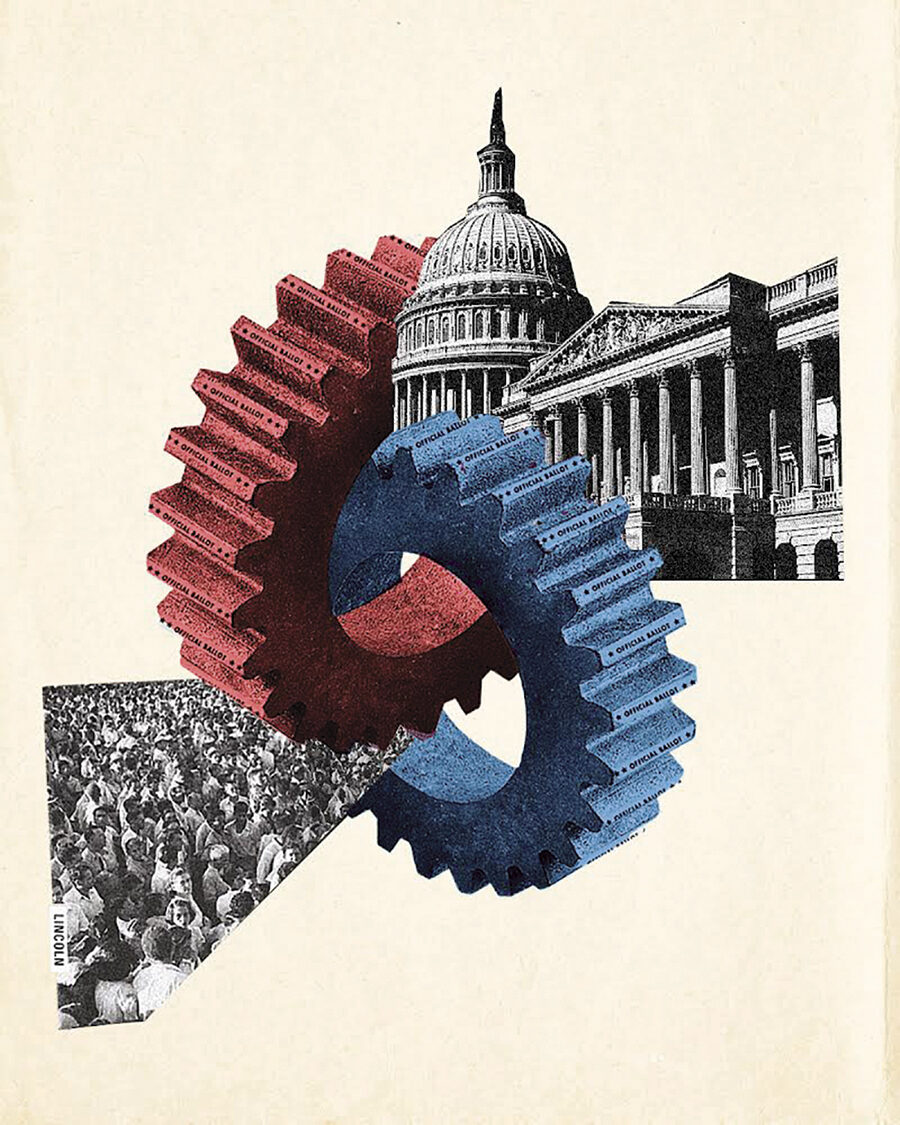

Party Walls

Collage by Lincoln Agnew

Conventional wisdom holds that our political moment is, in Joe Biden’s words, “not normal.” Thus, the usual political lessons to be drawn from such historical events as the New Deal or the United States’ entry into the world wars are supposedly irrelevant now. This is surely a dangerous misconception, especially when promoted by those who remember the past incorrectly. That is why the work of Walter Karp, a passionate scholar of American political history who offered a bracing antidote to the popular beliefs of his own era, is so useful today.

A generation ago, Karp served as a contributing…