Photograph of Sarah Smarsh. All photographs from Kansas by Ilana Panich-Linsman, September 2022, for Harper’s Magazine © The artist

In January 2019, when I found myself sitting across from Mindy Myers in a cramped D.C. coffee shop, the new resistance was riding high. A diverse lot of Democrats had just taken control of the House of Representatives, positioning themselves to curtail Donald Trump’s devastating abuse of the presidency. Trump’s chances of reelection looked questionable amid perpetual scandal and calls for impeachment, and even the Senate now seemed within reach.

Myers had just finished her tenure as the first female executive director of the Democratic Senatorial Campaign Committee (DSCC). Before that, she’d enjoyed a perfect record managing three Senate races, including Elizabeth Warren’s 2012 campaign, and she’d served as Warren’s chief of staff during her first term.

That afternoon, we were discussing electoral prospects in Kansas, which national Democrats generally consign to the “red state” pile with little if any thought. I had just come from the nearby PBS studio where I had recorded a segment on the dangers of using pat binaries—urban and rural, red and blue, coastal and middle—to predict the politics of entire groups, states, or regions. Such crude frameworks render invisible millions of Americans, I’d argued, and often become self-fulfilling prophesies when used to determine the distribution of political resources. So it was heartening to hear one of the eminent political strategists of our time agree that Democrats had a reasonable chance of winning a Senate seat in my home state for the first time since 1932.

Some 30 percent of registered Kansas voters are unaffiliated, and the state defies easy categorization. In the decades after its consequential entrance into the union as a free state in 1861, Kansas led the nation in movements such as women’s suffrage and Eugene Debs–era socialism. In more recent years it has produced such far-right forces as the Koch brothers and the former governor Sam Brownback. Kansas has sent a lot of Republicans to Washington, but it is also the only state in the nation to have elected three Democratic women as governor.

From my uncommon vantage among national journalists—as a Kansas resident raised by poor wheat farmers with little formal education—I knew that the results of red-state elections often say more about our electoral system than about the character of a place. While a plurality of Kansas voters are Republican, the MAGA-hat-wearing white voters of media fascination are a statistical minority with outsized influence. As I saw it, that minority had seized control via targeted disinformation, voter suppression, gerrymandering, and dark money while the national Democratic Party conceded indefinitely.

Myers and I were talking about changing all that. The longtime Kansas senator Pat Roberts had just announced that he would not seek another term. Assessing potential candidates, the Cook Political Report had moved the race from “likely” to “lean” Republican.

Roberts had held his Senate seat since the conservative takeover of Congress in 1996, and he’d played a crucial role in the Republican Party’s rightward shift. During his final term, he voted in line with Trump’s wishes 94 percent of the time. But back home, his name had begun to fade. In 2014, his claimed Kansas residence—on a country club golf course—was revealed to be owned by campaign donors. That year, an independent candidate trimmed seven points from Roberts’s previous victory margin.

By that time, I had already observed among working-class Kansans a progressive parallel to the more widely discussed right-wing anger toward “elites.” Pundits in New York routinely conflate populism with conservatism, but populism is not an ideology directed left or right; it’s a rage pointed upward, toward those in power. Over the years, this rage has fueled liberal as well as conservative impulses. Populism built the labor movement, the New Deal foundation on which the modern Democratic Party stands. During the 2016 primaries, more Kansas voters—including my own white working-class family—caucused for Bernie Sanders than for Trump. Though long written off by top Democrats as a waste of campaign resources, the state was ripe for political realignment—if only the right candidates would show up and talk to people.

This was the argument I’d been making in my own writing and in public interviews for years. But in that D.C. coffee shop, I wasn’t just commenting on how to reach blue-collar communities and flip a seat. I was considering trying to flip it myself.

Like many working-class Kansans, I was raised with an aversion to both major parties. “They’re all crooks,” my family would say, an expression of deserved distrust—but also a defense mechanism, I think, for those lacking the time and resources required for civic engagement.

Nonetheless, I demonstrated uncool activist tendencies at the tail end of Generation X. During my Nineties adolescence, downtrodden skater types asked me, a sullen cheerleader who haunted the art department, to speak on their behalf at student protests against the preferential treatment of male athletes. As editor of the school paper, I rankled the administration by invoking Kansas’s constitutional expansion of press freedom for high school journalists. In the same spirit, I joined student government and was even elected speaker during an annual model legislature at the statehouse in Topeka. Wielding the gavel, I relished frowning at bills brought by students from monied Kansas City suburbs to beautify their already lovely neighborhoods.

I came of age at an inspiring moment for girls who sought to change the world. I turned twelve in 1992, the “Year of the Woman,” during which a record forty-seven women were elected to the House of Representatives, twenty-four newbies among them. That same year, women gained four Senate seats, joining two incumbents for a (sadly) historic 6 percent of the upper chamber. One of those incumbents was Nancy Kassebaum, a pro-choice Kansas Republican who served in the Senate from 1978 to 1997. During Kassebaum’s time in office, the Democrat Joan Finney served as the state’s first female governor.

It was a good time to be a girl, yes, but I was a poor one. What threatened my potential was not just my gender but my double shift waiting tables the night before an exam. If I had been at a New England prep school rather than a public school surrounded by row crops, I might have taken the advice of teachers who half-joked that I would “make a great lawyer, with the way you argue” and set out for a career in lawmaking. Instead, I eyed local journalism, which had long been a relatively accessible—if largely white and male—vocation for scrappy talent from low places.

As a first-generation college student fresh off the farm, I experienced not only economic hardship but the brutality of American classism. I reported a story for my college paper about low-income students falling through the gaps of class-biased questions on the Free Application for Federal Student Aid. The Associated Press picked it up and distributed it nationally. This would become a pattern throughout my career: middle-class reporters were blind to stories that I was born to see.

During my senior year of college, I received a research grant from a federally funded program for first-generation, low-income, and minority college students. With it, I began work on a book about the vicious ways our country’s class structure affected my family and millions like it. In the coming years, I would write many of its passages between jobs while I had neither health insurance nor sufficient food.

I was an unlikely critic of the American up-by-your-bootstraps narrative. I had left home in 1998 as a “fiscal conservative” and cast my first vote, in the 2000 presidential election, for George W. Bush. Away from my small town and Catholic church, though, my information sources changed dramatically; so did my ideas. Soon after my college graduation, the revelation of lies about weapons of mass destruction in Iraq turned me completely against the Republican Party, with which I had already disagreed on a host of social issues.

Having awoken to oligarchy while working on my book as a graduate student at Columbia, I cast my ballot in 2004 for Ralph Nader. I remained vexed by corporate influence over both parties and did not register as a Democrat until my late twenties, in order to caucus for Barack Obama in 2008.

By then, I had finished a draft of my book, which I had begun showing to agents and editors. For a decade, New York publishing professionals told me they liked my voice but weren’t sure why my family’s story would matter to readers. Then a handful of my essays on class went viral, and in the spring of 2015 my book was sold at auction. The manuscript grew into a researched cultural critique and intersectional social analysis, blending policy and history with generational stories from twentieth-century rural Kansas. Published in 2018, Heartland: A Memoir of Working Hard and Being Broke in the Richest Country on Earth became a bestseller and a National Book Award finalist. Liberal and conservative, black and white, indigenous and immigrant alike waited in book-signing lines to convey their own experiences of class and place.

When Roberts announced his retirement a few months later, followers of my work surprised me by posting calls of “Smarsh for Senate” on social media. Young activists began to chant “run, Sarah, run” at my lectures.

I had started receiving requests to speak at campaign events, all of which I declined so as to avoid a conflict of interest. Two days before my meeting with Myers, though, I had served as master of ceremonies at the inauguration of Kansas governor Laura Kelly—a Democrat whose victory had been part of the midterm-election “blue wave” and whose invitation, I reasoned, was in service to my state rather than partisan activity. Inside the state capitol that afternoon, the newly elected Democratic representative Sharice Davids took a selfie with me. I had recently written a New York Times opinion piece about the meaning of Kelly’s and Davids’s wins for the rest of the country. Speaking with Myers now, I was poised to become part of that meaning.

Myers likened my evolution to Warren’s transformation from young Oklahoma Republican to bank-busting legal scholar to progressive political leader. “People asked Senator Warren to run because of the work she had been doing for years outside of politics,” Myers said. “It’s more common that someone wants to run, and then they try to figure out what they stand for—what’s my message? For you it’s the other way around.”

The message was my life’s work; the rumbling political fault line of our century, the “rural-urban divide,” was the defining chasm of my life. I was not just an analyst but an embodiment of the prairie populism that would be essential, it seemed to me, to flip a Kansas Senate seat.

But as a general rule, I prefer that people in the upper echelon of government have experience, you know, governing. If seeking office had been my idea, I wouldn’t have thought to start with the Senate. Considering such an audacious move, I heard in the back of my head a criticism that had stung the ambitious working-class girl in me more than once: Who does she think she is?

When I voiced this concern to Myers, she smiled. “You’re asking very different questions than the last person I talked with about this race,” she told me. “Women ask whether they’re qualified. Men ask how much money they can raise.”

Myers had already referenced money at the start of our meeting, saying that I might receive the full support of the DSCC. The viability of my candidacy, she explained, depended less on common political wisdom than on the rare thing that I am: a progressive woman from working-class, rural America with an established body of work on economic inequality.

“Because of your story,” she said, “your campaign could get the sort of national attention that Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez or Beto O’Rourke got during the midterms. Your national fundraising potential could be—I hesitate to say it, but—limitless.”

Recent elections have seen an unprecedented number of onetime outsiders enter the wealthy, white, male island of privilege that is Washington. These include Davids, a Native American lesbian raised by a single mother who served in the U.S. Army, and Ocasio-Cortez, a Puerto Rican American still in her twenties when elected to her New York House seat.

Many of these candidates have been recruited and trained by new and old organizations committed to diversifying the government. These range from Emily’s List, which has raised close to half a billion dollars over four decades to boost pro-choice female candidates, to Run For Something, which was founded on the day of Trump’s inauguration and, at its two-year mark, reported that it had connected with thirty thousand young, progressive would-be candidates for local races. Thanks in part to these efforts, the 117th Congress is the most racially and ethnically diverse in U.S. history, while also containing a record number of female representatives. Recent years have seen representational gains for the LGBTQ community and disabled people, as well.

But one area of acute underrepresentation remains underdiscussed, if not ignored: socioeconomic class. According to a study by the political scientists Andrew Eggers and Marko Klašnja, the median individual wealth of Congress members has since the Eighties consistently been in the ninety-fifth percentile of U.S. households. The same study estimated that two-thirds of Congress members were millionaires.

As outlined in Nicholas Carnes’s 2018 book, The Cash Ceiling, more than half of U.S. citizens work in manual, service, or clerical labor, yet the average congressperson has next to no work experience in these industries. Fewer than 40 percent of Americans aged twenty-five and older have a bachelor’s degree, while 100 percent of current senators and 94 percent of representatives do. This is a notable shift from sixty years ago, when about a quarter of each chamber’s members didn’t have college degrees.

What are the implications of a government whose members have fuller bank accounts, softer hands, and more academic credentials than the average American? For one, Eggers and Klašnja found that greater wealth among congress members correlates with more conservative voting records on economic policy around tax rates, finance, welfare, and trade. This holds true for both major parties. As working-class and poor Americans suspect, rich folks of all political stripes generally protect their own.

Hateful dismissals of those with low incomes, dirty jobs, or “uneducated” backgrounds leave us unable to recognize that such people not only are capable of governing but possess insights necessary for fixing systemic woes from which they have suffered—woes that our credentialed leaders often have a vested interest in failing to solve. I was raised by intelligent people whose creative problem-solving, honed not by textbook theories but by lifelong fights to survive, might have made them fine policymakers.

Carnes and his fellow political scientist Noam Lupu assessed the efficacy and educational levels of political officials between 1875 and 2004 in more than two hundred countries. They found that college educations did not denote more successful leadership. Indeed, while the American working-class voter has shifted right in recent years, our present democratic disaster was plotted and enacted by prosperous white people with Ivy League degrees.

Grassroots movements, such as Black Lives Matter, the Poor People’s Campaign, the Sunrise Movement, and Native American efforts to amplify the crisis of missing and murdered indigenous women, have disrupted class paradigms in activism. But for those without an ample financial cushion, entering politics—especially to seek high office—continues to entail a potentially ruinous level of sacrifice and risk.

Ocasio-Cortez has written on social media about the particular challenges for working-class people elected to office, such as paying out of pocket for residences at home and in Washington, and has spoken about the economic turmoil her family suffered after her father’s early death. While Ocasio-Cortez’s aspirational parents and Boston University education afforded her glimpses of the middle class, her work in Washington provides regular reminders of her origin.

The mere notion of my candidacy marked a shift in the post-Trump political landscape. I was a youngish female journalist who grew up in single-wide trailers and farmhouses, tending fields and slopping hogs. The seat in question was occupied by a well-to-do, eighty-two-year-old white man first elected to the House in 1980, the year I was born.

After Heartland was published, I looked up from two decades of hustle and realized that I had attained all that I had sought: a safe home, a savings account, creative fulfillment. A powerful producer wanted to make Heartland into a television series. I’d been named a fellow at the Harvard Kennedy School. I had stopped collecting coupons and started buying organic. I had a pile of student debt and a house with a caving roof, but I felt satisfied, secure, content—and so very tired.

At the same time, I was being asked to set aside my writing and begin at the bottom of yet another mountain. My instinct was to guard the career I had fought to build. Once I had crossed the threshold from the Fourth Estate to the government it monitors, it seemed to me there would be no going back.

Granted, my own state provided plenty of precedent for ink-stained newspapermen moving into politics. My journalism school’s namesake, William Allen White, was a small-town Kansas editor and publisher who became a national voice in the Progressive movement and ran for governor in the Twenties; during the same period, the Wichita newspaper editor Henry J. Allen held the governorship and, briefly, a U.S. Senate seat. My own hesitation had perhaps less to do with broad journalistic ethics than with my unusual position as a critic of both parties. While cognizant of the problems with feigned objectivity, I am also wary of the untroubled sliding between paid work for news networks and political campaigns so rampant in today’s opinion-dominated media. I value being unbeholden to any organization or agenda over the security such affiliation provides, and I have lived my entire professional life accordingly.

What of personal policies, though, when authoritarianism is on the rise? The stakes of my decision were heightened by the increasing presence of far-right ideologues at all levels of government. Federal elections in Kansas have never brimmed with viable Democratic candidates; in local and even state races, Republicans often run uncontested.

For years, I had occasionally harbored thoughts of one day seeking office. My eventual prompt had come from without, though, not from within, and thus said more about my country than it did about me; this was an encouraging sign for our embattled democracy, I thought—that someone from my broke-ass ranks would be nudged toward holding such a position.

I had covered government as a reporter, but I could only make educated guesses about what it would mean to enter the fray. My initial thought was to run as an independent, maybe even to promise that I’d only serve one term if elected. But I knew enough to recognize these impulses as self-defeating, given my lack of personal wealth and need for party support.

So I set out, as one does in politics, to “explore” the options in our two-party system. As I would learn, my exploration differed from that of many in that I didn’t conduct polls to gauge electability or hold meetings to secure endorsements. Most people who explore campaigns are already, in effect, campaigning. For me, the project was to discern whether I wanted to run, and if so, how I would go about it.

While speaking about rural issues on Capitol Hill, I had met the staff director of the Senate Democratic Steering and Outreach Committee, Laura Schiller. She pointed out that a journalistic platform allowed me to effect change without the constraints of political life.

“Do you really want to do this?” she asked in a gentle but warning tone.

Her subtle discouragement felt disappointing, which in turn signaled that something in me wanted the Senate seat.

Schiller connected me with Myers. After our coffee date, my questions multiplied, but I found more people ready to help answer them. Perhaps my most pressing concerns were financial: I didn’t have the luxury of spending a year on the stump with no income. I had paid lectures on university campuses and at professional conferences booked well into 2020. If event organizers didn’t cancel my contracts when I announced—which some might do to avoid angering taxpayers and donors—could I keep those dates?

Yates Baroody, a regional director for Emily’s List, assured me that I could. Describing the ecosystem of organizations that might back my campaign, Baroody observed a paradox: the very thing that made me a good candidate—my direct experience of socioeconomic disadvantage—would be my greatest barrier in a race in which many candidates are millionaires at the starting line. Emily’s List could potentially help by funding campaign staff, assisting with messaging and press, and connecting me to other organizations.

Baroody suggested that I wait to see how the field shook out. She urged me to “start lean.” Maybe launch an exploratory campaign, which had a different set of reporting rules from a formal candidacy. Hire a fee-based consulting firm. I looked at my house’s damaged ceiling, the repairing of which would be done by my construction-worker partner when he found the time. A “fee-based consulting firm” sounded like something on a shiny planet where I had landed in a jalopy space rocket missing a muffler.

Rurality and poverty are formative yet often invisible aspects of identity, and I was relieved to discover fellow hayseeds and class-straddlers as I continued my conversations. PaaWee Rivera, who worked on Warren’s 2020 presidential campaign, shared during a phone call that he had grown up in rural New Mexico, a Pueblo of Pojoaque tribal member. He was happy to see a rural advocate considering a run. Warren’s campaign manager, Roger Lau, the son of Chinese immigrants, had been working in a cardboard factory when he landed an internship in John Kerry’s Senate office.

Lau expressed frank precautions: The financial issue was real. He’d seen candidates spend their retirement savings and go into debt. The campaign would exhaust me. A presidential-election year like 2020 might hurt a Democrat’s chances in Republican-leaning Kansas, since more people would show up at the polls. But Myers was excited about my potential, Lau told me, and he was, too.

“You and Senator Warren have a lot in common,” Lau said. “You didn’t plan on this. You didn’t seek it. You have a mission you can articulate because of your origins.”

He urged me to get as many commitments as I could before the start of the campaign. “Donations, endorsements, help on the trail. Get as much as you can. And know that not everyone will make good on their promises.”

“Sarah? It’s Elizabeth.”

During the 2020 election, Warren’s phone calls to shocked small donors would go viral. Her calls to Democratic candidates, or potential candidates, up and down the ballot produced fewer memes but were no less significant.

During the 2018 midterms, Warren raised or donated $11 million to and for other candidates, including about a hundred women. But when she dialed my cell that February, four days after announcing her candidacy for president, I was still so ignorant of campaign finance laws that I had no idea candidates with big war chests could disburse that money to other campaigns. A phone call that I might have approached as an audition was instead an earnest conversation.

I was in a hotel room in Hattiesburg the morning after giving a lecture at the University of Southern Mississippi. Before our appointed time, I’d made a list of things to ask or mention. I’d pulled the hotel phone cable out of the jack and double-checked that I had hung the privacy sign on the door. This felt like the most consequential call of my life. As a citizen and a voter, I believed in Warren. If she believed in me, what choice would remain?

I heard sloshing and clanking. Warren was at home, washing dishes. I refused to call her “Elizabeth.” She told me she had read some of my work and felt a kinship.

I asked how she felt about her life since entering politics, and she described her day-to-day.

She admitted that she was at a different phase of life when she “got in,” and suggested that I speak with someone closer to my age, too.

“Sometimes the fight comes to your door,” she pointed out. “And we don’t get to decide what year it is or whether it’s a Tuesday.”

With those words, I felt burning within me the hellfire of forty million Americans living in poverty. I had been agonizing over whether this was the right choice for me, and Warren was talking about us.

“So how do you know when to announce?” I asked.

“When you have the right team,” she said. “The right people come before all else. You want people who are good at the things you’re not good at.” She said she could connect me with such people.

I told Warren about my family’s struggles and about the thousands of messages I had received from people of different races and creeds desperate to share their stories.

“I can hear that you’re in this for the right reasons,” she said.

We had been on the phone for half an hour, but she was not pulling away. She left a silence for whatever else I needed to say or ask. I couldn’t bear that someone so decent was giving so much when she could surely use ten minutes of quiet. I thanked her, signaling goodbye.

“Let’s stay in touch,” she said.

As I hung up, I was all but certain that I would run.

First, I would need to get my footing in this new public life: pay some bills, restore my health amid a long and taxing book tour. I kicked around the idea of waiting for 2022 to challenge the junior—soon to be senior—senator, Jerry Moran.

Moran is a less offensive brand of Republican than Roberts. His votes occasionally defied Trump’s wishes and, unlike four of Kansas’s six congresspeople, he would later vote to certify Joe Biden’s victory. His co-sponsoring of the bipartisan PACT Act, assisting veterans who suffer from toxic exposure, was vital to its passing this year. Nonetheless, he aligns himself with a party I find vile and destructive.

Excited to hear that I was leaning toward going for it, Myers helped me think through the arguments for and against 2020 and 2022. Unseating a popular incumbent is presumed more difficult than pursuing an open seat, and the iron was hot for untraditional Democratic candidates like myself. But a Democrat running in a majority Republican state could also benefit from lower midterm voter turnout. The 2020 presidential outcome would affect 2022 down-ballot races in unforeseen ways. And there was speculation that secretary of state Mike Pompeo, a former congressman from my district, would enter the 2020 race; analysts deemed him a shoo-in for the Republican nomination.

Pacing my home office in Kansas, I realized that such calculations meant little to me. If I were someone who made decisions based on probabilities, who took risks only when the odds were in my favor, I might still be waiting tables at a Pizza Hut on a windswept highway.

For the first time, Myers said explicitly that she would be honored to be part of my campaign—an enormous boon not just because of her prominence but because she was, I thought, a humane person trying to do good in a system whose rotten parts she knew well. No one else had clearly stated such a commitment, and her vote of confidence moved me. With one major piece in place, I began to envision how my campaign might look.

I could only do it, I decided, if I did it the way I had done everything else in my life: more concerned about the means than the end. We would value open-heartedness over assumptions—over data, even—by knocking on doors where one isn’t supposed to bother. We would value life experience over “expert” analysis by putting “uneducated” people in leadership roles. We would resist burnout culture by refusing to run ourselves into the ground. We would be told we were naïve and doing it wrong. But how had doing it right been working out for Democrats seeking a Senate seat in Kansas for the past ninety years?

I discussed some of these matters with Davids soon after she was sworn in. Born just two months before me, Davids was better suited than anyone to reflect on campaigning and going to Washington from our state in our season of life.

A member of the Ho-Chunk Nation, Davids was, alongside New Mexico’s Deb Haaland, one of the first two Native American women elected to Congress. She was also the first openly gay Native American elected and the first openly lesbian person elected from Kansas. Intersecting with these marginalized identities is Davids’s less discussed working-class background, which she described to me as her greatest barrier to entering politics.

By law, candidates are permitted to take a salary from campaign funds, but the practice remains frowned upon, an attitude that clearly favors those of independent means. Davids instead worked ten hours a week as a tribal consultant while on the trail, giving up most of her legal work and with it most of her income. To compensate for the loss, she moved in with her mother. She also deferred her student loans, spent her entire retirement savings, maxed out her credit cards, lived without health insurance for more than a year, and forbade herself from buying moisturizer or a new pair of shoes.

While I worried about money, I told Davids, I was more concerned about my health. As a former triathlete who takes up DIY construction projects for fun, I was startled to find myself so run-down by the book tour. The requests to write, speak, comment, help a cause, or hear a story had not slowed. I had missed Thanksgiving while laid flat by a virus, and I underwent a minor surgery a month later. My blood work revealed severe deficiencies. If I didn’t decrease the stress in my life, my doctor cautioned, I might face more serious problems down the road. My body didn’t need a Senate race; it needed a cabin in the woods.

I had worked demeaning, back-busting, soul-crushing jobs for inadequate pay—the same jobs being worked by millions of people at this minute—and so hesitated to mention the difficulties that came with my new position of privilege. But as a member of a family prone to desperate situations, I had learned the hard way that there is no caring for others without first caring for yourself. I asked Davids—a former professional mixed martial arts fighter known to do push-ups at the Capitol—how she managed.

“We don’t talk enough about the emotional and physical wear of it,” she said.

She underscored the importance of delegating tasks and trusting the people around you to do their jobs. She also had a support system outside of politics, which she called her grounding force.

She was guided, she told me, by a question posed by Brené Brown in her best-selling book Daring Greatly: “What’s worth doing even if I fail?”

“Even if I had lost,” she said, “I think it would have been worth it. I would’ve done it the same way.”

By March, buzz about my potential candidacy was growing.

I had been ignoring a message on Twitter from a former federal attorney, Barry Grissom, a Democrat planning to run for Roberts’s seat. When I finally called the number he’d provided, Grissom—an Obama appointee living in a tony suburb of Kansas City—was surprised to learn that I lived in Wichita, more than a rung below his area in economic and political capital. He let me know that he would be announcing his candidacy, and he helpfully suggested that I run for the House in 2022. I told him that his plans had no bearing on my decision. He invited me to dinner with him and his wife sometime. I wished him the best.

Later that month, as the cherry blossoms bloomed, I flew to Washington to meet with the Senate minority leader Chuck Schumer and the Nevada senator Catherine Cortez Masto, who was serving as chair of the DSCC, which raises and distributes about $300 million to boost its preferred candidates in election years.

Before our meeting, I went for a run along the National Mall. I petered out by the time I reached the reflecting pool, its concrete and right angles so unlike the catfish pond where I used to sit and think.

It happened to be my mother’s birthday. She had died of breast cancer four years prior at the age of fifty-three. I had permanently moved out of her apartment and into my grandparents’ farmhouse when I was eleven years old. Still, we had developed a profound friendship later in life. In her last days, I had been one of her primary caregivers, and I’d held her hand when she passed. I thought of her hard early life: abusive stepfathers, destabilizing poverty and transience, accidentally conceiving me with a farm boy in a basement on the Kansas prairie when she was seventeen. I wondered what she would think of all this.

Brilliant and well-read, my mother was unimpressed by celebrity and carried herself with regal self-assurance despite society’s relentless attempts to shame young mothers living in poverty. Throughout my tumultuous childhood of verbal abuse and emotional neglect, much of it perpetuated by her traumatized young self, she still somehow conveyed the idea that I was exceptional and destined for greatness. I could hear her saying, with a shrug and an exhale of Marlboro Light smoke, that my being in Washington to discuss a Senate run was the least surprising thing she’d ever heard.

I made my way past a high school band performing on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial, and I remembered climbing those steps at their age after qualifying for a national communications contest. Now, as I stood in my running tights at Lincoln’s marble feet, a male tourist asked me to take his photo. After I returned his camera, he said that maybe we could hang out later. I walked away.

As I attempted to read the inscribed Gettysburg Address and contemplate the meaning of our republic, the man followed and lurked. I was weighing an attempt to become the second woman elected to the Senate from Kansas in its hundred-and-sixty-year history. Being sexually harassed at the Lincoln Memorial seemed about right.

At the congested DSCC building, the senior adviser Christie Roberts waited with me for an office to clear. Roberts had managed Jon Tester’s successful 2018 reelection campaign, and I told her that the Montana senator had co-hosted a conversation about Heartland at a summit on rural issues the previous fall. When commenting on the manual labor described in my book, Tester raised his left hand, three fingers of which had been lost to a meat grinder.

Senator Kyrsten Sinema of Arizona emerged with someone who apologized for taking more than their allotted time. Schumer arrived, ushered another person into the office, and gave us a “just a minute” gesture. It was 6 pm. One thing my current profession had in common with government work was that evenings, weekends, and holidays were irrelevant.

“Do you mind if I take my shoes off?” Schumer asked as Roberts and I sat down. I didn’t mind, of course, but they were already off. He stretched his feet across the top of the desk and leaned back as though it had been a long day. He looked over a few notes someone had prepared and started grilling me: Where was I from? Why was I here now? If a small business owner said he couldn’t afford to pay his employee’s health insurance premiums, what would I tell him? What did I think about the Green New Deal? How would I rank these five adjectives, beginning with the one that described me best?

I lobbed back answers. He turned to my career.

“How many books have you sold?”

No one had ever asked me that, and I didn’t have an answer.

“I don’t know,” I said, honestly. “I asked my publisher not to tell me.”

Schumer looked as though he didn’t believe me.

“Okay, okay,” he said. “Was it a bestseller? And I mean a New York Times bestseller.”

“Yes,” I replied.

“Ah, she’s modest,” he said. “How many weeks?”

“Just one.”

“So just a ballpark: You haven’t sold a million copies or anything like that.”

“No.”

Aiming to explain what had brought me here, I told him that my journalism had addressed working-class issues years before doing so was in vogue. He replied that he, too, had long been talking about these issues, as evidenced by his 2007 book, Positively American: Winning Back the Middle-Class Majority One Family at a Time, whose low sales he lamented.

That the leading Senate Democrat would so casually gloss over the vast difference between the working poor and the middle class so beloved by speechwriters dismayed me.

“You do a lot of public speaking,” he said, looking over the printouts in his hand.

“Are you going to ask how much I get paid for a speech?”

I had taken a tone, and Schumer raised his brow.

“I’m asking you these things to gauge your prominence, your clout,” he said. “You get out there and people will come at you, and it doesn’t matter how good you look.”

I drew a breath and steered the conversation to Schumer’s own journey into politics. He lit up at my questions and paused to look at Roberts.

“Now see, you don’t even know this because you never ask me questions like this.”

We went on to discuss the climate in Kansas. Schumer brought up “that fucking Trump.” At this, he gazed into the distance with true loathing—the first moment that confirmed we were on the same side.

As he gave his assessment of various Kansas Republicans, including Moran (an alright guy on the wrong team) and former secretary of state Kris Kobach, who would go on to run for the Senate seat (even worse than Trump), it struck me that Schumer was a good judge of character.

He turned back to numbers. Had I done any polls? I should go on a trip across the state and gather that sort of data, he said.

I thanked him for his time and moved toward the door.

“Wait,” Schumer said.

I stopped.

“What’s your middle name?”

I smiled. “Jean.”

“Sarah Jean!” he exclaimed, delighted. “That is what we’ll call you from now on. It doesn’t get any more down-home than that.”

On the plane back to Kansas, I listened to the last voicemail my mother had left me. Her body was so weak by that time that she strained to speak above a whisper. I turned my face toward the window and cried quietly.

The combination of her birthday and a stressful trip dislodged something deep. I had just ended talks with the television network because the offer didn’t feel right. I was relieved to be flying away from the annals of global power. What the hell was wrong with me?

I thought about my last brush with government work, in my twenties, when I’d struggled to pay the bills while doing freelance reporting for national publications from a region where newspapers were collapsing. The state secretary of corrections had recommended me for a communications job at one of the most visible state agencies in Governor Kathleen Sebelius’s administration. The position came with a higher salary and better benefits than I had ever received, and I knew that former colleagues were taking jobs in public relations. I interviewed with enthusiasm and received an offer. But when I thought about why I had become a journalist—to hold government accountable—it felt wrong to write its press releases, even if I happened to agree with them. Instead, I took a position at a non-profit that came with less money and less prestige.

After I declined the state job, I heard that I had offended more than one person in Topeka. Did I know how many people would love to have that position? Who did I think I was? I recall mailing apologetic thank-you notes.

I thought too of the time that I resigned from a tenured professorship at a small university, a seemingly crazy act for someone with no assets to fall back on. Prompted by a perfect storm of my mom’s terminal illness and my employer’s savage institutional sexism, the decision had shocked many but also made way for my writing dreams to come true.

One person who had asked no questions and uttered no doubts in either case was my mother, a woman who put little stock in financial stability or job security because she had lived without both—a difficult condition that contained the magnificent freedom of answering to no one.

When I arrived home from Washington, I told my partner that my mind was made up. I wasn’t running.

Well, 99 percent of my mind was made up. The other one percent was a real bitch.

Like a test from the universe, a voicemail soon arrived from a Kansas City Star reporter, whose online messages I had ignored. More than three months since speculation had begun, I felt I should say something, if only to communicate the care I had put into the decision. In the interest of control, I replied by email with a careful and brief recounting: I was honored to be summoned, I was determining how best to be of service to the marginalized groups I championed in my writing, and yes, I had visited the DSCC.

Eighty-three minutes later, the Star published a headline on its website: kansas author sarah smarsh met with schumer about possible u.s. senate run in 2020. The article claimed that a midterms analysis I had written in November for the New York Times hinted at designs on public office—designs I didn’t even have at the time. Annoyed and amused, I pointed out on social media that my Times piece, which had suggested that centrist Democratic women such as Kelly and Davids might demonstrate how Democrats could reclaim red states, was actually an argument against nominating thoroughly progressive me.

That misleading reference had been removed by the time the story reached my doorstep the next morning in the print edition of the Wichita Eagle, a sister paper of the Star. The front page featured my photo and a teaser: smarsh eyes senate run.

I received an excited text from an old friend who had been a young associate producer for NBC News at 30 Rockefeller Plaza while I was an investigative reporting intern at the network’s New York City affiliate a few floors away. She sent me celebratory emojis and suggested coming to Kansas to make a documentary about my campaign.

Over the previous few months, many others who’d seen my name in pre-election chatter had offered to donate their time and skills. This had inspired in me a sense of loyalty and responsibility. In the coming weeks, at lectures across the country, audience members reliably asked whether I was running, told me I should run, and promised they would contribute if I did. What to say, when I didn’t want to encourage speculation but wasn’t ready to close the door? I said thank you.

At a town hall on rural health in Hutchinson, not far from the farm where I grew up, a local reporter put a recorder in my face when I walked through the door and was clearly put out when I smiled and said I wouldn’t comment on the election. She later filed an open records request to determine how much I had been paid for the appearance. I was a private citizen who had booked the talk for a fraction of my usual rate in order to assist a non-profit effort, but the reporter wrote a story soliciting outrage.

Event organizers whom the reporter had contacted warned me about what was coming. I rushed to make sure my home address was not included in any of the acquired documents or emails, a precaution that is unfortunately necessary for women in the public eye. My experience was but the tiniest taste of the invasive scrutiny that female leaders endure.

As I wrestled with my diminished but persistent itch to run, I was aware of my vulnerability in a game where most players have thick, expensive walls built between themselves and the world. I was a small woman who was frequently sexualized. I had encountered my first stalker at age fourteen. (He had turned up again, twenty-four years later, at a Heartland launch event.) I did not reside in a gated community or a doorman building. I lived down the road from my family in a working-poor neighborhood of cracked sidewalks and condemned houses. My old house had settled in the Kansas silt such that the locks on the windows didn’t latch, a defect that hadn’t fazed me when I moved in; after growing up in the country with unlocked doors, I thought wedging lengths of two-by-four into the window jams worked just fine. While the danger faced by candidates and public servants would not keep me from doing a job I felt meant to do, my exposed life made the decision that much heavier.

I had been sitting with my potential candidacy since early winter, and now spring was moving toward summer. For months, I’d juggled other professional and personal choices with the possibility that I’d soon be on the campaign trail. Assembling a solid team would require time. I needed to make up my mind.

By June, not long after the Kansas City Star headline, I thought I’d finally determined that politics was not the right use of my strengths. Then James Thompson announced that he had Stage IV cancer.

An Army veteran who had been homeless in his youth, Thompson had altered the political map in Wichita and surrounding areas. Vying in a 2017 special election for the seat vacated when Pompeo joined the Trump Administration, Thompson had run as a progressive Democrat against the conservative Republican Ron Estes in the red fourth district—home to the Koch family. Despite a grassroots campaign that attracted national attention, Thompson received no support from the Democratic Congressional Campaign Committee. During the homestretch of the race, the Kansas Democratic Party declined to pay for a $20,000 mailer while prioritizing other races. Thompson lost by seven points, knocking an incredible twenty-four points off the previous election’s Republican victory margin and suggesting that additional party funds may well have altered the outcome.

After interviewing him several times, I had come to know Thompson personally, and I had a deep respect for the civil-rights attorney and former bouncer. Thompson ran for the same seat in 2018, losing by a much wider margin, and he told me that his finances had been gutted by two years of campaigning while paying off a mortgage and student debt. He was insured through tax credits in the Affordable Care Act. In effect, Thompson found his cancer treatment options limited by his run for Congress as an anti-corporate fighter for economic justice. He joked on social media that he might finally win an election, since he came with mortality-imposed term limits.

I was devastated for Thompson and enraged at the Democratic Party. In a flash, I resolved to go fight for the goddamn Senate seat. If I ran and won, I told myself, I would add one more vote for structural changes benefiting people in poverty, workers, children, the environment, and public education. Left-leaning candidates in other red-state races might receive more support. If I ran and lost, at least I would have amplified the plight of the poor and marginalized throughout the campaign, possibly elevating class consciousness and inspiring future working-class candidates of all genders and races.

I reached out to Thompson. Over the course of several weeks, he gave me advice and offered to share the impressive data his two campaigns had worked hard to amass. I renewed conversations with Emily’s List and with Myers, who would go on to guide Kamala Harris on her path to the vice presidency. I also had discussions with Justice Democrats, Brand New Congress, and Sebelius; these amounted to questions from me rather than encouragement from them, but most doors seemed open enough. I reached out to Kelly, who invited me to the governor’s residence in Topeka. I received solid advice from then-presidential candidate Marianne Williamson. I exchanged more texts with Lau.

A rumor emerged that I might run for the House instead, which I never once entertained. I suspected the misdirection had been sown by another Democratic Senate campaign.

“They’re scared,” Thompson told me. “You are their biggest threat.”

It felt, yet again, like everything was falling into place for my candidacy. As Warren had predicted, the fight had shown up at my door, and the knock was not gentle. To refuse to answer felt selfish, careless, a waste of potential influence for a girl born to people who were never given such a chance.

When I was that girl, though, with wheat spikelets caught in my secondhand socks, I already understood what I had to offer the world.

While people I knew lost eyeballs and limbs laboring on farms and in factories, I learned to value the work of my body. I was constantly moving—tending, mowing, clearing, hauling, feeding, cleaning—to avoid being chided for the worst offense in my community: “sitting on your ass.” The chiding was born of necessity; there was much to do and no hired help to do it. It was also, though, class maintenance—my elders ensuring that I understood society’s plans for me so that I would fall in line, make a paycheck, and survive.

I did that labor and will be forever grateful for it, but I knew it wasn’t the life I was meant for. The books I cherished and the voice inside me demanded a writerly direction that no one applauded. Why would they? In our society, journalism is so devalued as to be expected free of charge, and creative work is worth less than just about any other kind.

I long ago climbed over those socioeconomic hurdles and that societal bias to pursue my career. Late in my consideration of the Senate race, though, I realized that my recurring urge to run stemmed in part from an unconscious belief that politics is a more effective means for social change than what I already do. And, perhaps, more worthy of the respect for which a poor farm girl once longed.

The pen is not more powerful than the AR-15, carbon emissions, unsustainable consumption, xenophobia, unlivable wages, nationalism, the prison industrial complex, the military industrial complex, the medical industrial complex, or dark money’s political influence. It is, however, antecedent to some future world that will not abide these things. Of all the reasons that I have dedicated my life to witnessing intergenerational poverty and trauma—a process that has enriched me professionally but that requires an incessant, unpleasant reconnection with the painful past I overcame—the most fundamental is that I dream of a world in which no child suffers for our country’s greed.

In this era of minority rule, the American left has wisely acknowledged the limitations of simply telling people to vote. Some elected bodies are so intractable, in fact, that even holding office may be ineffective. Chloe Maxmin, an environmental activist who in 2018 became the first Democrat to represent her rural district in the Maine state legislature, was a rising political star who wrote, with her campaign manager Canyon Woodward, a well-received book on renewing rural politics. Yet Maxmin herself, now the youngest female state senator in Maine’s history, announced earlier this year that she would not seek reelection. For now, she told me, she sees more potential to affect change in movement-building. She and Woodward have founded a non-profit, Dirtroad Organizing, to empower rural people and combat polarization.

In June 2019, Warren emailed me after receiving my thank-you card, which had expressed with some sadness that running for Senate wasn’t right for me—at least not for now.

“Sarah—I got your very generous note,” she wrote from the presidential campaign trail, while her candidacy was soaring in the polls. “There are many ways to serve.”

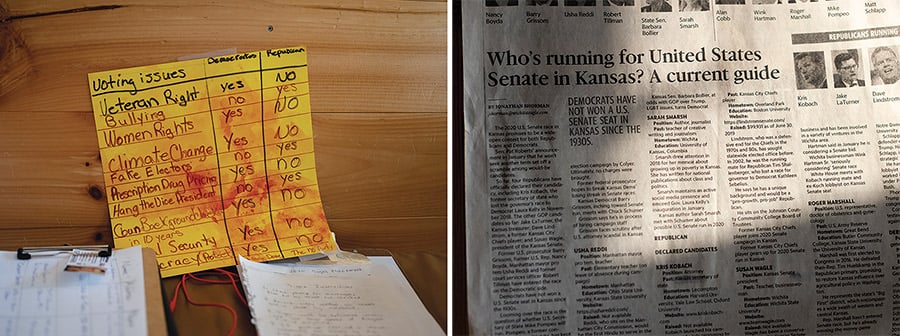

I never officially announced that I wasn’t running, and my spirit sometimes lingered along the road not taken. Several declared Democratic candidates withdrew from the race, making way for former Republican and pro-choice state senator Barbara Bollier to win the primary. Despite Bollier’s impressive fundraising, Representative Roger Marshall defeated her in the general election by eleven points. In one of his first acts as senator, Marshall would join a small handful of colleagues who voted to overturn the presidential election results just hours after the deadly siege on the Capitol by Trump supporters. Alongside my fellow Kansans, I mourned this development in a unique way, and I winced at the many instances to come in which one Senate vote could have changed the world.

I took heart, though, noticing in videos that Ocasio-Cortez had Heartland on her bookshelf. More recently, I cheered when, in the country’s first vote on reproductive rights following the overturning of Roe v. Wade, Kansans across party and urban-rural lines roundly defeated a proposed amendment to the state constitution to eliminate the right to an abortion—lifesaving confirmation of the nuance that my writing had insisted was true.

Throughout, a knowing abided. As society tears, some Americans will emerge, dramatically altered, from a stars-and-stripes cocoon. Some of us, though, will find that the next right thing to be is the thing we have been all along.

In May, before Thompson’s diagnosis and my temporary reinvigoration, I’d gone to Iowa to give talks in Des Moines and Iowa City. The latter, a ticketed fundraiser for the public library, paired me with the journalist Connie Schultz. I had long admired Schultz, a first-generation college graduate who grew up in working-class Ohio and won a Pulitzer Prize in 2005 for her columns in Cleveland’s The Plain Dealer, and she had sent me encouraging messages about my journalism before Heartland was published.

When we met in the hotel lobby before the event, Schultz’s husband, the Ohio senator Sherrod Brown, was at her side. Earlier in the year, while exploring a bid for the 2020 presidential nomination, Brown had gone on a four-state listening tour with the theme “the dignity of work”—an unfashionable idea among privileged anticapitalist leftists but one that would resonate for the many proud laborers I know. I had been flattered to learn that he’d given his daughter Heartland for Christmas. In March, Brown had announced he would remain in the Senate. This disappointed many but inspired praise for Brown’s humility at a time when a dizzying number of Democrats were contending for the White House.

As people streamed toward their seats, Schultz, Brown, and I chatted in the greenroom. I found myself discussing my conundrum with real-life avatars of the vocations I was choosing between: an influential writer concerned with working-class issues and a U.S. senator concerned with working-class issues. As a couple they had taken the two diverging paths before me and wrapped them into a domestic double helix—experiencing together, every day, the line between journalism and politics, between temperaments that carved separate yet kindred pursuits toward the greater good. Schultz had taken a leave from The Plain Dealer in 2006 to avoid conflict of interest while on the campaign trail with Brown. He respected her work in kind; when Schultz wrote unsparingly about their campaign experience in the 2008 book And His Lovely Wife, Brown didn’t ask her to delete or change a single thing. The two seemed sent by the universe to help.

“You have to want it,” Brown told me. This sentiment seemed an unhelpful cliché until I unpacked it: Proceeding from a sense of duty or sacrifice, or because of other people’s expectations, was no good. About the presidency, Brown said, “In the end, I didn’t want it bad enough.”

The only reason to do something so drastic was raw desire. When people ask how I decided to become a writer, I explain that I never decided. I started narrating the world around me in my head at around age six. Years later, there was no fretting over journalism’s low pay, no hesitation about the occupational hazards of being a woman in a man’s world. That I had been hemming and hawing over the Senate race for months suggested that it just wasn’t my calling—not then, anyway, and maybe not ever. I required no poll, tour, or consulting firm to determine as much.

This conversation with Brown and Schultz was the first clear validation I had received for what, regardless of my internal kicking and screaming, I was about to do—decline attention, power, and opportunity for reasons I had not yet entirely articulated even to myself.

I didn’t share my intentions aloud, but Schultz abruptly met my gaze in a way that no one else had throughout my many conversations about the race.

“You’re not running, are you.” Her inflection voiced a statement, not a question.

I smiled, caught off guard. Everyone else seemed to assume that I would—because, apparently, who wouldn’t? I wasn’t sure what to say.

Schultz stared at my face for a moment and nodded, with a spark of amusement in her eyes.

“You’re a writer,” she said.