Photograph by Miska Draskoczy, from his book Gowanus Wild © The artist

When I pulled the used copy of Empire: The Life, Legend, and Madness of Howard Hughes out of its white plastic mailer it felt oddly light for a book of its girth, its center of gravity not exactly where a hardcover’s ought to be. I turned it over in my hands and opened the cover to discover that the book was hollow. Its middle had been meticulously extracted, leaving a rectangular cavity in which a previous owner had inlaid a thin cedar box. It was beautifully done—perfect corners, no sign of glue.

I’d been spending the pandemic writing a book of my own, one that required a lot of research. With most libraries and archives closed, I relied more than I’d care to admit on Amazon and other online booksellers to track down and deliver secondhand copies of unusual titles, most of which cost only a few dollars and arrived at my doorstep within a day or two.

The cedar box inside Empire was empty, but not unused. I wondered what it might have once contained—cash or pills, a sex toy, love letters, kompromat? There were faint scratches on the bottom as if it had once held something metal—keys? a knife? a gun? Does Amazon x-ray books? If there had been a gun inside, would they have found it? How long had it sat in a warehouse? And when the book was shipped, how long had it been in human hands? Eight seconds? Eleven? Two?

The walk from my home to the building where I keep a studio cuts a cross section through several strata of life in the northwestern quadrant of Brooklyn. The route begins in Boerum Hill with a buttonhook into the historical affluence of Brooklyn Heights before doubling back through Cobble Hill and Carroll Gardens. For the better part of a mile, I follow a long street lined with brownstones that become incrementally less grand on the gradual approach to the Brooklyn–Queens Expressway. Before I cross beneath the highway each morning, I stop for a coffee, a respite that marks the midpoint of the journey. The last mile of the walk traverses a distinctly different landscape.

Coffee in hand, I pass below the expressway and cross Hamilton Avenue, where traffic piles up at the entrance to the Battery Tunnel. The elevated roadway stands fifty feet above the street at this point, and on rainy days, streams of runoff spill down from the steel deck. I turn left and continue in the shadow of the highway. The sidewalk rises to meet the Hamilton Avenue Bridge (a drawbridge of the double-leaf bascule style), which crosses the greasy mouth of the Gowanus Canal, which has for more than a century functioned like the borough’s intestine, absorbing the toxins produced by chemical factories, manufactured gas plants, and tanneries.

On the seaward side of the bridge, the canal widens to meet the harbor. A dusty-blue stanchion of the Verrazzano Bridge is visible on the horizon. To the right is Red Hook and what remains of a brick warehouse, a fixture of the waterfront since 1886 that was demolished to make way for new development. On the opposite bank of the canal, barges deliver sand and gravel to an asphalt factory, and shipping containers full of compacted garbage await departure from the marine transfer station.

Beyond the bridge, the expressway lurches earthward again and veers west to follow the coastline. My studio is in one of sixty-odd buildings that sit on the marginal bit of land bounded by the canal and this crook of the expressway. When I first moved in, ten years ago, I bought a used Schwinn and biked to work exactly three times before I saw a fellow cyclist being loaded into the back of an ambulance at the end of my block. This stretch of Third Avenue, a straight shot through Industry City to Bay Ridge, is notoriously dangerous both because of the low visibility beneath the belly of the expressway and because it is so often traversed by truck drivers unfamiliar with the congested Brooklyn streets.

In the opening line of Janet Malcolm’s essay “Forty-one False Starts,” she describes the “places in New York where the city’s anarchic, unaccommodating spirit, its fundamental, irrepressible aimlessness and heedlessness have found especially firm footholds.” This is one of them. The asphalt median directly below the expressway is thick with cars stripped for parts, miniature alcohol bottles, splintered shards of fiberglass ladders, and dense carpets of guano beneath the steel girders where pigeons roost.

Any New Yorker will tell you that there was a noticeable uptick in trash during the pandemic—both because sanitation workers were justifiably upset that they had been pressed into service under perilous conditions while those of us “non-essential” workers sat at home; and, I suspect, because enough people felt that the state of the world was sufficiently abject that littering seemed like a peccadillo under the circumstances. Over the past two years, trash has amassed in atypically large drifts against New Jersey barriers or tangled in chain-link fences like tumbleweed.

Amid this accumulation there was one species of garbage, however, that asserted itself as newly ubiquitous: the sad, discarded clear plastic bottle, twelve or sixteen ounces, Poland Spring or Gatorade or AriZona, filled with various shades of foggy human urine. I counted seven on a single commute last year, and hardly a day has passed since that I have not seen at least one. They are intriguing, if revolting, objects—vials of uric amber—capable of sending the mind in several directions at once, and I have begun to hunt for them like rotten Easter eggs.

It was because of these bottles of pee that I ordered Empire, as well as several other biographies—there are many—of the famously secretive Hughes, who at one point during his unraveling, began to obsessively hoard his own urine. I couldn’t help associating the bottles along my walk with those in a scene from Martin Scorsese’s 2004 film The Aviator, in which Hughes, played by Leonardo DiCaprio, stands naked and bedraggled before a line of piss-filled milk bottles arranged on the floor like a row of jaundiced alligator teeth—symbols of his paranoid solipsism, his excruciating experience of his own body’s failure, and his desire, in the face of it all, for some vestige of control.

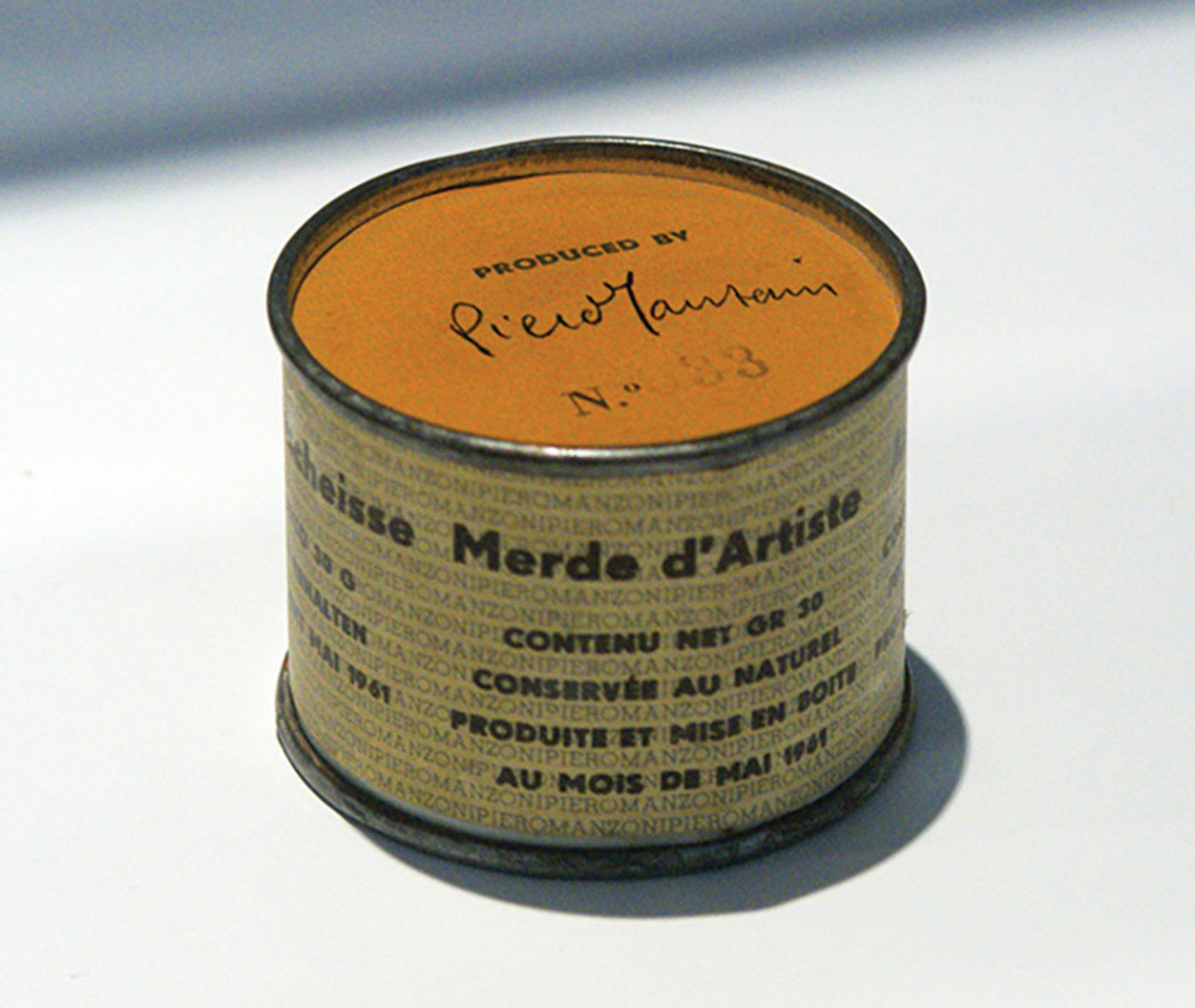

These bottles are surprisingly powerful objects, sterile in their synthetic containers but charged with a disarmingly corporeal presence. On more optimistic days, I imagine them not as testaments to madness so much as little missiles of productivity—artifacts reminiscent of the Italian conceptual artist Piero Manzoni’s 1961 Merda d’artista, a series of ninety tin cans (allegedly) filled with his own feces. Manzoni was asserting the role of the artist’s body in the process of production at a time when personality was becoming an integral component of commodities in the art world. Like Yves Klein and Marcel Duchamp, Manzoni was turning a mirror back on the art market and toying with the idea of the artist as alchemist. In a letter to the French artist Ben Vautier, Manzoni suggested that “if collectors want something intimate, really personal to the artist, there’s the artist’s own shit, that is really his.” The tins, originally valued according to their equivalent weight in gold, about thirty-seven dollars each, have since sold at auction for more than two hundred thousand dollars.

A generation later, Andy Warhol painted canvases with copper paint and invited assistants and Factory guests to piss on them while it was still wet, accelerating the oxidation of the copper and creating fluid, turbulent compositions in an ironic homage to the macho dribbles of abstract expressionists like Jackson Pollock (who himself was rumored to have pissed on paintings acquired by collectors he did not like).

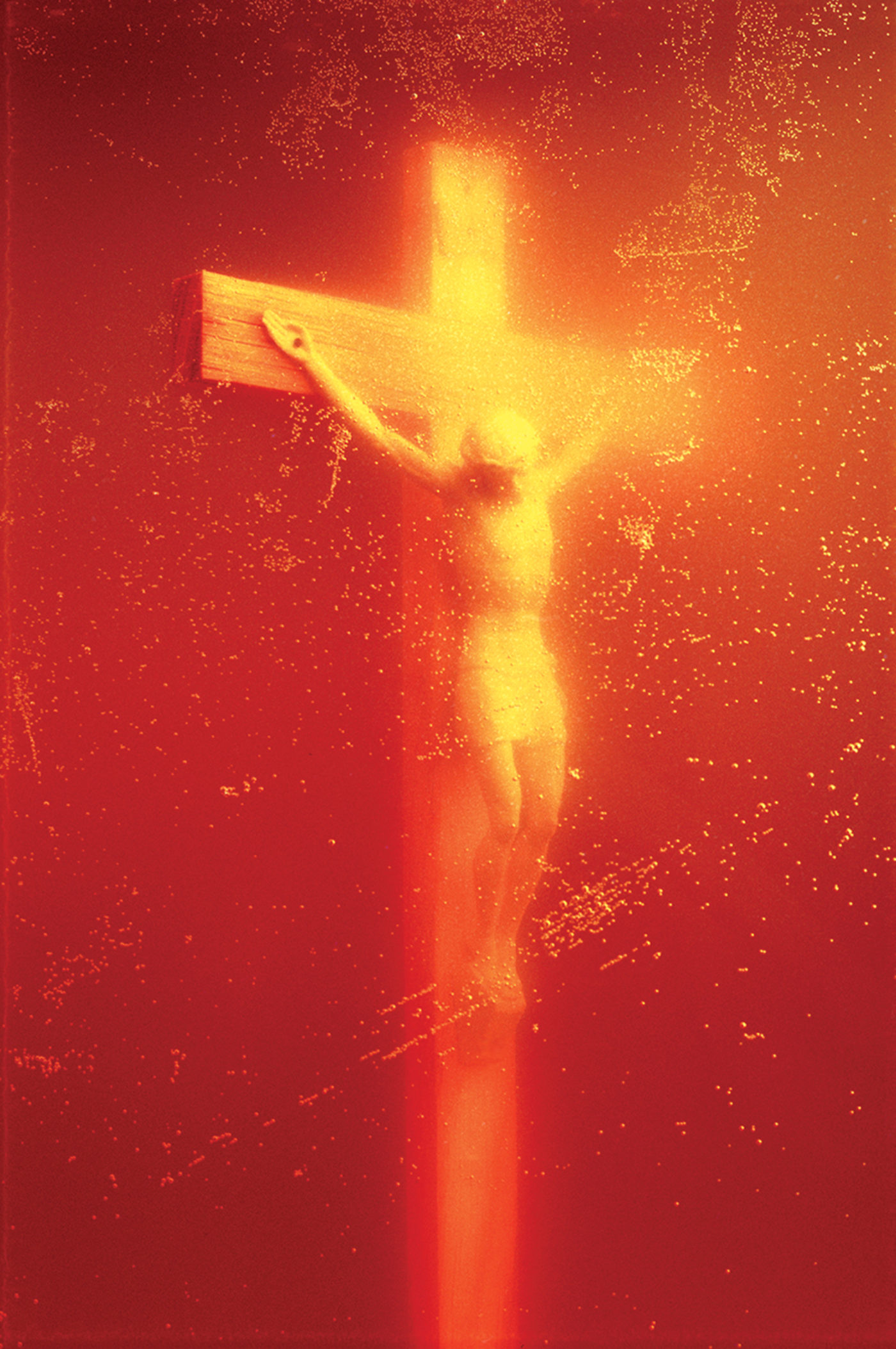

The most famous modern urinary work is certainly “Immersion (Piss Christ),” Andres Serrano’s hazy 1987 photograph of a plastic Jesus submerged in a jar of the artist’s urine. “Piss Christ” created a firestorm of controversy after the New York senator Alfonse D’Amato discovered that it would be included in a touring exhibition partially funded by the National Endowment for the Arts and tore a reproduction of the exhibition catalogue to pieces on the Senate floor. (It is perhaps noteworthy that D’Amato appeared to be considerably less upset when allegations arose years later that a tape might exist of his friend Donald Trump paying Russian prostitutes to pee on each other in a bed where the Obamas once slept.)

The “Piss Christ” debacle set the stage for the scandal surrounding the work of Robert Mapplethorpe after his touring retrospective, The Perfect Moment, also received funding from the NEA. When the exhibition opened in Ohio, a grand jury filed obscenity charges against Cincinnati’s Contemporary Arts Center and its director, Dennis Barrie. One of the seven photographs at the center of the trial was the 1977 “Jim and Tom, Sausalito,” a portrait of a man in a leather mask urinating into another man’s mouth. A second photograph from the same year (though not included in the retrospective) depicted a nude male figure kneeling over a champagne flute, cock in hand, filling the glass with a stream of clear, effervescent piss. Mapplethorpe may have been trying to challenge the conservative mores of the American public, and the posthumous ruling in his obscenity case was a milestone for advocates of free speech, but his work endures as much for the extraordinary precision of its execution as for its ability to shock.

In an excellent little book titled Pissing Figures 1280–2014, the art historian Jean-Claude Lebensztejn catalogues the history of urination in Western art, beginning with the “diuretic fantasies” of peeing Renaissance putti and progressing through works like Rembrandt’s 1631 etching Pissing Woman—referenced by both Picasso (La Pisseuse, 1965) and Marlene Dumas (Peeing with a Blue Dress on, 1996)—James Ensor’s 1887 Le Pisseur, Kiki Smith’s 1992 Pee Body, and Warhol’s line of perfume called “You’re In,” packaged in recycled Coca-Cola bottles.

One takeaway of Lebensztejn’s study is the way in which the depiction of pissing has moved from a gesture of revelry, celebration, benediction, or absolution to an act of depravity or violence. In the work of the Viennese actionists, such as Otto Muehl and Günter Brus’s 1969 performance “Piss Aktion,” urine was deployed (along with blood, semen, and other bodily fluids) with willful transgression in displays intended to break taboos and shock the audience. “The twentieth and twenty-first centuries,” Lebensztejn writes, “offer a reinvigorated and brutal vision of urination, a barrage of urinary provocations, each one more confrontational than the last, like a storm gathering strength before flattening everything in its path.”

This tendency is distinctly present in the strangely ubiquitous “peeing Calvin” meme, an adulterated likeness of the eponymous character from Bill Watterson’s comic Calvin and Hobbes peeing on any number of objects of scorn, ranging from ex-wife or a Ford logo to more politically inflected targets like pelosi or liberals. While the Calvin meme is commonly thought to have established a cultural foothold on the NASCAR circuit, Lebensztejn offers a more compelling precedent in his description of the fascist propaganda that followed the Italian invasion of Ethiopia in 1936: a depiction of a young boy pissing contemptuously on sanctions issued by the League of Nations. The characters have changed, but the vitriol endures.

In contemporary medicine, the urine sample is less charged, more sanitized and mundane, yet it is the experience through which we are all at least somewhat familiar with the uncanny feeling of watching a fluid that has been inside our body fill a plastic container we are holding, feeling the surprising heat of our interiors. In this context, as anyone who has assented to a workplace drug screening can attest, urine contains certain ignominious truths.

In 2014, to give his compatriots a leg up in the Olympics, the Russian doctor Grigory Rodchenkov engineered a plot to deceive the national antidoping laboratory. Rodchenkov’s scheme involved passing more than one hundred glass bottles of urine through a small hole in a tiled wall hidden behind a false cabinet in an Olympic collection room—an act of subterfuge staggering in both its audacity and its simplicity (forty-three Russian athletes were eventually disqualified and thirteen medals vacated). The tampered-with “tamper-proof” bottles from Sochi are a reminder of all the information these vessels might contain—little troves of forensic data. (If kept cold enough, these bottles can hold traces of DNA for weeks.)

It was common practice in seventeenth-century East Anglia to protect a person from sorcery by burying a stoneware jug or bottle filled with urine, hair, and a selection of sharp objects—bent nails, needles, thorns, or shards of glass—beneath the foundation of their home. The “witch bottle,” or bellarmine, was thought to be a powerful counter-magical device, and urine was the critical ingredient, because it was through urine that the bottle came to contain the body of its owner.

In January 2022, Christopher Key, an Alabama-based antivaxxer, sports medicine mountebank, and self-proclaimed member of the “vaccine police,” posted a video on his Telegram account urging followers to drink their own urine to fortify themselves against COVID-19. Key, who made his name selling frequency-blocking hologram stickers, jugs of negatively charged water, and deer antler spray to elite college athletes, is the kind of snake-oil salesman who thrives in moments of politically inflected medical uncertainty, but urine therapy—the consumption or application of human urine for medicinal or cosmetic purposes—has been practiced throughout the world for millennia. Documented prescriptions of urine therapy can be found in ancient Egyptian, Greek, Ayurvedic, and Chinese records. In his encyclopedic Naturalis Historia, the Roman naturalist Pliny the Elder suggests that urine might be used as a cure for gout or scorpion stings, or, when kneaded with ashes, a liniment for the bite of a mad dog.

Urine therapy was popularized in the West by the British naturopath John W. Armstrong, who claimed in his 1944 book The Water of Life that urine could cure everything from colds to cancer. Armstrong grounded his practice in a metaphorical reading of Proverbs 5:15—“Drink waters out of thine own cistern and running waters out of thine own well.” J. D. Salinger drank his own urine (as did Bret Easton Ellis’s American Psycho, Patrick Bateman), and the former Indian prime minister Morarji Desai was an outspoken advocate for the benefits of urine as a free, accessible, and inexhaustible public health resource.

But this says nothing about where all the bottles under the BQE were coming from. One clue arrived in the form of a March 2021 tweet by the Wisconsin congressman Mark Pocan questioning Amazon’s labor practices: “Paying workers $15/hr doesn’t make you a ‘progressive workplace’ when you union-bust & make workers urinate in water bottles.” In response, the company tweeted, “You don’t really believe the peeing in bottles thing, do you? If that were true, nobody would work for us.” When a deluge of anecdotal and photographic evidence emerged to support Pocan’s claim, Amazon offered a strange mea culpa: “The tweet was incorrect. It did not contemplate our large driver population and instead wrongly focused only on our fulfillment centers.”

The response reveals something about Amazon’s larger strategy of avoiding accountability by shifting responsibility onto third-party fulfillment companies contracted to complete the vaunted “last mile” of delivery. As it grows, Amazon has largely moved away from carriers like FedEx, UPS, or the United States Postal Service, preferring instead to cultivate a cheaper and more easily surveilled network of contracted delivery companies that assume enormous liability while still allowing Amazon to monitor drivers with the same elaborate tracking systems and ruthless quotas that have made their warehouses infamous.

The refrain among the thousands of drivers hired both by Amazon and by outside contractors to deliver packages from distribution hubs to homes and businesses is that the delivery quotas mandated by Amazon and enforced by proprietary software and routing algorithms simply do not allow any time for rest stops, effectively forcing workers to make other arrangements.

Amazon is the largest player in this market, but a similar quandary exists for workers across the gig economy, as demand for services like food delivery soared during a pandemic that resulted in the closure of many publicly accessible restrooms in the city. And so the lonely Uber driver, lacking a cabbie’s local savvy and social network, finds himself with no other recourse than an old Snapple bottle.

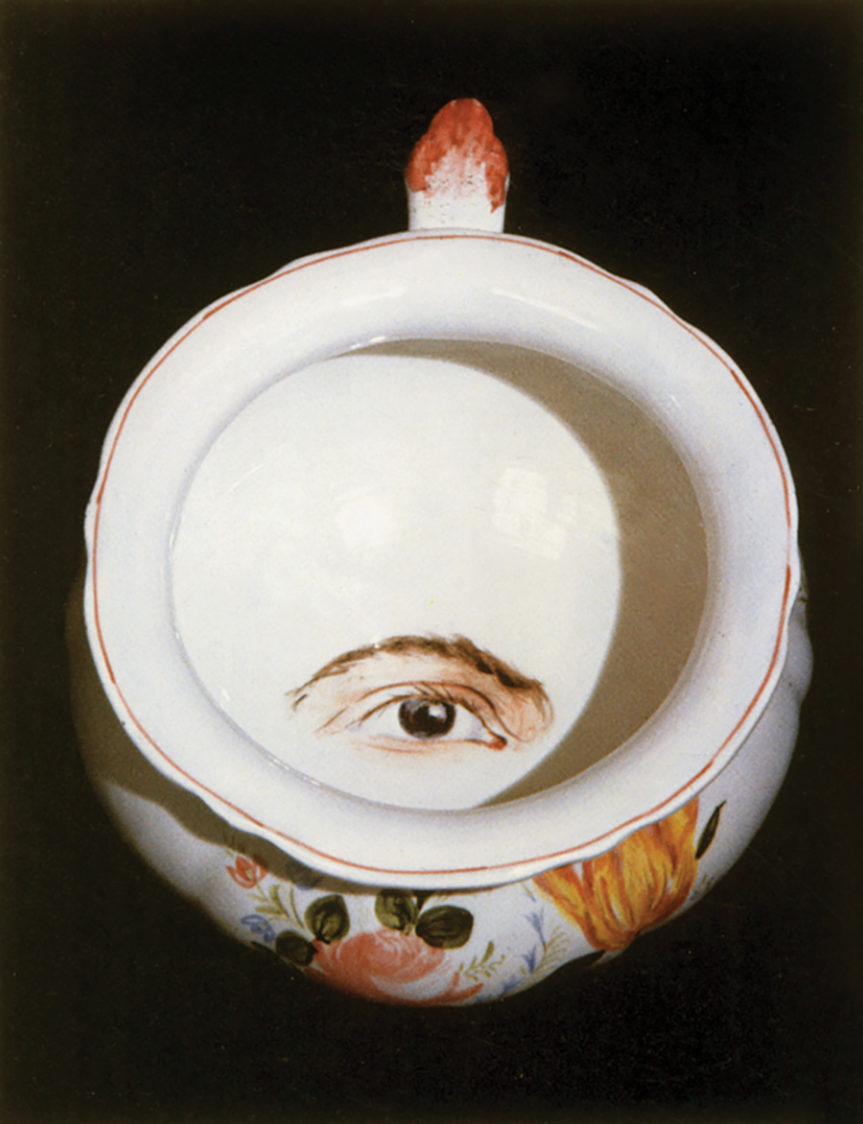

A nineteenth-century French chamber pot © PVDE/Bridgeman Images

At the height of his career, Howard Hughes was the richest man in America. He was a spectacularly successful businessman, a major government contractor, and a Hollywood mogul, but he continued to devote much of his time and fortune to his great passion, aviation. As a pilot, he set both transcontinental and air speed records. As an executive, he pushed the engineers at Hughes Aircraft Company to defy the laws of physics. His life was a perfect parable of capitalist hubris, complete with not one but two scenes of its impulsive hero crashing back to earth after pushing an aircraft beyond its limit. Eventually, the pain of those two accidents, escalating mental illness, and, perhaps, the constant scrutiny of fame led to his decompensation, and he spent his final years living in paranoid, hermetic squalor.

When he was filming Hell’s Angels, Hughes famously refused to shoot a climactic dogfight scene against a clear sky, because without clouds as a point of reference the planes would appear to move very slowly. That same cinematographic trick would have greatly enhanced the spectacle of the launch of Amazon founder Jeff Bezos’s New Shepard spacecraft in July 2021. Instead, the small ship, the pride of a new era’s sometimes richest man, seemed to cross the nation’s television screens like a cartoon dildo inching across a clear blue sky.

As I watched Bezos launch himself into space, I could not help but draw comparisons between the two men, opposite in stature yet so similar in other ways. Hughes had RKO and Bezos has Amazon Studios; Hughes had TWA and the “Spruce Goose” and Bezos has Blue Origin and New Shepard. Hughes Aircraft built planes for the Department of Defense and Amazon Web Services designs technology for the CIA, and despite these government entanglements, both men share a penchant for tax avoidance and a contempt for antitrust law (an entitled avarice that extends into the sphere of philanthropy, where both men seem less preoccupied by any conventional sense of the public good than a desire to bestow upon the world the many benefits of their own ingenuity). Here were men who embodied a distorted hyperbole of the American dream, a boyish desire to possess more wealth than anyone else on earth, and then devoted their lives to building machines to fly around it.

A teenage version of myself might have known what to put inside the hollow book—a butterfly knife or a sleeve of rolling papers—but my life at the moment is largely devoid of contraband. I tried my phone, the object that often feels like the most destructive device I own, but it was just slightly too long to fit, so I removed it and sent a picture of the box to a friend. He replied immediately with a story about the Venetian Doge Francesco Morosini, who carried a pistol concealed within a Bible, a silk ribbon tied around the trigger so the gun could be fired by pulling gently on what appeared to be a bookmark.

This potential for misdirection has made the hollow book a cinematic trope. As a filmic device, it allows for a visual miscue or a moment of dramatic irony, like the nail file hidden in the spine of a Bible in Escape from Alcatraz or the rock hammer nestled between the cut-out pages of Exodus in The Shawshank Redemption. The book safe can also deliver an extratextual reference in the form of an object literally enveloped in text (albeit an unreadable one), as with the cache of minidiscs and cash concealed within a copy of Baudrillard’s Simulacra and Simulation in The Matrix.

Perhaps it is fitting that a book about Hughes, the elusive subject of so many speculative biographies, might contain nothing at all—a text without content. It occurred to me that what I liked most about the book was not how it might be used, but the fact that such an extraordinarily personal object, so thoughtfully rendered, so gently crafted, had maneuvered through such a vast and impersonal system of distribution—a minuscule act of disruption, like a slug in a parking meter, a decoy living happily among ducks.

Whatever I do is in vain. I piss at the moon, by Pieter Bruegel the Elder. Courtesy the Collection of Museum Mayer van den Bergh, Antwerp, Belgium © Fine Art Images/Heritage Images/Alamy

Last fall, someone started systematically tearing down old brick warehouses on my dead-end block. The demolitions were seismic—rattling the walls of my building, sending flurries of dust down from between the floorboards above. One afternoon, I ate lunch on the fire escape and watched the bucket of a backhoe claw at a beautiful old wood span roof like a prehistoric sloth. Within a matter of weeks, my building, which had long stood to the lee of prevailing winds, was now buffeted by gusts blowing in off the harbor.

It was Ivan, the superintendent, a young Russian who had slowly warmed to me over nearly a decade of sharing the freight elevator, who told me what was going on. Nearly half of the block had been sold to a single development company. A total of thirty buildings, spanning three city blocks and eighteen acres, were slated for demolition. In their place, the developer plans to build a 1.3-million-square-foot “last-mile” distribution hub with a four-story warehouse so massive, so intricately ramped and cross-decked, that full tractor trailers can drive onto the upper floors and unload directly into the more agile (and less regulated) Sprinter vans that deliver packages on the final stage of their journey. It will be the largest multistory distribution center of its kind in the country.

As a boy obsessed with astronauts, I was particularly fascinated by the mechanics of peeing in space—the funnels and vacuum hoses, the lack of privacy, and the promise of electro-purification systems that would make space inhabitable by rendering water from waste. If you google “piss bottle,” you’ll find a selection of portable urinals offered on Amazon’s website that vary in complexity from something akin to a long-haul trucker’s recycled milk jug to a contraption resembling a canteen connected to a snorkel. The variety is remarkable—Amazon, the great purveyor of modern amenities, offers solutions even to problems of its own creation, making it easy for any driver to pee like an astronaut in the back of his Sprinter van without having to go off schedule.

While it may pale in comparison to the historical indignities suffered by generations of American laborers in coal mines or cotton fields or steel mills, there is something unsettling about the thought of a twenty-first-century economic imperative that forces workers to pee in plastic bottles (to say nothing of that fact that it may also be tantamount to gender discrimination). There is a pathos to this image of a body hunching awkwardly around a steering wheel or squatting surreptitiously in the dark recesses of a delivery van. It seems particularly grievous given that it is an indignity endured not in order to extract the steel to build bridges or to quarry the stone to build great museums, but simply to fulfill our desire to get exactly what we want exactly when we want it. It is, in other words, an indignity suffered in the name of convenience.

I succumb to the temptation of same-day fulfillment at times myself, but in a city where you can get anything—certainly any book—there is something profoundly lonely about the thought of ordering a novel on Amazon that is likely sitting on a shelf at a bookstore just blocks from your couch. And yet we continue to order them, even when we know this comes at a cost to the environment, the culture of the city, and perhaps even our own well-being.

To pee in a bottle and leave it on a public street is a deeply antisocial act. As the bottle of pee becomes a familiar fixture in the landscape of urban detritus, it can begin to feel like a symptom of a larger turn inward and, by extension, of a troubling indifference to the city as a communal space—not on the part of the driver who leaves it behind, but of the larger mechanism that does not allow for an alternative. Plumbing and urban life are inextricably linked. What are we to make of a civilization willing to eschew its own social codes on public hygiene for the sake of customer satisfaction? In his 1898 essay “Plumbers,” Adolf Loos writes that “without the plumber the nineteenth century just would not exist.” How do we measure the progress of twenty-first-century technology on a planet where, according to UNICEF, more people have access to mobile phones than to adequate sanitation?

Boyfriend_23.JPEG, by Shahryar Nashat © The artist. Courtesy the artist and Gladstone Gallery, New York City

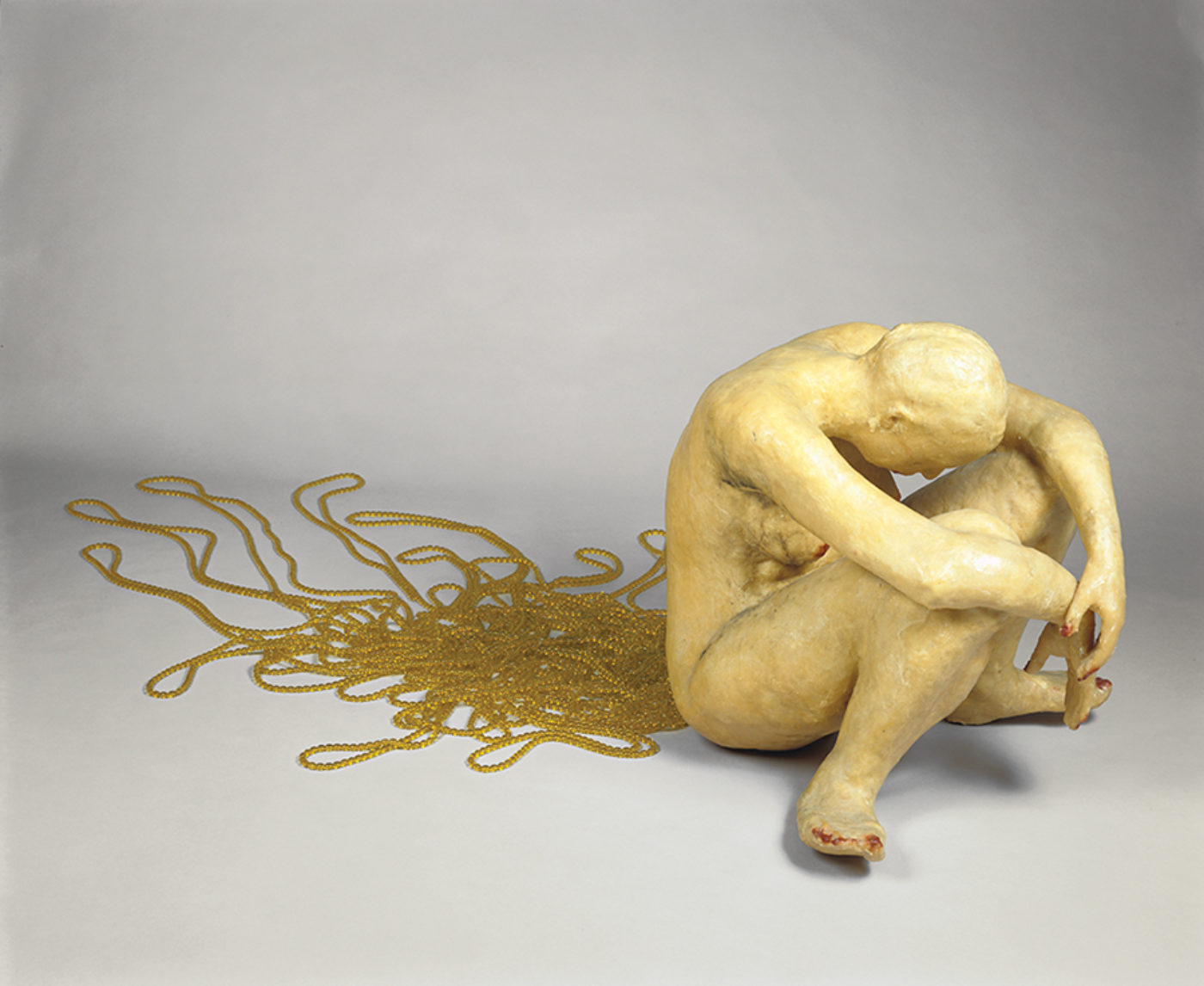

Last spring, I went to see Shahryar Nashat’s exhibition Hounds of Love at Gladstone Gallery in Chelsea. The show included a sculpture titled Boyfriend_23.JPEG, made of eight vinyl bags filled with urine (both Nashat’s and that of his partner and longtime collaborator, the artist Adam Linder) resting on two slabs of yellow polyurethane foam. The bags sag together like recumbent bodies on a mattress, sacs of fluid awash in soft pink light.

I first saw Nashat’s urine works two years ago in Los Angeles, in the exhibition They Come to Touch, which was organized by Aram Moshayedi in a derelict Hollywood office suite designed by the Viennese architect Rudolph Schindler. Schindler was a pioneer of health-conscious Californian design, but decades of negligent retail clients had left the space dreary and decrepit. Los Angeles had been under lockdown for more than a year when the show opened, and Nashat had conceived of the works as surrogates for bodies—a corporeal presence in a largely depopulated exhibition space, like witch bottles marking the corners of rooms. The bags felt more anxious then, less comfortable in their vinyl skin. They seemed to speak more directly to a period of prolonged isolation—the way in which we might all have felt a bit like Hughes barricaded in the screening room during the darkest days of quarantine. But the newer version has a presence that is less abject than it is intimate. Nashat’s bags are tender objects—watery pillows slumping into the foam, a spectrum of different yellows, like bodies both satisfied and longing for something unknown.

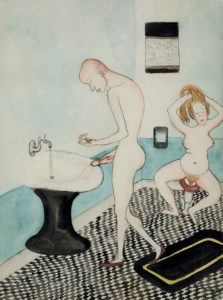

Untitled (Alice Neel and John Rothschild in the Bathroom), by Alice Neel © The Estate of Alice Neel. Courtesy David Zwirner, New York City

Nashat’s installation reminded me, in its way, of Alice Neel’s languid 1935 watercolor Untitled (Alice Neel and John Rothschild in the Bathroom), which has been shown twice in New York in the past four years (first at David Zwirner in 2019 and again in Neel’s 2021 retrospective at the Metropolitan Museum of Art). The small painting shows the two lovers, their naked bodies rosy and tumescent, peeing in unison, in the toilet and the sink. The word most often used to describe Neel’s nudes is “frank,” but there is extraordinary warmth here too. The couple seem entirely present in that moment of intimacy, so comfortable in their own bodies, so trusting, so assured of their mutual fulfillment.

I signed my name in the Gladstone Gallery guest book and walked out into the bright April morning. New York was waking up from another pandemic winter, the pin oaks on Twenty-fourth Street were filling out and a steady stream of pedestrians walked among the tall grass on the High Line above. There was life in the city again, daffodils and hot dog vendors, and in the street in front of me, between the granite curb and the tire of a black town car, sat a twenty-four-ounce coffee cup filled to its brim with piss.