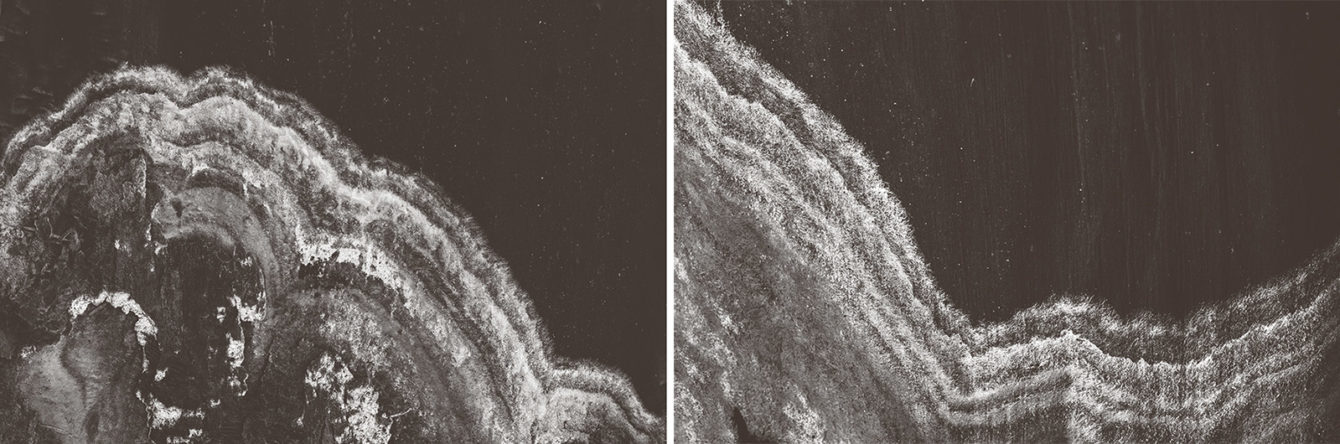

“Big-leaf Maples, Hoh Rain Forest,” by Lee Backer © The artist

With the right equipment and a little luck, stealing a tree from a swath of land as remote and vast as the Olympic National Forest should have been easy enough. In the summer of 2018, Justin Wilke, a Washington man in his late-thirties, found what seemed like the perfect candidate for poaching: a big-leaf maple located about a quarter mile from the Elk Lake trailhead on the forest’s eastern edge. A small number of big-leaf maples, which grow from British Columbia to southern California, have a distinctive grain that makes them particularly valuable. When these trees are milled and finished, they reveal a watery psychedelic pattern that resembles something between a hologram and a Magic Eye image. Specimens can earn a few thousand dollars each at a lumberyard, from which the wood will eventually find its way to specialty furniture makers and luthiers. Wilke needed the cash, and judging by what he saw when he peeled back the bark, this tree promised spectacular markings.

That summer, prosecutors would later allege, Wilke had already poached three big-leaf maples in the Elk Lake area, bringing blocks of the felled trees to his home some nine miles from the trailhead, where he cut them into smaller blocks to sell nearby. Altogether, the value of the wood totaled $4,860. For Wilke, who lived in a run-down trailer, that was a lot of money.

Now he was going after a fourth maple. On August 1, Wilke, his girlfriend Cassie Bebereia, and two associates he’d hired for the job, Lucas Chapman and Shawn Williams, set up camp near the trailhead. A few hours later, the three men hiked into the forest and began to clear the trees around their target. In the process, they found a wasp’s nest in the base of the maple. Their wasp spray wasn’t effective, so they decided to set the nest on fire. After failing to extinguish the blaze, Wilke and his team fled the scene.

Several hours later, a hiker reported a wildfire. By the time firefighters arrived, the flames had spread to the canopy, making quick work of the old-growth forest. Choking plumes of smoke were visible for miles. Over the next three months, the Maple Fire burned more than three thousand acres of pristine forest.

Wilke was a leading suspect from the start. It was clear to firefighters that whoever had tried to cut down the tree had likely started the fire, and Wilke had been spotted at the scene. In late August 2019, he was charged with eight crimes, including conspiracy, theft of public property, trafficking in unlawfully harvested timber, and using fire in furtherance of a felony. Prosecutors felt reasonably confident, but to bolster their case, they decided to turn to an unlikely source of evidence: tree DNA.

For over a decade, law enforcement officers in Washington had been speaking to a U.S. Forest Service tree geneticist named Richard Cronn about the prospect of using DNA to aid in the fight against poaching. Through genetic analysis, Cronn claimed, he could theoretically match any given tree stump to an individual piece of wood in a lumberyard. As the Maple Fire spread, one of the investigating officers, Phil Huff, gave Cronn a call. Could he help Huff’s team determine whether there was a genetic link between the felled trees in the Olympic National Forest and the wood that Wilke sold to the lumberyard?

Cronn told him it was possible, so long as he had money and time. In order to determine a match, he first needed to collect enough big-leaf maple samples to create a genomic database, but he thought he could complete the work ahead of the trial. Huff was thrilled. These cases could be difficult to prosecute, and Cronn’s research promised to determine whether Wilke was responsible for tree theft, if not for the fire itself. If Cronn could pull it off, it would be the first time that the federal government used tree DNA in the prosecution of a poaching crime—a legal tactic that could dramatically curb timber theft both domestically and abroad.

Illegal logging destroys habitats, contributes to erosion and the propagation of invasive species, hurts indigenous communities, and interferes with carbon sequestration and the production of fresh air. It’s also extremely lucrative. Timber trafficking generates $50 to $150 billion each year. Around 10 to 30 percent of the international trade in timber is estimated to be illegal; in the tropics, the figure is closer to 90 percent. The business is violent, often tied up with drug smuggling, game poaching, money laundering, and the persecution of indigenous leaders and environmentalists. As U.S. Customs and Border Protection puts it, “The illegal timber trade is soaked with blood.”

Much of this wood comes from South America, Southeast Asia, sub-Saharan Africa, and Russia—business driven in large part by the demand for alluring, durable wood in the West. But the United States has its own logging problem. Roughly $100 million in tree theft occurs each year on Forest Service land alone. To combat the illegal timber trade, the United States relies on several federal laws, chief among them the Lacey Act, the first federal law enacted to protect wildlife. Originally passed in 1900, it penalizes the trafficking of any “fish, wildlife, or plant” protected by domestic or foreign law. Violations can result in fines of up to $250,000 and sentences of five years in prison.

Such laws, however, can be hard to enforce. Part of the trouble is that it’s difficult to determine the origin of a given piece of wood. For domestically harvested wood, a logger must secure a permit from the relevant government agency, and a lumberyard must check that permit before purchase. But some lumberyards are less scrupulous than others, and a logger can easily furnish a permit from one location when the wood has been sourced from another. The international trade is similarly easy to game: documents required by U.S. customs officials can be falsified, and illegally logged wood is often concealed in legal shipments.

Every advocate and researcher I spoke with had long understood the potential for tree genetics to help combat the illicit timber trade. Trees, like humans, each have “some degree of local history” encoded in their DNA, Cronn told me—offering clues as to where that tree grew before being harvested. But parsing a tree’s origins requires a huge amount of data. Only with a sufficiently large number of samples would Cronn be able to acquire a full picture of big-leaf maple’s genetic diversity, which he could then use to definitively match a stump in the woods to a board at the lumberyard.

Meaghan Parker-Forney, who then helped run the Forest Legality Initiative at the World Resources Institute (WRI), a nonprofit focusing on environmental research and advocacy, told me that for years she attended conferences where scientists like Cronn argued that tree science could be leveraged to prevent theft. “But every time the scientists stood up to give their presentation,” she said, “they would be like: ‘These tools are totally usable. We just don’t have the reference databases.’ ”

The Maple Fire finally gave Cronn the opportunity he needed. With roughly $30,000 granted by the Forest Service, Cronn and his research team (which he fondly referred to as TSI: Tree Scene Investigation) quickly mobilized, collecting twigs, core samples, and leaves from 235 big-leaf maples growing between Hoodsport and Quilcene—an area of about 230 square miles, by his estimate. Once the collections were complete, his team ran the samples through a mass spectrometer, enabling them to determine genetic links between a specific stump and a specific piece of lumber. They then analyzed the DNA taken from the stumps in the Olympic National Forest, as well as one of the boards that Wilke had sold to the mill. They found a match.

Wilke opted to fight his case in court. In June 2021, it went to trial. One of the prosecution’s chief witnesses was David Jacus, the Forest Service officer who responded to the Maple Fire theft. At the time of the fire, he told me, he was the only officer responsible for all 600,000 acres of the Olympic National Forest. His job had him attending to everything from stalled cars to lost hikers to forest fires to the occasional murder to, of course, tree theft.

Jacus told the jury that around 2 pm the day after the Maple Fire broke out, he got a call from the Puget Sound dispatcher informing him that a fire crew was requesting assistance near Elk Lake. He drove his truck up Forest Service Road 2401 just in time to see a Chevy Trailblazer heading away from the scene. Jacus continued along the spur road toward the smoldering tree, where the fire crew had recovered a Mossy Oak–branded camo backpack stuffed with a bright orange sweatshirt and logging gear, as well as a gas canister.

Wilke had been working in the logging industry off and on for years (his Facebook profile listed “a wood cutter at logging” as his occupation). But while he was a skilled tree feller, neither Wilke nor his co-conspirators were great criminals. When Jacus caught up with him at the Elk Lake campsite and asked what he’d been doing at the trailhead, Wilke said he’d gone there to use the bathroom. Jacus asked whether he’d been involved in any illegal logging in the area, and Wilke said he didn’t even have a chain saw. Later, Wilke’s girlfriend told Jacus the same thing. But when Jacus stopped by Wilke’s trailer—which was surrounded by sawdust and wood shavings—his neighbor later identified the backpack as belonging to Wilke. Among the many tools it contained were chain saw chains.

On the witness stand, Jacus identified Wilke as the person he’d seen fleeing the scene. He had also visited a nearby lumber mill, where he learned that Wilke had sold more than two hundred blocks of big-leaf maple that summer using permits for land in nearby Lilliwaup and Hoodsport. The former property contained no maple stumps, the latter contained two. The owner of the lumberyard testified that Wilke told him he was going to fell another tree just days before the fire.

Wilke was emblematic of a basic fact about the illegal timber trade: although it is big business, tree poaching is deeply tied to poverty. The forest offers a last-ditch haven for those whom society has failed. Wilke had struggled to find steady employment over the years; his trailer, at the time of the Maple Fire, lacked running water. One of his conspirators had recently been released from prison, and the other had been living off of Social Security.

All the same, timber theft is a crime, and the preponderance of evidence was damning. The prosecution, however, wanted to further strengthen its case. In the final days of the trial, they called Cronn to the stand. He explained the creation of the database, how it could confirm a particular board’s provenance. His team had studied the genomic sequences of the stumps from the trees Wilke was accused of cutting down, he told the jury, as well as the wood he had sold. Their analysis determined that Wilke sold eighty-three blocks of poached wood to the lumberyard. When the prosecution asked about the odds of a random match, he answered, “One in one undecillion”—a one followed by thirty-six zeros. The defense declined to cross-examine him.

Human DNA can be a flawed tool in criminal cases because it isn’t always possible to prove how a sample ended up at a crime scene. Not so with tree DNA. The evidence was so thorough, in fact, that one of the public defenders cited Cronn’s research as exemplary of proof “beyond a reasonable doubt” in her closing statement. The prosecution had not, however, offered the same standard of proof when it came to the fire, she contended—it had been dark, and neither Chapman nor Williams could testify that they had seen Wilke light the fire, or that he had asked them to do it on his behalf.

The jury agreed. After a seven-day trial, they declined to convict Wilke of starting the fire. He was, however, found guilty of conspiracy, theft of public property, depredation of public property, trafficking in unlawfully harvested timber, and attempting to traffic in unlawfully harvested timber. Wilke was going to prison for twenty months for cutting down some trees—a sentence that the prosecution hoped would serve as an example. Cut down a big-leaf maple, and suddenly the poacher finds himself in the position of a high-end art thief: in possession of a valuable product with no way to sell it.

Photographs of a big-leaf maple after a fire, by David Paul Bayles © The artist

Cronn’s database was the key to securing a conviction in Wilke’s case. But it wouldn’t be much help outside the Elk Lake area. To fight big-leaf maple theft more broadly, law enforcement would need samples from the species’s entire range. The creation of such a database would require hundreds of samplers fanning out across thousands of miles, and the Forest Service still lacked the resources for such an undertaking.

Then Cronn caught a lucky break. Shortly after he testified in the Wilke trial, he got a call from Parker-Forney of the WRI. Her organization was assembling its own big-leaf maple database. She had secured the partnership of a nonprofit called Adventure Scientists, which trains and equips outdoors enthusiasts to collect data from U.S. wildlands for scientific use. Since 2011, Adventure Scientist volunteers have helped the National Park Service conduct a saguaro census, recorded habitat data on the climate-imperiled pika, and taken glacial core samples to track melting rates. Thousands of people venture into big-leaf maple habitats every day to hike, canoe, bike, ski, and snowshoe—why not have them collect a few tree samples while they’re at it?

Parker-Forney and Cronn hatched a plan: building on Cronn’s work for the Maple Fire case, they would create a comprehensive big-leaf maple database that law enforcement agencies could use to investigate thefts nationwide. Adventure Scientists would supply the volunteers, Cronn’s Forest Service team would analyze the data, and the WRI would provide the funding. But it wasn’t as simple as sending outdoor geeks into the field to geotag some leaves. In order for the database to be usable in court, the team needed to develop a standardized collection and analysis protocol with a clear chain of custody. The database would log each person who handled the specimens along the way, as well as the precise geolocations from which each specimen was taken. In just a few months, roughly one hundred and fifty Adventure Scientist volunteers collected specimens from 1,142 big-leaf maples in twelve distinct regions, more than enough to build a viable database.

Of course, big-leaf maples are not the only trees vulnerable to poaching. To curb the theft of other species, the Forest Service and Adventure Scientists are working on new databases for other species commonly stolen from public land, including western red cedar, Alaska yellow cedar, coast redwood, and black walnut. Parker-Forney hopes that this science might someday be of interest to international regulatory bodies. “We can go to the E.U. and say, ‘This is working,’ ” she told me. To that end, her team at WRI is developing another data collection partnership with the Forest Stewardship Council, an organization that certifies products as coming from responsibly managed forests.

In addition to expanding the range of sampled species, Cronn has even more ambitious hopes: to be able to test a board and determine its origin without the matching stump. This would allow regulators to establish whether a piece of wood was actually cut down where the seller claims, or whether it was felled in a protected area. They already have the samples, but need to retest them for different genetic and chemical markers. The finished project could dramatically affect the international logging trade. In this imagined future, the market for illicit timber would collapse. Poaching would simply be too risky.

Last December I visited Jacus in Quilcene. He took me to see an area of the Olympic National Forest that he’d been keeping his eye on, where a fallen Douglas fir had recently been carved up for firewood and where he suspected some big-leaf maple theft was about to occur. We headed south in his truck, which was rigged with a transistor radio, two long guns, and a computer mounted above the center console that resembled something out of Inspector Gadget. In a single mile, we gained enough elevation for the flatland rain to transform into cartoonish puffs of snow. The road followed the Dosewallips River, which ran clear and swift below us, edged with a magnificent thicket of trees whose branches reached skyward like gnarled fingers. They were dressed in thick coats of moss as bright as jewels and dusted with the freshly fallen snow, their branches curving and bowed as if mid-waltz.

We parked where a number of large rocks placed by the Forest Service had been rolled away to make room for a truck. A pickup had recently been spotted stuck in the drainage up ahead; he was sure it belonged to a local poacher. We plodded through new snow for a quarter mile until Jacus called my attention to one of the maples.

“See here?” he said, pointing to a six-inch patch of bark that had been scraped from the trunk. The marking was so small that I would never have noticed it, but it was big enough for a poacher to get a sense of the tree’s market value. As I leaned in to take a picture, he called out again.

“Here’s another one.” He was up the trail now, pulling back a patch of moss-covered bark from yet another maple, revealing the tree’s ruddy flesh. “Look how fresh this is,” he said. “That’s the early stages of a maple theft right there.”

Shortly after that trip, I volunteered to be an Adventure Scientist. I took a three-hour online course, which explained how to identify trees and collect samples. By this time, Adventure Scientists had finished collecting big-leaf maple samples and were now at work on black walnut, a species whose habitat spans thirty states east of the Rockies, and whose wood is far more valuable than even that of a big-leaf maple. A black walnut tree can live for two hundred years and grow to 120 feet tall, often crowding out its competitors by releasing toxic chemicals into the soil. Its attractive dark grain is coveted for furniture, gunstock, coffins, and veneer. Often, Cronn explained to me, black walnut is felled in the United States, sent overseas to be cut into strips of veneer, and then pasted atop furniture that is sold in the United States. During the pandemic, lumber prices soared because of supply-chain backups, making the poaching of trees like black walnut all the more lucrative. Today, lumber from a single black walnut tree can net $10,000.

A few months later, in February, I met with a group of recently trained Adventure Scientists in the east Texas flatlands some five miles from the Oklahoma border. In the parking lot of the Pat Mayse Wildlife Management Area campground, I was greeted by a group of seven volunteers led by Dennis Wilson, a retired conservationist. They all looked to be around sixty, drove pickups, and dressed in blue jeans and steel-toe boots (I had on a pair of clogs, which concerned them). The group knew one another well, as members of the Texas Master Naturalist Program, a local environmental association that conducted monthly projects. In preparation for the day’s outing, they’d taken the same training that I had, downloaded the app, and brought along the equipment that Adventure Scientists had shipped over: a coring tool, cardboard cylinders for storing the core samples, parachute cord, and baggies for collecting twigs and leaves. We hopped in the trucks, leaving my rental sedan behind, and headed into the woods.

The Pat Mayse Wildlife Management Area is an expanse of roughly nine thousand acres that, according to local legend, was created as compensation for a reservoir built in the Sixties to supply the nearby Campbell’s factory with water. Before it was protected land, it was used by the military as a firing range; bullets and casings riddled the trees and understory.

After about a mile we parked and traipsed into the heart of the forest, stepping high to avoid ankle-catching greenbrier. The week prior, Dennis had surveyed the area to locate black walnuts, and had set out orange ties near two trees not far from the road so we could find them again with ease.

“There it is!” someone called up ahead, pointing to a tree roughly eighty feet tall. Phyllis, one of the volunteers, opened the app and geotagged our location. Next we had to break off a twig sample, but the lowest branches were about thirty feet in the air. The training had suggested tying a rock to some parachute cord to knock off a small branch. The men tried it for about forty minutes, but none of their throws made contact. I gave it a shot, and my toss barely made it halfway up. In the end, we gave up and decided to find the other tree.

Thankfully the next black walnut had lower branches. As Phyllis wound the core sampler into the trunk like a corkscrew, the rest of us gathered a handful of fallen walnuts.

“Black walnut is edible,” Dennis explained, “but you need a serious hammer.” He broke one open with a rock. The cracked nut resembled the cross section of a brain. “My grandma used to pick these out,” Debra, the group’s president, recalled as she struggled to free bits of nut from the casing, “but it would take her days to get enough for a cake.”

Phyllis pulled out the corer to reveal a narrow glistening tube of black walnut trunk. We’d spent roughly three hours sampling a single tree, but as Cronn later explained, each sample was important—particularly those growing at the outer regions of a species’s range. These so-called edge samples tend to have unique genetic features, which help create a more accurate database for the entire species. “If we only sampled black walnut as far west as the Mississippi River,” Cronn told me, “trees from Kansas or Missouri would likely be predicted to originate in western Illinois.”

After we returned to our cars, Dennis indicated a black walnut that had fallen down on the edge of the lot. It was still fresh enough for a viable sample, and the naturalist suggested we could also cut some cookies—thin cross sections of the tree. These weren’t for the database, but would make pretty bits to varnish and display. Dennis got out the chainsaw and sliced flat rounds, handing one over to me as if it were a party favor. It barely fit into my suitcase. As I pulled it through airport security later that evening, I felt like some kind of poacher myself.

It was a nice keepsake that I could prop up in my backyard for decoration, but it was also worth something more concrete, I knew—a wood so pretty it could be milled into money. But the trees aren’t helpless. The sample I had stowed away held the key to its own defense: an embedded secret code. The scientists just needed to crack it.