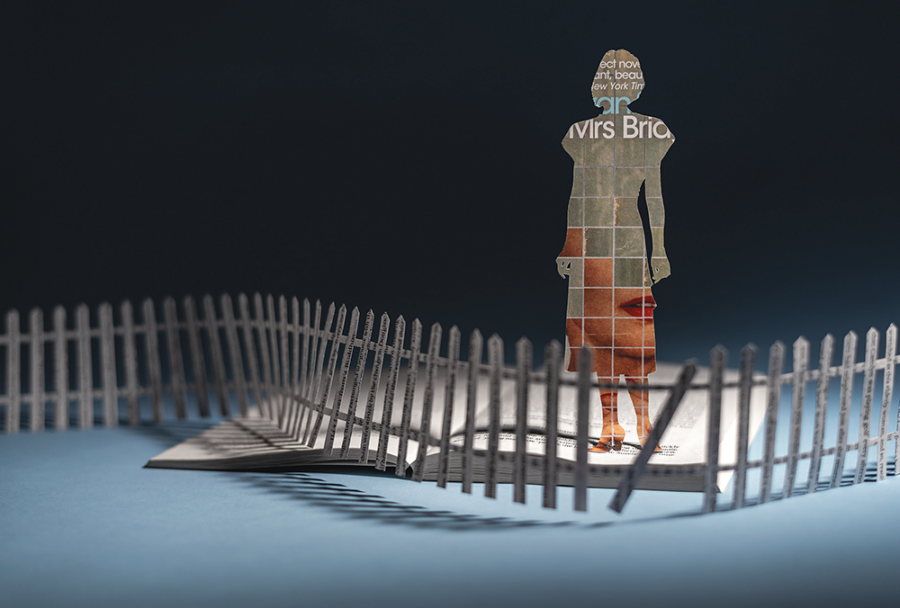

Photograph by Thomas Allen

Discussed in this essay:

Literary Alchemist: The Writing Life of Evan S. Connell, by Steve Paul.

University of Missouri Press. 416 pages. $45.

Typically I’m not much of a rereader; if I really love a book I tend to feel a certain superstition around it, and worry that revisiting it will tarnish the pure, ecstatic lambency of the first encounter. Mrs. Bridge, a 1959 novel by Evan S. Connell, has been the exception. I read it for the first time in my mid-twenties and felt immediately that it was my favorite novel. Since then I have read it…