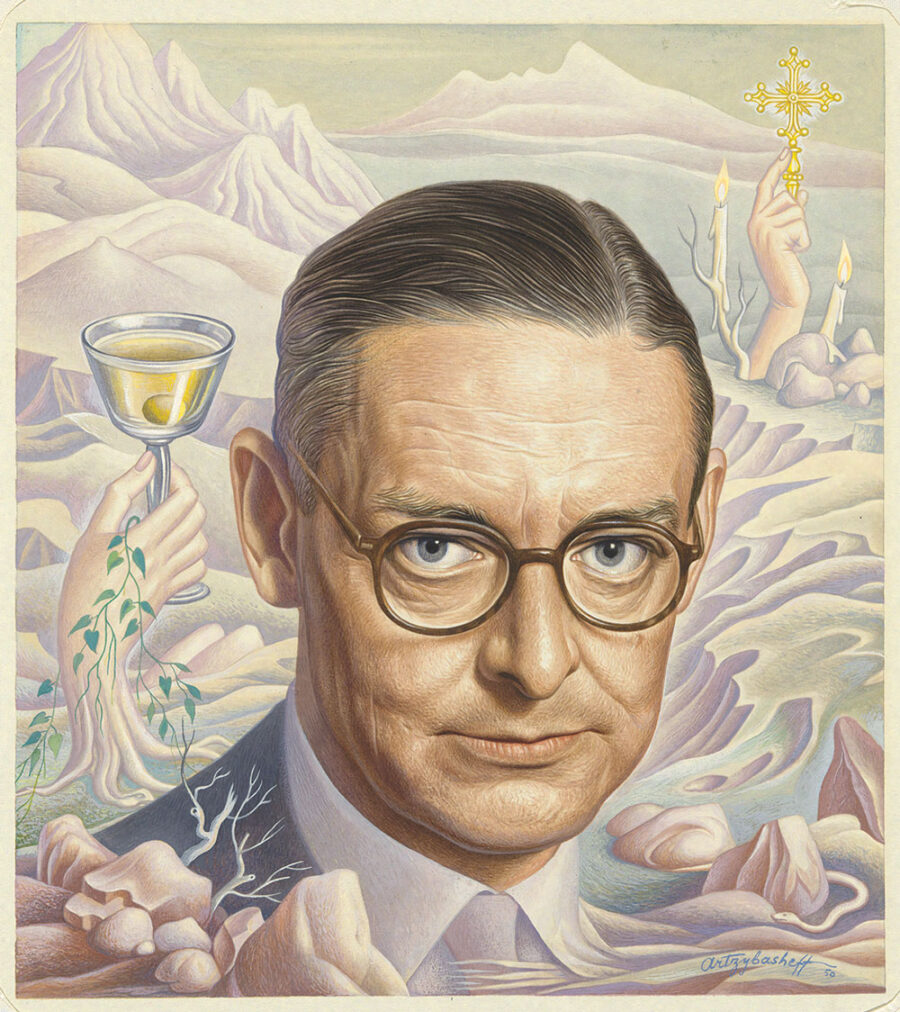

T. S. Eliot, by Boris Artzybasheff, from the March 6, 1950, cover of Time magazine. Courtesy Yale University Art Gallery, New Haven, Connecticut. Bequest of the artist

Discussed in this essay:

Young Eliot: From St. Louis to The Waste Land, by Robert Crawford. Farrar, Straus and Giroux. 512 pages. $35.

Eliot After The Waste Land, by Robert Crawford. Farrar, Straus and Giroux. 624 pages. $40.

In 1822, Percy Bysshe Shelley drowned, aged twenty-nine, in a sailing accident off the Italian coast. His cremation on a beach near Viareggio, which Lord Byron attended, later became the stuff of myth. Shelley’s poetry wasn’t widely read in his lifetime. It found a readership in an edition put together by his widow, Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley, with…