The Musée de f.p.c. All photographs from New Orleans by Isaac Diggs, January 2021, for Harper’s Magazine © The artist

Omar Casimire dreamed of a flood a year before Hurricane Katrina arrived. The day after the levies broke, as he paddled a salvaged boat through the deluge burying New Orleans East, using a broken board as an oar, the vision resurfaced as déjà vu.

With a small digital camera, he photographed the dreamscape that now appeared in the world before him: familiar street signs barely clearing unfamiliar reservoirs. He took pictures as he watched the waters rise from a room in the Super 8 Hotel on Chef Menteur Highway, east of the city’s Industrial Canal and south of Lake Pontchartrain—both breached—where he’d needed to sign a liability waiver to stay. As he told it in a poem he wrote later, “The Super 8 roof started to peel like a Plaquemines Parish orange.”

The need to preserve what he saw followed him like a phantom. He took photographs as he sought refuge in the Ernest N. Morial Convention Center—a shelter of last resort, like the infamous Superdome—where an estimated twenty-five thousand people awaited supplies and evacuation, languishing for days. He documented a baby’s first steps amid the exhausted crowd; National Guardsmen resting in wheelchairs on a nearby street, rifles between their legs.

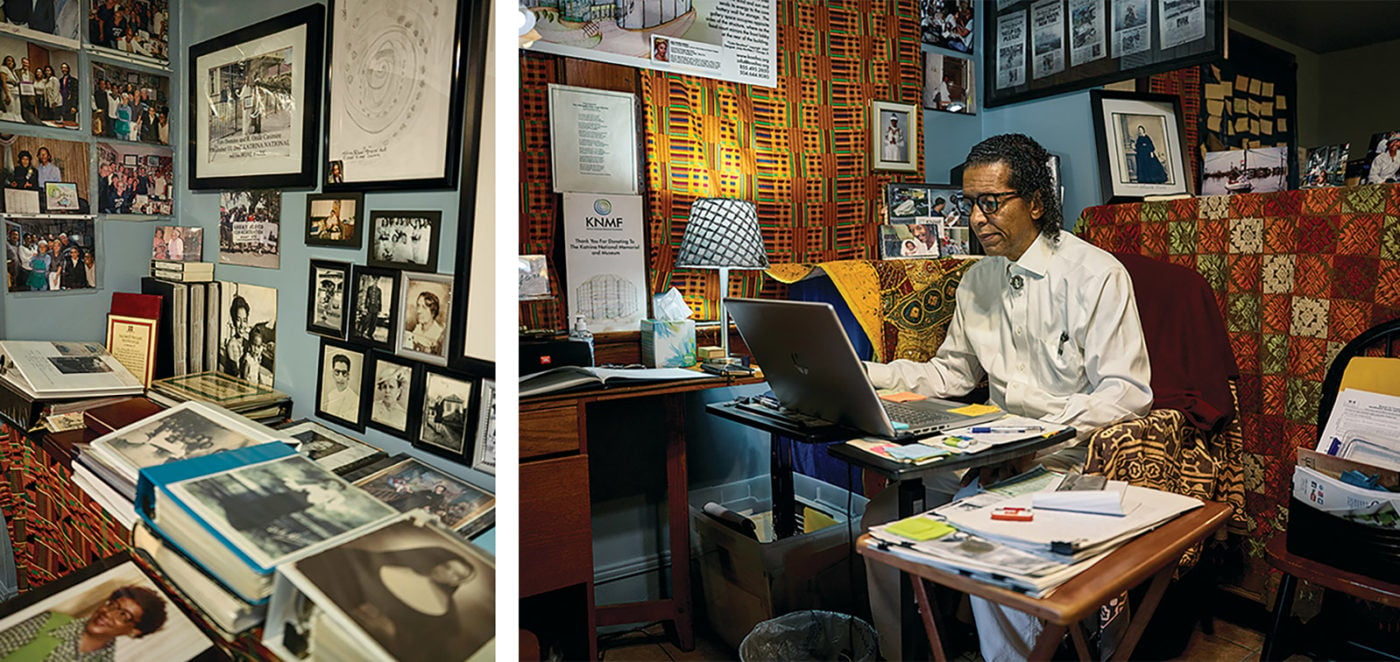

One morning in late January last year, the plastic-sheathed pages of what Omar calls his Katrina List sat in an open binder in my lap, like a holy book. It was one volume of a collection of thousands of names, phone numbers, and signatures of survivors of the storm and its aftermath. I was seated in the front room of his home on the ground floor of a two-story shotgun house on Cleveland Avenue, a notoriously flood-prone area of Mid-City that, on one rainy day in 2017, had left Omar knee-deep in water inside.

We were surrounded by a maze of folding tables, chairs, and couches draped in kente cloth. In the center of the room sat a four-by-four-foot metal cage that had been used by a search and rescue team to airlift people from the roofs of inundated houses after Katrina. Every inch of the wall space around us was occupied, covered with artwork depicting the storm’s ravages, and with Omar’s photos. On one wall hung a large tarp affixed with handwritten accounts by survivors and aid workers: Triaging a nursing home patient who handed me a wet plastic grocery store bag & said “This is everything I have left.”

Omar, a spry seventy-one, and dressed in white slacks and a white button-down, called this place the Katrina National Memorial Foundation. It was a house museum, as spaces like this are known in New Orleans—an installation of local and personal memory, sometimes art and culture, in a private home, open to the public and most often run by a black elder.

I came to the house museums through my friend Don Edwards, a gray-bearded griot who, on most days, could be found spinning tales in front of Flora café in the Marigny, where I first met him nine years ago. I lived in Louisiana as a teenager, and am now a seasonal resident of New Orleans, returning in the sweltering summers and fickle winters. Whenever I’m in town, I find Don at Flora, under the banana leaves, smoking the Pyramid cigarettes he’ll only buy at a certain liquor store in Chalmette, a suburb to the east. And he always greets me by saying, “I got someone I want you to meet.” Soon we’re on our way in his white utility van, its mysterious contents rattling and rolling in the back as we fly over potholes. It was Don who introduced me to Omar, and to many other house museum proprietors—mostly men like him: charismatic and black, over seventy, and prone to winding stories.

Each time I come back to New Orleans, I become more aware of the responsibilities of memory work. In the past two years, several of the house museum proprietors have died. I returned this time to document the house museums while they still existed, and to see the curators who remained, men who had become my friends—to listen to the stories of elders who had survived Katrina, the COVID-19 pandemic, the difficult years long before, and the precarious years in between.

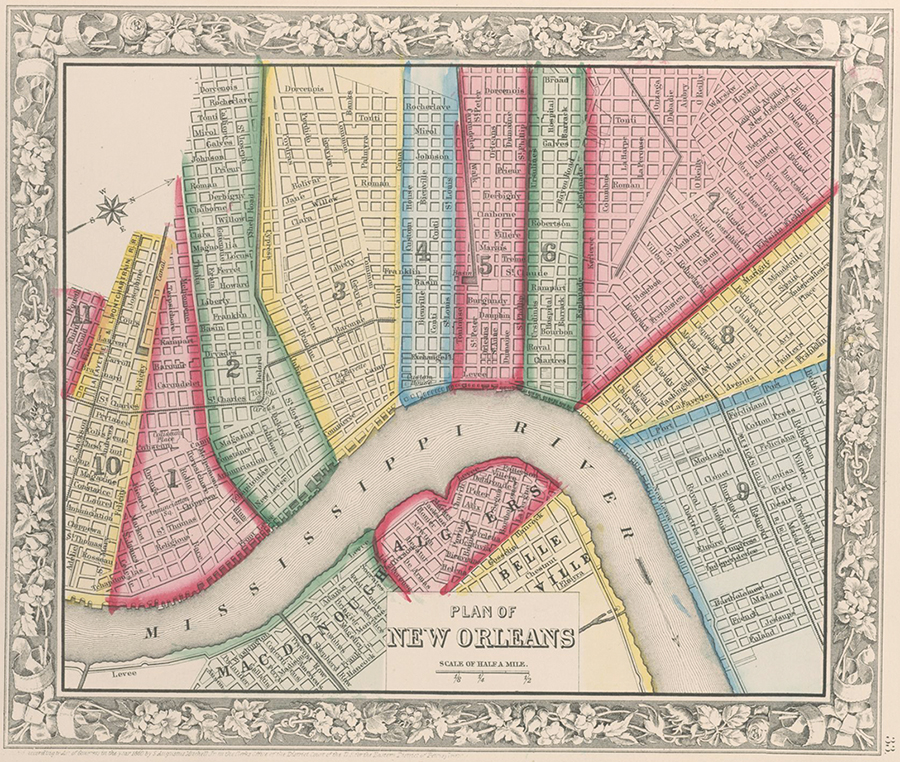

A map of New Orleans, 1863. Courtesy New York Public Library

Omar’s museum, divided from his living space by a curtain of wooden beads, is dedicated to the storm and to the dream of a future, grander memorial for its victims. Spread along one wall were blueprints, plans drawn up by his ex-wife, an architect, for the shrine of twisting glass and steel he aspires to build, its footprint the shape of a spinning hurricane. Less than two miles down the road, on Canal Street, was the city’s $1.2 million official memorial for the nearly twelve hundred Louisiana residents who died in the storm—a series of marble mausoleums containing the remains of the unknown dead, and engraved with the names of the known. “All that money, and you can barely even read the names on those big old stones,” Omar said. “And they stole my design!” The monument’s walkway resembles a cyclone from above. Omar had sent a cease and desist letter to the mayor when it was constructed in 2008—he handed me a hefty three-ring binder to show me a copy. “I call this my Blood Book,” he said. Inside were dozens of missives: sent to the IRS, and to New Orleans city planners, citing sundry broken promises, especially regarding the city’s sites of public history.

Omar flitted around the crowded room like a hummingbird, conjuring more documents and photo albums from overflowing drawers and shelves crammed with books about the storm—titles like 1 Dead in Attic, and Not Just the Levees Broke. The inauguration of Joe Biden played quietly on a television perched amid the papers on his desk. “Do you remember Barack Obama’s inauguration?” he asked wistfully. “I was there!” He’d arrived a week early and stayed in what he called his “executive suite”—a van parked at a rest stop outside of D.C. He handed me a commemorative talking pen, still in its plastic cover, that blasted a line from Obama’s 2008 election night acceptance speech: “Change has come to America!” I remembered it of course—the feeling that things would be different.

Omar told me that he’d planned to use his Katrina List to sue the government. “They abandoned us,” he said. Like many of the tens of thousands of people evacuated from New Orleans after the storm, he was flown out of state with no choice as to where he might be sent, and he arrived at Fort Chaffee, a military base in Arkansas that had housed Vietnamese refugees in the Seventies and Cuban refugees in the Eighties. “Some people don’t like to be called refugees,” he said. “But I tell them, ‘You was a refugee.’ They treated us like cattle.” He spent his days at Fort Chaffee watching news coverage of the flood and searching the internet for information on his home and his family. That was how he discovered that his mother, Louise Thecla Jones-Casimire, had died after being moved out of her nursing home, which had lost power. A colorized photograph of Louise as a young woman in the Forties sat on a table nearby, her lips and cheeks the same powder pink.

After Katrina, traumas like Omar’s became one of the most recognizable elements of New Orleans identity, alongside jazz and Bourbon Street, and the city was met with a wave of appetite for black suffering. Local tour companies, which had long offered “ghost tours” of the French Quarter and shepherded visitors around the grand homes of the Garden District, added “Katrina tours,” delivering out-of-towners to hard-hit neighborhoods to gawk at the destruction from the safety of air-conditioned buses. This hunger for devastation has remained and in part remade the city. It’s there in the shops on Decatur Street selling T-shirts that read new orleans: you have to be tough to live here over an image of the Superdome and a handgun. It’s there in the eyes of tourists when they ask what exactly happened during the flood.

That’s a question Omar never answers directly. He speaks circuitously, often recounting the history of New Orleans, its three hundred years of European, African, and Asian migration. “Napoleon needed the money,” he told me, explaining the Louisiana Purchase, “ ’cause he was fighting our grandparents in Haiti, and he didn’t know they could fight.” Omar had figured out the Caribbean origins of my last name, and determined that we were likely cousins. “You know who this is?” he asked, pointing to a pin in the top button of his shirt, a tiny photograph of a light-skinned woman with thick black hair. I recognized her as Henriette Delille, a nineteenth-century New Orleanian nun, and the first black American woman to be considered for sainthood by the Catholic Church. “That’s my great-great-great-aunt by marriage,” he said proudly, producing yet another binder, this one full of marriage licenses, death certificates, and other records printed from the Louisiana State Archives and Ancestry.com.

Omar had long sought formal recognition of his place in New Orleanian, Louisianan, and American sagas, especially through entrée into historical societies, and he pulled the Blood Book out again to show me letters documenting his battles. He’d recently proved that his seventh great-grandfather was a Frenchman who fought alongside the American colonists in the war for independence, earning Omar a place as the only black member of the New Orleans chapter of the Sons of the American Revolution. But over the past three years he’d twice been denied membership in the General Society of the War of 1812. He turned the book’s pages to certified copies of the records he’d sent the organization, substantiating that nine of his ancestors had fought in the war. He believed that the majority-white group would rather not acknowledge his heritage. “They don’t want me to join because they know I’m kin to some of them,” he said. As he waited for a response to his most recent appeal, he’d started an alternative association: the Free People of Color Battle of New Orleans War of 1812 Society. So far, he was the only member.

By the end of the visit, I was left holding everything Omar had thrust into my hands—the Katrina List, the photo albums, the Blood Book, the talking Obama pen. I didn’t want to set any of it down, for fear of implying that any piece was unimportant.

As I balanced these items in my arms, Omar led me to an altar, tucked away in a far corner of the room. On a cloth-covered table sat Hindu prayer cards, a brass bell, a peacock feather, a small bottle of Barefoot wine, and photos of spirits related and unrelated: famous yogis, an aunt who’d passed away the year before, and Omar’s youngest daughter, Asha, who’d passed in 2007 at twenty years old. “She had a weak heart,” he said. A note written just days before she died rested against her wedding portrait: I pray for health, wealth, happiness, and love now and forever for myself and the world.

The altar was like the museum—or rather, the museum like the altar. It had the same accretive logic, the same impulse to collect material shards left behind, and to say, “This was life.” Or, this is life. “What do you think?” Omar asked. “Does it need anything?”

Omar’s wandering had seemed to me a refusal of plain suffering, something akin to what Zora Neale Hurston called the African-American “will to adorn.” It was certainly a refusal of simple answers. For several decades, the house museums have shored up longtime residents’ memories and their own views of the city. For a generation of black elders, these places are an antidote to a society that has told them in no uncertain terms that their lives and deaths do not matter.

Through Don I’d met proprietors such as Charles Gillam, of the Algiers Folk Art Zone and Blues Museum, a gallery of paintings, sculptures, and quilts by local artists, and Ronald Lewis, of the House of Dance and Feathers. Lewis’s museum, like another, the Backstreet Cultural Museum, run by Sylvester Francis, was dedicated to the Mardi Gras Indians, the all-black societies known for their elaborate suits of beads and feathers. When I visited the House of Dance and Feathers in 2014, a one-room structure in Lewis’s backyard in the Lower Ninth, the walls were covered in photographs of parades, the ceiling hung with decorative fans and fragments of beaded aprons. At the Backstreet Museum a few years later, in a former funeral home in Tremé, Indian suits towered like trees forced to grow inside, their headdresses brushing the ceiling.

It was also with Don that I first visited David Fountain’s Spirit of New Orleans Museum, a sparse space in Musicians’ Village, in the Upper Ninth. Plastic-protected newspaper clippings documenting Katrina’s aftermath covered the chain-link fence along Fountain’s driveway. Among them was a photo that had spread worldwide, of a corpse lying beneath a brick-anchored sheet, spray-painted with the words here lies vera god help us. In the yard, where Fountain sat fanning himself, was an installation of what he called his “Katrinas”: a collection of mannequins in sunglasses and wigs. The contiguity of tragic and comic struck me as another type of refusal.

The intent of each house museum is not always immediately apparent. (Omar recently had a visitor who’d arrived in an Uber, drunk at midday, who looked around and declared, “This ain’t no museum! This is a house!”) The curators themselves provide the ligatures of meaning. Don and the proprietors are among those called “culture bearers” in New Orleans, a title that has always made me picture them carrying culture on their heads in clay pots the way black people of another time or place might carry water. In some ways, the proprietors are the museums.

But in the past three years, Fountain, Francis, and Lewis have all passed away. In 2020, Lewis died of COVID-19, now a common cause of death for black elders in New Orleans. Francis also died in 2020, and Fountain in early 2021. As this generation of culture bearers ages and passes on, and as storm after storm, housing prices, and gentrification—accelerated by the pandemic—push black residents out of long-standing enclaves, it’s unclear who, if anyone, will take their place.

When I arrived in January, I headed straight to Flora to find Don, who had not been replying to my texts and emails for some months. This wasn’t necessarily cause for alarm—he often struggled with technology—but I was worried. When I asked the cashier inside if she’d seen him, her face fell. Don had had a stroke. I checked in at Flora every day that week, hoping he might show.

Alvin “Al” Jackson

Alvin “Al” Jackson’s Tremé Petit Jazz Museum sits on the bottom floor of his home in a bright-blue two-story house, on a street named for a slaveholding Confederate, Governor Nicholls. Seventy-seven years old and jovial, with a panama hat perched on his fluffy white hair, Jackson welcomed me into a surprisingly formal dining space, secluded from his one-room museum by partial walls. He pulled out a chair for me at a long, lacquered table, where he’d laid out a spread of waffle cookies and fruit, a pot of dark coffee, and a freshly opened can of sweetened condensed milk, having warned me over text not to drink too much coffee before I arrived: “Tengo café bombón esperando.”

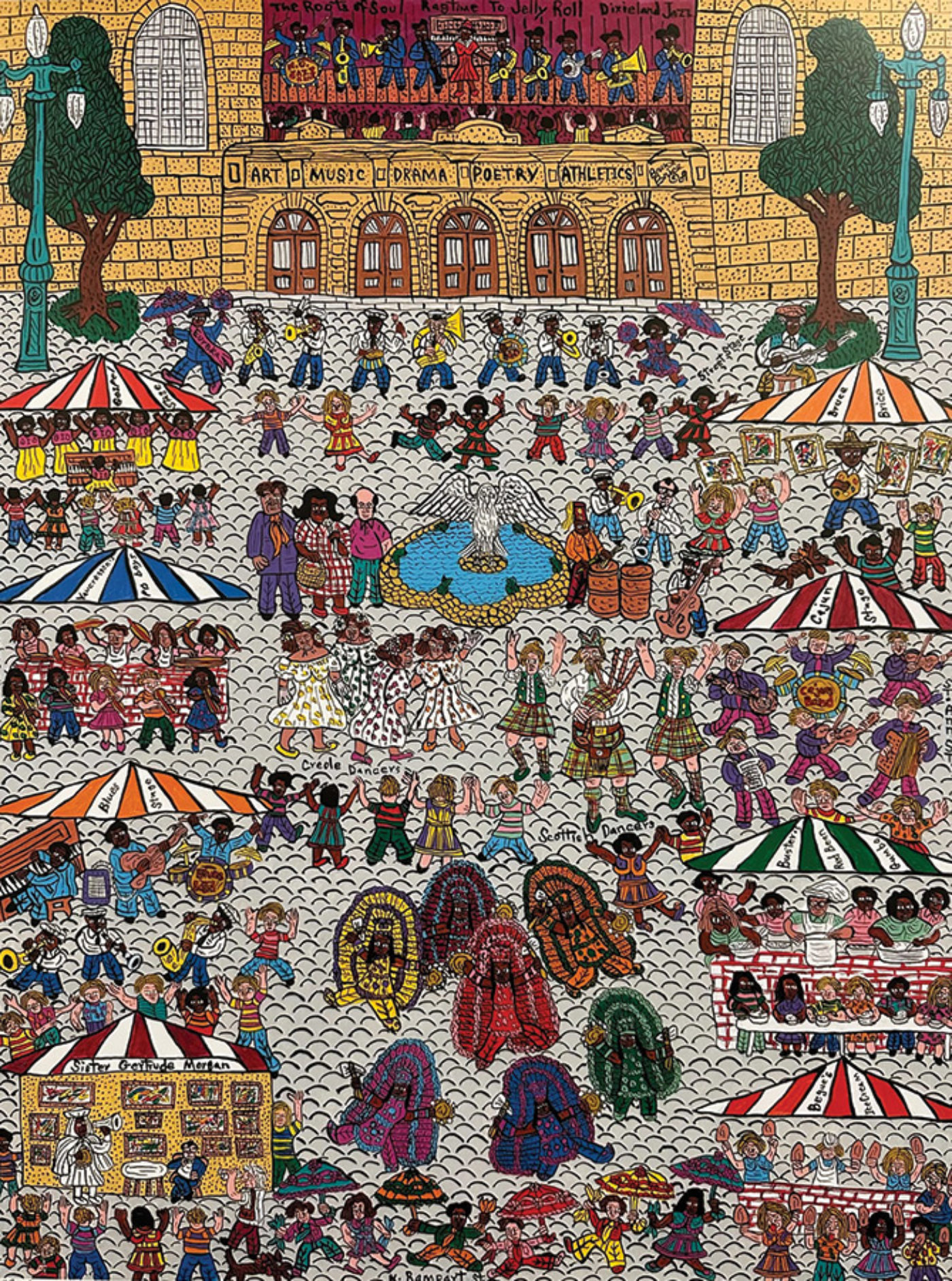

The museum was full of instruments—a piano, guitars, horns, percussion—and framed historic venue contracts: agreements drawn up for artists such as Louis Armstrong, Ray Charles, and Little Richard, for performances at classic clubs in Louisiana and Mississippi, most of which, like the famous Dew Drop Inn in Central City, no longer existed.

“It all began in Africa,” Jackson said, embarking on the story of jazz. He picked up a set of castanets. “Castanets come from the Gnawa people, out of Morocco.” He opened and closed his fingers with a clack. “Don’t let anyone tell you this is a European instrument.” He escorted me over to a painting depicting young black drum and fife players in the smoke of a nineteenth-century battle. “Does this look like a second line to you?” he asked, referring to the contemporary New Orleans brass band parades. “There’s no jazz without all-black military bands in the Civil War.” And New Orleans jazz funerals, he said, had developed out of martial funeral processions, like that which honored André Cailloux, one of the first black officers to fight for the Union.

Jackson lifted a clarinet and waved it like a wand to punctuate each stage of the instrument’s historical journey: how Emperor Maximilian of Mexico brought polka bands to Central America from Austria in the nineteenth century; how a family of New Orleans Creoles living in Mexico, the Tios, played the woodwind incorporating the Mexican style, revolutionizing its use in the United States; how Lorenzo Tio Jr. taught the New Orleanian Barney Bigard to play. It was Tio and Bigard together who wrote “Mood Indigo” for Duke Ellington.

Jackson had joined the Air Force at eighteen and was stationed in Wiesbaden, Germany. He remembered the joy of trips to multiracial Paris, “just putting on my civvies and catching the train.” When he returned home after six years abroad, he came to question the limits of what his country offered, like so many black soldiers of the time. He set out to explore the world, over the years reaching Cuba, Venezuela, Spain. In Tunisia, he traveled in the footsteps of St. Augustine, who, Jackson asserted, was black. Jackson revels in little-known and rumored African ancestries. Alexandre Dumas? Black. Alexander Pushkin? Black. Ted Cruz? “He says his ancestors are from the Canary Islands,” Jackson said, laughing. “Have you seen the Canary Islands on a map?”

He handed me a weighty document titled “After the Saga of the Confederate Monuments: Dare to Envision a Culturally Inclusive New Orleans.” It was a heavily annotated proposal he’d submitted to the city, recommending historical black alternatives for the names of streets and landmarks that still honored figures of white supremacy. The city had yet to reply. He took a book from a shelf and riffled through its pages before handing it over. On its cover was a pencil drawing of a boy in military uniform holding a drum: Jordan Bankston Noble, who’d served as a drummer in the War of 1812 as a teenager and had gone on to perform in the Second Seminole War, the Mexican-American War, and the Civil War, on both sides. As an old man, Noble had often drummed in the streets of New Orleans, accompanied by two fifers, and according to Jackson, he was the first person of color to march and play in the city’s avenues without wearing military colors. Jackson had written and self-published the book. It was carefully researched, but he took it as his prerogative to fill in gaps in the record. “People talk about historical fiction, but I prefer the term creative history,” he said. “No, I wasn’t born in 1815, and last I checked no one alive was either.”

This reminded me of a poem by the black writer Lucille Clifton, “why some people be mad at me sometimes,” and I read it to Jackson: “they ask me to remember / but they want me to remember / their memories / and i keep on remembering / mine.” The lines resonated between us for some moments, like the rings of a bell. Jackson shook his head. “We have not insisted on the inclusion of our memories,” he said. “Whether we wanted to or not, we’ve become the new storytellers.”

The next day, I walked along a strip of black-owned businesses between Broad and North Miro streets on Bayou Road in the Seventh Ward. I used to live minutes away on North Dorgenois Street, and frequented these blocks, immersing myself in what seemed to be an independent and blissful black ecosystem: King & Queen Emporium International, selling homemade incense, oils, and tubs of whipped shea butter; Club Caribbean, a dance hall behind a turquoise façade, painted with portraits of Barack Obama and Marcus Garvey in Rastafarian red, gold, and green.

I hadn’t known it at the time, but this was a type of curated experience. Much of the strip was owned by Dr. Dwight and Beverly McKenna, a local couple who intentionally rented to black businesses. I walked to meet the McKennas just a few blocks away, at one of two house museums owned by the pair, the Musée de f.p.c.—an acronym for free people of color—in an imposing Greek revival mansion on Esplanade Avenue, an oak-lined street strung with Spanish moss. The day was gray, and the grand house recessed in the shadows of hoary branches. On the wide front porch, empty rocking chairs stirred between two-story Corinthian columns. It was easy to see it as it once was: a seat of antebellum plantocracy.

I was conspicuously late and underdressed, and Kim Coleman, a thirty-one-year-old woman who serves as the museum’s director of interpretation, led me through its dim halls. Through open doorways, I caught glimpses of crystal chandeliers; polished mahogany; and oil portraits, in gilded frames, of light-skinned black people in tignons and waistcoats. The museum’s subjects were the black denizens of New Orleans who were free during French, Spanish, and American rule before the Civil War, ranging from black artisans and artists to activists such as Homer Plessy, of Plessy v. Ferguson. I’d visited the f.p.c. some years ago and knew it to be full of haunting juxtapositions. I’d held a pair of heavy shackles that had bound the legs of enslaved people, and brushed the velvet of a prayer bench knelt upon by a wealthy Creole family of the same era.

We arrived to the sunroom where the McKennas, both in burgundy sweaters, were seated with their backs to windows that faced a lush garden. Their posture was impeccable. “This is the only museum in the world that centers black freedom,” Miss Beverly said grandly. “People look at us and can’t understand why we have a black museum,” she added, unprompted. I understood: the two were so light in complexion that someone unversed in New Orleanian ideas of race might believe they were white.

“I shut that down pretty quickly,” Coleman said. “These people have lived a blacker experience than I have.” The McKennas grew up in the Forties and Fifties; Dwight in the Seventh Ward, a historical Creole stronghold. He’d had little contact with white people until his last two years of college, when he was among the first black students to integrate the University of New Orleans. “Then, you had to endure white people calling you . . . ” He paused and chose his words. “Names.” “I had a lot of animosity within me,” he said. “And I married a lady who understood.”

Miss Beverly grew up in the Midwest, in Indiana and Ohio; her debutante ball was in Chicago. “My parents were always proud of our ancestors,” she said, pointing behind me to a portrait of her great-grandmother, who was born into slavery. On her mother’s side, she could trace a line of free people of color back to the seventeenth century.

The couple had lived in Washington, D.C., during McKenna’s medical residency and were there when Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated. McKenna remembers bleeding demonstrators who were admitted to the hospital where he worked, fires that raged through black neighborhoods, and black businesses that shuttered and never reopened. “My vision, like most visions, is clouded by my experience,” he said. “My anger has not been diminished. It has been channeled.”

McKenna’s family had accrued substantial wealth over generations of liberty. The couple’s second museum, the George and Leah McKenna Museum of African-American Art, showcases works from the diaspora in a grand white home in the Garden District. They live in a third house, and own other buildings throughout the city. “We’ve had economic freedom,” McKenna said. “You cannot separate economic from political power.” When they’d arrived back in the South, the McKennas were floored by the racism of the Times-Picayune, and in 1985 they founded the New Orleans Tribune, named after the first black daily newspaper in the country.

The couple have refused the near-constant overtures of white developers who covet their increasingly valuable real estate. “The most powerful word in the world is ‘no,’ ” McKenna said. “You’re only free when you’re free to say no.” The pair’s fortune had also allowed them to celebrate the art they valued no matter the whims of large and white-dominated institutions. In 2008, their gallery was the first to acquire self-portraits by the local painter Gustave Blache III. Blache had previously met with staff from the New Orleans Museum of Art (NOMA) about the possibility of a show of his work, but they had seemed uninterested. In 2010, when the McKennas exhibited more of his paintings at the f.p.c., NOMA curators attended, and a Blache solo exhibition at NOMA was arranged soon thereafter. Blache’s work went on to be exhibited at the National Portrait Gallery and the National Museum of African American History and Culture.

“There’s been a lot of interest in black museums lately,” Miss Beverly said dryly, as the day’s faint sun left the room. “They found out we’re still alive. But why do we see money going to black exhibits within white institutions, and not to black-owned institutions?” As the city’s house museums and small galleries have struggled to stay open throughout the pandemic, NOMA has remained flush with cash, and has scheduled exhibitions by black artists like the painter Jacob Lawrence and the New Orleans photographer Selwhyn Sthaddeus “Polo Silk” Terrell. Solo shows for black artists at NOMA used to be rare—years passed between exhibitions. In June 2020, a group of former museum employees, under the name #DismantleNOMA, published an open letter accusing museum administrators and senior staff of directing racist and homophobic slurs at employees, imposing racist dress codes, and perpetuating substantial racialized pay gaps. The group also alleged bias in the museum’s collecting practices, including the tokenization and exploitation of black artists. NOMA issued a public response, apologizing to current and former employees and to the community for “any hurt we have caused,” and outlining an “agenda for change,” which included increasing the diversity of its board and its acquisitions, as well as establishing a new focus on New Orleanian artists.

Some of the house museum elders, like Omar, want the recognition that would come with the approval of a larger institution. In recent years, Omar’s Katrina museum caught the attention of professors in the museum studies graduate program at the Southern University at New Orleans, and he was invited to apply. But a college transcript was necessary for admission, and he’d had to reveal that he’d never attended. Others, like Mr. Jackson, are unbothered by their position outside the fold. Jackson described his own qualifications, saying: “It’s like having a PhD in history—I don’t, but I do.”

Fari Nzinga, an anthropologist and a co-creator of #DismantleNOMA who’d held a prestigious fellowship at NOMA from 2014 to 2016, said that the museum wasn’t unique in its culture and practices, but that it seemed extraordinary in its disregard for its community and the artistic production of black New Orleanians, on whose reputation and labor the museum depends. As for the house museums, Nzinga said it was clear that major New Orleans establishments “haven’t given two shits.” If they had, they would have supported them, sharing resources, tools, practices.

After my visit to the f.p.c., I called Kim Coleman. She and I were both young, pedigreed black professionals who had been let down by many of the institutions we were told would guarantee our happiness and financial stability. “We grew up with imminent success,” she said. “The house museum elders, they grew up with imminent failure, and yet they are optimistic. The only way they could self-validate was to name themselves what white people would never call them.” Owners, curators, historians. “At the same time,” she said, “to exist, they’ve had to do something completely different than mainstream museums: that is, develop a community.”

The elderly proprietors I know don’t have succession plans for their projects. When I asked Mr. Jackson if his daughters might take over Petit Jazz, he told me flatly, “You cannot live your dream through your kids.” Omar was evasive but the thrust of his answer was the same. “My family is interested, but they’re not interested,” he said. Coleman, who’d seemed a likely candidate to carry on the practice, planned to get out of museum work. She hoped to help the McKennas and the f.p.c. access a series of new grants and then begin her own work as a public archivist. She wanted to be in a decision-making role behind the scenes. She was exhausted by the need for in-person narrative at the small museums. Visitors, she said, especially white men, were always asking her, “Where did you learn this?,” challenging her authority. “I’m tired of telling you stories,” she said. “Why can’t I act as a gatekeeper as well?” She was uncertain the house museum tradition would carry on. The younger generations, she implied, favored less emotionally invasive culture work—they protected themselves. “But,” she said, “I hope young people won’t mind proving to elders that we are worthy of carrying the torch.”

Finally, on my last day in town, there was Don, at Flora. Except for a walker, folded discreetly beside his chair, the scene looked much the same as it had for all the years I’d known him: Don under the banana leaves, smoking his Pyramid cigarettes. “I got someone I want you to meet,” he said. But it was someone he’d introduced me to years ago. When I told him I was on my way to see Omar, he furrowed his brow and asked, “Now who’s that?” I felt the ground move beneath my feet. The two had known each other for a decade. When I gave a few identifying details—the Katrina museum, the white button-downs—Don smiled. “Oh, Omar,” he said, his face relaxing. “When you see him, tell him I say hey. Tell him I haven’t forgotten him.”

In August, I returned to New Orleans to meet Demond Melancon, a young master beadworker and the Big Chief of the Young Seminole Hunters, from the Ninth Ward. The new generations of New Orleans culture bearers are more focused on public spaces than private memorialization—groups like Take ’Em Down NOLA, which targets white supremacist monuments throughout the city, and New Orleans for Lincoln Beach, which advocates for the revitalization of a historical all-black beach in New Orleans East. But I’d heard that Melancon wanted to open a house museum.

Early on Mardi Gras morning, an Indian suit, encased in glass, had appeared on a concrete plinth in the green space at Norman C. Francis Parkway and Canal Street, in Mid-City. The slab had been bare since 2017, when Take ’Em Down NOLA and others had succeeded in removing a bronze statue of Jefferson Davis. In shades of green, the costume stood like an exotic animal on display, nine feet tall from beaded moccasins to crown of ostrich feathers. Its apron, shimmering, depicted the life of Haile Selassie, the last emperor of Ethiopia. Inside the glass enclosure, strewn along the bottom, were a dozen flyers, all reading the same thing: the people are king.

The suit had been created by Melancon, who delivered it at 3 am as light snow fell, aided by a small crew of collaborators, all disguised as construction workers in green reflective vests.

I went to meet Melancon at his apartment in the Bywater, in a renovated warehouse that provides affordable housing for artists in a now largely white neighborhood. Melancon, who is forty-two, wore thick glasses and a dense black beard. A basketball game played softly on the TV, before which two canvases were stretched. On one, curves of black beads outlined the cheeks of Breonna Taylor, who was slain by police in Louisville in 2020. When finished, a pencil sketch told me, she would wear a chaplet of flowers.

Demond was the first black masking Indian to have an overseas show of his beadwork, at the Victoria and Albert Museum in London. In October, shortly after my visit, the apron detail from his 2018 suit was auctioned at Sotheby’s for over one hundred thousand dollars. The average masker costume takes four thousand hours of work and roughly a million glass beads. Until recently, it wasn’t uncommon for maskers to spend a significant portion of their income on the costumes. “I’ve made suits and lost houses,” Melancon told me. Recently, the New Orleans Tourism and Cultural Fund had begun providing grants to subsidize the costumes, and Melancon, a member of the fund’s board, had connected community members with financing. “People think I just want to talk to the mayor,” he said. “I’m trying to get us paid while we still living.”

Melancon said he taught through his art, and he saw a house museum as a way to carry that into the future. But his apartment was barely large enough to contain even two costumes. The Selassie suit stood in a corner of the kitchen, facing the fridge, like a silent family member. Like Nzinga, Melancon believed that New Orleans’s wealthy institutions should help fund the house museums, but he wasn’t holding his breath. “I’m trying to buy myself peace,” he said. In a year, he calculated, he’d have enough money to buy a place that could serve as a home, studio, and museum. He planned to call it the Tribal Seed Museum.

From behind a rack of T-shirts, Melancon pulled the canvas for his 2023 suit. Lines of spectral pencil depicted the famous 1839 revolt aboard the slave ship Amistad. On a vessel surrounded by sea, shirtless African men wielding machetes overpowered the crew. One man gripped the ship’s wheel, his eyes fixed on some freedom just beyond the canvas.

By the end of my August trip, Omar and Don had each complained that they were unable to get in touch with the other. Don was doing better, though he could no longer drive, and I arranged to pick him up one morning and take him to Omar’s. Don was excited to show me his latest project, a box of black T-shirts bearing an original coinage: new orleans music is the new cotton. The line, diagnosing the city as a culture plantation, had been a type of signature on his text messages for a few years, punctuating the end of every exchange. He told me to be ready for his forthcoming batch of Halloween shirts, which would read visit the new orleans jazz mausoleum. “Because we’re displaying the corpse,” he said.

When we arrived at Omar’s, we found him consumed by his latest aspiration: for his Katrina memorial to be absorbed into a civil-rights museum that had been promised to the city by the developers of the River District, a thirty-nine-acre commercial project along the Mississippi. Since the multimillion-dollar deal had been finalized that March, Omar had noticed that the project’s website described the civil-rights museum as a “potential” element, and he’d grown suspicious that it wouldn’t materialize. Omar had rallied community leaders, drafting an open letter—signed by Al Jackson and Beverly McKenna, among others—to remind the developers that they’d committed to the reality of a civil-rights museum, not the possibility.

Don didn’t think much of all this. “We don’t need no civil-rights museum,” he muttered. “We need some civil rights.” “Listen!” Omar shouted. “Listen!” He began describing segregation, as if this were a point of disagreement; he talked about being the first black counselor for a local Boy Scout troop, and how the white boys had tried to convince him to drink a bottle of urine they’d said was orange juice. “Now slow down,” Don kept saying.

“Now Don, I know you’ve always been progressive,” Omar said, in a tone that suggested a minor indulgence. “But listen. In New Orleans we have this tree we call the misbelief tree, the Japanese plum. And you have to start with the fruit that’s on the lowest branch. At the top, they’ve got fruits red like fire, sweet like you wouldn’t believe. And we’ll get there, believe me. But we’ve got to get the fruit that’s on the lowest branches first.”

Don was getting agitated, and announced he needed to get his T-shirts out of my trunk. I followed him outside. He fumbled with his cigarettes. “Omar has all this hate inside him,” he said. “And I just don’t understand why he doesn’t spew it all over the people responsible, instead of worshipping them for what they have.”

Before leaving town, I took Don, Omar, and Mr. Jackson out to lunch at a restaurant of Jackson’s choosing: Landry’s Seafood House, a white-tablecloth chain with a wide view of boats bobbing on Lake Pontchartrain. “Who brought this old coot?” Jackson said, as he clasped Don’s hand. Don and Omar seemed to have cooled off, and the three men chatted over bowls of gumbo and plates of discarded shrimp tails. For a moment, it seemed that maybe this was the highest fruit atop the tree. Soon, Don and Mr. Jackson began to disagree about Louis Armstrong, something about the historical marker at his birthplace on Tulane Avenue, and Omar began talking over them, trying to turn our attention to a story about the time he’d fasted for thirty-three days in New Mexico.

Later that month, Omar’s Katrina memorial and Jackson’s Petit Jazz were badly damaged by Hurricane Ida. Omar texted me on the eve of the storm, at around 10 pm. It was the anniversary of Katrina, and he was prepared to ride it out just as he had sixteen years before. “Anniversary inside; one visitor, Omar.” He was unharmed, but shattered windows let in debris and warm, wet air, warping and wrinkling his photos. Both Omar and Mr. Jackson eventually reopened their museums, Omar’s in a new home.

Before leaving Landry’s that day in August, Don had offered Jackson a T-shirt. Jackson laughed as he unrolled it. “ ‘New Orleans Music is the New Cotton.’ Exactly,” he said. “You can work it, but you can’t own it.”