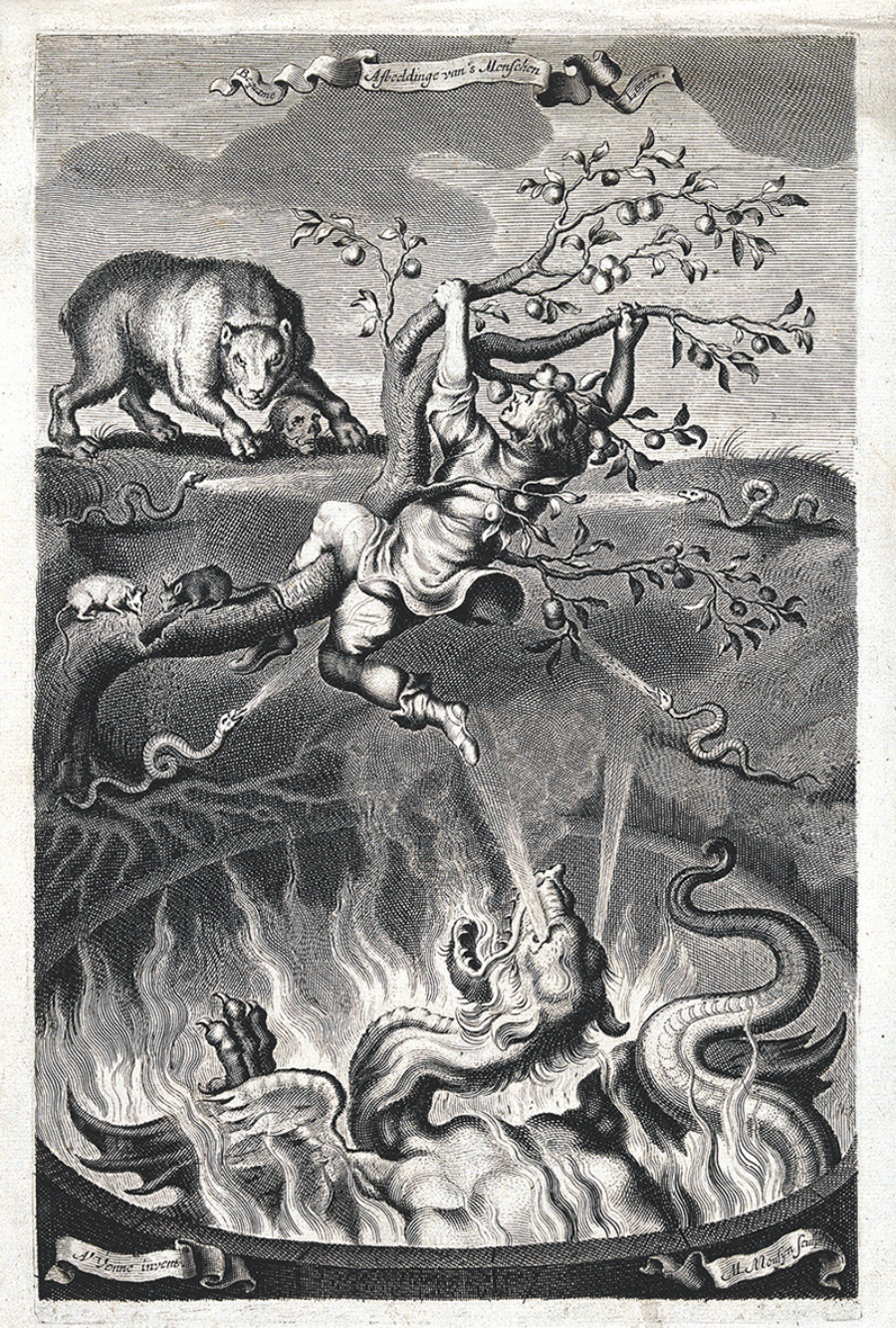

Engraving by M. Mouzyn, after Adriaen van de Venne. Courtesy Wellcome Collection

Dangling Man

It’s a dramatic scene. A man clings to the branches of a fruit tree, a look of terror on his face. He’s certainly in a pickle. The tree is bent over a fiery pit. At the bottom lurks a dragon, beams emanating from its eyes, almost catching the man’s foot. On the rim of the pit are snakes, also emitting some kind of ray—or perhaps poison—from their mouths. In the background stands a ferocious beast with the bulk of a bear but the face of a big cat. Whatever it is, it’s not friendly: between its front paws lies…