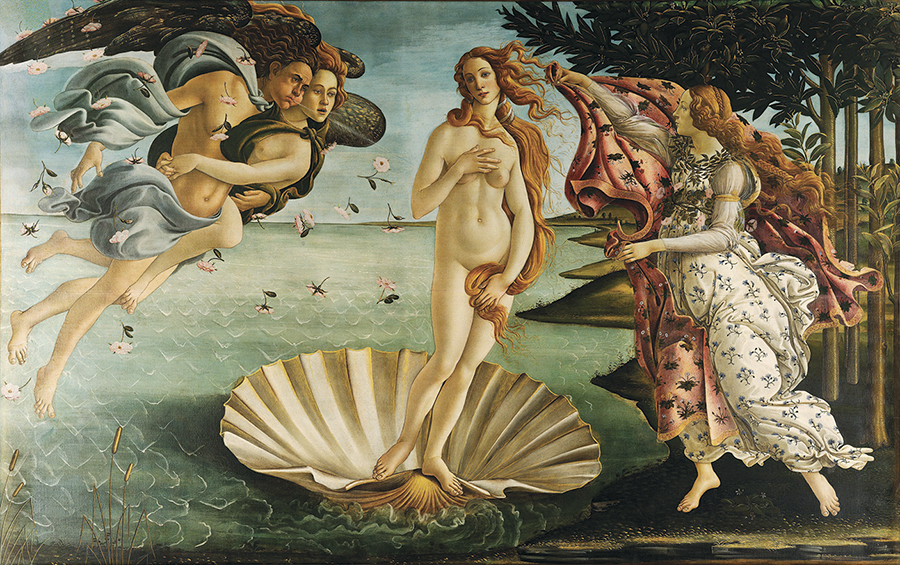

The Birth of Venus, by Sandro Botticelli. Courtesy the Uffizi Gallery, Florence

When telling a story, history’s imperfect record sometimes insists upon inconvenient gaps. This is the case with Botticelli’s illustrations of Dante’s Divine Comedy, a remarkable tale that spans centuries, countries, and players. Undaunted, Joseph Luzzi, a professor of comparative literature at Bard College, has undertaken the complex narrative with erudition and passion in his new book, Botticelli’s Secret (W. W. Norton, $28.95).

These religious illustrations are, as Andrew Butterfield put it, “among the most lively, tender, and psychologically searching works [Botticelli] ever created.” They were commissioned in the early 1480s by a member of the Florentine Medici family from an artist most famous today for the pagan masterpieces Primavera and The Birth of Venus. Botticelli worked on the drawings for well over a decade, but what happened next is uncertain, not least because he fell into obscurity before his death in 1510. Until the Victorian era, what little was known about the Renaissance artist came from Giorgio Vasari’s dismissive account in Lives of the Most Excellent Painters, Sculptors, and Architects.

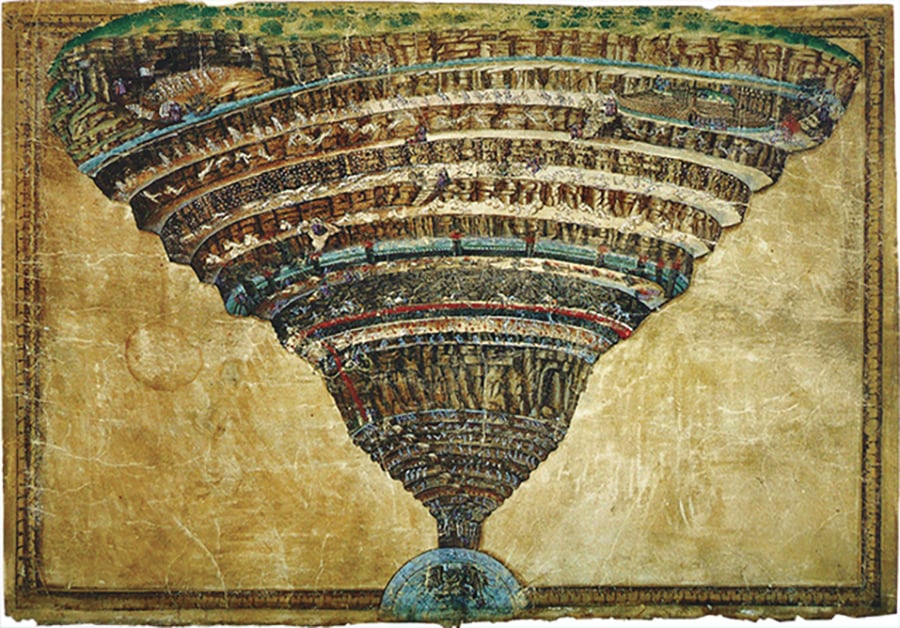

The drawings’ fate remains a subject of debate. Luzzi proposes that they were given to Charles VIII of France as a “ravishing present” after his invasion of Florence in 1494. It is certain that, in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, the bulk of the drawings were in France, in the hands of the bookselling Molini family, and were sold to the Scottish Duke of Hamilton in 1803. (A small cache of eight drawings, including the extraordinary The Map of Hell, were separated early on from the larger collection and came into the possession of Queen Christina of Sweden: after her abdication in 1668, she took them to Rome, where they remain today housed within the Vatican Library.)

From 1540 onward, with one (inaccurate) exception, “nobody had even referenced the drawings in passing” until the art historian Walter Pater wrote about them in his 1873 Studies in the History of the Renaissance. He restored Botticelli’s work to prominence, lauding him alongside Michelangelo and Leonardo da Vinci. Regarding the Dante illustrations, he “found Botticelli to be more humane and magnanimous than the poet he was illustrating.” Along with his fellow Oxford University tutor John Ruskin, the Swiss art historian Jacob Burckhardt, and the pre-Raphaelites, Pater fostered “the Victorian cult of Botticelli.” At the height of the artist’s revival, in 1882, Friedrich Lippmann, a director at the Royal Museum of Berlin, purchased Botticelli’s Dante drawings for the museum’s collection, offering eighty thousand pounds (roughly seven million dollars today) to the Hamilton family.

Since this rediscovery one hundred and forty years ago, the illustrations have been central to our conception of the Renaissance and, Luzzi argues, our understanding of Botticelli as an artist willing

to toil, in the margins of his career and while working on higher-profile commissions, on an ambitious plan to illustrate a Christian poem whose scholarly rigor challenged him aesthetically, intellectually and morally.

This exhilarating story constitutes the second half of Luzzi’s book. The first provides us with a biographical account of Botticelli and fills in his broader cultural context, beginning with that of his fellow Florentine, Dante Alighieri (1265–1321), whose lasting importance in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries (including on writers like Petrarch and Boccaccio) made him “his native city’s cultural patron saint.”

Luzzi’s ambitious book walks a careful line between academic rigor and accessibility, and vividly renders many distinct characters. He is not above chummy contemporizing locutions—he notes the “key” for artists in the fifteenth century was to create “a visual ‘brand’ ”—but he is careful not to sacrifice the story’s complexity. That said, he offers little substantive analysis of the drawings themselves, or of Botticelli’s intentions: in the absence of textual evidence, the case for Botticelli’s aforementioned intellectual rigor remains scant.

Replete with unexpected twists and dangling threads, the trajectory of Botticelli’s Dante illustrations nonetheless becomes, in Luzzi’s telling, a story about the force of art to shape lives. In a moving epilogue, Luzzi describes his own visit to the Vatican Library to see The Map of Hell, and relates how the “precise, painstaking details” of the original—“the scoring of the parchment, the tiniest of features and gestures in the sinners, the varying hues and shades within the individual colors”—allowed it to surpass its many reproductions.

The Map of Hell, by Sandro Botticelli. Courtesy the Vatican Library

Lion Feuchtwanger’s novel The Oppermanns (McNally Editions, $18), in the original translation by James Cleugh, with contemporary revisions and an introduction by Joshua Cohen, tells the story of a prosperous Jewish family in Berlin during the rise of the Third Reich. The novel was first published in the Netherlands in 1933. The “precise, painstaking details” that Luzzi sees in The Map of Hell are powerfully present in The Oppermanns: the characters may be fictional, but the novel hews closely to the actual events of the swift and brutal Nazi takeover. Feuchtwanger himself had fled to France, but as Cohen points out, he wrote

as the events he was writing about were still unfolding, and even while he was suffering the same tragedies as his characters: in 1933, his property in Berlin was seized; his books were purged from German libraries and burned; he was banned from publishing in the Reich; and he was stripped of his German citizenship.

Feuchtwanger eventually escaped to the United States with the help of, among others, the remarkable Varian Fry (who, with his Emergency Rescue Committee, assisted thousands, including André Breton, Max Ernst, and Marc Chagall), and settled in Pacific Palisades, near his compatriots and fellow novelists Thomas and Heinrich Mann. Bertolt Brecht was also a good friend: “Like Brecht,” Cohen notes, “Feuchtwanger expected his work not just to be something, but also to do something.” And yet, even large international sales of The Oppermanns failed to achieve Feuchtwanger’s aim to awaken a broad resistance.

The novel opens with Gustav Oppermann, the eldest of four siblings, on his fiftieth birthday, awakening in his villa in Grunewald. “In the profound silence that precedes daybreak, he breathed the forest air deeply and with enjoyment,” Feuchtwanger writes. “The strokes of an axe came faintly from the distance; he liked the sound; the rhythmic blows emphasized the stillness.” Even in this moment of pleasure, the omens are dark. Co-heir to a successful furniture business, Gustav leads a comfortable life of intellectual pursuit (he is at work on a book about the Enlightenment writer Gotthold Ephraim Lessing), romantic pleasure (he keeps a lovely young mistress), and social prominence. At fifty, “he really was doing well. Physically, materially, and spiritually.”

This illusion of safety cannot endure. The novel charts the National Socialists’ anti-Semitic pressures across various fronts, including the Oppermann furniture business (which Gustav’s brother Martin scrambles to protect by changing its name) and Martin’s son’s education at the Queen Louise School, where a vindictive new master has the Jewish boy in his sights. Over three sections titled “Yesterday,” “Today,” and “Tomorrow,” Feuchtwanger delineates—with what was, at the time, agonizing prescience—the ever-darker unfolding of the Reich’s repressive mission, resulting in a novel at once unbearable and unputdownable. It is also an alarmingly timely reminder: the Nazis’ first steps—censorship, disinformation, and the sowing of fear and mistrust among citizens—in turn permit the unspeakable. In his introduction, Cohen makes an impassioned plea for Feuchtwanger’s masterpiece:

Given that Feuchtwanger’s books were so explicitly and accessibly addressed to a general audience, I’d be remiss not to mention that he has none now—that he has no audience but us. His novels go unread; his plays go unperformed; he’s a first-class writer without a first-class berth.

The exhortation that we read this book is as urgent as Feuchtwanger’s need to write it. Both cite a Talmudic saying attributed to Rabbi Tarfon: “It is not your duty to finish the work, but neither are you free to neglect it.” Cohen insists that “it is not your duty to finish this novel, but neither are you free to neglect the history it preserves with such artistry, agony, and passion.” The effect of Feuchtwanger’s recurring use of the phrase, Cohen suggests, is to propose: “Tell me what ‘the work’ means to you, and I’ll tell you who you are.”

Photograph © Marc Wilson

The writer Constance Debré might well have taken this statement to heart. The daughter of a prominent French family (her paternal grandfather was prime minister; her father a celebrated journalist; her maternal grandfather a politician in Pétain’s Vichy government), Debré was herself a successful lawyer for years. In 2015, however, she made a series of radical changes to her life. Not only did she leave her husband, come out as a lesbian, and alter her physical appearance, she also quit her legal practice to become a full-time writer, thereby abandoning financial security and the trappings of a bourgeois life. Her award-winning 2018 novel Play Boy is the autofictional account of her coming out. Her new book, Love Me Tender (Semiotext(e), $17.95), admirably translated by Holly James, continues to trace her psychic and sexual evolution, while also describing the agonizing impact of her decisions on her relationship with her son, Paul.

This brief, intense novel opens with a meditation that appears at first offhand—“I don’t see why the love between a mother and son should be any different from other kinds of love,” the narrator muses—and perhaps willfully cold. But it reveals itself, as the narrative unfolds, to be a character grappling with grief. Near the novel’s end, the narrator relays a moment of revelation: “It was yesterday, while I was riding my bike, that. . . . I realized that the sadness was over. . . . I realized I’d finished grieving for my son.” Whether this is true or a momentary belief, it recasts the narrator’s opening assertion as defensive, fraught, the statement of a character striving mightily for authenticity and honesty, questioning and rending—pace Camus—the veil of social norms, acknowledging the Absurd, in hopes of finding some more solid, albeit subjective, truth. “For me,” she says, “homosexuality isn’t about who I’m fucking, it’s about who I become. With men there was always a limit, now I have all the space I want, I feel like I can do anything.” And yet that space and freedom come at considerable cost.

The urgency of Debré’s account—in which she moves from one precarious living situation to another and records her various sexual encounters with insistent detachment—arises both from the philosophical sincerity of her endeavor, and from justified bafflement that what seem straightforward steps toward a more truthful existence should be so aggressively punished by society. While at the novel’s outset her ex-husband Laurent still hopes for reconciliation, he quickly becomes vindictive, impeding her access to their eight-year-old son. “Since November, Paul’s been staying with his dad, I don’t see him anymore,” the narrator records. “Every time I propose something, Laurent either refuses or doesn’t reply. . . . I don’t threaten to take him to court, I don’t want to make things worse.”

The narrator’s daily life is punctuated by an intense swimming regimen, by the banal practicalities of where to sleep and how to eat, and by an almost monastic devotion to sex. Rather like Mickey Sabbath, the protagonist of Philip Roth’s Sabbath’s Theater, who described himself as “a Monk of Fucking,” she observes:

I’m learning that I can love anyone, desire anyone, come with anyone, be bored with anyone, hate anyone, I’m learning that there’s a fine line between loving and not loving, I don’t see why it’s such a big deal, I don’t see why it should have to be anything more than that, just love, just desire. Why all the drama? That’s what I’ve been wondering.

The novel raises this salutary question, even as it describes that inescapable—and painful—drama. Through the courts, and the inefficient bureaucracy of the state, Laurent stymies her attempts to see Paul for an unconscionably long time. Even after supervised visits are under way, and longer outings are finally allowed, Paul’s presence is erratic. These travails aren’t tidily resolved by the book’s end. Debré comes to recognize that “we’re one big family, those of us who walk out and end up losing our kids,” and, in growing resigned to the loss of her intimacy with Paul, she is able at last to forge a romantic connection with her lover: “It was when I decided to stop thinking about Paul all the time that things started moving forward with her.”

Debré’s book portrays the high cost of principled choices: even now, in Paris, in a condition of relative privilege, endeavoring to live honestly and openly results in profound suffering. Late in The Oppermanns, after one of the central characters has paid for his principles with his life, others discuss striking the right balance between idealism and pragmatism. “Common sense. Nothing else counts,” says one. “And Socrates? Seneca? Christ?” asks Gustav. “Were their deaths useless?” To which the younger man, educated in the brutal Nazi reality, replies, “It is wiser to live for an idea than to die for it. . . . It is mere folly to put on the airs of a martyr nowadays.” Debré might beg to differ; and we should celebrate the fact that, despite her hardships, she still has the luxury to do so.