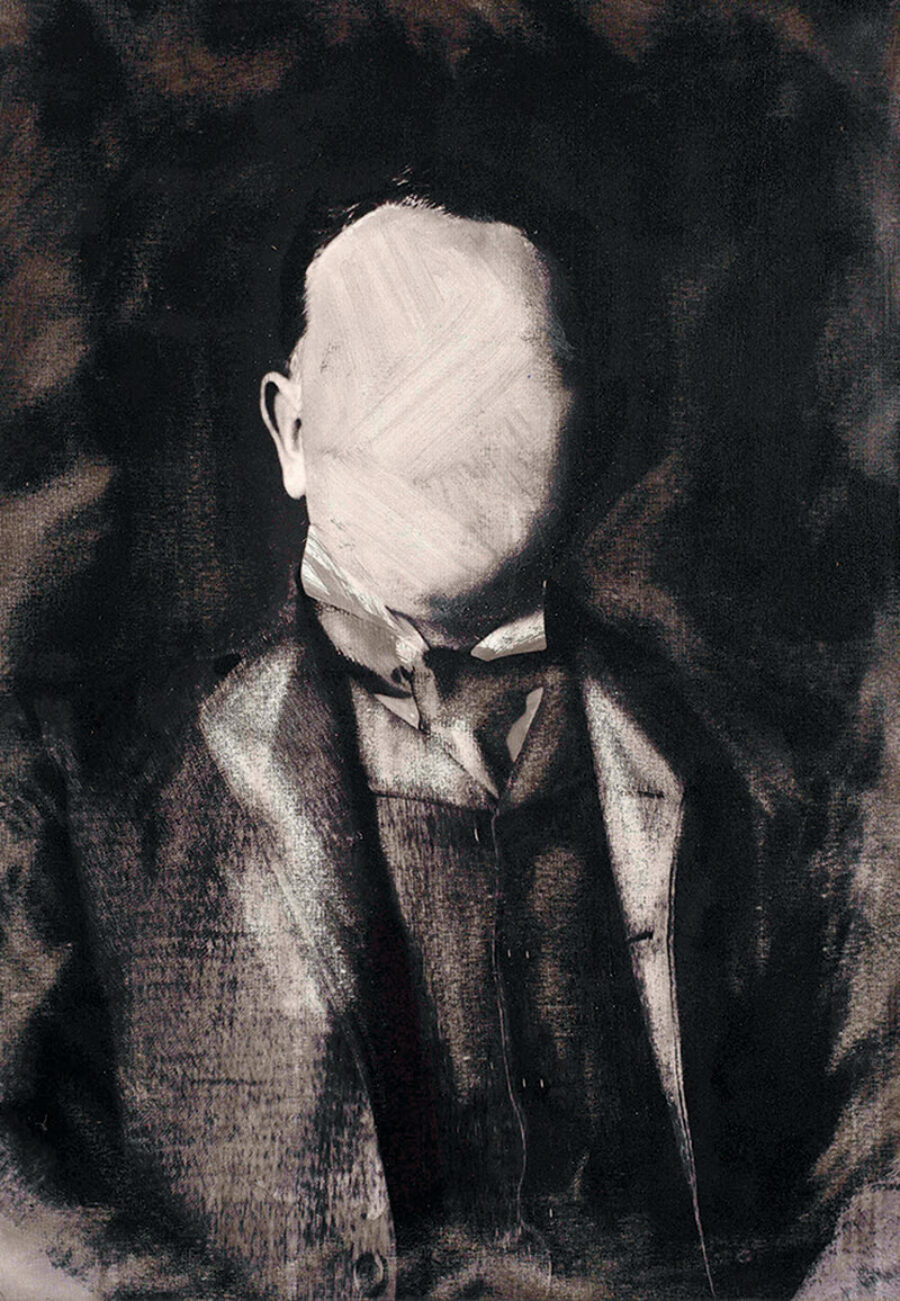

CJR, a mixed-media artwork by Mikhael Subotzky. Courtesy the artist and Goodman Gallery, Cape Town, South Africa

The nose disappeared from Cecil Rhodes’s face in September 2015. It was sliced off the bronze bust in the Rhodes Memorial on the slopes of Table Mountain. The plinth below was spray-painted: the master’s nose betrays him. Since then, the appendage has been at large. Was it stashed at the back of some cupboard or put to use as a paperweight? Did it go underground at a safe house, or was it ironically mounted on the wall by student comrades? Maybe it fled to New Zealand, trying to shuck off its colonial past and live in peace.

I work at the university just downslope from the memorial, and around the time of the disappearance, I was teaching Nikolai Gogol’s 1836 story “The Nose.” In it, the nose of a St. Petersburg bureaucrat, Major Kovalyov, vanishes under mysterious circumstances. He wakes up to find a blankness, “quite flat, just like a freshly cooked pancake,” in the middle of his face. We follow this hapless and petty man as he tries to find and confront his nose, which has taken on a life of its own. It is gallivanting round town, wearing a uniform of higher rank than the major, disowning him at every opportunity.

“Imagine what it’s like being without such a conspicuous part of your anatomy!” says Kovalyov as he tries to place an advertisement for his missing organ in the papers. When he finds it at Kazan Cathedral, we read: “The nose’s face was completely hidden by the high collar and it was praying with an expression of profound piety.” Censors forced Gogol to change the cathedral to a shopping arcade, on grounds of blasphemy—an example of how the story can co-opt any reader into its ridiculous universe. “Whatever you may say, these things do happen in this world,” the narrator reflects. “Rarely, I admit, but they do happen.”

So when Rhodes’s nose vanished, I felt intrigued and somehow implicated. I admired the gesture. Each year, as I taught the Gogol again, I was reminded of the unsolved mystery, and would ask for information at the end of lectures, promising to protect my sources. I dreamed of holding that bronze nodule in the palm of my hand. I wondered where it had been and what its adventures might reveal. At a time when political and cultural debates seemed so fraught, I wanted to understand this more cryptic element of the decolonization process.

In South Africa, the first semester starts in February: high summer, the dry season, fire season. I would be standing up in front of Literature 101 on the hottest day of the year, which often coincided with the opening of parliament. Rhodes left his nearby Cape Dutch mansion to future heads of state, and the highway below campus would be sealed off so that the president could make his way into town to deliver the state of the nation address, causing mayhem during Cape Town’s already chaotic rush hour. With the heat, the traffic, the army, the helicopters rattling overhead, the evidence of corruption stacking up, the Rhodes Must Fall protests brewing, with crowds of students demanding free, decolonized education—things had a manic feel, as if the city, the country, the whole world were fraying a little at the edges.

The wind worked on your nerves, kicking up dust on the dry slopes and turning small mountain fires into epic blazes. I often worried that a fire would sweep down from the slopes above the Rhodes Memorial and engulf the university—and then one day it did, just about. I’m writing up this investigation—which is a convoluted one, please stay with me—opposite a charred library, with a view of blackened cypresses outside my office window. They went up like Roman candles, ignited by flying embers, as did the pine trees Rhodes had planted. The literature department has been locked down for two years, and I’m beginning to wonder whether I’ll ever give an actual lecture again.

After several years of asking, I finally got a tip from a student. She said she knew someone who knew someone who had removed Rhodes’s nose. Not only that: this person kept on removing it whenever a replacement was stuck on by an organization called the Friends of Rhodes Memorial. There was a kind of arms race in progress.

“So apparently he has a whole collection of noses,” she told me. “His name is Josh.”

He’d been at a homeless shelter—that’s all she knew. There was a police docket open and her source was nervous, wouldn’t say more. But apparently some of the noses were just lying around in the shelter, next to the toaster.

Josh. It didn’t sound particularly pan-African, Azanian, or decolonial. But then again, you never could tell. So much had been written about Rhodes—his statues, his crimes, his legacy. But in the world of the nose, I came to realize, things were never quite what they seemed.

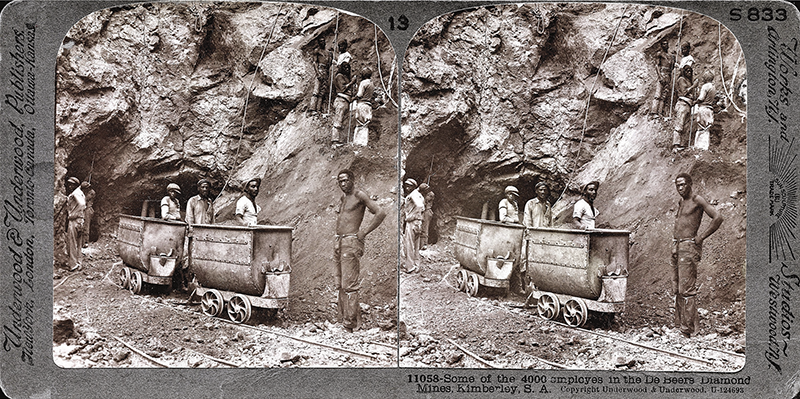

Born in 1853, Cecil John Rhodes was an English vicar’s son who first came to southern Africa, most say, for health reasons. In the 1870s, he made a fortune in the Kimberley diamond mines, going on to become one of the richest men in the world through his De Beers corporation. He went into politics, using his wealth and influence to further the cause of British imperialism, dreaming of ways to extend empire wherever possible. (Or even where not possible: “I would annex the planets if I could,” he once said. “I often think of that. It makes me sad to see them so clear and yet so far.”)

By the 1890s, Rhodes was at the height of his power: prime minister of the Cape Colony, with his British South Africa Company pursuing its interests across a huge swath of the continent, making war and signing treaties north of the Limpopo River, displacing and dispossessing the inhabitants of what is now Zimbabwe and Zambia. “The whole South African world seemed to stand in a kind of shuddering awe of him, friend and enemy alike,” wrote Mark Twain when he visited in 1896. “It was as if he were deputy-God on the one side, deputy-Satan on the other, proprietor of the people, able to make them or ruin them by his breath, worshiped by many, hated by many.”

But even Twain’s account of how Rhodes divided opinion divides opinion among his biographers (thirty-three and counting). While the hagiographers regard Rhodes with cultish fascination, the skeptics wonder how it was that someone so obsessed with greatness was really, in the words of one biographer, “a rather mediocre person.” He didn’t quite seem to fit his own ideal of a rugged Anglo-Saxon empire builder. The first thing many people were struck by when meeting the self-styled colossus was his querulous, high-pitched voice, combined with a casual sense of style. He preferred floppy hats and a shabby tweed suit to smart clothes, and men to women, so that a retinue of male valets and secretaries—“Rhodes’s lambs”—ensured that he looked presentable for important engagements. He kept a collection of stone phalluses from ancient African sites in his mansion at Groote Schuur, where he also had a big granite bathtub of Roman stature—so big that the granite drained out the heat, making it impossible to enjoy a warm bath. No matter. Rhodes the financier, fruit farmer, empire builder, conservationist, white supremacist, and warmonger preferred cold, manly baths—of course he did.

“Mister Rhodes,” a photograph by John Nankin of his installation at the One City, Many Cultures Festival, in Cape Town, 1999 © The artist

Why do I know all this? Because while I was doing a PhD on the literary history of Cape Town, I got side-tracked by the cautionary tale of Rudyard Kipling, who spent many summers on these slopes as Rhodes’s pet writer-in-residence and imperial PR man.

Along with the Roman lion cages, Mediterranean stone pines, English songbirds, summer houses, and zebra paddocks that make the landscape around the University of Cape Town such a bizarre imperial assortment, Rhodes also installed a cottage in the woods for poets and artists so that they could draw inspiration from the mountain. In this cottage, Kipling read the Just So Stories to his kids, but his writing for grown-ups took a drastic downturn. He became a fervid champion of the South African War, putting Rhodes on a pedestal as a British hero with an almost divine right to oversee the development of southern Africa (even referring to Him with the capital usually reserved for deities). This is why statues of Rhodes in Cape Town tend to come paired with lines of bad poetry by Kipling.

The vandalized bust on Table Mountain is one of several Rhodes statues in the city. There was one in the middle of campus (Rhodes sitting like Rodin’s Thinker) until it was removed during the Rhodes Must Fall protests of 2015. There is another in the city center: Rhodes striding amid the trees, museums, and pigeons. He raises a vaguely Fascist arm, more Mussolini than Hitler. The list of tributes goes on: Rhodes Avenue, Rhodes Drive, Mount Rhodes, not to mention Mandela Rhodes Place. You can’t move a meter without running into him.

All the statues have long histories of alteration, both authorized and not. On Heritage Day in 1999, contemporary artists were allowed to creatively deface public memorials. The Rhodes Memorial lions found themselves caged under a banner that read from rape to curio (a riff on Rhodes’s obsession with building a railway that might run from “Cape to Cairo”). The statue in Company Gardens was strung with brick-weighted ropes: a kind of ghost image, the artist explained, of the mine riggings in Kimberley.

The Rhodes Memorial bust has been repeatedly daubed, spattered, and even necklaced—when a tire full of gasoline is placed round someone’s neck and set alight, a way of rooting out suspected informers that was used during the Eighties, as the anti-apartheid struggle reached its climax. During my time on campus, I had seen the sitting Rhodes wearing traffic-cone hats, wrapped in black trash bags, and swaddled in green fabric. This last is a reference to Mgcineni Noki, also known as the Man in the Green Blanket. Thirty-year-old Noki was the leader of the striking miners who were shot down by police at Lonmin’s Marikana platinum mine in 2012.

De Beers diamond mining in Kimberley, circa 1900. Courtesy Mindat.org/Underwood & Underwood

In March 2015, the statue was pelted with shit that had been brought in from Khayelitsha, where thousands of residents were still using bucket toilets. When the Rhodes Must Fall movement began making international headlines, the statue was removed from its prime position in the center of campus. Felling that Rhodes, up there on his plinth like a sitting duck, was a fairly simple process, technically speaking. He was unbolted from the platform and hoisted up with a crane, not so much falling as ascending or levitating. It was an uncanny thing to see: something that had been so still, such a fixture for so long, suddenly beginning to move, wobbling in the harness of a crane. There is an iconic image of the moment, in which the performance artist Sethembile Msezane seems to be lifting him up with her feathered wings. She turns her back on History while everyone else is saluting it with their smartphones. Rhodes was lowered onto a flatbed truck and then raced down the highway to a secret location, the empire builder now in the position of day laborer. A gray box was placed over the plinth and that was that.

But the Rhodes Memorial farther up the slopes is a different proposition for the aspiring Fallist. It’s a big, hulking acropolis: part-Greek, part-Roman, part-Egyptian, with a touch of Nuremberg. You approach the inner sanctum via granite steps (one for each year of Rhodes’s life), flanked by bronze lions with shiny rumps from all the kids riding on them. The steps and pillars make it a popular backdrop for wedding and birthday pictures. On any given Sunday, people will be queueing between the columns with foil balloons.

And there he sits, the archimperialist. Or rather slouches, leaning on his arm, with a masklike face and cleft chin. the immense and brooding spirit still shall quicken and control, reads the inscription by Kipling. living he was the land and dead his soul shall be her soul. Perhaps there’s a little sneer of cold command, but mainly he looks bored and slightly bloated, gazing out “across the lands he’d won,” the poem continues, “the granite of the Ancient North, great spaces washed with sun.” Some two thousand kilometers to the north are the granitic domes of the Matobo Hills in Zimbabwe, where Rhodes is buried—and where loyalists of Robert Mugabe’s ZANU-PF periodically threatened to dig up his bones, whenever some distraction was needed from the tanking economy or electoral gains by the opposition.

Rhodes died of a bad heart in 1902, murmuring his famous last words: “So little done, so much to do.” It was often said to be heart trouble that made him come to southern Africa in the first place. His sense that he didn’t have long to live urged on his feverish imperial dreaming, his obsession with legacy, secret societies, scholarships—a desire to keep shaping the world from beyond the grave. “In its own way, Rhodes’s heart was almost as significant an organ as Cleopatra’s nose,” wrote the biographer William Plomer (not realizing that one day the reverse would also be true): “Had it been weaker—or stronger—the whole aspect of Africa would have been altered.”

The Rhodes Memorial, in other words, is not of the cheapskate, Soviet variety. It’s not like the Lenins and Stalins now put out to pasture in Memento Park. Nor is this a Saddam Hussein or a Confederate general who can be hooked up to a truck and bent to the ground like a toy. This is the British Empire in the final flush of its power, and the granite temple will probably be, like Abu Simbel, the last thing standing around here. Removing that nose must have required a serious power tool. It was sliced clean off, leaving a patch of bright, untarnished metal.

Last summer, during the hard pandemic lockdown, the memorial bust was beheaded. Someone had accessed the padlocked Rhodes Estate at night, during a huge winter storm—perhaps to disguise the sound of a portable angle grinder. That’s what had been used in 2016 on the striding Rhodes in the city center. Operating in broad daylight, a group in orange vests had posed as construction workers. They put caution tape around the statue and got a quarter of the way through its lower right leg, leaving a nasty gash in the heel.

But portable angle grinding technology continues to improve. In the lockdown operation, about 70 percent of Rhodes’s head was ground off (starting just above the jawline), then rolled across the plinth and dropped to the ground, where it left a dent in the pine needles, evidently too heavy to move any farther.

It was found “in low scrub,” according to press reports. A picture showed a noseless severed head resting in the fynbos, so presumably the grinder got away with that keepsake at least. This was the difference between Gogol’s nineteenth-century tale and my more postmodern predicament: here the nose was continually respawning.

After some tense diplomatic negotiations between South African National Parks, Heritage Western Cape, and the city government, the head was handed over to the Friends of Rhodes Memorial, which stated that they wanted to prevent it from falling into the hands of some sort of government-sponsored “theme park.” The Friends then repaired, reaffixed, and fortified the head. This involved filling it with industrial cement, making 3D-scanned replicas for future reference, and (so they claimed) installing a GPS tracker inside.

This cat-and-mouse game had become, by then, part of a much larger phenomenon. In the wake of Rhodes Must Fall and Black Lives Matter, anti-colonial statue protests—and counter-protests—had gone global. In Pretoria’s Church Square, a top-hatted Paul Kruger (once seen by some as a hero for standing up to Rhodes and the British Empire) had been spattered with paint by Economic Freedom Fighters (EFF)—and then surrounded by khaki-wearing defenders; black steel fencing was later installed. “It is a shame that these dark figures of our ugly past continue to haunt us as we walk and drive on our roads,” said the EFF counselor Moafrika Mabogwana. The party called for Kruger to be replaced with Winnie Mandela.

In 2014, a nine-meter statue of Nelson Mandela throwing his arms wide in front of Pretoria’s Union Buildings was found to have a tiny bronze rabbit in its ear. It was a secret sign-off from the sculptors that did not go over well with the Department of Arts and Culture. “We don’t think it’s appropriate,” said spokesman Mogomotsi Mogodiri, “because Nelson Mandela never had a rabbit in his ear.” The rabbit was removed and given to Dali Tambo, son of Oliver Tambo, leader of the African National Congress in exile. Tambo the younger led the company that built the statue, and had also been the driving force behind the Long March to Freedom, a massive installation of one hundred figures from southern African history, all walking toward liberation, that was first exhibited on the outskirts of Pretoria. Billed as “the world’s greatest exhibition in bronze,” the Long March had recently arrived in Cape Town, installed on a strip of Astroturf between a faux-Tuscan shopping mall and the N1 highway.

Nelson and Winnie Mandela are at the front, where you enter, with Oliver and Adelaide Tambo close by. Both couples raise their hands, striding into a future that is fast receding. The march ends with Mandela walking out of prison in 1990, poised to lead the country to democracy four years later. Behind him, a parade of activists, organizers, and freedom fighters stretch back into history. There are Cuban and Communist fatigues (Chris Hani, Samora Machel), lawyerly suits (Govan Mbeki, Bram Fischer), Nehru jackets (Chief Albert Luthuli), then the waistcoats of the early twentieth century (John Dube, Walter Rubusana). There was Miriam Makeba with a microphone and Solomon Mahlangu with a machine gun. There was Solomon Plaatje on his bicycle, collecting testimony from those displaced by the Natives Land Act of 1913. Critics had said that the Long March was kitsch, triumphalist, or just plain weird. But I found it affecting, walking backward through the spaced figures, feeling that huge historical tide running against injustice.

The Long March, presumably, was the ANC-aligned “theme park” that the Friends of Rhodes Memorial wanted to keep his severed head away from. But who were these Friends exactly? Their website had photos of regular “flash mops” that were held whenever the memorial’s central alcove was spray-painted or set on fire. On Heritage Day they would be out in force, mopping away. Elsewhere on the website was a photo of a chameleon: a beautiful blue-green creature with sad eyes and a curly tail. The accompanying post read: rhodes statue protest—is to save the cape dwarf chameleon not rmf as imagined.

The Friends, that is, claimed the defacements were not political, but actually stemmed from a campaign on behalf of Cape dwarf chameleons. These creatures had been threatened by the introduction of a mechanized, shaker-type harvester on fruit farms. The man believed to be behind the vandalism, the Friends claimed, had a record of mental illness and was a patient at Valkenberg Psychiatric Hospital.

It sounded ridiculous, like pure conspiracy. But it was stirring a memory.

The removal of the Cecil Rhodes statue on the University of Cape Town campus, 2015 © Roger Sedres/Alamy

Kabelo Sello Duiker was a beloved postapartheid novelist who took his own life at the age of thirty. In his 2001 magnum opus, The Quiet Violence of Dreams, the narrator, Tshepo, spends time in Valkenberg—for “cannabis induced psychosis,” say the doctors, but maybe just for absorbing some of the trauma and madness of the society around him. This is what the novel suggests, a wild and haunted book that is something of a cult favorite among younger South Africans.

In Valkenberg, Tshepo befriends a man named Matthew who is obsessed with: chameleons, with saving chameleons from the machines used to harvest grapes on vineyards. “Went on a rampage,” Tshepo tells his friend Mmabatho, “saying that these farmers should destroy the wine because it’s got chameleon blood.”

The character in Duiker’s novel is based on a real person, Matthew Louwrens, the same person that the Friends of Rhodes Memorial suspected of defacing the bust. Matt’s chameleon campaign had appeared in the papers at the turn of the millennium, and had even been the subject of a televised investigation. mental asylum is full of prophets, court told, read a local headline from the time:

The man accused of setting the chapel at Rhodes Memorial in Cape Town alight and vandalising the monument earlier this year has told the Wynberg magistrate’s court that there were many prophets in Valkenberg Hospital—a psychiatric institution. William Matthew Lourens [sic] said two men at the hospital believed they were Jesus Christ. He added: “In fact if Jesus were to grace us with his presence he would immediately be sent to a psychiatric institution.”

There were pictures of Matt in a magazine article about Valkenberg, bare-chested in one of the outdoor yards, flanked by guys in low-slung pants and gang tattoos. The pictures were, I noticed, taken by a friend of mine. I called him up, and he arranged a meeting with Matt at a bar in the Observatory, a neighborhood that everyone calls Obz.

How to describe Obz? “Oh, that’s easy,” said a visiting American friend as soon as he saw it. “This is the Bob Marley neighborhood. Every city has one.” The main drag is filled with Rasta murals, herbalists, and health food shops. But on the other side of the Liesbeek River, the suburb becomes something else, something starker. Amid wetlands and wind-bent trees are the nineteenth-century telescopes that gave the suburb its name. On one side of the old observatory is a driving range; on the other is Valkenberg. Most wards look like nondescript houses or classrooms, painted mustard yellow. But set apart across the water is a building surrounded by high walls and coils of razor wire.

Matt had done time in the mythic Ward 20, a maximum-security portion of the hospital for patients with criminal records. He’d then lived nearby at Oude Molen, an unkempt urban parkland where he’d established a gardening program to help patients reintegrate into daily life. You can reach it if you carry on past the wards, away from the mountain, through a patchwork of small organic farms, scrapyards, and squat buildings.

I used to wander there when I lived in Obz. There was something exhilaratingly unresolved about the place: derelict wards and runner beans barely holding on against the wind, the scrap collectors in their horse-drawn carts, Devil’s Peak in the distance. The peak would split the sun’s rays like a huge dark prism looming over the city. “It was not his fault, poor fellow, that he called a high hill somewhere in South Africa ‘his church,’ ” wrote G. K. Chesterton about Rhodes. “It was not his fault, I mean, that he could not see that a church all to oneself is not a church at all. It is a madman’s cell.”

On the phone Matt had seemed a bit wary: Was this some academic bullshit? He’d had university types bugging him before. Absolutely not, I assured him. And then I reminisced, when we met, about my years of walking around Obz in Guatemalan shirts and no shoes, lodging with a self-described white sangoma (traditional healer) named Edna.

She specialized in doing “geoharmonic clearings” of public spaces and healing events that were generally aligned with solstices and solar equinoxes. This was in collaboration with a boyfriend who believed that the whole of Hoerikwaggo (“Sea Mountain”: the indigenous name for Table Mountain) was an ancient Khoisan observatory, somehow linked to the pyramids. Edna and her geo-astrologer had done psychic clearances on car parks built over cemeteries and boutique hotels built over slave burials. But they turned down Rhodes’s old zoo—an eerie, overgrown place on the edge of campus where students go to smoke spliffs among the lion cages. The energy there, Edna said, was just “too heavy.” Like the whole Obz vegan community at the time, she was freaked out by the culling of tahrs on the mountain slopes. The tahr was a Himalayan goat that had escaped from Rhodes’s menagerie and colonized Table Mountain, making life hard for local klipspringer populations. Rangers had been poison-darting tahrs from helicopters, but even today there are rumors of holdouts and survivors, like the myth of the yeti, with blurry pics of goats on isolated crags.

“That zoo is Masonic shit,” said Matt, nodding and smoking vigorously. “Runes, Freemason symbols. Demonic.” That was partly why he torched the chapel: “It was an exorcism.”

If you had to pick someone out of a lineup for anti-imperial arson, Matt might not be your first choice. He was a tough-looking farm boy from Kokstad with plenty of laughter in his eyes. Back in the Eastern Cape, he’d also begun training to become a traditional healer. This was a calling where hearing voices in your head—or your stomach—didn’t necessarily mean you had schizophrenia. It might be amafufunyana, as the people in Xhosaland said, or ukuthwasa: the ancestors talking to you, calling to you, asking you to take action.

“I shook that vine,” Matt said, pulling hard on his cigarette. “I shook that beanstalk and all kinds of things came down on me. Heavy things, hectic things.”

He opened a folder and began taking out well-thumbed letters, court documents, press clippings. A front-page picture in the Cape Times documented his handiwork: Rhodes daubed in bloody enamel. There was mm at the top (for mass murderer, he said) and viva below one of the lions. There were pictures of him wearing a tweed flat cap and holding up dead chameleons, handfuls of them, in front of vineyards.

“Good looking, hey?”

This was a man in the prime of his life: photogenic, charismatic, and fired up by a moral crusade. It was the late Nineties and he’d been working in the Stellenbosch area, living on a vineyard on an island in a lake. Mechanical harvesters were being introduced for the first time, partly, he explained, as a way to break strike action in the wine region. The same industry responsible for creating an alcoholic society via the “dop” system (i.e., paying wages partly in alcohol) was now reducing its labor requirements. And doing nothing, Matt said, flushing red, to remedy the fact that South Africa had the highest rate of fetal alcohol syndrome in the world.

Our table was now covered with handwritten letters, pages and pages of them. “These machines use vibration to harvest grapes and can harvest up to ten tons an hour,” he wrote to South Africa’s congress of trade unions: “Unfortunately the machine does not have eyes and cannot see that the grapes are not alone.” Not only chameleons were affected, he’d pointed out to the South African Broadcasting Corporation, “but also skinks, snails, snakes, locusts, ladybirds, and mice.” The Cape dwarf chameleon was, he reminded the director of public prosecutions, an endangered species that was illegal to transport without a permit. All parties were referred to Phillip Kubukeli, president of the Western Cape Traditional Doctors, Herbalists, and Spiritual Healers Association, who had ruled that wine containing chameleons is poisonous.

Was his Rhodes protest related to the chameleon campaign? Not really, Matt said. So then why were they linked in the press? I pointed to a clipping: sour grapes led man to paint rhodes red.

“I probably told them that,” Matt said, smiling his trickster smile. “It was a hectic time in my life. Things were linking, overlapping. My wife divorced me, my family had me committed. To tell you the truth, I was also smoking a lot of dagga.”

His family put him in a hospital in Pietermaritzburg, where he was diagnosed with schizophrenia—a diagnosis that he later contested in court. This was where he had gotten to know Sello Duiker.

“Different mental institution. Fuck, I know them all,” Matt said. “Anyway, Stellenbosch University got big agri and its scientists to refute me. They said the machines only shake at 2.5 newtons, or whatever it was, and the chameleons can hold on for 3.5 newtons. There was a Carte Blanche episode on it. They said I was sensationalist.”

He held up a picture of himself looking into the eyes of a shriveled chameleon. I had the sense that he had been carrying around this folder for years, its petitions and court documents the mementos of a blazingly vivid youth. As we emptied it out, there were also nude photographs of old girlfriends and—this took even him by surprise—a close-up of a penis being gripped in barbecue tongs. “These photos haven’t been properly sorted,” he admitted.

Because of Matt’s direct action—chaining himself to harvesters, smashing bottles of offending vintages in pubs—he had been arrested and roughed up by the police. But then he was deemed unfit to stand trial. Nonetheless, even as the case was being thrown out, he had conducted his own defense and delivered a denunciation of Rhodes. “And I got a standing ovation,” he said.

Matt messaged me often after our meeting, sometimes up to thirty times a day. He was, by his own admission, having an episode. But new things had come to light, new intel on political assassinations and other conspiracies—it was never who you thought it was. To catch a nose I should keep my mind open, he said, open to things beyond the rational.

In South African mythology, the tokoloshe is a malicious imp that preys on its victims at night. Tabloids are always claiming to have caught one on camera making someone its sex slave or wreaking havoc among churchgoers.

In Cape Town, an anonymous cabal of graffiti artists had taken its name from this anarchic creature. The Tokolos Stencil Collective went around spraying non-poor only in trendy Woodstock and designated mugging area on the Sea Point promenade. They stenciled gentrinaaiers, which means either “fucking gentrifiers,” “gentrifucks,” or “gentrifuckers.” Their stencil of Mgcineni Noki in his green blanket was everywhere: remember marikana.

In September 2015, the collective announced that it had received a pseudonymous email from someone called The Nose, alerting them that something had happened at the Rhodes Memorial. Was this a copycat artist wanting some affirmation? The email made a literary allusion: “We have stolen the nose of Rhodes at the memorial on the hill dedicated to this racist, thief, murderer and of course philanthropist,” it read. “The nose of Rhodes (Gogol) has left his face and developed a life of its own. It now goes on a journey. Where will the nose show up next? Time will tell.”

I added this new lead to the detective corkboard I had made, like the ones in serial-killer movies. The Rhodes bust with “that ridiculous blank space” at the center, strings and arrows radiating outward. To Kipling’s drawing for his kids of a crocodile pulling an elephant’s nose from the Limpopo River. To Rhodes’s bath and ancestral dildo collection. To chameleons and a dreadlocked K. Sello Duiker. Around the border danced various other noses: stage designs by the artist William Kentridge, for instance, for a production of Shostakovich’s 1928 opera based on Gogol’s tale. Kentridge had gone for a Socialist International aesthetic, so there were drawings and cutouts of Soviet noses riding horses and ascending monumental pedestals. They got around on Constructivist stilts, and even (in one etching) performed cunnilingus. Next to that I placed an article from the Daily Sun: tokoloshe blow job terror.

It was this new Gogol/Tokolos lead, I think, that proved crucial in my email courtship of the chairman of the Friends of Rhodes Memorial, which had been going on for months. If this was the man who had been methodically replacing Rhodes’s noses, I needed to speak to him. The chairman was clearly on the opposite end of the ideological spectrum from Matt and the Tokolos Stencil Collective. He was suspicious at first, wondering what my politics were, but I persevered, changing my colors as needed. Did I agree, the chairman asked, that the defacements were probably not linked to RMF or BLM—and were more likely a prank inspired by Gogol? When I emailed him about the allusion I had unearthed via the anonymous message to the collective, the chairman finally agreed to a meeting, and a handover.

“Drinks on me,” I emailed.

“Nose on me,” he shot back.

We met at a hotel bar in the no-man’s-land between Valkenberg and the N2 highway. Gabriel Brown is a tall, shambling man with an expressive face that would suit a comic actor. “First things first,” he said, removing a blue-green nose from his breast pocket and putting it on the table. “I’m not happy with the color, actually.”

I picked it up with a warm glow of achievement. My inquiries had finally yielded something concrete, something real: a fake plastic nose. Gabriel had arrived with several Shoprite bags full of models and replicas, which he laid out on the table between the bar snacks. There were the lions, the bust—meticulous 3D-printed plastic figurines—and then a much bigger nose, a massive hunk of cast resin that had been treated to look like weathered bronze.

This, Gabriel explained, was the master nose. What he had given me was a smaller, cheaper replica: the offcut that corresponded to the tip of the nose that had been repeatedly sliced off and replaced. The tip that I held in my hand was about human-size (if you were generously endowed). The master nose, which he kept on his side of the table, was superhuman.

When the nose first vanished in 2015, Gabriel said, it plunged him into a terrible depression. “I had to do something,” he said. “No one else was going to.”

He experimented with green Plasticine, then resin. But making it stick was the real challenge. He tried double-sided tape, various glues—but the nose kept falling off. Eventually he drilled a hole into the flat space to insert a stabilizing dowel.

“A black dust came out of the statue,” he said. “I thought: I’m the first person to inhale this for a hundred years, like Tutankhamun’s tomb. It was the greatest moment of my life.”

As Gabriel spoke, I realized I’d seen him before. He was the person who used to heckle Rhodes Must Fall rallies back in 2015. I’d seen people throw food at him, pull him out of venues, try to rough him up. When student cadres chanted “Rhodes must fall,” he would shout back, “Rhodes will rise again, Mugabe said so!” At one point he’d been dragged away to a waiting car, thinking it was all over, that his body would be found dumped in the Liesbeek. But it turned out they were undercover police officers.

“I think they saved my life,” he told me. “I was stupid, trying to go against that mob mentality. After that, I thought about how I could actually make a difference. I decided to look after the memorial instead, so that all kinds of people can enjoy it.”

The Friends of Rhodes Memorial was founded as a nonpartisan body, meant to break the postdecapitation deadlock between South African National Parks, controlled by the ANC, and the city authorities, which were in the hands of the Democratic Alliance, the opposition. The ANC and the DA were, as usual, playing political football with Rhodes’s eighty-kilogram head.

“I was the one who found it, actually,” Gabriel said. “It was there in the bushes, hollow like a big soup tureen. There was a trail across the flagstones, then a dent in the grass, and then a track into the bushes. He was lying there, like something out of classical mythology. I mean: What do you do when confronted with the head of a god?”

He paused for effect.

“I faltered. I’m a mere mortal. I should have taken it then, but I decided to come back with help the next day. But it was gone, dragged to the car park. Then it was weeks before Table Mountain National Park admitted to having it, even longer before they handed it over.”

He leaned closer.

“But I’ll tell you a secret: It’s not the real head. It’s also a copy. They wouldn’t give up the original. It’s still in some apparatchik’s filing cabinet. But who cares—authenticity doesn’t matter so much anymore.”

When I asked him whether there were any other Rhodes statues I didn’t know about, he bristled, suddenly suspicious. Why was I asking that? “I don’t know who you are,” he said. “I might be speaking to the enemy here.”

To calm his nerves I brought out my dissertation and showed him the picture of Rhodes’s tub.

“I simply must have a bath in that!” he said.

The Friends had, Gabriel admitted, attracted some strange bedfellows via their Facebook page. Some conceptual art student emailed about wanting to make an installation. He couldn’t remember the name: some breast-beating liberal, a white-guilt type. And then there were the evangelical Christians who helped with the flash mops, but who also liked to preach from the steps.

“Charismatic,” he said, looking into his beer. “But not very gay-friendly. American money, I think, with links to Trump and all that, Zionists, the Rapture. Once they even sprayed graffiti on the walls: Mount Sinai.”

So he was getting it from both sides, the radical left and the religious right?

“Yes, it does seem to attract oddballs. Like me.”

He finished his beer, smiled.

“And you.”

A few weeks later Gabriel sent an email saying that he was making another nose for me, a better one. Oh, and he’d remembered the name of that annoying art student—it was Josh.

The head from the Rhodes Memorial on Table Mountain. Courtesy Gabriel Brown, Friends of Rhodes Memorial

Had the nose been hiding in plain sight all along? On Josh’s Instagram was a Greek statue, rotating in digital space. On his website was a short film of the bust growing a shiny new nose, which hung there for a minute, pregnant with significance, then fell off. There was also a project in which the artist had made a virtual 3D model of his own flaccid penis. If I were an art critic, I might suggest that Josh’s work operated on a continuum, or dialectic, between hard and soft: an unresolved tension between (public) noselike rigidity and (private) penile slackness. “Dick pics are about ego and power,” he had written on his website. “How hard . . . can you get? What’s your capacity to penetrate?” Hard penises lent themselves to crude doodles and sculpture; soft penises were embarrassing, and lacked representation: “No one wants to speak about them. When shown on film, they’re shyly glanced at for only a second.”

I reached out, and he suggested that we meet in Paradise, a little urban parklet along the Liesbeek River. On the drive over, I felt anxious that he was going to be too cool for me, smarmy and supercilious. But Josh was nothing like that. The long-haired man who emerged from the dappled shade was gentle, soft-spoken, earnest. I got straight to the point and took out the blue-green nose. He smiled and nodded, as if he’d been expecting this: “I see he’s changed the color scheme a little.”

Josh said he had about seven or eight noses in his possession. But not the original, not the ur-Nose—he confessed that straightaway—and he had no idea who might have removed it. The Rhodes he’d first encountered was noseless, but when he returned to make a scan of the head for a 3D model, one of Gabriel’s replacements was attached. He’d felt upset. He thought the bust looked really interesting without a nose, beautiful even. Replacing the nose was like defacing an artwork, one that he wanted to restore to its original state. So he’d entered into a kind of—he paused for the right word—conversation with the person who’d been replacing it.

At first they were hard to remove, Josh went on, but now it was easier. He’d knocked one off the other day with a screwdriver. But it had bothered him, how long the whole thing had dragged on for, how determined the nose replacer was. That’s why he’d taken it further and gotten involved in the decapitation. This was a major operation involving three people, a cold chisel, a hacksaw, a crowbar, and an angle grinder. And the noise!

Telling the story in his soft voice, he sounded a little mystified at how he’d gotten himself into all this, even a little rueful. He’d arrived at Cape Town’s art school from Grahamstown, or Makhanda, rather, as an evangelical Christian, wanting to “make art for Jesus.” But doubts crept in. He’d since left the church, but still tried to serve in homeless shelters.

When I asked how he had found himself knocking off noses with screwdrivers, Josh didn’t have a direct answer. He didn’t know all that much about Rhodes, to be honest. But he’d never seen such extremes of rich and poor before—there just wasn’t that much wealth back home. He felt he had to do something, and Rhodes was the focus.

When they beheaded Rhodes on that stormy winter night, they noticed there was already a deep cut in the neck from a previous attempt. The original nose removal, Josh reckoned, was unpremeditated, opportunistic: “I think they just cut off what they could.”

Two days after I met Josh, the Rhodes Memorial exploded. Matt sent me a clip of fire sweeping down off the mountain and igniting the gas canisters of the tearoom: “Wasn’t me!”

Some blamed vagrants, others arson. Or else the colonialist pine trees Rhodes had planted, the alien invasives that burned so fiercely. Some cheered on the fire as it came down the slopes toward the university, fanned by a dry wind: Rhodes and his legacy would finally be cleansed. Of course, that granite temple couldn’t burn down, but the most beautiful reading room of the library could, and did. Blood-red flames, the African Studies collection reduced to ash, students in terror or heroically putting out burning palm trees—I followed it all online, right down to the meals abandoned in the tearoom, pictures of pickled fish left on plates.

It wasn’t really the time for this, he knew, but Josh sent me the longer edit of his film. On the bust of Rhodes, the nose slowly grows back, holds still, drops to the floor. Then another one grows, drops down the steps, and then another, faster and faster, becoming a torrent of shiny new noses, cascading down the steps, like you’d pulled some monumental slot machine and hit the jackpot.

“But the strangest, most incredible thing of all is that authors should write about such things,” says Gogol’s narrator toward the end of the story, admitting that his account doesn’t really add up:

That, I confess, is beyond my comprehension. It’s just . . . no, no, I don’t understand it at all! Firstly, it’s no use to the country whatsoever; secondly—but even then it’s no use either . . . I simply don’t know what one can make of it.

All I’d really uncovered, in the course of a five-year investigation, was a succession of charming oddballs. Josh, a lapsed evangelical with interesting things to say about slack penises. Matt and Gabriel, with their radically opposed ideas of how to go about being a white man in Africa. One who had tried to be a sangoma, traveled all over the continent, tried so passionately to indigenize himself. The other content to keep living in a Rhodesian fever dream, making the memorial nice for the procession of Muslim wedding parties that queued up there on weekends.

I had found a lot of noses, but not the original. I was disappointed but also relieved. Disappointed that I hadn’t found the ur-Nose, but relieved that the true perpetrator was still out there. That he might still be a prophet or madman, a homeless savant, a radicalized rough sleeper or whatever else I needed him to be. That he wasn’t an art student. That he, or she, might perhaps be reading this, and might one day provide me with an answer.