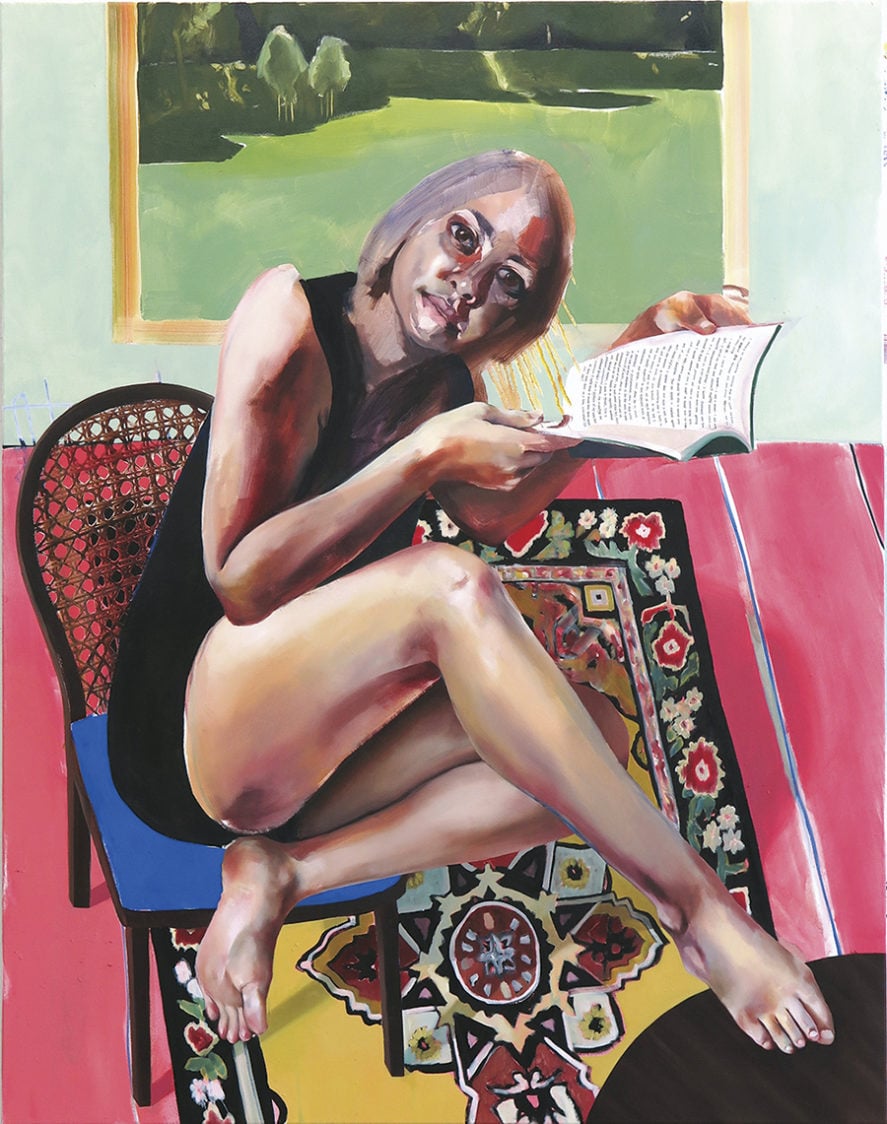

Being on the Grass, by Ellen Akimoto, whose work is on view this month at Galerie Rothamel, in Erfurt, Germany © The artist. Courtesy Galerie Rothamel, Erfurt, Germany

The Loud Parts

Angie said through convoluted gasps brought on by racing Adderall thoughts that Saint died at his desk so Jean could get his job. Jean insisted between tangents of laughter that she didn’t find it the least bit funny and privately wondered why Angie always wore such itchy sweaters when she was prone to worry raw every sensitivity imaginable. Her companion looked as if she were made of gold and worshiping herself, the way she slipped her hands up and down her arms in a perfect, hungry rhythm.

“I thought we were having a serious conversation!” cried Jean. Angie rolled her eyes and picked at her lip. They were roommates, but spent many days, like this one, at Angie’s parents’ amply chambered burrow on the Upper West Side, where she had her own wing, like a rock star in a hospital: bed, bath, and a little someplace extra for the well-wishes to accumulate (Jean slept here). Angie grew up with plenty of money, Jean did not—though not quite poor either, in a suburb of Pittsburgh with two brothers, parents apolitical, tolerant, then separated and largely absent, the father out in San Diego, mom remarried to a gregarious, yelling man. Angie often thought she might have turned out better if her parents had been less involved in her life, or if there were several states between them, rather than just a few walls. When Angie expressed this sentiment, Jean would point out that despite the proximity, her friend hardly saw her parents. Anyway, it was Jean who might have had cause to envy the close-knit self-sufficiency Angie’s parents had modeled for her, were she not so impervious to wanting what other people had.

The women had met at the Manhattan college Jean graduated from six months early and Angie not at all. Jean easily spent more time at Angie’s parents’ apartment than she ever did on campus.

“I’m not saying that because I believe it,” continued Angie. “I’m saying it because my sister does. Her sixth sense is professional management. She has a talent for keeping the great wheel of comeuppance and comethroughance functional and dynamic and fucking crystal.” Angie, a born Translator of Grievances, let her eyes bulge and recede in a fixed pattern like the hands of a magician casting a spell over an empty hat.

“Maggie told you that—that Saint’s death has to do with destiny?”

“Please, you know she keeps her distance. But I can just imagine how she’s taking all this. I’ve had to sharpen that faculty of late, given how little she tells me about her life. She isn’t a good person.”

Maggie was twelve years older than Angie and had her life conspicuously together. She ran Readsome Enterprises, a literary agency she’d founded nearly a decade prior with the considerable assistance of her family’s money, and which Jean had worked at for the past two years, beginning as an intern. Angie hadn’t thought twice about recommending her friend for the job. Jean needed one, and she would have accepted whatever came her way.

It was a small agency with six employees. There were five agents and one associate who worked closely with Maggie and was thought of as an agent-in-training (this was the higher-paying assistant job Jean had just been promoted into). All of them fussed over a modest list of clients who regularly didn’t write. Despite this, the group got written about in the press quite a bit, and had more cachet than the imposing corporate outfits. None of this was due to Saint’s passing, which had been kept out of the media, privately gossiped about and mourned, even though it occurred in the office.

The firm’s notoriety rested, rather, on the mysterious personality of Maggie’s husband, the novelist Teller Fane. A famous recluse in the era of influencers and data mining, Fane had for decades managed to evade the public eye—but not the rampant speculation, stoked by rumors of sporadic excursions into the city to visit his wife or carry out some other unadvertised errand. The New York Post once reported him dead due to an imprudent, unsourced outburst on legacy media Twitter. The little that was known about him was picked over ravenously in every conceivable outlet, from literary magazines to Reddit threads. It was said that he was vegan (but his characters were always eating meat?!) and that he didn’t write any of his novels himself because Teller Fane was actually

the name of a mind-control corporation, or a different, even more ingenious, male novelist.

No picture of Fane past the age of twenty-five existed on the internet, and he’d be turning forty-eight that spring. The image that accompanied most coverage concerning him, the one that graced his book jackets, had been taken at a bar on Grand Street in the late Nineties; it featured a pained smile, two tumblers of scotch on the hazy bartop behind him, and a lit cigarette. It didn’t exactly do him a disservice to remain twenty-five forever. In those early days he’d looked like a young Peter Falk—rather handsome, if you’re into that sort of thing.

For the past two decades, Fane had been steadily working away on what he considered a single project of interlacing fictions called The Archipelago. In each of the novels, his characters occupied an insular conceptual or physical terrain. One was set on a private island owned by a billionaire which plays host to sinister tech summits, celebrity supper clubs, and Travel Channel specials; another on a small island nation that is rapidly disappearing into the sea because of climate change; another in a prison; another deep inside the mind of a philosophy professor; another on a large volcanic landmass thrust up from the sea in 1652 and settled by a cabal of insane Dutch explorers who eat all the strange roots and animals they find there, die in many new and exciting ways, and are written out of history.

The new books arrived every year or two. Most of them were fairly short and might even have been marketed as novellas if someone else had written them. Characters from one novel sometimes wandered into another, but the frame of each individual work was tight. Some of his sentences were very short indeed, and this too attracted little comment, much less than the invisible life he led. None of the books were set in Manhattan, which was either a wasted opportunity or a rule of thumb. It was said that Fane’s work was inspired by The Human Comedy, and literary Twitter sometimes referred to him as “Sad Balzac.”

Angie, of course, had a different take on the matter. “The island theme is nothing but a gimmick. What he writes are books about people who don’t go anywhere.”

And Jean would retort that some people really don’t.

This was a sentiment Angie claimed not to understand, although Jean couldn’t see why. Angie resembled her ambitious sister in some respects: a hot streak of passions, terrifyingly competent. Sleep was her enemy and she didn’t seem to need much of it. Beautiful language brought on fevers, music showered paroxysms of ecstasy and despair upon her head, mediocre television left her colder than a rock floating in space. Only, unlike her sister, she had no schedule, no job, no man, no clue which of her drastic moods she’d awaken to tomorrow. Without a socially legible purpose to her days, she and her sister looked to the world like exact opposites.

“I checked out Saint’s Instagram,” offered Jean. “Hundreds of pictures—friends, Europe, trees—but only a couple of them with him in it. Nothing tagged.”

“Like he was making a guest appearance on his own show.”

“Maybe he didn’t like himself.”

“He was supposed to be a teetotaler with his condition, that’s what he kept telling you, right? Did he drink so much because he knew his heart was too erratic to take it?”

“I don’t think so. Nothing points to it. He just worked more than he needed to. Sometimes I think maybe he was celebrating a little, you know? Testing something out, trying not to be afraid.” Then Jean added, in order to show herself capable of sympathizing with Angie’s depressive cynicism, “I’m surprised more people aren’t discussing it on Twitter, though.”

Angie scoffed. “I’m not. He was an assistant and only had like two hundred followers.”

“But he went to Harvard!”

“Oh, but Jean, you must know by now that where I’m from—and where you’re heading at a stunning velocity—having gone to Harvard is even more common than wanting to die.”

Jean gave a conciliatory smile and said nothing, feeling it was kinder to hold her tongue. Five days ago, before Angie had left the apartment they shared in Crown Heights for another of her regular West Side respites, Jean had discovered the pieces of a torn page in the trash, mixed in with leftover oatmeal and toothpaste packaging. A line had been drawn through the words “not to live.” These were words Jean had heard Angie say out loud before, many times. “What I want is not to live anymore.” Words that hung in the air, where they could not be struck through and binned. Jean first assumed that the scraps came from a letter, but they could just as easily have been slivers of a diary entry Angie wished to retract from the record.

The fragments disturbed Jean, but not deeply. They conformed to Angie’s strict embrace of excess. Even the crossed-out words were excess: a morbid sentiment, a renunciation, followed by physical repulsion. All her passions came to this, eventually. Crossed out as if in an attempt to multiply them.

Still, Jean followed Angie to Manhattan the next day. She made sure Angie was on her feet by the time she left for work. On her way back from the office, she picked up dinner for both of them, something healthy, which Angie could have for lunch the next day if she was out for the evening. Or, if she was around, Jean would happily chatter with her until midnight, when she would crash from the effort of it all.

At the same time, Jean admitted that their relationship—the whole situation—felt uniquely comfortable. She even loved the Upper West Side, which Angie complained about incessantly, in a manner that was funny and charming but inevitably spoiled. Locals walked the streets with worry plastered on their faces, their peacoats, faded Patagonia, and beat-up leather jackets oddly lumpy, as if stuffed with D’Agostino plastic bags. This frumpiness was the cost of admission to dwell for decades in the Kingdom of the Fair. Everyone felt a little guilty, but then again they were in therapy for that. To Jean, a tourist, it was pleasure itself. The warm interiors where one could hole up all day, the auspicious tartines she ferried back from local bakeries, the brisk commute to her midtown workplace on any of five efficient subway lines.

The only downside as far as Jean was concerned was the yearning she felt each time she finished the excursion, her fate sealed up again in the sepulchral Kingdom of Obligation, to quit her job and retire here. It wasn’t as if their apartment in Brooklyn was squalid. It could have been fine, but the noise from the street and the train got in, the lighting was cruel, the contents of her closet were upon the floor, the laptop was always open to some meaningless celebrity scandal that sucked the time away, the dishes piled up and made Jean want to forget herself.

“I never knew someone who died,” said Jean. “Nobody relatively young at least. I guess I’m only twenty-three.”

“So am I!”

“But you didn’t know anyone who died suddenly like that, did you?”

“Yes I did! A girl I went to high school with died in a motorcycle accident a year after graduation. And then there’s my brother-in-law of course.”

“Only he isn’t dead. Sorry about your friend.”

“If she’d been a true friend you would have found out about her ages ago. More of an acquaintance. Thanks all the same. And concerning my brother-in-law, I’ve come to understand that disappearance is death. Strangeness can be, too, which is what my sister and my entire family have become to me ever since he broke into it, the stealthiest way one can: he just opened the door and walked right in. Then, having cultivated that famous sense of familiarity, he snuck out the back, leaving everything apparently untouched. But, underneath, nothing is the same. It’s all turned to junk!”

“Not much respect for the dead.”

“Try getting respect from them first. He hasn’t spoken a word to me in ten years, meanwhile my sister exists for him alone. She barely pretends to have a relationship with me anymore. Worse than dead, he’s death itself!”

For about three months, Angie had been seeing a painter by the name of Frank Wade. He was only twenty-six and had already managed to gain a modest reputation, not to mention a couple of sales, enough to disappear for long periods of time. The occasional graphic design gig meant he never needed to call in favors from any of his willing friends. A penny saved is a penny that can’t be thrown at you in violence or disgust later on.

On their first date, Frank told Angie he was possessed by a demon, possibly several demons. The demon would show him visions of what to paint next, communicating in the angles of sun rays and dreams. In bouts of cloudiness and dreamlessness he was frightfully abandoned and, by his own admission, not fit for human company. Due to his inconstancy and Angie’s growing attachment, their flimsy relationship operated on a timescale of eras coalescing into matters of historical record. At least for Angie.

Jean was up at the crack of dawn listening to Angie recount her much-awaited seventh date with Frank. It had been three Fridays since Saint’s death.

“His paintings have gotten more abstract since I met him. Blue, green, and black; a teensy bit pink. He tells me they’re dragons. That’s a boundary I don’t respect. To me they have nothing to do with dragons at all! I think he’s depressed, and in love—with me, hopefully. He says he wants to take me on a trip. He said ‘anywhere in the world,’ which is very lenient, don’t you think? I suggested the Balearic Islands and he got all mad with joy. We fucked three times. Well, twice. Why not Majorca? That’s where Robert Graves had his printing press. Nadal is from there. I wonder if his little town hosts an annual festival in his honor. We could plan the trip around that. As if it were Mardi Gras or an eclipse. . . . ”

Jean let her go on—it had been hard enough for Angie to get over the last one, Daniel, the guy who held a knife to her throat while they made love, then moved to England to patch things up with his wife—but only to a point.

“Listen to yourself! Hear the words coming out of your mouth. You’re so fucking horny for . . . what? . . . this pipsqueak artist guy? Can’t you—”

“Yes, I want his cock permanently installed in my mouth, who cares? The only thing hornier than having sex is not having it. Meditate on that, let it fill you with fuck-less, dick-less inspiration, or whatever it is that gets you off.” Angie writhed with laughter.

For a moment Jean wanted to love anything as much as Angie loved this twenty-six-year-old RISD dropout who made even his closest friends call him on a landline. Then the desire passed, and that splendid coolness she relied on to shepherd her through lethargic days at the office and evenings of placid reading returned to her. She retrieved Angie’s English muffin from the toaster, placed it on a clean plate, and left for work.

Several inches of snow had fallen the night before. The city was slow and empty on its face. Belowground, on her morning commute, the usual frazzled mush of passengers and gray water congealed.

She was third to arrive at the office, behind Maggie and another agent. It was possible the rest of the staff wouldn’t bother to come in at all given the nasty turn in the weather.

The office’s atmosphere revealed nothing about the recent tragedy that had unfolded there. Maybe it was the serene sliding glass doors of the agents’ offices, which surrounded an open sprawl of desks. Maybe it was that one person occupied this central area now, and it was Jean, who had only been joined by Saint for a couple of months as he began his transformation into a bona fide agent. Kelly-green carpets, pale-yellow walls, light wood paneling along the edges of the glass doors, which matched the bookshelves framing an entrance to the elevator, soft light, desk lamps, like a classy pool hall where everyone just reads. Maybe it was the absence of mess (the cleaning staff had found Saint’s body). Maybe it was that an inappropriately large office for such a minor operation bred nothing but space between people; the very air was toxic to gossip, and sympathy, and dread.

An hour before Jean’s lunch break, Maggie Fane approached her desk. She had the mirthful, uncompromising gaze of a former party girl turned arts executive. Her abundant chestnut hair was kept out of her face with a single pin. Jean had never really tried to form an opinion about her, and she was starting to wonder whether Maggie was having that effect on purpose.

“It’s really great you came in today, Jean, thanks so much! What have you got going on this morning?” Maggie always spoke about jobs with an air of their being volunteer positions.

“Jonathan had to step out for a meeting, so I’m surveilling Norma Desmond.” This was the code name for Readsome’s most managed male client, who demanded that an agent watch him at all times during his weekday writing hours. Remarkably, the books did get done and were very sexually explicit.

“Nanny cam duty,” said Maggie with a sigh. “I find it relaxing, myself.”

“I find yoga relaxing,” said Jean.

“Office yoga, now that would be great for morale! Jean, I have a request to make of you. Feel free to refuse.”

“Okay.”

“I’d like for you to speak to my husband. Privately, I’ve been mourning the passing of Saint . . . and discussing it with my husband quite a bit.” Here Maggie left room for Jean to echo her distress, but Jean kept quiet. She was not one to unsettle silences.

“My husband has become interested in Saint. It’s for a novel he’s writing, the story of a man who is thinking of ending his life, or gaining an entirely new one. I told him that of everyone in the office you spent the most time with Saint. It’s rude of me to ask, I’m aware of that. We can just forget the whole thing if you’d like.”

Jean sensed that Maggie was being insincere, as usual. Of course the request seemed rude to Jean—in the sense that all work was an impertinence that placed her days in service to another. And it was rude to pretend as if there existed no other personal matters between them. As if she didn’t live with Maggie’s sister! But Jean wanted to talk to the famous writer and relay everything to Angie later.

“When would your husband like to speak with me?”

“Today would work well, if you’re amenable. Can I give him your cell?”

An hour later, he called. “Hello, Jean? This is Teller.”

The voice rattled Jean. It was delicate, with a hint of offense already taken, like a lace trim on an otherwise indefinite figure. It was not cerebral, and it was not warm, and it was not automated. The voice was a carcass. Its pitch was that of wind when it finally reaches a charming little house after miles of emptiness, then blows right past it.

“Hello, Mr. Fane. Yes, I was expecting your call.”

“You can call me ‘Maggie’s husband’ if you’d like. But I prefer Teller.”

“I don’t know. It’s weird to speak to a ‘Teller.’ ”

“Why do you think I never grant interviews?”

Jean laughed despite the engrossing formality of the situation. “Maggie said you wanted to talk to me about Saint?”

“I do. I know it’s a strange request, and perhaps a vulgar one. I don’t mean it that way. I just get curious about people, although I try not to involve myself personally with what I’m writing about. Of course, I know I’m writing about myself no matter how elaborate the fiction, but I never think about it. My process works for me. Or it usually does. For some reason I’ve been having difficulty lately. My wife speaks highly of you and your friendship with my sister-in-law. Stop me if any of this provokes thought or even pity in you.”

“I don’t like to interrupt.”

“Well, you’re young, you may get over that yet.”

“How do you know I’m young?”

“My sister-in-law is young.”

“Twenty-three is young?”

“On second thought, I’ve no idea. You’d have to get back to me in ten years with the answer.”

“Maggie said you’re working on some kind of melancholia project?”

Jean paused and, interpreting the lack of response as assent, went on.

“Well, as it happens, I didn’t know Saint well. I don’t have any special insight into why he died. Not a peep from his family. Nobody in the office was invited to the memorial. He worked here briefly. Of course, when a young person dies, people are bound to wonder if it was purposeful or a terrible accident. But I only know that it made me sad. Very sad. The days got quieter for a while, but already they seem more regular again.”

“Do you not feel changed by his death?”

“It’s hard to say. Maybe I will feel more changed by it in a week or even a year. Actually, I can tell you how I feel at this very moment. I don’t feel changed except that I feel things must change now, and I didn’t feel that way before.”

“Things in your life, you mean?”

“Yes, I think—do I have the right idea about your novel? You’re writing about someone suffering from depression, or who doesn’t want to live.”

“In a sense.”

“Then why ask about my life?”

“I would rather keep talking and not tell you.”

“But I would like to know.”

“All right. The protagonist of the novel is a popular writer—but not a known one—from a troubled background. He does suffer a breakdown, a deep depression, but it’s for a surprising reason. Or I hope it’s surprising. Someone he’d never thought about before or been intimate with, a colleague very much on the periphery of his life, disappears. And it sets off all these changes in him, which the people who have a financial interest in his functioning sanity try to subdue. The protagonist has some careless tendencies, mind you. He disappears from peoples’ lives all the time. Maybe the idea is terribly obvious and you can see where all this is going.”

“No, I can’t. I mean, I can’t see where the story is going. But if I didn’t know any better I’d say you were questioning me about my own mental state, not the circumstances of Saint’s death. I am the one who has of late suffered an absence.”

“That’s right. Like I said, I get curious about people sometimes. I apologize if my approach alarmed you.”

He seemed, to Jean, to leave so much out. She found herself wanting to take a step closer. Her phone was pressed to her right ear and her whole body was inclined that way, as if she were speaking to a man just on the other side of a wall.

“Strangely, I don’t feel offended at all,” she said. “Maybe I don’t have enough mysterious callers in my life. Or mysterious Tellers. But, look, I don’t want you using what I say about myself in your book.”

“You mean that I shouldn’t ask you about your life anymore.”

“I mean that . . . that you should call me anytime, if you have any further use for me.”

The Reader, by Ellen Akimoto © The artist. Courtesy Galerie Rothamel, Erfurt, Germany

As soon as she got back to her boss’s parents’ apartment, Jean began stripping off articles of clothing, one after another, taking care to crumple each item into a ball and fling it toward her bed as if it were a piece of garbage. Already it seemed that the memory of Saint had begun to fade, that she was shedding her light mourning garments in order to replace him at the center of Teller’s story.

Angie appeared in the doorway wearing a chenille blanket like a cape over her Norma Kamali bodysuit. Jean could see the shape of her hand beneath the blanket picking at a dry patch of skin around her collarbone.

“How was work?”

“Fine. Your sister’s being kind of a bitch.”

“God, yes, thank you! What did she do now?”

Jean savored this moment in which she might have dished about Maggie and her husband’s superficial interest in Saint’s death, Teller’s weird insistence on speaking with her, the possible implementation of office yoga in the not-so-distant future. It would be sweet relief from the day to slip into silky, conspiratorial chitchat. Besides, what she wanted to get into concerned Angie more than it did almost anyone else, and didn’t they talk about whatever was preoccupying them? Then her mind danced over the discarded scraps of paper. She pictured them assembled into a clean surface that would shout appalling words if only it had a mouth.

“Nothing,” replied Jean. “Literally nothing. I get fed up working there sometimes.”

“It’s so fake, right?”

“Totally. Being there reminds me of kindergarten arts and crafts. It’s supposed to be all fun and creative, but we have no control over our lives when we’re there. I had to watch Norma Desmond all day because Jonathan fucking checked out. Maybe he’s having an affair.”

“What makes you say that?”

“Nothing,” said Jean, who had only thought of it in that moment. “I just find the idea funny.”

“Well, I wouldn’t hook up with him. He’s like fifty and I find the fact that he works for my sister super emasculating. But I must admit he’s clever. All those crazy writers he coddles. He really figured out life—he never had to stop being a babysitter. And in a way, that’s the dream.”

Teller called again three days later, and again two days after that. Both times Maggie had been out at lunch. Do married people always know when their spouse is eating their lunch? Jean wondered. It thrilled her to think he was carving out a time in the day just for them. She wasn’t sure she had any affection for the voice, but she looked forward to how it broke the workday into pieces. The voice was her favorite task to complete. She didn’t presume that it took any particular pleasure in its encounters with her voice. It maintained a consistent tenor: asking, listening, explaining.

“What’s up?”

“Nothing’s up. Every day I work on my novel.”

“I’d ask you to tell me more about it, but I’m sure it’s, like, ‘top secret.’ ”

“Between us, it’s neither ‘top’ nor ‘secret.’ I’ll tell you the idea, if you’d like.”

“I already said I would.”

“And you’re allowed to laugh. Actually, please do. Deep breath. The year is 2045.”

“That is funny!”

“I like to open with a bit of dark humor. Waters are encroaching, coastal cities are sinking, war isn’t officially spreading, but violence is. Safety is the rarest of commodities, more precious than drinkable water, healthy food, education. The wealthy and professional classes have of course been spared the worst of it, and the worse the world gets, the better they feel by comparison. When the well-off feel bad, they tend to think about how terrible other peoples’ lives are, and this causes them to feel great happiness. Which is another way of saying they take pleasure in the pain of others. The expedient relations between empathy and sadism, the possibility that the two words might name the same feeling, is a large theme in the book. The protagonist, Charlie, is a screenwriter, a really successful one. He writes blockbuster movies and bingeable TV shows, and he’s been bought by one of those big streamers, Amazon but not. Disney Plus One. Well, Charlie has a mental breakdown. It seems to have been prompted by the disappearance of an assistant at the streamer’s legal department with whom he has interacted on occasion for a couple of years. Aside from that, the persistent problems in his life continue to dog him. He has an anti-authority streak and can’t stand that he’s sold out. He hates the police, and the superheroes he writes about who work with them. His mom died when he was young and his dad has been incarcerated in a mental health facility for twenty years, which makes even the fact of the breakdown particularly fraught. He’s unmarried, no girlfriends, no family he’s close with. Friends stick with him but enable whatever it is he wants to get into, which inevitably carries him away from them again. In the midst of all this psychic upheaval, the studio he’s obligated to serve asks him to write a script for a remake of 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea, an adaptation so loose it will obviate the need to buy rights to the book and make it easy to promote some of the company’s other products and values throughout the film. Management wants the project to home in on the individuality and adventurous spirits of the characters. Also, in embarking on this grand adventure, the denizens of this screenplay are discovering their own solutions to climate change, rather than whining to their elected representatives or blowing up pipelines. In short, they are men of their times and men for their times. Except that the Dr. Aronnax character will be played by a woman, to promote the idea that women can be in charge of their destinies too, and to diffuse any potential for homoerotic subtext. The studio has tentatively titled the project The French Canadian. Or Sea of Rogues. But my novel will be called The End of Charlie.” Teller paused. “Do you like that title?”

“It’s good, has a certain gravitas. Although between you and me I sometimes wish that novels would have more mundane titles.”

“For instance?”

“I don’t know, maybe something like Stop Doing That, The Countertop I Bumped Into, You’re Sitting on My Hair, Hold My Baby. But please go on.”

“Okay, very much noted. The last one was directed at me, yes?”

“It was.”

“The production company, always mindful of its bottom line and endeavoring to eke profit out of any opportunity, even a mental health crisis, proposes to book Charlie a week on a submarine spa, a wellness trend that has recently caught on, what with all the strictures on travel and veiled genocides over resource shortages. Once there, Charlie will receive counseling, kelp body wraps, massages, and immersion tank therapy, all in an atmosphere conducive to researching and writing.”

“You should call it Submarine Island.”

“I’m well aware you’re better at titles than I am.”

“So does he make it to the spa?”

“Yes, in fact, the novel is almost entirely set there and—”

“I don’t need to hear more. I like it. Tons of potential. Is it written yet?”

“Just the first draft, which is limp and unfeeling, which is what needs changing. But come on, if I knew you’d be this facetious about it, do you think I’d have bared my soul like that?”

Jean started giggling, waited for him to scold her, but he was really the most patient of Tellers. “Sorry,” she said. “ ‘It sounds brilliant’ is really what I should have said up front. I’m laughing because it sounds like a book Angie would like.”

“If she ever got around to reading it. Remember how she hates my guts? Not to mention my personality.”

“That’s precisely why it’s so funny! She loves Jules Verne, did you know that?” She wanted to add, Did you know she falls into depressions all the time over the tiniest details? At least they seem tiny to me, but I know not to dwell on the scale of her disturbances. And did you know the pain of hating one’s own self fascinates her as well, that she succumbs to it all too often?

She went on. “I guess I’ll have to be the one to read it. I guess it’s inevitable I’d read something of yours eventually. I’ll pick it up whenever it comes out in paperback.”

“Why don’t I send you a few pages this evening?”

“Really?”

“Sure.”

“But why?”

“Because you sound honest, beneath the sarcasm. And you’re not a stalker, blogger, hanger-on-er, my editor, my wife, or obsessed with me.”

“All right. How about a friend then?”

“A friend.”

On her belly with her feet in the air, Jean was gazing for the hundredth time at the lower rungs of Angie’s bookshelf, which lined nearly an entire wall of her bedroom. This position allowed her to examine the greatest number of books, since several more were gathered in fat teetering piles on the floor.

“I just realized I’m being a bookworm,” she shouted at Angie, who was lying on the bed with her laptop open on her stomach. “I’m being a revolting little bookworm crawling across your floor looking for my next great read. Isn’t it pathetic? Don’t you just want to squish me with your beautifully manicured feet?”

“No. You know I hate feet!”

“Oh my god, they’re your own feet!!”

Angie slammed her laptop shut and sat up.

“Want me to help you pick something out?”

“That’d be great.”

“Cool. I’m really gonna curate this experience for you,” she proclaimed, dangling her fingers by her face, like she was making a tiny marionette walk nowhere. “What are you in the mood for? Give me, like, three words to go off of. Any part of speech.”

“I don’t know.”

“Not good enough. Just say the first three words that come into your head.”

“That’s a lot of pressure!”

“Is it? Just give me one word.”

“Um.”

“Yes?”

“Um.”

“First word that comes into your head. Come on, you were just speaking in complete sentences five seconds ago.”

“Well, okay, um—worm?”

Angie stared at Jean with blatant disgust, then blinked hard. “Is that really what you want to be saying, Jean? You want me to curate for you some literature inspired by ‘worm.’ Is this what you’re telling me?”

Jean sat up straight, too, on the floor, and made a show of gathering her composure. “That’s a good point, Angie, a really good point. I don’t want my reading experience brought to me by ‘worm.’ What if I tell you, instead, what I don’t like to read. I’ll keep listing stuff until you tell me to stop and we can take it from there.”

Jean had the sensation of throwing sopping red meat to a starving dog.

“Yes, amazing. Okay, then go: what do you not like to read?”

“All right. I’m taking a deep breath, because none of this will be easy for you to hear. So, for starters”—for dramatic effect, Jean paused for almost a full minute, which Angie, in her hyper-attentive state, seemed not to notice at all—“I don’t like English detective novels.”

“Really?! But have you read—”

“I don’t like American detective fiction either.”

“REALLY?”

“And I don’t like adventures at sea. Actually I don’t like any plots that involve boats.”

“What the fuck, you can’t be fucking serious—”

“I don’t like stories set in the suburbs. Or the future.”

“How are those things even related in your mind, like—”

“And I don’t like leather jacket stories.”

“What, you mean expensively bound litra-ture?”

“You know perfectly well that’s not what I mean. I’m talking about the kind of story that sounds like a man in a leather jacket is explaining the most mundane details of his day to a person he considers an idiot. The clouds moved, the heart pumped blood, the stoplights flipped interminably red and green. It’s overly complicated about simple things and dribbles casual down-and-out effrontery all over the carpet. It’s a map drawn to show someone how to keep breathing.”

“Oh yeah, like, I was having one of those days. I went to the gathering on Henry Street and met a guy named Henry who didn’t know my name, so I told him. Everyone milled about drinking and barely eating anything. Models snorting coke in the corner (I asymptotically approached). Editors telling me they meant to read that piece I wrote. An artist with a surprisingly grateful disposition. You know, a party.”

“Yes, exactly, like, I just came out this way, with too many guns in the glove compartment. I mean violent: a silver spoon in my mouth and the steering wheel of a ’67 Ford Mustang between my two chubby baby arms. Born for a road apart, a dying streak of no-good luck, sinister only-child energy, like a guy who sneers at Christmas movies then gets mad when his mom buys him the wrong kind of coffee machine.”

Angie butted in. “I thought about my Dutchess of Houston Street all day long, lost in her fragrant blond hair, her honeysuckle nose job. So gone was I that it wasn’t until I hit Seventy-second and Lex that I even realized I’d walked straight through the glass door of a CVS. Luckily I’d stopped in there to buy Band-Aids. Okay, now can you tell me one kind of story you do like? Just name one and I’ll lay a nice little stack at your . . . er . . . feet.”

“I don’t know.”

“Come on! I’ll just say it then: you enjoy those desperate little books about women who can’t make up their minds about anything.”

Jean stared at the edge of the mattress. She didn’t feel like looking Angie in the face anymore. It was true she’d read dozens of these books. And even when she went to a used-book store and picked out something on a whim, because she liked the cover or the first sentences, it usually ended up being one of those. Even when she bought a book by a man.

She’d encountered these stories so often they’d begun to feel like fairy tales about women who were girls, even when they were lousy with alcohol, sex, and loneliness. The girl who writhed in the web of her bedsheets, walked the streets trawling for impressions. Always she seemed to drag a net behind her, a beautiful net through which everything one day passed. A provisional figure. The desirable first sketch of a woman, poised like a piece of scaffolding with no distinct desires of her own.

“I mean, you have excellent taste,” continued Angie. “I love those books, too, as you know.” Jean met her eyes again and exhaled a light puff of laughter.

“Yes, but lately I just don’t know. I read them compulsively. And when I put them down I feel as if I’m more where I am than I was when I started. Perhaps I will try reading some other kind of book next.”

He felt day by day as if he were building himself a machine for endless sinking. A dreamcraft that follows blind the subterranean currents. This machine whose sole purpose was to one day touch the ocean floor, as a child suddenly finds he can grasp the higher branch of a tree, in fact never reached it. Meanwhile the sea itself seemed to deepen hopelessly, like shadows do as the day creeps onward.

Walter [the German spa worker who gives Charlie rough massages during his time on board] had remarked that he was lucky enough to have a sense of days passing at all. But Charlie couldn’t remember when he had said that, only that the room had been dim, which was meant to relax him. He realized that he’d begun to speak of “days” as a matter of habit. The sacred tradition of apportioning hours no longer applied. It was the centuries that seemed to escape him, not the hours.

The clocks needn’t tell the truth, for he knew it in his bones: These were dark times, the darkest he’d known. He’d stopped turning off his light at night.

Jean hadn’t heard Angie come in from her date with Frank but saw the door to her room pull shut. A wave of shocked sickness washed over her, as if she’d just seen the tail of a giant lizard disappear around the corner. Angie had grown unnaturally quiet, signaling to Jean that she was in one of her darker moods. Jean closed her laptop and followed.

She found Angie standing in the corner of her room, leaning against a tower of books.

“I left some pasta in the fridge for you,” said Jean.

Angie thanked her with relief in her voice but stayed rooted in the spot. Then she was suddenly kneeling on the bed with her hands in her hair. Jean could see she had begun to cry, or had ceased not-crying, as her skin already had a redness to it. She moaned that it was about Frank, who had not shown up for their date and wasn’t responding to her messages.

“It’s over,” Angie said. “This is his way of saying so.” But it didn’t seem like she believed it. In her friend’s eyes Jean could see abandonment taking on dozens of shades, tying her further to his vision, to a world colored by him. It would take a long time for this attraction to die. And then, of course, he could always come back.

“It’ll be all right,” said Jean, without much conviction.

“You don’t understand.”

“Don’t be silly.”

“No, listen. You’re a responsible person with this intense focus. You’re strong and hardworking. You don’t lose yourself in games as I do.”

“Hardly. I mean, can’t you tell what I am? If I had a free roof over my head or any unearned money, do you think I’d even have this job? I work to have one thing settled, and that’s money, but I don’t know what I want. Sometimes I think that without work I’d slide right off the face of the earth, sever all ties, absorb myself in literature, and the dwindling embers of my own personal intrigues, and the ‘personal life’ sections of Wikipedia entries, and TikTok, until there was nothing left of me. I would be like a perfectly transparent piece of glass standing treacherously at the edge of a cliff with nothing but lovely views on either side.”

“Still, I envy you,” replied Angie. “It amazes me—and, yes, maybe pains me a bit too—that you could be, at heart, this entirely self-sufficient person, at least somewhat content to live out your days alone in a room with your books and a computer. That way of life is inconceivable to me. You can’t know how much I can’t cope. I hate myself with every nerve and sometimes wonder if it’s all I have, if this exquisite pain is my only contact with life. I think to myself, What if this suffering doesn’t end until I do? and just thinking this is unbearable to me, but imagining the thought gone is worse. I hope you think I exaggerate. It would actually be a relief. Surely you’re aware, though, that I use up all my air and there is no way for me to rise above myself. My friends and family, when they think of me, are in anguish, or perhaps they’re bored. Are you bored, Jean? More pain to bludgeon me with, either way.”

“Bored is the last thing,” said Jean. “The list is long. Most of all I love you, so please don’t believe those things you say.”

Angie cried quietly with her head down. Jean thought she looked beautiful and went to sit beside her friend on the bed, locking an arm around her shoulder. Up close Jean could see that her face was covered in irregular splotches. Her neck and some of her hair was wet. Jean thought that she would not like to be seen this way. Such tears were unrefined and predictable, big sloppy movie star tears. It also made Jean feel guilty, this inability to repress her hatefulness.

“Have you noticed,” continued Angie, “how on news programs when the pundits want to be clever and cutting they say that a political opponent of theirs ‘just said the quiet part out loud’?”

“Yeah, I know. It’s a cliché.”

“And we hate clichés.”

“Well yeah that’s, like, rule number one. Don’t use them,” Jean said, reaching with her free hand to shove a cascading lock of Angie’s hair behind her ear. “And don’t be one.”

“I’m confused, though. If we’re all saying the quiet part out loud, is that then the loud part, too? Or would the loud part be all the stuff we’re not saying?”

“I think it’s the stuff we were once saying to pretend like we were well-adjusted people, without prejudice or complex or fear.”

“Could it be all the screaming people do, but only when they think nobody could possibly be listening?”

“The screaming they do in front of people, more like.”

“The member of a couple who never shuts the hell up.”

“That would be you.”

“It’s only my generosity,” protested Angie. “I give you so many chances to ridicule me, because I know it’s what you like to do.”

“I won’t argue with that.”

“No, sometimes you let me win a few rounds, too.”

“That’s me,” said Jean, snuggling into a corner of the bed, waiting for sleep to take her by the head and drag her away.

When he called her again the office was especially empty, and Jean had stopped paying attention to her work, gladly letting her thoughts wander. It was the end of March, and writers were crawling out from their hovels to take meetings in person at cafés. Even Norma Desmond would occasionally go for a walk during writing hours, which felt like real progress. They’d hired an intern to share the pit in the middle of the office with Jean, but his cat was sick, and he was working from home to take care of her.

On the phone, Jean was reticent at first, and she thought the voice could sense it. She asked it questions to further deflect from herself.

“What do you do when you’re stuck?”

“Well, nothing, obviously . . . ”

“Haha. You know what I mean. What you do to get unstuck.”

“With writing, you mean?”

“However you’d like to answer me.”

“All right, I’ll answer you like this: When I’m stuck I start paying attention to my dreams.”

“You mean you interpret them?”

“No, I never interpret, never analyze. With dreams that’s deadly. I simply write them down, read them over, and revise them. After a few days I begin to remember them more frequently, in greater detail, and I record elaborations until I hit a wall. Before long I’m dreaming in narratives rather than images. Then the narratives begin popping up in my conscious thoughts too. I’m still writing them down and reading them, like a painter going over the same part of the canvas repeatedly, creating texture, color, light, and gradually a larger picture emerges, I accept life more easily, my moods whistle by like lost steam. If it’s really going well then I am like the painting or the novel itself, which feels nothing. I have all the equilibrium of the medium.”

“I don’t remember my dreams,” said Jean, sighing.

“Perhaps you should try. They can be so compelling. The other night, for instance, I had a dream about you.”

“You did?”

“Yes, is that strange?”

“No,” said Jean softly, then, recovering a boldness in her voice, added, “Perhaps I dream about you, too, and don’t even know it. It could be that I’m a cowardly dreamer. But I’d like to hear your dream.”

“If it won’t bore you, I’ll tell you.”

“It won’t.”

“All right then. You were sitting at your desk in an office. It was just like the office you really work in, only there was more of it, more desks surrounding yours, more offices behind the glass doors on the far walls, and there were many levels. You could look down from one floor and see everyone below, like the lobby of the New York City Ballet. But you were on the lowest level, and I only focused on you.”

“You’ve been to my office before?”

“Once, many years ago. I came in disguise.”

“Was that really necessary?”

“I thought so. Nobody actually wants to see me anyway, whatever the gossips say. It would ruin their image of me, which is all that most people care about. Better for me to be a text.”

“Interesting.”

“May I go on?”

“Please.”

And so Teller did, delicately. “I couldn’t see what you were working on, only that you worked strenuously, in service to powerful interests. There were no computers in this office. Everything was done with paper, and there were reams of written documents strewn across your desk. You were only ever preoccupied with a single piece of paper at a time, but you devoted every iota of your attention to it, and it was excruciating to imagine the effort it would take for you to get through all the chaotic piles one page at a time. Slowly you turned from one paper to the next, occasionally jotting something down, immensely competent, never interrupting your focus for a moment.”

“Is that all?”

“No, there’s more. My focus on you was similarly intense, unbreakable, and as I continued to stare I noticed there were men all over the office who were staring at you, too. Beneath their gaze I noted that your clothes had become slick with sweat and your nipples had grown hard. You had been dressed modestly for work, in a knee-length cotton dress with a boat neck, but because it was sticking to you it no longer concealed your body. Still, you remained completely absorbed in your task. Men began to gather around you, some were playing with themselves, but you never looked up from your papers until finally your boss—a faceless man with a protruding belly tucked into a seedy brown suit—ordered you into his office. He said, ‘This won’t do!’ and demanded that you remove your dress. You obeyed passively, revealing that you were wearing a bra but no panties. Some of the women in the office began to congregate by the glass door of the boss’s suite. Most looked judgmental, a few desiring, as their faces pressed closer and closer to the glass. Everyone in the office had their eyes on you, including your boss, who looked perplexed, as if he’d never been faced with a situation where all of the company’s resources were being wasted at once. You, at least, needed to work, to pick up the slack. The pages of your boss’s daybook were splayed across his desk, and he barked at you to finish them off. Without so much as a nod you got on the desk, straddled the papers, and began dragging yourself across them. The papers became wet wherever you touched them. It seemed you couldn’t possibly finish them all.”

“Then what?” said Jean with a dry throat.

“There is no more. You remained there, surrounded by your colleagues, just as focused as you’d ever been.”

“I never left?”

“No, you stayed in that room all night.”

Maggie came in from lunch. Jean caught her eye and could feel herself flush. Her skin was damp and vibrated in the chilly office air.

“Gotta go, lunch is over,” said Jean, hanging up. She stared with a twisted smile at an article on her computer screen as Maggie made her way over. Maggie often passed Jean’s desk on her way to her own, only this time she stopped and beamed down at her.

“You look so happy,” said Maggie, with a winking demeanor. “May I ask who you were talking to?”

“Your sister,” said Jean.

A week later, Jean and Angie were sitting in an almost empty restaurant on the Upper West Side on a Saturday at noon. The only other customers in the huge, ornate space were a couple of spiffy tourists loudly discussing hockey.

“Why would you bring me here?” murmured Angie. “I’ve lived in this neighborhood my whole life and have never been here. I could have gone on that way until the bitter end. The color scheme is sunset over Liberace’s hot tub, and some of the light fixtures are shaped like curly fries. Are the water glasses carved from obsidian? Even sitting here at this very moment I am not sure this place exists at all.”

In truth, Jean had chosen the restaurant because it looked anonymous and dark from the outside. She admonished herself for allowing the plum-colored curtains to sucker her in. She had intuited from television shows that real adults delivered potentially hurtful or compromising information in neutral territory, like a coffee shop with a liquor license, which is kind of what she’d thought this would be. But the coffee was awful.

“What I really can’t understand though,” continued Angie, “is why you’re telling me this in broad fucking daylight, like I’m your . . . your errand . . . not even a friend, much less your closest friend, but, rather, a professional fucking obligation.”

“It doesn’t have anything to do with you,” Jean repeated stoically.

Angie’s breathing was slow and deliberate; she picked at her lip until it bled then dabbed at it unconsciously with a white cloth napkin.

“Jean, this is my family, my history, my past. If it really has nothing to do with me, why are you even telling me?”

“Because I tell you everything.”

“Nobody tells anyone everything. This is carefully selected information. You didn’t tell me you’ve been flirting with my brother-in-law at any point in the past two months, for instance. Why? Because I despise him? Because my sister’s a dolt but she’s still my sister? Where are you even meeting him?”

“At a hotel.”

Angie’s voice became louder, more frantic.

“Jean, I despise him, you know this. He takes people away from me and I’m afraid he’ll take you too. I feel like a dog waiting for his owner to come home. Anyone but him. Please don’t do it.”

“Is he taking me away from you or am I the one taking him away? You have this fantasy of him as hateful that you can’t bear to see disproven. Maybe you even secretly want him to like you. Anyway, I’m sick of talking about it.”

Angie said nothing.

“I’m sick of talking,” Jean repeated. “You don’t even have a job. In the real world you couldn’t buy groceries.”

“I know,” said Angie, slowly, like she was churning the words through a meat grinder, “that I depend on other people. That I depend on you. Don’t you depend on me?”

But Jean’s eyes had grown rigid in her skull as the chill of resolve took hold. She saw the weakness in her friend, her vulnerability unwanted and embarrassing, like a bride at a crime scene. Angie had demanded her soothing words, her counsel, her time, yet she fell apart when Jean paid attention to someone she hardly knew. Jean had no qualms about what she was doing. Any court of law would acknowledge her argument as airtight. Yet somehow it was Angie’s desperation that most incensed her. She explained in a gallant tone that she was nothing like Angie, that she enjoyed people’s company, or hated it, but she did not depend on it. Anyone who hadn’t been handed their life on a silver platter might feel the same.

It was then that a speck of substance, like iron, lodged itself in Angie’s chest and slowed her racing heart. Some time slipped by without words, just the coffee turning cold. But her body was bright and alive. The damage hardly seemed irreparable. In fact she suddenly had to suppress a laugh, one that would fill the palatial room with the playful ringing of her voice. She had a clean, melodic way of speaking and could carry a tune. She was very young and perhaps she was about to not be anymore. Contentedly she faced her serious, tormented friend, who stared back at her with the countenance of a regal portrait, impatient to be done with all this sitting around.

Angie was, too, in her way. She wanted to see what would happen next. Waking up alone in a room, perhaps far from her friend. She would reenact her nights less often, and let the days feel too long, keeping more of her vision intact for the next viewing.

She did not recognize herself in these future moments. Who imagines happiness? How was it that even now it blossomed like an exotic flower in her mouth and kept her tongue at peace?

In the evening, after they’d sat in silence and settled up, sheepishly placing a few crumpled bills on the table as if they were gold ingots, Angie returned to her parents’ apartment, Jean to their place in Brooklyn. The righteousness Jean had possessed at the restaurant was already gone. It was not only righteousness that eluded her now, but her very sense of possessiveness, which drained from her more and more by the hour. Her brain wouldn’t stop replaying their meeting, and each time Angie’s face seemed to her more exuberant.

Jean didn’t want to think of Angie at all. Even if she had deceived her, surely Angie would have done the same in her place and maybe it was even for her own good. Still, her mood continued to wane. Anxiety encroached. Jean wanted to square Angie with her thoughts, trap her within four walls and set her aside, and if that didn’t work, she would draw a line through her, toss her away. Angie was as flimsy and defenseless as a piece of paper besieged by words. How delicate a page is, how surmountable. If one went through life divinely lucid it would be easy to take any one of them in hand and shred it, or overcome it with even more words, each more masterful than the last. It was this divine state that Jean aspired to, although she felt as if she were sinking into the floor.

There is a blank page, and a page with very little written on it, most of it unreasonable, a page that would only make sense to a few people, those in the right mood to receive it. Most would say that it isn’t worth anything until it’s been ripped up or flooded with those divinely powerful words, and that it is right to be wary, even ashamed, of the emptiness. And yet there’s no advice in the world that can protect someone from this agonizing choice: destroy the pages and become one thing, hold onto them and become something else.

That night Jean was completely in thrall to her dreams, as if drugged on them.

She was in a large, dark room with high ceilings she’d never seen before but which she intuited was hers. She loved the room desperately and felt at home in it. But the room was on fire. She saw unassuming sparks burst forth hungrily into flames, showing her more of the room as they devoured it. Heartache and fear oozed through her bloodstream, but there was no way out, and it had never occurred to her to find one.

The room was filled with everything Jean loved: the people, objects, memories, emotions. As the fire raged around her she witnessed it all burn away, although not a single artifact of her life cried out to her as it died, and this tortured her beyond comprehension, yet she didn’t cry out either, or make a single sound. Finally, all that remained was the corner of a little brown blanket she often wrapped around herself as she read or wrote in her journal on the couch in Brooklyn. Angie had brought it from her parents’ place for her when she’d complained about their apartment being too cold. Sometimes a weekend afternoon would be perfect: the words in the novel she was reading felt bracingly truthful about the most wretched parts of life, like an old friend, Angie had filled the Instant Pot with a questionable stew, and the blanket absorbed all the sun as it careened through the window.

“Must this go, too?” said Jean to the darkness. “Can’t I at least keep this?” But it burned away before she’d finished speaking, so that it seemed to her the words were the last to go into the fire. And with that the fire extinguished itself, the light left, and the anguished decreation of all things subsided. But the pain didn’t burn up the way the words, the objects, or even the fire had. The pain was a certainty beyond language that her world had come to an end; no more warmth, no more memory, no more love. The pain was in her body, but it was not of her flesh, because it had a body of its own. Once all her former intimacies had vanished, it had entered her as casually as a stranger lifting the latch of a front gate. And now this pain encircled her heart as if gripping the handle of a dagger poised to murder her without leaving any outward sign of distress.