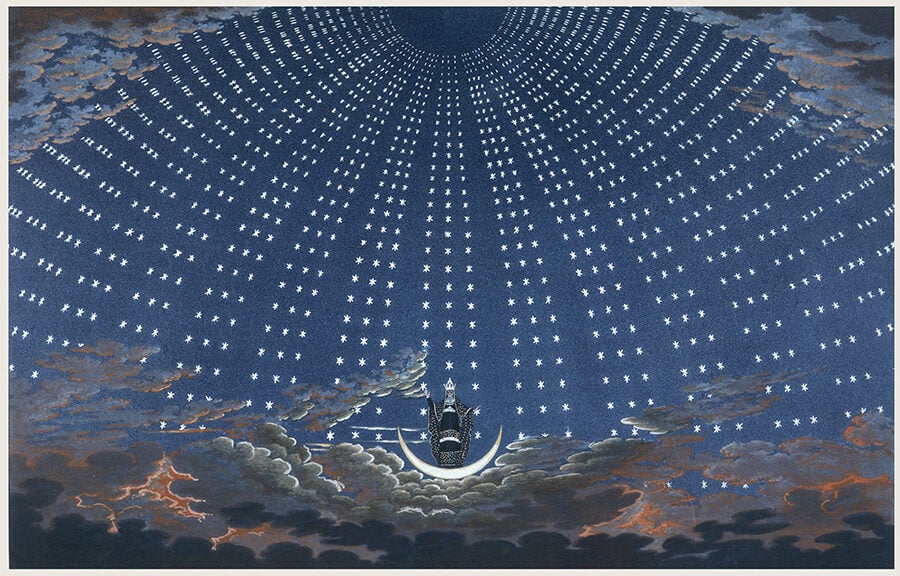

Design for The Magic Flute: The Hall of Stars in the Palace of the Queen of the Night, by Karl Friedrich Thiele after Karl Friedrich Schinkel

A few years ago, my relationship to darkness had turned a bit fanatical. I was living on the Canadian Prairies in Regina, Saskatchewan, and I’d found my way into a regimen of extreme early rising. Waking each day sometime after midnight but well before the suggestion of dawn, I would drape myself in a hooded fleece cape, light a votive as thick as my forearm, and carry it like a torch as I puttered importantly around the kitchen, arriving at my desk to scribble longhand as if engaged in some form of monastic cosplay.

My obsession with the smallest hours of the morning seemed to have something to do with darkness in particular. By rising in the dark and maintaining its integrity, I felt I was evading the tide of linear progression, easing my way into a place of dream-inflected removal where anything was possible but nothing really counted. I’d discovered what Rilke called “the dark hours of my being,” when “the knowing comes,” and I “can open / to another life that’s wide and timeless.”

I’d moved to Regina only a couple of months earlier, after my partner took a temporary job that would keep us there for less than a year. We’d cut a long-term deal on an Airbnb apartment near downtown in a neighborhood that Google Maps insists is named “Transitional.” The area’s blankness felt lived-in: long-suffering construction projects, half-empty parking lots, buildings with boarded-up windows closing their eyes to the street. At the end of our block was a large hospital. From my desk, I would watch the newly discharged patients leave each morning at first light, never dressed for the weather, wandering away from the night like ghosts unglued from their bodies.

Saskatchewan, like its southern neighbor Montana, puts a marketable spin on its flatness. Its provincial motto, “Land of Living Skies,” reminds us that topographic sameness can make room for some big-time empyrean wonder. Regina is a city so bare and crime-ridden and uninhabitably cold that even locals consider it a punch line, but I loved living there. No Reginan ever believed me when I told them so. “You don’t have to say that,” they would respond. Or: “Why?”

The sky was as advertised: monstrous, dazzling, everywhere. I was enraptured by the excess of space. In the midafternoon (which is the end of the day when your day starts in the middle of the night), I often went for long walks, making idle loops around the city. I loved the way each season conjured creative forms of resistance to human life: the dry gasp of winter; spring melt like a fit of largesse; late summer’s bile-yellow moths splattered on windshields and clogging radiator grilles, their bright, dead bodies attracting clouds of wasps.

But for all the hours I spent awake in the dark, and for all the time I spent admiring the breadth of the sky, it never occurred to me to put the two together. I never left the house at night, never drove out of town to observe the stars. My version of the dark was interior and contained. When the spell broke each morning with sunrise, I would blow out my candle, admit the present, and do things like check my email, funnel podcasts into my skull, and scroll through Instagram. That was where I saw a photo of a camping tent dotted with red lights and geolocated with a tag for a “dark-sky preserve” in Ontario. As someone in the business of privately preserving my own corner of the dark, I got curious.

Allegory of Vanity, by Trophime Bigot © Stefano Baldini/Bridgeman Images

The earth is warming, but it’s also brightening: the luminance of the night sky is increasing between 2 and 6 percent each year. It’s not just that there are more of us on the planet: the rate of brightening far outpaces population growth. A recent study estimated that nighttime artificial light increased up to 270 percent globally between 1992 and 2017, and up to 400 percent in parts of Africa and Asia. About 83 percent of humans—more than 99 percent of North Americans and Europeans—live under light-polluted skies. The majority of children born in North America today will never see the Milky Way.

The ecological consequences of eliminating the dark are increasingly well-documented. Under the influence of artificial light, dizzied migratory birds careen off course and can turn in endless circles; insects forget to mate; plant photosynthesis goes haywire; and infant sea turtles crawl up the beach onto lit-up roadways to be squelched by cars. Scientists have documented a 76 percent decline in flying insects from 1989 to 2016; light pollution has been identified as a crucial factor. And the human animal is hardly immune: we are blinkered and sleepless, saturated with artificial rays that jolt our metabolic systems like a drug. Overdosing on artificial light—or, to put it differently, denying ourselves darkness—is linked to cardiovascular disease and obesity, depression and diabetes. Some researchers are ready to classify our light-disrupted circadian rhythms as carcinogenic.

Darkness has become endangered, and beyond the ecological or biological effects, there are other, arguably greater losses at stake. For as long as we’ve been human—and possibly longer—we have looked to the heavens to find ourselves. Our view of the stars and planets has been crucial to the physical sciences, to navigation, to religion, to myth. Every culture makes meaning from our vantage on the stars, etching patterns, projecting stories and beliefs overhead. In that sense, artificial light is blotting out access to the primary source text of our cultural heritage.

For all the threats that the bright skies pose, the darkness conservation movement is relatively young. Founded in 1988, the Tucson-based International Dark-Sky Association is the principal global accreditor of darkness, awarding five different classifications to “dark-sky places.” Canada, however, has its own set of dark-sky designations. In fact, it holds its darkness to slightly higher standards than the IDA, applying more stringent criteria to the color and directional cast of the limited night lighting permitted in its dark-sky preserves. While the IDA is a staffed nonprofit focused exclusively on light pollution, the Royal Astronomical Society of Canada is an older association overseen by volunteer stargazers, some of whom call themselves “RASCals.”

Of Canada’s twenty-six certified dark-sky sites, the darkest is Grasslands National Park—180,000 acres of protected badlands and prairie only 210 miles southwest of Regina. To measure darkness, RASCals use the nine-point Bortle Dark-Sky Scale. Unprotected rural areas typically hover around three, while the most saturated urban cores are an eight or nine: that faded, purplish wash that passes for night in a city, where light scattering in the atmosphere can make the sky bright enough to read by. Grasslands is a scant class one: the darkest the sky gets on earth. “We’re talking about world-class darkness,” one RASCal said, boasting that the Grasslands sky is practically a Bortle zero (the scale doesn’t go this low, but I took his point: it’s really dark).

After several years cultivating my early-morning communion with the dark, I decided to go to Grasslands and immerse myself in the real deal—the raw, exposed, outdoor kind. With neither the equipment nor the wilderness skills for a backcountry expedition, I planned to stay at a roadside motel and venture out for two nights of solo hiking and dark-sky gazing. I cross-referenced potential dates with a lunar calendar, looking for nights when the intrusion of the moon—what Shelley once compared to “a joyless eye”—would be minimal.

My rationale was not that complicated: in a moment of apocalyptic overtures, I was craving something elemental. I was looking for something pure, something timeless—the darkest dark sky in all the land. In the dark-sky movement’s effort to preserve the night from the encroaches of artificial light, I recognized something of my own formless longing. What was the dark, I wanted to know. If we could have it back, what might it show us?

“If we keep the eyes open in a totally dark place,” Goethe wrote, “a certain sense of privation is experienced. The organ is abandoned to itself; it retires into itself.” This, I think, is more or less what I was looking for—a return. I hoped to abandon myself to something I already possessed. I wanted obscurity so totalizing it might convert into clarity.

Our attachment to light is old and tenacious. Light is knowledge, vision, truth. A clever person is brilliant; someone lovely lights up the room. We shed light on an issue to provide insight, and when we are struck with epiphanic understanding, we have seen it: the light.

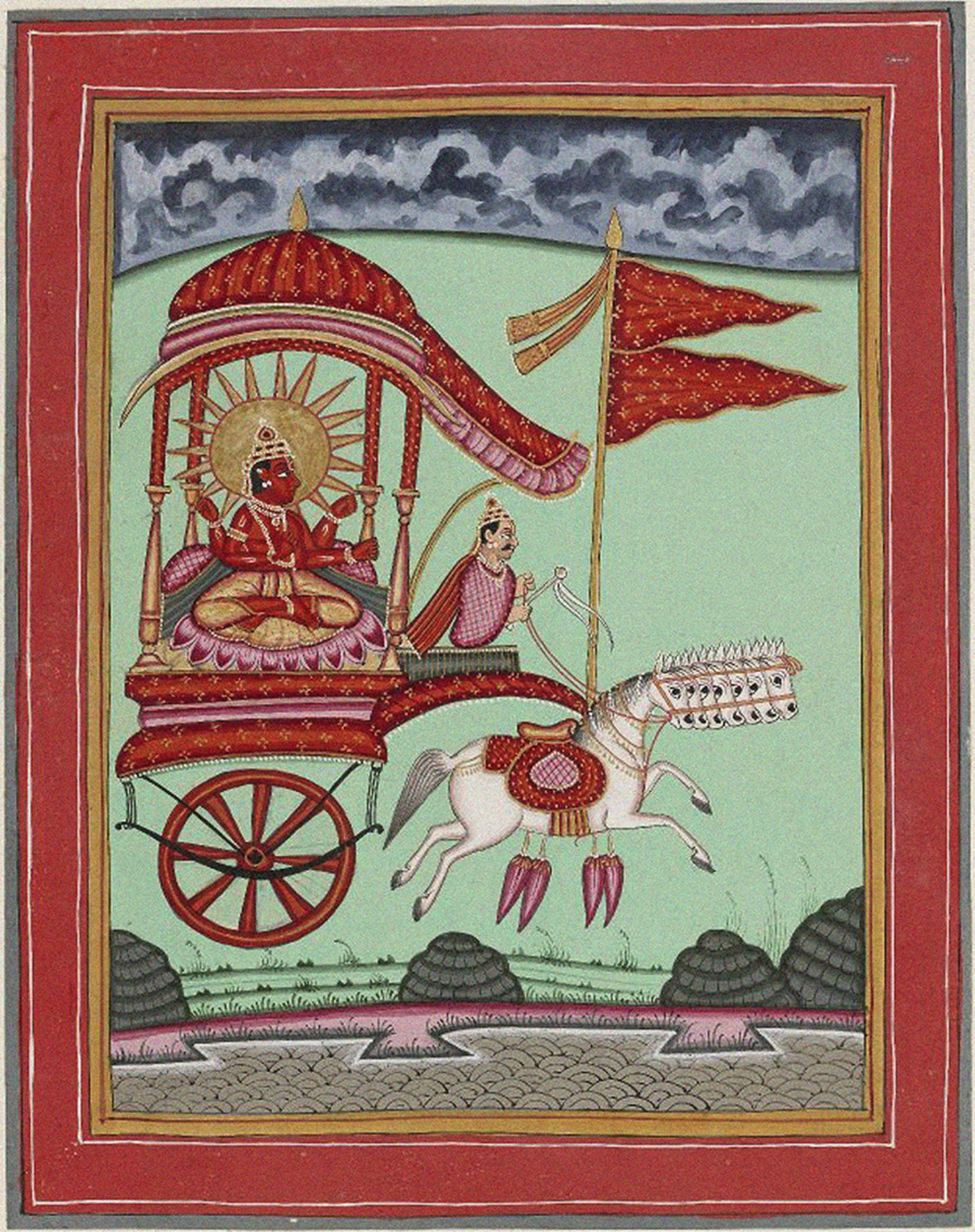

According to the Rigveda, the sun god Surya drives a horse-drawn chariot across the sky, expelling the dark and its evils, while in ancient Egypt, the solar deity Ra was thought to battle a serpent of darkness in the underworld each night, returning in the morning to bring light and life back to earth. Many indigenous peoples of the North American Plains gather annually for a sun dance to celebrate seasonal renewal and the coming of the light. In the Old Testament, light is the first thing God orders into the universe: fiat lux, let there be light.

In Plato’s Republic, Socrates describes the sun as “the offspring of the Good.” Its light is to the visible world what goodness is to the world of pure knowledge: an illuminating presence, a necessary condition for truth. The sun offers a material analogy for the very form of the Good—a goodness beyond the realm of sense, time, or space. Manichaeism—a Gnostic religion that thrived in the third century—frames all of existence as a struggle between light and dark; its founder, Mani, was called the “Apostle of Light,” the supreme “Illuminator.” In twelfth-century Persia, Illuminationist philosopher-mystics pictured the corporeal and the immaterial along a spectrum of light and dark, with pure light as the highest form of presence.

And yet, even in the persistent dualistic understanding of light as good and dark as bad, there are gradients and complications. Light and dark appear on the Pythagorean table of opposites, for instance, but the associations are not entirely intuitive. Light is aligned with “the one,” and “good,” but also “odd,” “motionless,” and “limited.” Darkness, meanwhile, is “unlimited,” “motion,” “even,” “bad,” and “the many.” Light, for all its virtues, does not give us everything—it is square and finite, still and inconsistent.

In the Greek pantheon, light derives from darkness: Nyx, the night, couples with Erebus, the dark, to birth Hemera, the day, and Aether, the bright sky. Day is hitched to night, the hours to the sun and the moon. In The Iliad, Nyx’s “hateful darkness” is one of the forces to which even Zeus is subject.

This is a common thread in many creation myths: dark first, light second. Sometimes, this darkness takes the form of a watery void into which the world is birthed; at other times, we begin inside the dark of a cosmic egg, a seed, or the body of a god. For the Zuni people of the Southwest, the first humans on earth are crowded in four dark, subterranean worlds until they are led into the light by the children of the sun. According to the Kuba and Boshongo of Central Africa, the god Mbombo, or Bumba, is alone in the dark until he vomits up the sun and heavens. In the Haudenosaunee creation story, the first woman falls to daylit earth from a dark hole in the sky. Light is an intervention; darkness is original, primordial, the backdrop against which conception is forged. Life is only appreciable by way of the absence that precedes it.

Taoism takes this further. Rather than position light and dark as locked in a hierarchical binary, it suggests that darkness has its own relationship to truth. Obscurity is part and parcel of revelation. In the Tao Te Ching, the named and unnamed parts of reality “spring from the same source but differ in name; this appears as darkness. / Darkness within darkness. / The gate to all mystery.”

Light is facile; it does all the work for us. In the modern, well-lit world, our powers of observation are spread out, vitiated, diluted. Too much light makes it impossible for us to see: the human eye adjusts its baseline to the brightest thing it can find, so one point of excess changes the whole, makes everything around it obscure. Picture a sports field at night, how everything beyond the purview of the floodlights transforms into an unreachable void. Turn off the lights, and the undifferentiated shadows might reassert themselves as recognizable shapes and objects.

Light is attractive, yet distorting. The dark, on the other hand, doesn’t distract or astonish—it waits, calls us back. We have to work harder to attend to darkness, but you may be more richly rewarded for it. The lit world may be the one we crave, but there are things we need from the dark.

It started to rain as I drove into Val Marie, a tiny village of about a hundred people on the edge of Grasslands National Park. For long stretches of the summer, the sky had been withheld by smoke from wildfires burning across the north of the province, and it hadn’t rained in weeks. Now a succession of fat drops was accumulating into what would, by evening, become a steady drubbing. “Sorry for you, but not sorry for the land,” a ranger at the visitors’ center told me.

I only had two days to deliver myself to the darkest dark sky, and the first night was a wash. I stayed in my room at the motel—which seemed to double as a junkyard, with a bank of trailer suites plunked in a field alongside a sunken jalopy, rust-cankered farm equipment, and a small amphitheater of nonfunctional toilets—and considered watching a movie from the VHS selection. The best choice was Field of Dreams, but all I could think of was how Ray Kinsella was a criminal-level light polluter.

The next day, the rain had stopped but the cloud cover remained, leaving the diurnal hours loose and formless—the sky gray-bright and hard, the wind so strong it felt personal. The landscape was enormous, but not entirely flat; the park’s main scenic drive ran along the rim of the Frenchman River Valley before descending into the wetlands below. I spent the day wandering around, watching bison hulk across the expanse like roving geologic features. Closer, hundreds of prairie dogs chirped and scattered, popping out of underground tunnels and scratching at the earth with furious, devotional intensity.

The sky was still gauzy as I stationed myself by one of the lookouts above the valley, where I planned to catch the first stage of nightfall. As the dark descended, I could sense more than see the drop-off on one side of me. In every other direction, the emptiness seemed to elongate, growing bluer and more chilled. It stayed cloudy for a while. I started to wonder whether I would get what I came for. But then it happened: crossing into astronomical twilight, layers of cloud and light peeling off the sky like fine plies of tissue, more and more stars exposing themselves by the minute. I kept thinking I’d arrived, hit the limit of the dark, and then the sky would dig a little deeper, find another reserve. Somewhere toward the horizon, coyotes yipped and howled like spooky, discordant yodelers.

The eradication of darkness may seem like a fringe, superficial issue to get worked up about—more of an aesthetic problem than a load-bearing one. Pontificating about spectrum and glare and sky glow at this late hour might sound like fussing over design details when the house is on fire. But rather than a straggler on a lengthy environmental fix-it list, we might instead think of darkness as a synecdoche for the basic problem of human imposition on the natural world, the fundamental assumption that it’s ours to conquer.

Many other human-generated problems are hard to picture, hard to measure, hard to hold in focus. The dark night, by contrast, is retrievable: beyond the insomniac scrim cast up by human activity, the sky is still there, in its pristine, original condition, just waiting to be witnessed. If we made concerted changes—formally declaring artificial light a pollutant, implementing ordinances, swapping in more responsive technology, funding dark-sky preserves—we wouldn’t have to wait decades or generations to see the dividends. The magnificent starscape could be delivered to us right away, with the flick of a switch, at the speed of light.

Part of me, then, was hoping to glimpse the resolution of a solvable problem—to preview some achievable goal, a place we could return to if we really tried. In my mid-thirties and mind-warpingly ambivalent about procreation, I wanted to stand in a field of grass and believe that the future could be a place worth existing in, that there might be some value in human continuation, that we could reform our relationship with the planet and make good. I wanted the dark sky to tell me that it was possible, that it was worth it.

Constellations rising above Eagle Butte at Grasslands National Park, Saskatchewan. August 26, 2019 © Alan Dyer

The biggest obstacle to reclaiming the night sky, conservationists say, is fear of the dark. This is a big theme in the dark-sky movement: that it is fear, not reason or progress, that motivates us to build our lives around light. What are we so afraid of? How have we devolved into a bunch of scaredy-cats?

From the Middle Ages to the early modern era, darkness dominated the night. In medieval Western Europe, cities kept curfews, chaining the gates shut at night and tolling a bell when it was time for residents to retreat to the safety of their homes, snuff out their candles, and stay put until morning. Watchmen patrolled the streets, and in larger cities such as Paris, Vienna, and Berlin, citizens were required to lock themselves in their homes and hand their keys over to local authorities. Residents took cover from the dark as if from a natural disaster.

At night, nature asserted itself over human industry; fragile systems of social, religious, and political order lost their authority. In At Day’s Close, an account of night in preindustrial Europe, the historian A. Roger Ekirch describes the onset of darkness as both freeing and frightening. Many found respite and refuge in the dark for its anonymity, privacy, and release from the demands of labor. And yet there was also much to be wary of: at night, the undeveloped landscape transformed into a series of pitfalls; spirits, ghouls, and demons were believed to lurk around every corner; the sky lit up with inscrutable celestial omens. The dark was thought to have physical substance, containing deleterious vapors that descended from the sky and threatened the lungs.

The Enlightenment was literal: throughout the long eighteenth century, thousands of lanterns were strung overhead and streetlights were erected in cities across Europe. Little by little, darkness was chased out of shared space. Light became public—a symbol of order and control. (The transformation of Paris into the city of light was, in fact, the brainchild of the chief of police, who sold Louis XIV on the idea.) The geocentric universe was decisively unseated, and reason and empiricism triumphed—theoretically—over superstition. For the leisure classes, at least, dark nights went from a metaphysical terror to a practical inconvenience. The transition from dark to light became less about a distinction between night and day than between rural and urban, poor and wealthy.

With the widespread introduction of gas lamps by the middle of the nineteenth century, light proliferated even farther. Over a few short decades, cities across Europe and North America tore up their streets to install gas lines and factories—usually at the expense of the poorest neighborhoods, which were also the least likely to enjoy the benefits of being lit. “The work of Prometheus had advanced by another stride,” wrote Robert Louis Stevenson, waxing nostalgic about the pleasures of gaslight in 1878. “The day was lengthened out to every man’s fancy. The city-folk had stars of their own; biddable, domesticated stars.”

As Jane Brox points out in Brilliant: The Evolution of Artificial Light, gaslights represented an abstraction that would eventually find its final form in the modern electric grid. Private homes were integrated into a public network, which delivered a commodity that had quickly become a necessity. An even-tempered flame appeared straightaway, with nothing visibly consumed or in need of tending. The provision of light took on a semblance of ease and convenience.

In the 1870s, the first electric lights arrived on city streets. These were arc lamps—a pre-Edison technology that generated a bright vault of illumination across the gap between two carbon rods. Too bright for indoor use, arc lamps lit public squares and plazas, railway depots and circus tents, avenues and parks. Their light was a little much: synthetic, desaturating, capable of almost solar levels of retinal abuse. Obviously, such a thing would be popular in America. In the late nineteenth century, thousands of arc lights were installed in cities such as Detroit, Chicago, and New York, but also Aurora, Wabash, and Laramie. Some American cities built “moonlight towers” that reached 450 feet tall, harnessing clusters of lights in hopes of illuminating entire cities under a simulated lunar cast.

To some, the advent of electric outdoor lighting was a marvel, but many found the arc lamp’s gaze disconcerting: blue-tinged, unflattering, and given to odd strobing. The light beat down at unexpected angles from the moonlight towers, leaving startling snares of shadow on the ground. Stevenson called the electric lights “a new sort of urban star . . . horrible, unearthly, obnoxious to the human eye; a lamp for a nightmare!” adding that they were suitable only for “murders and public crime, or along the corridors of lunatic asylums.”

Picture what comes next in a series of brief, flash-lit illuminations: Thomas Edison, in Menlo Park, New Jersey, perfects the incandescent bulb. “Put an undeveloped human being into an environment where there is artificial light, and he will improve,” he speculates. By 1930, 70 percent of American homes are wired for electricity. The light bulb becomes a symbol of realization—the sudden achievement of clarity, the arrival of an idea. The grid becomes a metaphor for human civilization. A time-lapse video of the twentieth century, the earth from space at night: detached globules of light edging toward one another like something organic taking root, pulsing as it grows, brighter and brighter, the edges blurring together.

After about an hour of stargazing over the valley, I nosed my way out of the lookout with my headlights on low. Hunched forward and squinting, I drove the slowest I’ve ever driven along dry, empty roads, to another area of the park. There, I planned to hike up a section of the 70-Mile Butte trail to the highest point in Grasslands for one final, unimpeded view.

I arrived at the trailhead just past one in the morning and started up the path, guided by a tight circle of dim red light from a dark-conserving headlamp. A little way into the three-mile loop, I turned the lamp off. After letting my eyes settle, I found I could do without it, feeling my way by the haptic crunch of gravel under my boots and the delicate cast of the Milky Way overhead.

Dark that dark changes your sense of space, which changes your sense of speed, which changes your sense of time. As I continued along the trail, it seemed as if the intervals between things had come unhooked. Objects in the far and middle distance didn’t disappear but instead began to flatten, becoming a tableau of broad suggestions—an array of possible outcomes, all equally plausible on their face. In the immediate vicinity, new facts pressed discomfitingly close. Strange details seemed to be pulled up and coaxed into focus, the edges of grass and rocks like shards of silver prickling in the worn-out gray. Under the surprisingly sure wash of starlight, I held my hand out and could see, with almost hallucinatory clarity, a tiny heartbeat fluttering under a vein.

As I hiked, the corners of experience dragged out into a duration my body could no longer estimate, and I soon had no idea how far I had traveled. The trail snuggled down to a low point as hills rose around me, denying all attachment to the road, or farmland, or the village of Val Marie, and then I was climbing. Minutes passed. I’d soon made my way through the switchbacks on the sharp side of the butte and was summitting, breathless, arriving at the terminal station, stepping up to a flat promontory that reached toward the heavens like an open hand. A lone coyote whooped in the nest of shadows far below me. I lay down on the ground.

The dark sky is where clarity and obscurity meet. It is devilish and ghostly, witchy and weird—yet also touched by some potential for holiness. This comes from both the dark itself—the rich implications of its mystery and concealment—and from what preserved dark skies reveal: an unmitigated view of the cosmos that is and has always been out there, quietly lording over us all.

A different way of putting this is that there are two kinds of darkness in dark skies. The first is private and enigmatic, strange and contained—a point of access to a denuded experience of interiority that we’ve largely expunged from contemporary life. The second is the darkness of the commons, an enormity that disintegrates a person’s particular experience, reducing it to a series of temporary sensations. One part of the dark sends a person deeper into themselves; the other forces them to surrender to the world’s totality.

A world of unceasing light is a world of disenchantment, in which everything is knowable and nothing is beyond us. In practical terms, overuse of lighting is linked to unchecked growth and consumption. In spiritual terms, it’s about dominion and power: over the natural world, over time, over death. You might even say that fear of the dark and anxiety about mortality are two manifestations of the same terror—of disappearance, uncertainty, ignorance.

But despite my sympathy for those dark-sky preservers who lament a culture so seized by fear that it would annihilate all mystery, the truth is that I’m totally scared of the dark. Lying there on the butte, I found myself remembering when I was little, maybe four or five, and going through a phase of real terror, when even the rough, marigold glow of my moon-rock night-light was insufficient protection. One night, my dad woke me up and gently led me down into the unfinished basement, with its cold concrete floor, its monstrous shapes and shadows. We sat quietly together, surrounded by everything I was so scared of. Soon, he told me, if we just waited, and if we kept our eyes open, our vision would start to change, and the frightening would transform into the familiar. The world wouldn’t be different—but we’d be able to see it differently. You just have to be patient, he told me. Your body will adapt, then something will shift, and your mind will follow.

Now, with the coyote still howling somewhere down below, the sky above me was exactly as promised: physics-defying, ancient, reorienting. The thing about the dark sky is that it’s really incredibly bright, the Milky Way an impossible, multidimensional reef in the night’s ocean, a star-washed breeding ground for brighter and more pressing stars. Somewhere, a neonatal, two-day-old moon was making its contribution, but I couldn’t find it in a sky so rewilded with light—a chaos without order or sense.

Dark-sky talk is often steeped in antediluvian nostalgia for a world where our lives were more attuned to nature, harmonized with earthly cycles of day and night. But it’s a Janus-faced thing—dark skies allow us to see what our ancestors saw when they turned to the heavens, but they may also offer an apocalyptic preview of what the world will look like after we are gone.

I lay still and breathed as tensile, pointless waves of fear passed through me, dissipated, and re-formed. I thought about how I had lived a life so gentle that this is what passed for bravery: the chance to be alone with wonder. To be struck by awe that seemed to reach through to my skeleton and shake loose from my cells the stunning certainty that every one of them would eventually cease to replicate, and die. The time that passes will not repeat. There is only one direction. And if time seems moldable, or altered, or unhinged, that is only ever a way that it is seeming, a distortion invented to make it all more particular and personal, a little easier to bear.

Though it’s a myth that most of the stars in the sky are already dead and gone, it’s true that all the light we see is old. The sky is an asynchronous historical record: a sampling of long-past moments across millennia, all of it moving away from us, faster and faster the farther out it gets. The stars were growing distant, receding, leaving more darkness in their wake. But to my eyes, they seemed to be closing in like a fleet of messengers, a great wing of consequences arriving to fix me in the present. I kept my eyes open, waiting for it all to shift.