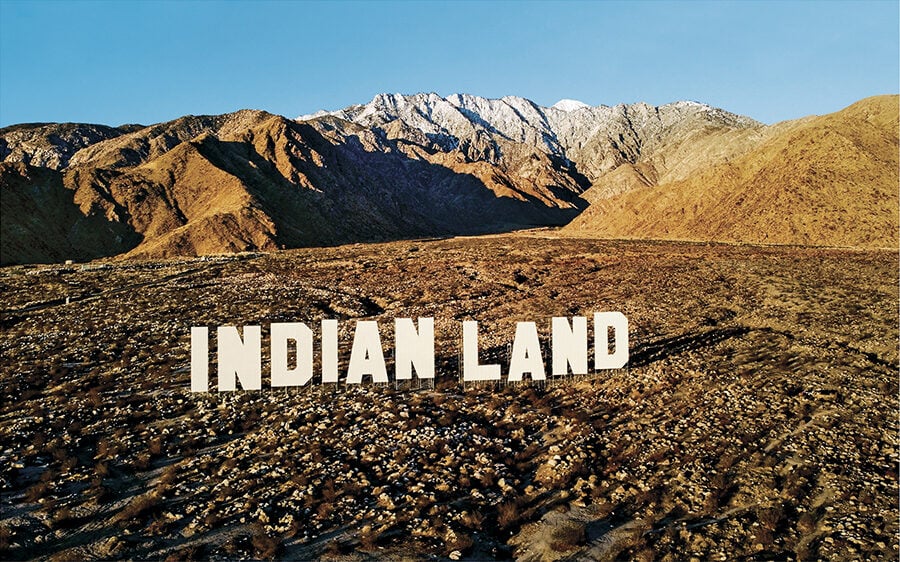

“Never Forget,” by Nicholas Galanin © The artist. Courtesy the artist and Peter Blum Gallery, New York City. Galanin’s work is on view this month at the Van Every/Smith Galleries at Davidson College, in North Carolina

Discussed in this essay:

Indigenous Continent: The Epic Contest for North America, by Pekka Hämäläinen. Liveright. 576 pages. $40.

In the 1630s, the powerful Pequot Confederacy of southern New England found itself beset by enemies. English settlers had recently arrived and were joining with the Pequots’ Indigenous rivals. Soon, tensions over the fur and wampum trade led to war. The fighting reached a climax when the British and their allies besieged a Pequot fort and set it aflame, hunting down those who fled. It was among the bloodiest massacres in North American history, one that experts have described as genocidal. At least three hundred Pequots, including noncombatants, died that day (credible estimates reach seven hundred). The few left alive—the war and massacre had killed perhaps as many as two thirds of the Pequots—were scattered, many sold into slavery. “A nation had disappeared from the family of man,” wrote the nineteenth-century historian George Bancroft.

Yet the Pequots persisted and, eventually, rallied. Today, you can learn their story at the Mashantucket Pequot Museum and Research Center in Connecticut, a gleaming $225 million edifice—roughly the same size as the Tate Modern in London—that the Pequots built. It looks onto Foxwoods Resort Casino, which the Pequots also own. Foxwoods made the Pequots the richest tribe in the country for a time, and by 1998 many members were earning more than a quarter of a million dollars a year from it. “They are rich and powerful,” a lawyer for the Pequots explained; they “can do what they like.”

Powerful Native Americans doing what they like isn’t the standard story. Indians (the term is widely though decreasingly used by Native peoples) fill the pages of most American histories, but usually only in the early parts. By the twentieth century, they tend to shuffle off the stage, having lost their lands and lives. Indigenous peoples once lived here, now they don’t—so goes the myth of the “vanishing Indian.”

That myth always rang false, but never more than now. The federal government recognizes 574 tribal nations, and reservations collectively cover an area the size of Idaho. Since 1960, the population identifying as Native American has multiplied almost twentyfold from about half a million to ten million. It nearly doubled between 2010 and 2020 alone. The recent growth stems not from rising birth rates or life expectancies but from an increased desire among those with Native ancestry—and sometimes without it—to claim this identity. Although Native peoples still face the worst poverty rate in the country, energy sales and gaming have brought conspicuous prosperity to some. There is, the Ojibwe writer David Treuer has observed, “a sense that we are surging.”

As Indigenous peoples have grown more numerous and visible, academics have attacked the “vanishing Indian” narrative. Since the Seventies, historians, including Native scholars, have shown much greater interest in seeing the past through Indigenous eyes. For some, this means exposing the violence of Native dispossession, showing that Native Americans didn’t obligingly ride off into the sunset. But for other scholars, and especially recently, it means challenging the victim narrative and stressing Native power.

A central figure in this school is Pekka Hämäläinen, a Finn with a doctorate from the University of Helsinki. His first book, The Comanche Empire, published in 2008, maintained that, rather than being subjugated themselves, Comanches built a violent empire, led by “protocapitalists,” that subjugated Europeans on the mid-nineteenth-century southern plains. It was fresh, powerfully argued work—“one of the finest pieces of scholarship that I have read in years,” wrote the reviewer for the leading journal in early American history—and its many awards included the vaunted Bancroft Prize. It also secured Hämäläinen the Rhodes professorship in American history at Oxford University, making him arguably the highest-placed historian of Native America.

Hämäläinen’s next book, Lakota America: A New History of Indigenous Power (2019), painted a similar portrait of the Lakotas. Now comes Indigenous Continent: The Epic Contest for North America, his grand overview of Native history from the fifteenth century onward. It is a provocative book, taking Hämäläinen’s previous arguments and raising their volume. Yes, Europeans established North American colonies, Hämäläinen writes, but their “outlandish imperial claims” were often mere cartographic fictions. Well into the nineteenth century, the continent remained “overwhelmingly Indigenous.” And it did so because Native peoples, rather than being docile innocents, were formidable fighters who for centuries held the world’s most powerful empires at bay.

Indigenous Continent raises a pressing question: How best to tell the story of oppressed peoples? By chronicling the hardships they’ve faced? Or by highlighting their triumphs over adversity?

In writing African-American history, it was once common to foreground revolts, resistance, cultural achievements, and hard-won victories, as in Taylor Branch’s prize-winning three-volume history of the civil-rights movement. Such themes still resonate, but the trend today is toward grim accounts of unyielding oppression. The New York Times’s 1619 Project described enduring continuities between the days of slavery and the present. Emancipation, in the eyes of the influential theorist Saidiya Hartman, wasn’t “liberation” but merely a “transition” from one type of subjugation to another. Hartman’s former student Frank B. Wilderson III, a founder of the Afropessimism school of thought, puts it more starkly. “Blackness cannot exist as other than Slaveness,” he writes. Anti-black racism runs so deep, Wilderson insists, that to imagine black people free would be to imagine “the end of the world.”

You can find similar outlooks on Native history. “North America is a crime scene,” argues Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz in An Indigenous Peoples’ History of the United States, a popular recent overview. “Somehow, even ‘genocide’ seems an inadequate description for what happened.” Genocide is now a familiar charge in reference to Native Americans. Another is “settler colonialism,” an especially totalizing form of empire that seeks not to rule subjugated populations from afar but to “permanently and completely replace Natives with a settler population,” as the Lakota scholar Nick Estes writes in Our History Is the Future. “Indigenous elimination” is “the organizing principle” of the United States, a country that, Estes maintains, possesses a “death culture.”

Such bleak views are understandable, given all that Native peoples have endured. First came the European diseases, which started their work even before the colonizers’ settlements took root. (When the Pilgrims met Squanto in 1621, his community had already been wiped out by diseases from European ships plying the North American coast.) Then came the killing—centuries of it—sometimes as war and sometimes as outright massacre. The United States government alone counted 1,642 military engagements against Indigenous adversaries. By the time those conflicts ended at the turn of the twentieth century, the Native population of what is now the contiguous United States had dropped from perhaps five million at European contact (estimates vary widely) to under two hundred and fifty thousand.

Deny any of this and you’re whitewashing. Yet focusing solely on death and despair might not be right, either. Accounts of the settler-colonial steamroller play into the colonizers’ sense that conquest was inevitable, coming perilously close to replicating the vanishing Indian myth. And they leave little room for the richness of Native societies. “I want—I need—to see Indian life as more than a legacy of loss and pain,” Treuer writes. Indians can’t just be “ghosts that haunt the American mind,” defined by all that’s been taken from them.

In recent histories, they’re not. At a time when stories of stark oppression are on the rise, Native American history has largely gone the other direction. So while, in public, talk of genocide and settler colonialism is common, in history departments, the trend is toward exploring Indigenous autonomy and control. Some historians are wary of the widespread application of the “settler colonialism” concept, given how ineffective early European attempts to displace Native societies were. “Settler colonialism may be at most a minor theme for continental North America” until the middle of the nineteenth century, the historian Jeffrey Ostler writes.

Hämäläinen refers to settler colonialism only a handful of times in his three books. His abiding interest is instead in Europeans’ inability to colonize North America. In his first two books, he explored notable peaks of Native power, as many recent histories do. But now, with Indigenous Continent, he stitches them into a sustained counterpoint to the conquest narrative. Five hundred years of North American history appear in his telling not as the story of colonization, but of a fierce and unsettled continent, bristling with possibility.

Not all of the Americas held out against conquest. South of the Rio Grande, the Spanish encountered large Indigenous empires: the Maya, the Incas, and the Aztecs. These proved “remarkably easy” to vanquish, Hämäläinen writes. Native civilizations “fell like dominoes” because once Spanish conquistadors used their “technological edge” to subdue Indigenous rulers, those rulers’ vast territories and extensive tributary networks fell in line. Hierarchical structures made the largest American empires easy prey.

But things were different farther north. In the land currently covered by the United States, colonizers encountered “dangerously decentralized” societies. The “genius of their political systems” was that they didn’t have hierarchies for Europeans to seize. “Too many of the Native Americans were nomads and hard to pin down.” Rather than winning a few battles or co-opting a few leaders, colonizers would have to take North America acre by acre.

It can seem, reading conventional histories, as if they did so easily: settlers arrived with guns, coughed a few times, and made short work of any remaining Indians they encountered. However, “Native power” historians like Hämäläinen have noted that this familiar narrative only works if you skip lightly over early centuries and ignore most of the continent. Get time and space in proper perspective, and things look different.

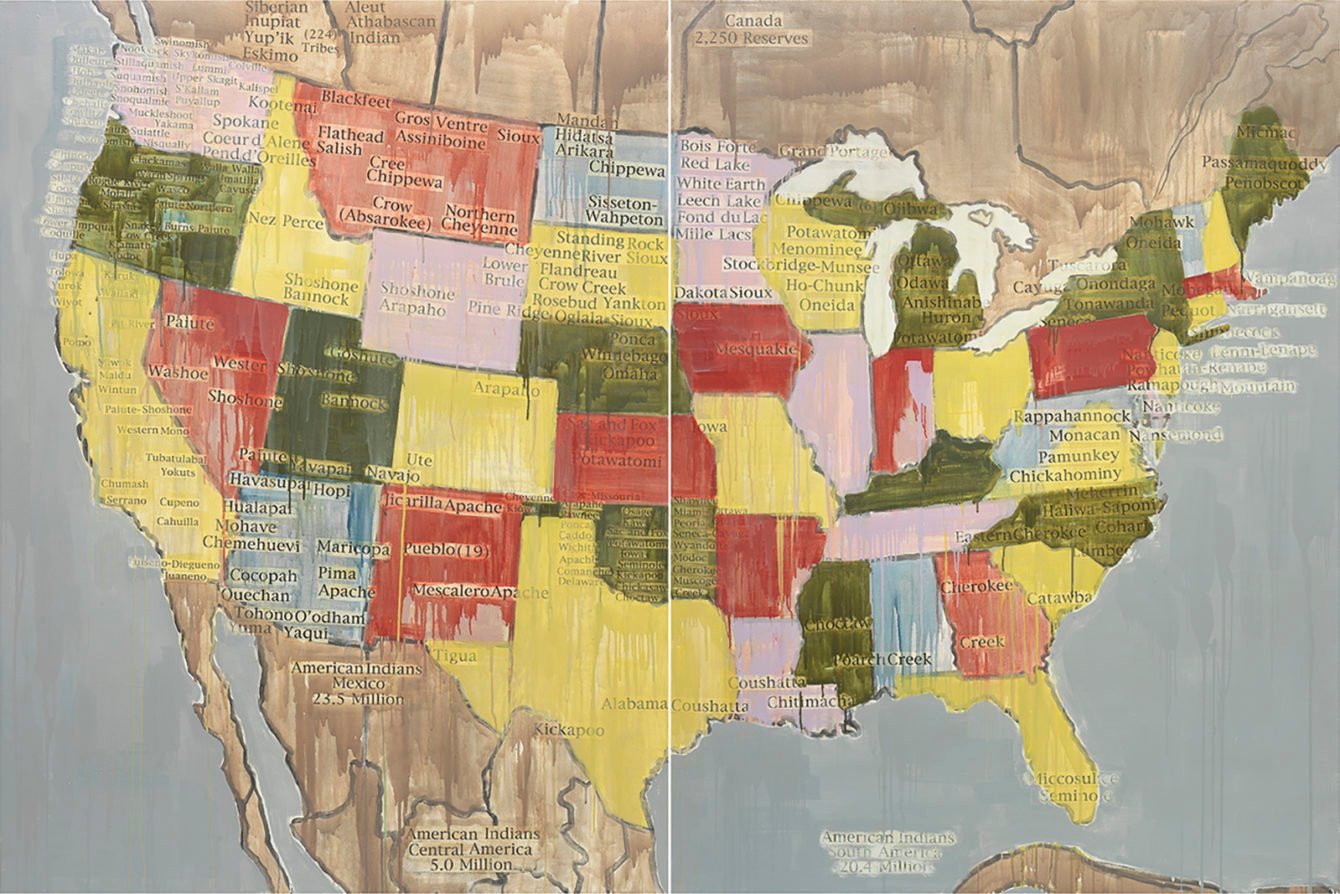

The map certainly does. Most histories of North America deal solely with the locales where Europeans lived. So, early American history is “colonial history”—never mind that little of North America was “colonial” then—and starts with Jamestown and Massachusetts. The Great Plains enter the picture only in the late nineteenth century, with the coming of transcontinental railroads. By spatially conflating American history with settler history, such histories push the places where Indigenous peoples lived to the blurry background.

“Native power” historians rightly insist that American history must deal with the full map—starting by replacing “colonial history” with “continental history,” as Michael Witgen puts it. So, for example, what happened in 1776? That was when colonists on the eastern seaboard sought to end their subordination to the British monarchy. But for much of the continent, such developments meant little. Hämäläinen is more interested in another event of the time: the founding of the modern Lakota nation at present-day South Dakota’s Black Hills, which the Lakotas, bearing guns and riding horses, seized and claimed as their sacred homeland. This, he writes, was “one of the most consequential moments in North American history,” marking the inauguration of a massive land empire.

Did Europeans even know of it? On published maps, the Black Hills were a European possession, owned by the Spanish and the French until they passed via the Louisiana Purchase to the United States. On the ground, however, this was risible—there were no Europeans to be found. When Thomas Jefferson sent Meriwether Lewis and William Clark to explore the territory he’d recently bought, they were “navigating an Indigenous world that they understood only dimly,” Hämäläinen writes, and in their naïve stumbling nearly got themselves killed by Lakotas. Hämäläinen and other historians use Lakota winter counts, pictographs drawn annually onto buffalo hides (and sometimes paper), to reconstruct the politics of the Native interior. They have to, as pen-wielding settlers were far away and often clueless about major historical developments on the continent they claimed to own.

Traditional histories don’t have a place for Lakotas on their maps, nor do they make room for Indigenous peoples on their timelines. Although Europeans have been a continuous presence in the Americas since the fifteenth century, most American history fast-forwards through the early centuries, treating the era before 1776 as prelude.

Again, the effect is to minimize Indigenous power, as those were the centuries when settlers were bunched up on the edges of North America and Native peoples had the run of the vast interior. Play back the tape at normal speed, and you see how long Europeans were confined to narrow areas and how halting their expansion was.

By Hämäläinen’s clock, it took some four hundred years from Christopher Columbus’s arrival before any colonizing power “subjugated a critical mass of Native Americans” in North America. That power was the United States, extensive in its reach yet late in its arrival. The country still hasn’t existed for even half the time that Europeans have been on the continent. “On an Indigenous timescale,” notes Hämäläinen, “the United States is a mere speck.”

Tribal Map, by Jaune Quick-to-See Smith © The artist. Courtesy Garth Greenan Gallery, New York City

In considering the whole map and the whole timeline, Hämäläinen is doing similar work to other historians of Native America. In other ways, however, he goes further. Hämäläinen is particularly interested in terminology. Too often, conventional vocabulary has conspired to quietly diminish Indigenous politics. Descriptions of people living in tribes, dwelling in villages, following the guidance of chiefs, and sending forth braves to fight seem quaintly out of step. Hämäläinen uses different language. Indigenous people, in his writing, belong to nations, live in towns, are governed by officials, and fight with armies and soldiers. Controversially, Hämäläinen describes the largest Indigenous groups as empires bent on hegemony. In Indigenous Continent he uses the twentieth-century term “superpower.”

Not all agree. “This is post-modern cultural relativism at its worst,” Estes has written of Hämäläinen’s Lakota America. Jameson Sweet, a Lakota and Dakota historian, rejects the idea that the Lakotas constituted an empire and sees them, rather, as “a desperate people trying to survive and adapt to a turbulent world brought on by settler colonialism.” In casting Native societies as imperialists, Hämäläinen arguably relieves Europeans of culpability—what was their sin, other than succeeding where their Indigenous rivals failed?

Such criticisms, which have come especially from Lakota historians, have not fazed Hämäläinen. Indigenous Continent presents an amped-up version of his earlier work’s argument, Tarantino-like in its taste for Indigenous power and violence. Native people are indomitable badasses: cunning, tactically brilliant, and terrifying to their enemies. Europeans, by contrast, mostly appear as hapless blunderers.

Sustaining such a judgment requires a heavy thumb on the scale. When the settlers’ colonies are small, it is because they are “cramped” and “curbed” by powerful Natives. Yet when Indigenous polities are small they are “nimble,” using their size as clever “camouflage.” Similarly, when the Iroquois trade with their rivals, this shows the “genius of Iroquois foreign policy”: a “principled plasticity” that allows them to navigate choppy political waters. When the French do the same, it shows that they are weak and reliant on Native peoples for survival.

Discussing the Lakotas, Hämäläinen describes their eschewal of central coordination as a “sophisticated governing system” that allowed them to “keep their power hidden from outsiders.” But when United States settlers acted independently of their central government, it merely reveals that their country was “poor and weak” and “had failed” (an “administrative and military midget,” is how Hämäläinen describes the post–Civil War United States in Lakota America). Native people who make war without the sanction of higher authority are shrewdly exercising decentralized power. Settlers who do the same are “vigilantes” and “thugs.”

Nearly everything, in Hämäläinen’s world, can be interpreted as a sign of settler incapacity, especially if you read violence—at least, when perpetrated by Europeans—as stemming from insecurity. When settlers make their first territorial incursions, Indigenous societies are “carefully steering the Europeans’ course.” When settlers strip Native people of rights and refuse to speak their languages, it’s “spawned by fear and a sense of weakness.” When they win a bloody war, it’s “a sign of weakness, not strength.” Pushing Indigenous peoples off their land onto reservations is also “a sign of American weakness, not strength.” And when the Seventh Cavalry of the U.S. Army mows down at least two hundred and seventy Lakotas at Wounded Knee? “A sign of American weakness, not power.”

Hämäläinen uses the word “weakness” twenty times to single out settlers—and just once to single out Native groups. The problem isn’t the verbal repetition; it’s the analytical flatness. Even when Europeans win wars, they’re weak, and, even when Indigenous peoples lose them, they’re strong. By 1850, state-backed settlers had expelled three quarters of Native Americans living east of the Mississippi from their lands and started a series of exterminatory campaigns on the West Coast. Hämäläinen, more taken with the nomadic holdouts on the Great Plains, judges the mid to late nineteenth century to be the time when “Indigenous power in North America reached its apogee.”

The subtitle of Indigenous Continent is “the epic contest for North America.” In Hämäläinen’s view, it was a contest, not a conquest, and the sides were, if not evenly matched, then at least competitive. “Nothing in America was preordained,” he writes.

Challenging the inevitability of European expansion has been understandably important to scholars. That’s because colonizers frequently insisted that their attacks on Indigenous societies were merely the unspooling of destiny. Native peoples were doomed by a “law of nature,” Thomas Jefferson believed. Such views encouraged genocidal campaigns by relieving white people of their compunctions. If the universe itself was arrayed against Indigenous survival, who were the colonists to fight fate?

Scholars have shown, contra Jefferson, that the supposed sources of European dominance didn’t confer decisive advantages—or at least not immediately. Colonizers arrived in America bearing “guns, germs, and steel,” as Jared Diamond has memorably written, but they started “losing their technological edge” quickly, Hämäläinen rightly notes. Although Indigenous nations didn’t manufacture guns, they nevertheless acquired them. Hämäläinen describes how Comanches plundered Spanish and Mexican ranches, sold the loot and captives through their extensive trading network, and turned their homeland into a horse, slave, and weapons depot. Their claims didn’t appear on European maps, but well-armed Comanches “carved out a vast territory that was larger than the entire European-controlled area north of the Rio Grande at the time,” Hämäläinen writes.

Neither did diseases decide the issue as conclusively as we often suppose. Native peoples initially lacked defenses against European pathogens, that’s true. Yet they had time to rebuild their ravaged societies and develop resistance—the diseases they suffered later were often caused by harsh living conditions as much as by pure contagion. On the other side, the colonizers weren’t exactly paragons of health. A smallpox epidemic during the American Revolution “took many more American lives than the war with the British did,” the historian Elizabeth Fenn has written. Indigenous peoples suffered from diseases more than settlers did, but to suggest that European conquest was merely the work of microbes defies much of what we know.

A video still of the Mirror Shield Project by Cannupa Hanska Luger. From an action at Oceti Sakowin Camp, Standing Rock, North Dakota, November 2016 © The artist. Courtesy Garth Greenan Gallery, New York City. Documented by Rory Wakemup

So what does explain eventual European dominance? More than in Hämäläinen’s first book, Indigenous Continent soft-pedals settler success, so he doesn’t tackle the question head-on. Yet reading his new work, one source of the colonizers’ strength jumps out: there were just more settlers than Native people.

A lot more. While French and Spanish populations in the Americas grew at normal rates, the Anglo populations—enjoying congenial climates and the backing of energetic British markets—exploded. By the middle of the eighteenth century, Benjamin Franklin observed that, astonishingly, the number of British colonists was doubling every twenty-five years. This was a “rapidity of increase probably without parallel in history,” wrote the economist Thomas Malthus. Immigration played a part but so did birth rates, as Franklin well knew. He was his father’s fifteenth child, and there were two more born after him.

This doubling rate held, and the land covered by today’s contiguous United States soon filled with Anglos. Already in 1800, U.S. citizens and enslaved people outnumbered Indigenous people nine to one. A century later, it was 320 to one. “Count your fingers all day long,” the Mdewakanton Dakota leader Little Crow remarked, “and white men with guns in their hands will come faster than you can count.”

The volcanic burst of settlers puts Hämäläinen’s narrative in perspective. Hämäläinen describes the Comanches as “the pinnacle of Indigenous power in North America.” At the “zenith of their power” in the late 1840s, he writes, there “may have been as many as twenty thousand.” Which means their whole empire was then smaller than the canal port of Troy, New York. And the mighty Lakotas, whose late-nineteenth-century military victories represented the “culmination of a long history of Indigenous power in North America”? They never exceeded fifteen thousand. By the time of their defeat in 1890, there were well over four thousand settlers for every Lakota.

Hämäläinen observes that Indigenous peoples could still sometimes triumph on the battlefield. Yet these conflicts had an important asymmetry. Native powers faced existential threats to their homelands and mustered extraordinary proportions of their populations. For the United States, however, these were frontier skirmishes. Indigenous forces could win battles, as when a western alliance famously wiped out George Custer’s men at Little Bighorn in Montana Territory. But, contrary to Hämäläinen’s claim that Native adversaries brought the United States “to the breaking point again and again,” there was no chance that they’d take Chicago, Boston, or any other major city. To conclude from Custer’s defeat that the Plains Indians were a superpower on par with the United States is like inferring from recent events in Afghanistan that the Taliban’s military must be among the world’s most powerful.

The Sauk leader Black Hawk, who fought the United States in present-day Illinois and Wisconsin, learned this lesson the hard way. Seeing only the outer edges of U.S. power, he was confident enough to march what Hämäläinen calls “a multinational army of eleven hundred soldiers” against the United States in 1832. Yet after his defeat and capture, Black Hawk was taken east, where he gained a humbling new perspective. “I had no idea that the white people had such large villages, and so many people,” he gasped. “Our young men are as numerous as the leaves in the woods,” Andrew Jackson told him. “What can you do against us?”

Hämäläinen acknowledges the demographic dominance of settlers, yet time and again he returns the focus to land. Seven of his chapters end with a reminder of how much of it remained in Native hands. In this he resembles the Republicans who point to county-by-county electoral maps to show the strength of conservatism. Such maps feature islands of blue in seas of red. This is misleading for the simple reason that it’s not land that counts, it’s people. Similarly, Hämäläinen’s acreage obsession risks overstating the “persisting Indigeneity” of North America by conflating holding land with holding power. Even today, the bulk of American Indians live in rural areas and small towns; they are spread out widely. But, now as then, living rurally doesn’t always mean you’re calling the shots.

Hämäläinen is right that European expansion was slow and unsteady, more so than colonizers liked to admit. And he’s right that European arms and pathogens did not wipe Indigenous nations off the map. But given the staggering growth of the Anglo settlers, is it at all surprising that even the most adept Native armies eventually lost their wars? White settlers arrived like a force of nature, a “cyclone,” as the Potawatomi writer Simon Pokagon put it in 1893. He imagined Indians as standing fixed to the shore while “the incoming tide of the great ocean of civilization rises slowly but surely to overwhelm us.”

Pokagon’s sense of North American history, offered in his published talk, The Red Man’s Rebuke, is virtually the opposite of Hämäläinen’s. For Pokagon, Native America was sculpted by settlers, who, rather than carving out a place for Indigenous life, had “hacked to pieces and destroyed” it. For Hämäläinen, Native peoples survived intact—and, indeed, were often the ones doing the sculpting. Which is right? Is the real story how Indigenous peoples have been pushed down, or how they have risen up?

Surely it’s both. Write only about the rigid structures of oppression and you expunge any sense of possibility. But dwell too much on the agency of the oppressed and you do the opposite: you fail to appreciate the impossibility of the binds in which people found themselves.

Hämäläinen turns the “agency” dial as far as it can plausibly go, and then gives it another twist. This has benefits. You cannot read Indigenous Continent and retain the belief that Native societies quickly and permanently collapsed. Hämäläinen’s book not only exposes settler boasts of continental conquest as self-serving fictions; it rejects the entire settler sense of what constitutes American history. It is stand-everything-on-its-head history, offering the thrills of a sharp perspectival flip.

Yet it is also caricatured history. Small groups appear big, and the gargantuan United States appears implausibly small. Native Americans are shown to be so superhumanly capable that the causes and consequences of settler colonialism fade from view. So does the tragic dimension of American history: the understanding that sometimes historical forces outmatch our abilities. Indigenous Continent is full of fearsome Native warriors and agile Native politicians. What it’s missing is the creativity, irony, and inner turmoil of people facing an onslaught that, for all their resilience, was beyond their control.