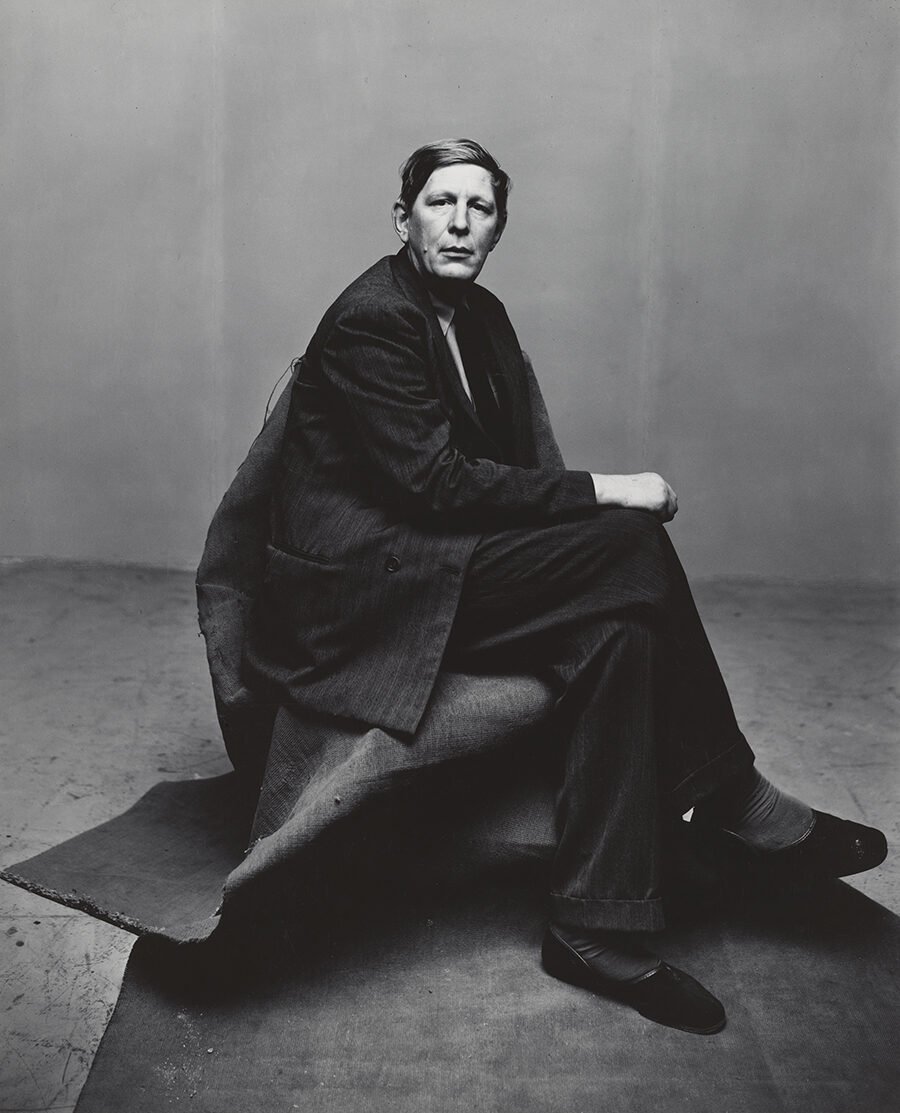

Photograph of W. H. Auden by Irving Penn, 1947 © The Irving Penn Foundation

Discussed in this essay:

The Complete Works of W. H. Auden: Poems, Volume I: 1927–1939, edited by Edward Mendelson. Princeton University Press. 848 pages. $58.70.

The Complete Works of W. H. Auden: Poems, Volume II: 1940–1973, edited by Edward Mendelson. Princeton University Press. 1,120 pages. $60.

One evening in August 1933, after hearing some new poetry read aloud, the British diplomat and politician Harold Nicolson opened his diary and made a confession:

A man like Auden with his fierce repudiation of half-way houses and his gentle integrity makes one feel terribly discontented with one’s own…