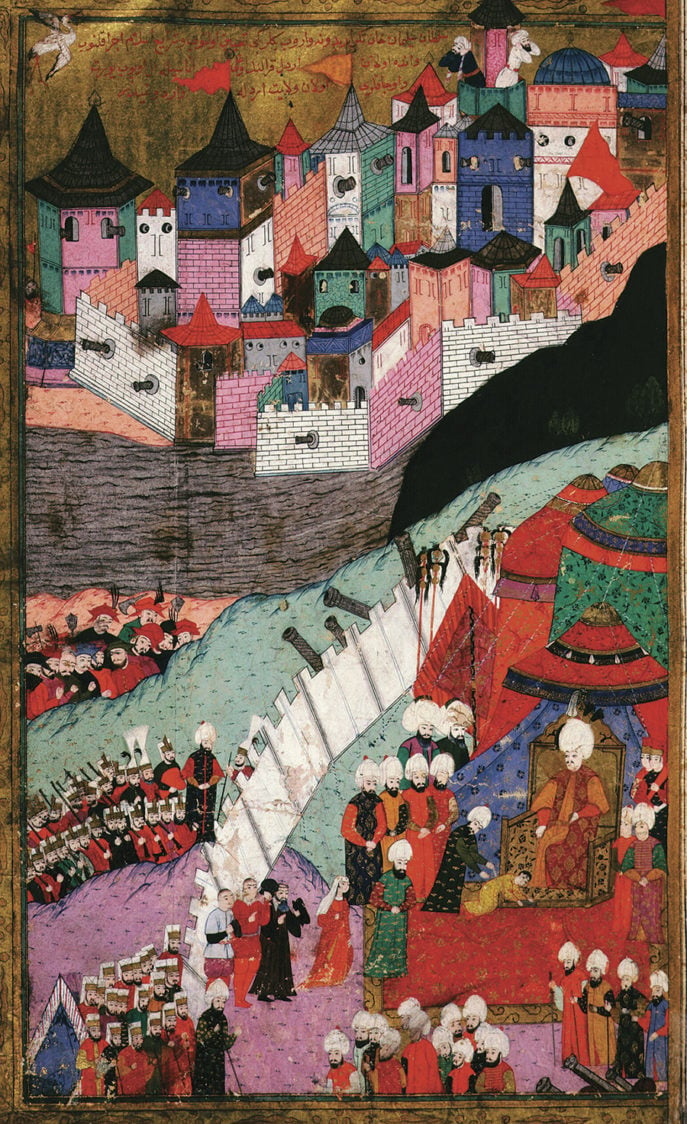

The Ottoman army capturing Belgrade, from a sixteenth-century manuscript © Gianni Dagli Orti/Shutterstock

The finest historical fiction—Hilary Mantel’s Wolf Hall trilogy, for example—renders the strange grippingly familiar; so too do those rare historians whose novelistic understanding of their subject brings it to life. Christopher de Bellaigue, an acclaimed historian of the Middle East, has done just this in The Lion House (Farrar, Straus, and Giroux, $28), a vivid, cinematic account of the rise of Suleyman the Magnificent that is written almost entirely in the present tense. The book unfolds through the eyes of his closest courtiers and allies, and through them we watch as, in just fifteen years, Suleyman comes to rule a domain that spans three continents and comprises some twenty-five million souls.

Sultan Suleyman the Magnificent, “melancholic, generous, proud and impulsive,” was the great ruler of the Ottoman Empire from 1520 to 1566, the caliph or “leader of the world’s Muslims.” De Bellaigue’s history, however, is concerned with the first portion of Suleyman’s reign, and ends with the assassination of Suleyman’s grand vizier, his former slave and lover, Ibrahim Pasha of Parga, who is known as “the Frank,” in 1536.

Alongside Suleyman, the Frank emerges as one of this story’s principal characters, a man “unappeasably alive . . . dressed more splendidly than his master.” A Muslim convert (born a Christian), he is in youth adored by his master, and with the investiture of Suleyman, Ibrahim of Parga is elevated also: he becomes head of the privy chamber, chief falconer, and head of the palace administration. He “sleeps with his lord, head touching head,” and “whatever Ibrahim wishes done, whether it is to be entertained by midgets, to be read aloud the medical treatise of Ibn Sina, or to partake of a peach, it is done.” In 1523, Ibrahim is controversially elevated to grand vizier, “one of the most powerful positions in the world,” and is granted command of the army of Rumelia. Though favored by Suleyman, Ibrahim is widely disliked, as he “trespasses into domains that aren’t his,” meddling in the sultan’s finances and claiming responsibility for law and order.

We also meet Ibrahim’s close ally Alvise Gritti, a successful Venetian businessman in Istanbul, a man who “doesn’t see commerce as separate from power but as its agent of propulsion.” Alvise is the beloved bastard son of Andrea Gritti, who is appointed the doge of Venice in 1523, only months after the Venetians learn that the Ottomans, under their new sultan, intend to battle Christendom to its heart, placing Venice squarely in the empire’s sights.

Relatively late in the book, we encounter Hayreddin, as he is known to his men (“boon of the faith”), also called Hizir or Barbarossa, who was appointed by Suleyman’s father as the “High Governor of the rather theoretical Ottoman province of Algeria.” Chiefly, though, he is a pirate, and a successful one, providing Suleyman with a much-needed naval force to combat the Ottomans’ seafaring enemies.

De Bellaigue follows with exhilarating clarity and suspense the era’s broader battles across Europe, North Africa, and the Middle East, and the individual trajectories—grand ambitions, rivalries, betrayals—of these outsiders in Suleyman’s court, a place rife with intrigue and back-stabbing, rich with colorful characters, each pressing their advantage. The tale of Ibrahim Pasha of Parga’s rise and fall forms the spine of The Lion House, as it shows us the evolution of Suleyman, his maturation into a king ready to sacrifice those nearest to him. “He thinks of his father, Selim, who killed men many times, so many times, and died in his own bed,” de Bellaigue writes. “For isn’t that the strongest desire of the greatest king: to die in bed?”

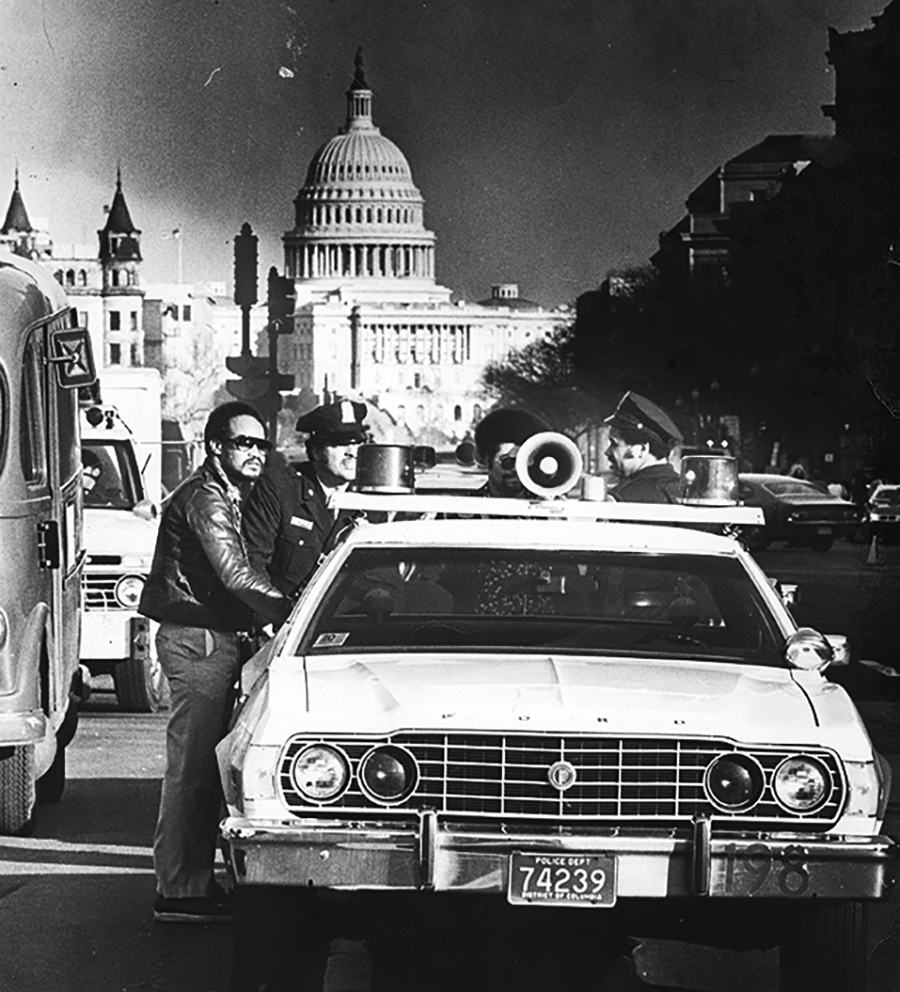

Police on Pennsylvania Avenue during the Hanafi siege on March 9, 1977 © Stan Grossfeld/Boston Globe/Getty Images

In American Caliph (Farrar, Straus, and Giroux, $30), the journalist and professor Shahan Mufti undertakes an analogous task: he, too, seeks to illuminate the history of a caliphate—not that of the Ottoman caliph, a title abolished by Atatürk in 1924, but rather of an American caliph, a position aspired to by more than one Black Muslim leader in the late twentieth century.

The book tells the extraordinary story of a dramatic hostage incident that occurred in Washington, D.C., in 1977. A group of heavily armed Black Muslims known as the Hanafis attacked the headquarters of the Jewish organization B’nai B’rith International, the city’s Islamic Center, and the District Building near the White House, holding almost 150 hostages for two and a half days. This early episode of homegrown Islamist terrorism serves as the fulcrum for Mufti’s illumination of the importance of Black Muslim groups in this country from the Fifties onward. Even as they engaged in factional infighting at home, American Muslim leaders including the Nation of Islam’s Elijah Muhammad, Malcolm X, Muhammad’s son Wallace, and the Hanafi Muslim leader Hamaas Abdul Khaalis sought—and in some cases gained—alliances and support from governments and religious leaders in Muslim countries around the world.

During this period, Mufti explains, “the Middle East had gone from a fringe American concern to a central focus of both American policymakers and filmmakers.” In the wake of movies such as Lawrence of Arabia, a young Syrian-American filmmaker named Moustapha Akkad was determined to make a biopic of the prophet Muhammad, “positioning himself as the Arab who would tell the Muslim story.” Mufti follows Akkad’s efforts to get the film produced, demonstrating the growing cultural presence of Muslim stories in America.

And yet the release in 1977 of the colossally expensive Muhammad, Messenger of God, almost ten years in the making, proved the catalyst for the Hanafis’ act of domestic terrorism, “to this day, the largest hostage taking in American history.” Depictions of the prophet have been “a widely accepted taboo for a thousand years,” and many Muslims around the world protested Akkad’s project; but for Hamaas Abdul Khaalis the release of Akkad’s film was the last straw.

Khaalis, the founding leader of the Hanafi Muslims, stands at the heart of Mufti’s complex book. He was born Ernest Timothy McGee. Raised in Gary, Indiana, Khaalis moved to New York in 1946 at the age of twenty-three. He had trained as a drummer, and was keen to play jazz in Harlem. Professionally successful—he toured Europe with the Harlem Madcaps in 1947—he also got married and became a father. He graduated from City College in 1951 and took graduate classes at Columbia. Harlem was also where Khaalis was first exposed to Islam, which was “for many . . . truly the religion of Black empowerment.”

Initially, Khaalis embraced the Nation of Islam. Recommended to Elijah Muhammad by Malcolm X, Khaalis moved to Chicago, where he became “the de facto national secretary of Nation of Islam, in charge of operations across the country,” but in 1958, he broke with Muhammad and returned to New York.

Khaalis there became the disciple of a Bengali mystic named Tasibur Uddein Rahman, who believed that the Nation of Islam was “a sinister plot masterminded by Zionists” and deemed Khaalis his caliph. After Rahman’s death in 1967, Khaalis and several others registered the Hanafis as a nonprofit organization. Among their converts was a basketball player named Ferdinand Lewis Alcindor Jr., renamed Kareem Abdul-Jabar, who would help finance the organization for years.

Khaalis’s great and catalyzing tragedy occurred in January 1973, at the Hanafis’ headquarters in Washington. In retaliation for Khaalis’s criticisms of the Nation of Islam, an affiliated group from Philadelphia broke into the building and brutally murdered seven Hanafis, including members of Khaalis’s family. Over subsequent years, working, despite great trauma, to assist the authorities, Khaalis and his family fought to see their attackers brought to justice, with mixed results. But as Mufti notes,

In the end, after a lifetime of playing a hand that had been dealt crooked, after getting doors slammed in his face for speaking the truth . . . after years of watching the gears of the American justice system chew up family members . . . it was a movie poster that pushed Khaalis over the edge.

When Khaalis and his followers launched their attacks, one of their key demands was the removal of Akkad’s film from circulation.

Mufti does a terrific job of putting these stories in the context of the times, of events and tensions both national and international. The Nation of Islam was, for example, endorsed in 1959 by Egypt’s president, Gamal Abdel Nasser. Malcolm X—in Mufti’s eyes, “the closest anyone had ever come to being the caliph of American Muslims”—was recognized by the rector of Al-Azhar in Cairo in 1964.

In the end, it was the intercession of three Muslim ambassadors—from Egypt, Pakistan, and Iran—that persuaded Khaalis to release the hostages. And yet, as Mufti notes in the book’s closing chapters, by the time of the 9/11 attacks—“a new era for Muslim America, darker than any before”—no singular leader emerged. Muslim America remained “as fragmented and fractured as ever,” and the “chasms between African American and Muslim immigrant communities had only widened.” Khaalis himself was denied parole six months after the World Trade Center attacks, and died in prison at the age of eighty-one. There was, Mufti writes, “no record of a public announcement of his death nor any public obituary.”

The Battle of Køge Bay, 1677, by Anton Melbye

A Line in the World (Graywolf, $16), by the luminous Danish writer Dorthe Nors, offers the antithesis of de Bellaigue’s or Mufti’s intense histories. Nors, known primarily as a fiction writer, here embarks on a languorous and evocative tour of her native Denmark, from Rudbøl at the German border to Skagen at the northernmost tip. The dramas of the past are evoked not so much through individual characters as through their traces—buildings, ruins, shipwrecks—and this westerly Denmark is less the land of Hans Christian Andersen fairy tales and sleek Georg Jensen designs than a place of ancient landscapes steeped in myth.

“In the Middle Ages there was a strong centre of power in Viborg, in central Jutland,” Nors writes, “but the balance tipped towards Copenhagen, and it’s never the losers who get the chance to write history.” While “women’s relationships with the landscape were relatively undocumented,” Nors has now “claimed the right to see and to describe.” Furthermore, she asserts, “The landscape must have an essence that, in itself, can speak”—and this, perhaps, is the heart of her project. People aren’t wholly incidental to the narrative. Nors introduces us to a variety of colorful characters, and shares vivid memories of her family’s time in a cabin on the coast south of Thyborøn. But in a way that recalls the work of Barry Lopez, nature is at the heart of this beautiful book, framed in essay-like chapters, superbly translated by Caroline Waight.

“Up there the woods were full of honeysuckle, tiny springs with water lilies, ferns, sparrow vetch and wood sorrel,” Nors writes of a midsummer walk at Tornby. “Brown tracks bored into green tunnels. Somewhere among the trees I stood silently for a long time, watching a deer with a fawn.” And later, she describes a visit to Bulbjerg, which “protrudes over the sea, white and dripping. Along the beach are smooth-honed limestone cliffs. They look like the bones of a giant.” Of the flats in the Wadden Sea, she writes, “These channels and their tributaries, the tideways, ran like juicy veins into the mudlands.”

The landscape is seamed with histories: Nors celebrates the matriarchy of Fanø, the women’s Frisian uniform, and “one of the most beautiful traditional dances on earth: the sønderhoning.” She tells the story of her elderly friend Knud Sørensen, a poet and trained surveyor with no belief in magic, who drove one night to visit the medieval Børglum Abbey and could not find it: because, she posits, the abbey had briefly climbed into eternity. Accompanied by Signe Parkins, the book’s delightful illustrator, she visits a series of churches adorned by antique frescoes, “on a quest for things that transcend time.” She hymns “the seaborne trio: the Angles, the Saxons and the Jutes,” who traversed the North Sea, and later the Vikings, observing that the “number of Danish words in the English language suggests that at least thirty-thousand Scandinavians settled in England towards the end of the ninth century.” And she laments the British ships wrecked along the shore in 1811, the St. George and the Defence, with the loss of more than a thousand lives.

She observes, too, the transformations of the recent past and the present, such as the disturbing effects of the Cheminova chemical plant opposite her family’s cabin. “In the 1970s, especially, we had to drive home to our real house sometimes, far inland, if the wind blew in from Cheminova,” she writes. “The flounders, which the grown-ups ‘trod’ with broomsticks fitted with nails on the end, had strange wounds, but we ate them anyway.” Or, of more recent date and less disturbing, she records the avid surfers at Thy National Park, known as Cold Hawaii; and, looking to the future, the hopeful construction of “forests of wind” at Horns Reef, off Denmark’s westmost point: “Something important was beginning.”