Illustration by Romy Blümel

An Errand

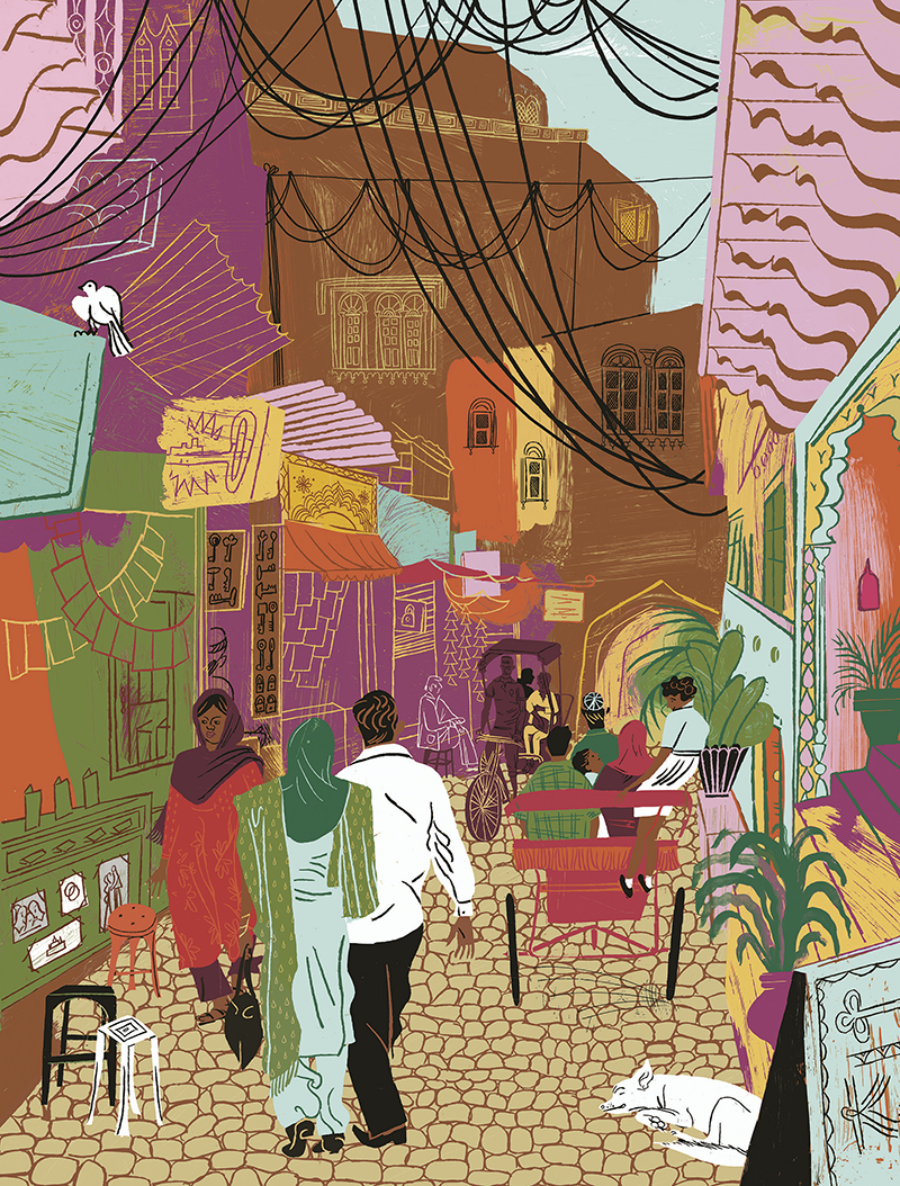

In Old Delhi, not far from Chandni Chowk, on roads plied only by cycle rickshaws and men and women on foot, there is a wonderful little set of alleyways that fork off from the already tight little streets.

It is here that my sister and I have come on an errand of the sort our parents now pretend to be too old to undertake, but which really it just amuses them to see the young busied with. And we complain, though we are happy enough to get out of the house and into the city.

Working our way in from the station, we pass the dusty bookshops whose vitrines are filled with old medical textbooks and adventure novels, and the shops of the lock sellers and key cutters, and not a few drunks asleep atop the gutters, and find ourselves in the alleys of the wedding stationers. There’s one in particular we’ve been recommended, who used to be connected somehow or other to the Nawab’s court when our grandfather was wazir-e-azam at Rampur, but his heavy wooden doors—not metal shutters, as you’d see elsewhere in the city these days—are closed with a slide bolt and a brass lock. There is no sign as to when he might reopen. In fact, though it’s a Tuesday, most of the wedding stationers appear to be closed, per some schedule unknown to us.

Before we can begin discussing whether we will bother to make the journey here again, another stationer, a few shops down, calls to us. This man, about fifty or sixty, in a white kurta and skullcap with henna in his beard, is seated on a high bank so that his legs are visible above the counter that faces the street.

We walk over and ask if he knows about the closure of his competitors, but he makes a noncommittal gesture.

My sister looks at me for permission, and I shrug.

“Do you have anything in a heavy cardstock, and that takes proper gilt lettering?” she asks.

The man shouts up to the loft into which a ladder disappears, and after a minute’s rummage some invisible hand tosses down bundles of fresh stock and a packet of sample invitations.

The samples are gaudy, clearly offprints of invitations from real weddings, and my sister and I are in an unspoken sympathy of offense at the sequins, borders, and loud scripts. But the plain stock is quite good, a lucky find. We sort through ten or twenty choices and ask after prices, then settle on the best one, which happily is among the least expensive, and give the stationer the particulars.

My sister hands him our written-out text, but he waves her off and asks that we dictate it to him.

“I can’t read anyone else’s writing,” he says, “or at least I can’t be held responsible for it.” Then he asks offhand when we’ll need it.

My sister tells him that the wedding is in mid-April, so two weeks from now at the latest.

“You must be Muslim,” he says.

We are not wholly surprised that he can tell, our salaams were genuine and casual, but why, we ask, does he ask?

“The astrologers have told the idol-worshippers”—our co-religionist here gives us a wink—“that April will be unlucky, so things have been dead slow. Only people of the Book are getting hitched in April.”

We don’t know why he is speaking under his breath in this area, which looks to be all either Muslims or stray dogs, but we lean in as if being told a secret.

I ask, in jest, whether any Jews or Christians are ordering invitations, but he ignores me.

“Anyway,” he says. “Please give me the names of the betrothed.”

“Mrs. S— Z— to Dr. A— A—,” says my sister.

“Slow down,” he says. “I want to make sure I’ve got that right. You said Mrs., yes? Mrs. for sure?”

“Yes,” my sister says, “it’s an elder relative of ours. She was married when she was very young, actually before I was born and when my brother would have been a baby, but her husband died in an accident.”

“Ah, God forgive us. No children of her own?” asks the stationer.

“No, none.”

“But she has found a doctor for a husband,” the man says confidently. “And perhaps he has children, grown like you and your brother?”

My sister nods.

“And they will give each other some comfort in their twilight years.”

My sister and I both say nothing. The stationer notes our distraction and asks whether we are worried about a match with so little at stake.

“Well,” says my sister. “It’s a troubling situation, really.”

“Why should it be so!” shouts the man, and his voice is so rich with concern that my sister tells him all.

“For years after our auntie’s first husband died, the family hoped she would remarry. She kept her looks for a good long time. Even today she’s rather beautiful, though I never know how to judge old people.

“Anyway, she would still get an offer here and there, even as she moved past a normal age for marriage. And so our family came to hope that her heart might have softened and healed, but at that very time a peculiar delusion fixed in her mind.”

My sister is using her chastest Urdu diction, and the stationer interrupts her with a playful “Vah! Vah!” I find myself a little jealous. He says he’s Lucknow born and bred and no Lakhnavi could speak any better.

“She had traveled to the Gulf countries some years ago and got it into her head that the son of a particular sheikh was in love with her. She never so much as met this man, but when she got back here she told our family about his great affection for her, though of course she couldn’t provide any evidence of it. Everyone thought she would eventually recover her senses since she was back in her own country. But if the affair was all in her imagination, why should distance disillusion her?

“She was sent to her aunt and uncle’s house in Kashmir that autumn, but neither did this do her any good. She claimed the leaves of the chinars that had fallen on the ground outside her window had been disturbed by the footsteps of the sheikh’s son as he watched her, when really it was nothing but the gardener, or the wind. If the milk in the pantry was low, it was because he had drunk it in the nighttime. If the autumn-blooming roses put on a good show, it was because he had fed them egg shells and molasses. If the post was delayed, it was because he was jealously reading the letters for evidence of another suitor.

“This bent of mind has remained the case, as far as we know. But she has learned not to speak of it. Ten years ago, she nearly yielded to the family’s pleas to remarry, when a good man, a foreigner—”

“Swiss, I think?” I say.

“—who had a tea plantation in the east, made a proposal, but around the same time she had the misfortune to make the acquaintance of some charlatan, a supposed swami, who read her sorrows and her hopes too well and told her not to commit to the union, that someone better would be along soon, someone who loved her much more. Of course she was free to make assumptions about who this meant. And now that she has again agreed to go through with a match, we worry that something similar will happen and humiliate this poor doctor sahib, and bring further embarrassment on our family.”

The stationer nods his head at this well-told tale.

“It sounds,” he says, “like you need to go to the seller of spare hearts.”

“Has that anything to do with the spare-parts district?” I ask. “That place we do know.” There you’ll surely find spare parts, for every kind of machine and device, but moreover it is an immense thieves’ market, with goods rarer than you could imagine alongside the newest conveniences lifted by the palletful straight from the docks as they come off the ships in Bombay or Calcutta, hundreds of miles away. Once, a little electric motor was stolen from our compound over in the south of the city, near the Yamuna, and our gardener found it all the way up here the very next day, and haggled to buy it back for a fair price.

“I’ve heard of a hearts seller who used to be in Lucknow,” my sister says brightly.

“You know so many things I don’t, Little Pear,” I tease.

“Mahmudabad, actually,” says the stationer. “Although, yes, when Raja Sahib’s lands were seized some years after independence, many of those merchants settled in Hazratganj, in the very heart of Lucknow, but the person you’re thinking of never shifted.”

“Did the Raja’s family get back the old Metropole Hotel in Nainital?” I wonder aloud.

“Yes, exactly,” says the stationer. “And half of Hazratganj, besides. The high court, you’ve surely heard, gave them back most of Mahmudabad.”

“Lucky buggers,” mutters my sister, in English.

“But enough of such feudal gossip,” says the man, though I’d wager it’s himself he’s chastising, as he clearly enjoys it the most among those present. “The hearts seller was nowhere near either of those places—he was in Mahmudabad itself, right in Sundoli.”

“We don’t know the city,” I explain.

“Near the railway station?” he asks.

We shake our heads.

“At any rate, right in the center of the town. But that’s not the point. This one, our Delhi hearts seller, is a nephew of the Mahmudabad one, who must now be dead, or long ago retired back to his village. The family’s reputation is generally one of honesty. Well, as honest as one can be in that trade.”

He wrinkles his nose a little and holds on to his cap as he leans far forward over the counter to spit betel juice into the gutter.

My sister gives me a wide-eyed grimace before he comes back up.

“But for what you’re in need of, I don’t think you can go wrong,” he says.

We take the directions from him, finish relating the particulars of the invitations, and hand him a certain amount for the deposit.

“Be careful though,” he says as we leave. “There are some sweets sellers near where you’re headed who claim to deal in hearts, but whatever they have, what they keep under the counter, is not to be trusted.”

“Oh, look who it is,” I say to my sister. “Isn’t that Rashid?”

We call out and find that it is indeed who we thought: Rashid the tailor.

He greets us with elaborate courtesy. His teeth as always are stained with betel nut. Both men we’ve spoken to today are great lovers of paan.

He asks what brings us to such a cluttered and humble place.

“We’re looking for the seller of hearts,” I say.

“Well, we came here for wedding invitations, but now we’re doing that also,” says my sister.

“The heart seller!” the tailor says. “I’ve just seen him myself.”

He lifts up what he’s carrying in the crook of his arm. It’s a packet bound in cotton shipping cloth, tied with twine, and sealed with wax, the cloth marked in both Roman and nastaliq scripts:

s. ahmed, provisioners

behind green mosque (second

gully, next to abingdon house)

purani dilli

no telephone

“That’s the place we’re looking for,” I say.

“Oh, may I ask why?”

“Our auntie’s quite mad,” says my sister, and leaves it at that. “What about you?”

His pause makes me wish she hadn’t asked, but then he gives a little nod and says, apologetically, in old-fashioned phrasing that conveys modesty and shame, “You see, I am afflicted by a fondness for men.”

I suppose we knew this, but we make vague expressions of commiseration, not reprimanding him for this tendency but also taking care not to congratulate him excessively in his new direction. It is a delicate matter.

“May we see the heart?” asks my sister.

“Of course,” he says, as if he’d been rude not to offer.

“Oh, you don’t have to undo it all on our behalf,” I say, giving my sister a scolding glance.

“It’s no trouble, really,” he says.

My sister offers her hands as a table as he undoes the packaging, breaking the seals (at which I wince for some reason) and unwinding the twine.

Inside several layers of cheap rag padding lies a small bundle of muslin, the heart inside, swaddled tightly like a newborn. He removes the safety pin holding the wrap in place, and then takes me aback by grabbing one end of the muslin and jerking it upward, letting the fabric unspool rapidly and the heart fall into his palm. Perhaps I shouldn’t be surprised, though, as tailors must generally be a sure-handed lot.

He holds his hand out. The heart is small and neat, a handsome little thing.

“Must have cost a packet,” I say.

“It wasn’t cheap,” he says. “But, all thanks to God, I’ve been getting a lot of work from the French who are posted here. They want all the latest fashions copied from Paris. They give me a photograph,” he sweeps his hand in front of himself dramatically, “and I can see the lines true as if they were plumbed.” He thrusts his hand downward and flicks his fingers open with a conclusive gesture.

“Soon we won’t be able to afford you,” I say in jest.

“Your family are as my own to me,” he says, a little offended. “I will not cheat you,” then after a moment, “thanks to God.”

“He’s only joking,” says my sister. “And if you charge ten times as much, we’ll beggar ourselves for shame.”

This is a very poetic sentence, and once more it’s good that my sister, great reader of ghazals and enthusiast of the dastangoi revival, should be the one to deliver it. I would sound like a bureaucrat trying to declaim such a line, my Urdu corrupted and weak as it is from years overseas.

This satisfies the tailor.

“But it won’t ruin me. Look here,” he says, and holds the heart up for closer scrutiny.

“It’s got only one chamber,” says my sister.

“That’s where the price comes down,” says the tailor. “I’m not a rich man, I’ve no need of more than one woman.”

My sister trades small talk with him about when he’ll have her petticoats ready, since three at the least are needed for the wedding. Then we say our khuda haafiz.

Once we’ve taken our leave and walked a little my sister says to me, “For a tailor he dresses very poorly.” It’s not untrue: large clunky sandals that are falling apart, trousers an awkward gray, a shirt of cheap fabric with collar points from a distant past or an unpromising future.

“Oh, be nice,” I say. “That’s not what matters.”

“I suppose not.”

I have a guess why she’s upset. This happens maybe once or twice a year, when she thinks too much about everything that was stolen from our family or lost by foolishness. None of it ever came back. Yet they have always regarded such things with a fatal humor, and made jokes about the circumstances. Like the time our great-grandfather lost half the mango orchards of Kakrauli to the old Nawab’s idiot son in a bet over who could eat the most poached eggs. And who was the idiot then?

All the talk of Mahmudabad has reminded her. I in turn remind her that we are modern people, who live beyond our family. That we move forward in the world by work and by virtue. She nods and casts off her dourness, as she always does. But who doesn’t find loss hurtful in some way, even when it is salutary? Besides, she is younger than I am, and romantic. She feels the loss as spiritual rather than worldly.

She says she would like to get a quick bite to eat, and I make us wait until we see a clean-looking place that seems popular enough that the food won’t have been sitting around all day. It’s not too crowded inside, so rather than go in with her to look after her modesty, I wait and poke around the intersection, where three stone-paved streets come together. There’s a sewing-machine repair shop, a shop selling woven reed baskets, an antiquarian bookseller, and a few of those curious general stores of Old Delhi that seem at once to sell everything and nothing: toothbrushes but no toothpaste, yellowing composition books and dry ballpoint pens, stale peanut brittle wrapped in disintegrating cellophane, warm mineral water, double-edged razor blades, gritty Indian bar soap and expensive imported shampoo. The exterior display counter of the place my sister has gone inside is full of traditional delicacies, and I try to see whether I can recognize them all. Among the laddus there’s the motichoor and besan and boondi kinds, and two I don’t know, but which I don’t think I ever knew. There are old-fashioned single servings of firni in little terra-cotta pots. There’s sing barfi, cham cham barfi, and what must be pista barfi. They even have the kind of barfi topped with real gold foil rather than silver foil.

I realize as if waking from a dream that this is a sweets shop, and there is no queue at the till, and my sister has been inside a long time. I enter and find her talking to a stooped mithaiwala in a lambskin cap who’s showing her a heart resting on a bed of pastry tissue.

“We should go,” I tell her.

“I just wanted to see,” she says. “I’m not going to buy anything.”

“Then let’s not waste this man’s time,” I say, and take her hand.

We get turned around a few times and misdirected by locals who are afraid to disappoint us with an ignorance equal to ours. We curse ourselves for not just asking Rashid to take us there.

“It’s not like he would have minded,” says my sister.

“I know,” I say.

“He would probably be over the moon to spend time with you,” she says.

“Your tongue’s still sour from earlier,” I say sharply. “And besides, he’s gone off men.”

Then we find the heart seller. He’s in an airy little shop with a single empty glass-topped counter and fresh plaster on the walls. The edges of the heavy wooden posts that frame the open shop front are soft from the dozens of layers of paint they have gained over the years. At present they are a bright dusty blue.

The man gives us a shallow nod and a smile.

“I’ve heard tell of your uncle in Lucknow,” says my sister.

“Ah,” he says.

“In Mahmudabad,” I correct her.

“Are you people from that area as well, then?”

“No, not really,” I say. “Our grandfather was chief minister at the court in Rampur.”

“What did you say your family name was?”

We tell him.

“Ah, of course.” He smiles broadly.

I get the curious feeling that maybe he’s dealt with some relative of ours before, but if so he says nothing about it.

“And how may I help such fine folk?” he asks.

My sister tells him our aunt’s story, though with less flourish than she used with the stationer. Perhaps she is trying to give the heart seller something more technical.

He nods throughout, and before she’s wrapped up he waves her off, reaches down into the lower part of the cabinet, and places a heart in the empty glassed-in portion on top.

The heart is fairly plain, though a little less antique and more ornate than the one Rashid showed us.

“Can you tell us about it?” I ask.

“This is one of two that I think would work for your situation,” he says. “It belonged to a simple village woman. She lost her daughter in the field one day, and heard the girl had been taken against her will to Sitapur. This was some time ago. The woman traveled for many miles searching for her daughter.”

“Sitapur in Uttar Pradesh?” asks my sister.

“No, the other one,” says the man.

“Surely not the one in Chhattisgarh?” I say.

“The very same,” he says.

“I would think they’ve nothing to do in Chhattisgarh but steal girls,” my sister says, by which I think she means, Who knows what even goes on in Chhattisgarh. (I hardly do.)

“They are a shiftless lot,” says the heart seller, nodding. “Anyway, the woman reached Sitapur after nightfall, and begged to stay with a little community of farmers on the outskirts, explaining her predicament. They said they would help her look for her daughter the next evening, after finishing work, if she would drive the buffalo for them the next day. There was an illness in Sitapur at the time, and they were short of hands.

“So the next day, the woman tended the buffalo. But rather than shirk her task and pine for her daughter, she was exemplary in her duties. The farmers were charged with righteous feeling at seeing this woman’s honest work, and sought the help of some local higher-ups and generally made a big fuss and a big search until the woman’s daughter was found, in circumstances that are not precisely clear. Maybe she’d been taken as a whore, or to work as a servant, who can say.”

“Sounds like a fine heart,” I say.

“It might work and it might not,” the man says. “I think there’s a good chance, but I don’t want to misrepresent anything.”

“There was another option?” asks my sister.

He removes the heart from the display and returns it to storage. Then he reaches deep inside the cabinet, as if he’s moving several things around and exposing something well packaged. He does not seem a theatrical man, but the amount of time he takes does build our curiosity. When his hand emerges with the heart, we see that the suspense was justified. The heart is extremely fine and clearly very old. Its form is subtle and precise. A masterpiece.

“This,” says the heart seller, “belonged to a prince of the West. One way I heard it told, he was even an emperor. Among the Greeks who lived long ago in Turkey, before the Ottomans took over. He was buried under the walls of the city in which his people lived, a protector even in death. Not one of our Hindustani people, but one of Alexander the Great’s people, who were at one time Hindustanis after a fashion. This prince wasn’t some layabout spoiled rich type, but a soldier, who fought for his people as they faced an unavoidable end. When the walls of his city were taken he looked around and, realizing it would not do to live once his city was fallen, threw himself where the battle raged most fiercely.” He looks heavenward. “Ah, for such days.”

The heart seller perhaps detects a dubious silence from me.

“These things don’t come with the most thorough paperwork,” he says. “But I can tell when things are right.” He taps his head. “When they’re good. This is”—he searches for the word—“an incorruptible heart.”

“It’s beautiful,” says my sister, hardly listening to any of this. “We should take that one.”

Like an idiot, she’s forgotten the first thing about dealing with shopkeepers, and in the Old City at that.

“Even if a tenth of the story’s true,” I say, “I’m quite sure we can’t afford it.”

The man rubs his jaw with a thumb. “Just rent it.”

And then because we are surely surprised, he adds, “I know your family. Your aunt can get married and keep it a while, and you can bring it back when you’re sure it’s worked. It doesn’t sound like she’ll need it indefinitely.”

“She’s far too old for children,” my sister says.

He names a price, with a deposit to be kept as surety. It’s still extraordinary.

“We might have to sell some things to cover this,” I say, and now I am the one who is muttering and thinking about all that we’ve swindled ourselves of.

The day of the nikah, my sister and I are frantic helping to fix everything that has been done wrong by the tradesmen and laborers who have set it all up with the crooked eye and cheerful laziness of the illiterate.

The rows of tables are madly out of line and have to be put straight, which, in fairness to those who have laid out the furniture, proves surprisingly difficult. The props for the tomfooleries are nowhere to be found. The dance floor is sinking into the soft lawn even without people on it. And on and on.

Some of those whose labor went into the preparations are invited for the feast, at which they stand by politely at the edges and eat their fill of the impossibly rich food. The descendants of the old court cooks from Rampur have been dredged up from some village and brought to prepare the dinner in giant cauldrons, using a kilo of ghee for each guest as their rule of thumb, and cooking for twice as many as were invited.

Auntie S— is brought forward by our great-uncle M— and our father, as the closest thing she has to brothers. The doctor looks pleasant enough. They sign the marriage contract. She looks happy.

Rashid the tailor, who is responsible for my sister’s new choli and my new achkan, is among the peripheral invitees. He is engaged to a girl from his village, he tells us. His family found her straightaway. She’s finished six years of school and knows how to speak a bit of English. As soon as he finds a little flat and moves out of his bachelor suite, he’ll send for her.

Later in the evening, my sister asks me whether I think the heart is truly what the heart seller said it was and I say that, as the stationer told us, the man was probably as honest as can be hoped for, and besides that, he’s really the only game in town. But I think I am telling this to myself more than to her.

Three months after the wedding, on a day when the first monsoon rains have cleared the extra dust and people from the streets, my sister and I go back to Old Delhi, and we return the heart. Then, with the deposit money back in hand, we treat ourselves to a big lunch of kebabs, such as we loved when we were children.