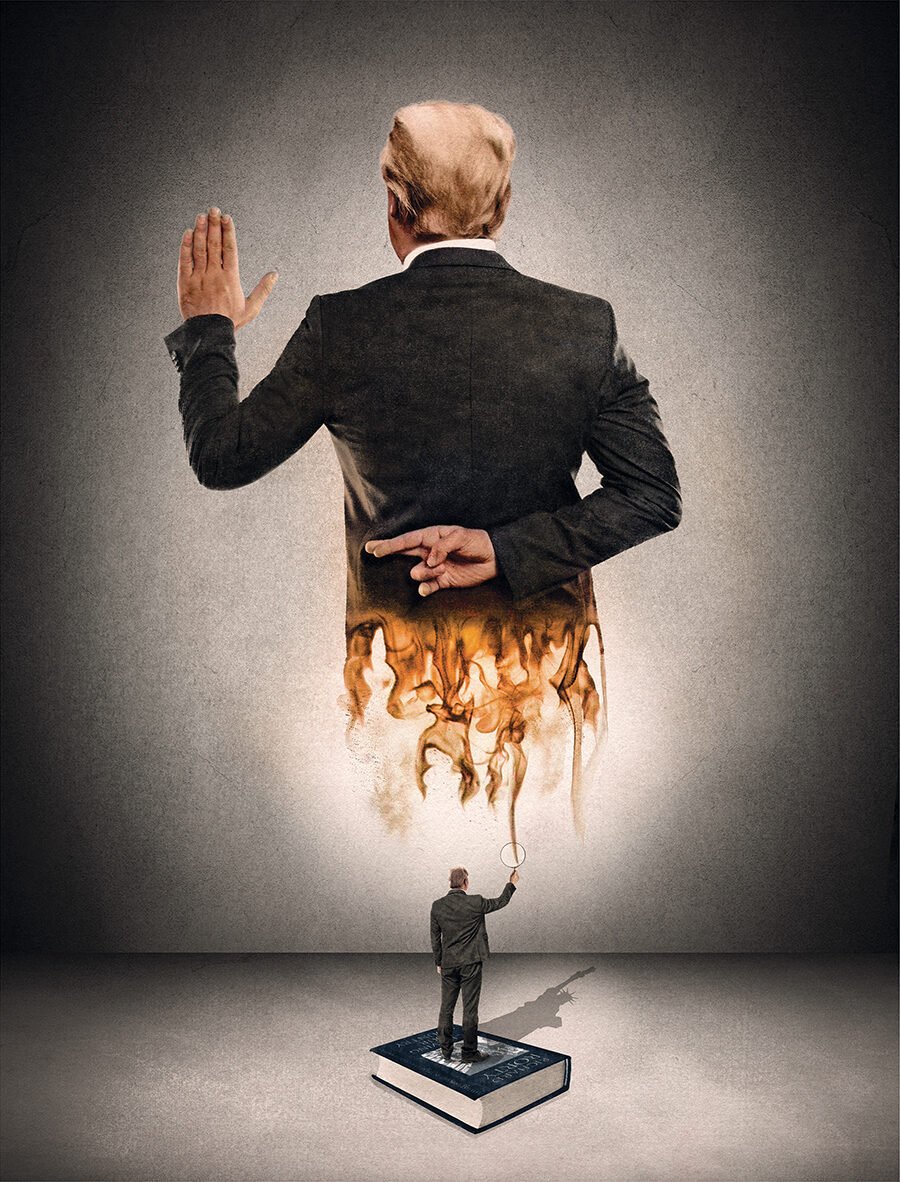

Illustration by Zach Meyer

Twenty-five years ago, the philosopher Richard Rorty accomplished something many writers aspire to but few ever pull off: he predicted the future. Toward the end of his 1998 book Achieving Our Country, Rorty considered the possibility that “the old industrialized democracies are heading into a Weimar-like period, one in which populist movements are likely to overturn constitutional governments.” He went on to describe how such a process might transpire in the United States, where

members of labor unions, and unorganized unskilled workers, will sooner or later realize that their government is not even trying to prevent wages from sinking or to prevent jobs from being exported. Around the same time, they will realize that suburban white-collar workers—themselves desperately afraid of being downsized—are not going to let themselves be taxed to provide social benefits for anyone else.

At that point, something will crack. The non-suburban electorate will decide that the system has failed and start looking around for a strongman to vote for—someone willing to assure them that, once he is elected, the smug bureaucrats, tricky lawyers, overpaid bond salesmen, and post-modern professors will no longer be calling the shots.

Rorty also described a cultural shift that might accompany this change:

One thing that is very likely to happen is that the gains made in the past forty years by black and brown Americans, and by homosexuals, will be wiped out. Jocular contempt for women will come back into fashion . . . All the resentment which badly educated Americans feel about having their manners dictated to them by college graduates will find an outlet.

After Donald Trump was elected president in 2016, Rorty’s prophecy spread, and sales of Achieving Our Country surged. Rorty—who died in 2007—had been a major figure in American academia for most of his adult life, but his posthumous fame reached new levels as millions of people who had never before heard of him read these words. I watched this development with particular interest. As it happens, I’ve probably never been as close to the writing of someone else’s book as I was to the writing of Achieving Our Country. Rorty and I were professors at the University of Virginia when he was working on it. We taught classes together; our families socialized together. Rorty was more than two decades my senior and highly accomplished, one of the stars in the academic firmament. I have had many remarkable teachers and colleagues in my career, but no one taught me as much as Dick did. I read the manuscript of Achieving Our Country a couple of times while he developed it, and twice more after it came out. When I first encountered the passage about the strongman, I had to admire Dick’s guts. (In academic writing, predictions are about as common as exclamation points.) Still, I said to myself, and later to Dick: “It can’t happen here.” Dick simply shrugged—he was a world-class shrugger—and said, “We’ll see. We’ll see.”

So I was glad when this work found new readers, even as I was dismayed by the political developments that had attracted them. Yet I could also see from my particular vantage something Rorty himself did not predict, something most of his audience could not have known: that America’s would-be strongman was a manifestation of the very philosophical tradition that Rorty spent his life endorsing.

Before going any further, I want to say that it would be difficult to imagine two men less alike than Donald Trump and Richard Rorty. Dick was the archetypal rumpled professor: the shoulders of his well-worn jacket often dusted with dandruff, his tie slightly askew. He had a red map-of-Ireland face and a loose shock of full-moon-white hair. Harold Bloom, who deeply admired Dick, told me he was “socially rather hangdog, but brilliant and kind too.” Dick could be extremely shy, at least until he got going (half a glass of wine or a full lecture hall helped), and then his powers of articulation were close to astonishing. He seemed to my younger self a version of what Wallace Stevens called “the impossible possible philosophers’ man, / The man who has had the time to think enough.” At UVA he was regarded with both respect and affection, a phenomenon probably even more uncommon in academia than in other zones of professional life. He was also a committed leftist, a child of Trotskyists, and a lifelong champion of the progressivism of his Depression-era upbringing. But none of that changes the fact that Rorty dedicated his life to advancing a view of truth—philosophical pragmatism—that helped lead Donald Trump to the White House.

Though it is generally viewed as America’s great contribution to Western philosophy, pragmatism isn’t a philosophy per se—if by a philosophy one means a particular view of reality that a given philosopher or school of philosophy endorses. It is better understood as an approach to the world. At its heart is a conception of truth put forward by the nineteenth-century polymath Charles Sanders Peirce. Peirce studied chemistry and worked as a government land surveyor, and his philosophical views were deeply indebted to the scientific method. Essentially, Peirce argued that the meaning of any statement lay in its predictive value—that is to say, in its practical consequences. To describe an element as highly flammable, for example, was not to attribute to it some metaphysical quality, but simply to say what would happen if one applied a flame to it.

Many strong minds have revered Peirce—Cornel West has said that his achievement in philosophy is comparable to Melville’s in literature—yet he is perhaps the most obscure consequential thinker America has produced, and his views have survived mostly in the reworked interpretation of his near-contemporary William James. Peirce was something of a porcupine; James was one of the smoothest, most charming people ever to stroll into a lecture hall. Known for his kindness and modesty, he was one of the few Harvard professors of the time whom students could approach without exaggerated deference. Even the discerning and particular Gertrude Stein liked him.*

James admired clarity, precision, and usable truths. To the pragmatist—James hijacked the term from Peirce, who henceforth called his own brand of thinking “pragmaticism”—truth is not a static correspondence of idea to reality. “Truth in our ideas,” James wrote, “means their power to ‘work.’ ” By “work,” James meant that a truth could be successfully put into action to achieve desired ends.

Admittedly, it is not enough for truth to be productive in this way; it must also hang together reasonably well with other beliefs that you take to be true: “A new opinion counts as ‘true’ just in proportion as it gratifies the individual’s desire to assimilate the novel in his experience to his beliefs in stock.”

As for the ends that truth helps you to pursue: those are up to you. One can be a pragmatist and a saint, using the power of one’s particular truths to bring comfort to the afflicted. But one can likewise be a pragmatist and a sinner. Mussolini had an abiding affection for James’s work. Of course, it’s not fair to judge thinkers by the quality of their epigones: Hitler loved Schopenhauer while radically misunderstanding him. But it was not necessary for Mussolini to misunderstand James.

At its best, pragmatic practice is forward-looking, optimistic, and labor-intensive. What a pragmatist achieves should never be an end in itself, James insisted, but rather an inspiration for more work. To James (and to Rorty), we are best off when we see our lives as open-ended projects that prioritize process over arrival. But as a philosophical tradition, pragmatism makes no normative claims about what is worth doing and what is not, what is desirable and what is to be abjured. Bloom and West both correctly identify one root of pragmatism in Ralph Waldo Emerson, and in particular those of his passages—there are plenty of them—that affirm power without worrying about what sort of power is in question. In “Circles,” an essay Rorty particularly admired, Emerson talks about how a potent mind can expand until it achieves power not only over itself but over aspects of the world:

The extent to which the generation of circles, wheel without wheel, will go, depends upon the force or truth of the individual soul. For it is the inert effort of each thought, having formed itself into a circular wave of circumstance,—as, for instance, an empire, rules of an art, a local usage, a religious rite,—to heap itself on that ridge, and to solidify and hem in the life.

The inspired mind creates local customs, works of art, religious rituals—and also empires. About the creation of such empires, Emerson is not apologetic. It is an amoral passage that helps give rise to an amoral movement.

But in my view, pragmatism is not the invention of Emerson or Peirce or James. It is rather the crystallization of long-standing tendencies in American culture. Pragmatism begins on the streets and exchanges, and is later articulated in the halls of academe. Its practitioners love talking about the “marketplace of ideas”—a phrase adapted from the pragmatist jurist Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr., and not one you’re likely to hear spoken approvingly by a Kantian or a Hegelian. Pragmatism guides the way many, if not most, Americans conduct their daily lives: with an eye to work, success, profit, achievement, innovation, and ongoing expansion. When William James talks about the “cash-value” of ideas (again, something it’s hard to imagine a significant European philosopher doing), he’s scooping up a sentiment from quotidian American life. What’s this idea worth? What can it do for me?

Asked to summarize his contribution to the philosophical tradition, Rorty, always modest, said that he brought the pragmatist view from an emphasis on action to an emphasis on language. Rorty argued that it was only statements about reality, not reality as such, that could be described as true or false. Thus claims about truth have always been claims about language. (Rorty begins his influential book Contingency, Irony, and Solidarity by affirming that truth is “made rather than found.”) Where the Platonic tradition strives to transcend the particulars of individual perspectives to arrive at a singular and universal truth, Rorty believed in competing interpretations. He delighted in redescription rather than logical analysis. For a culture to thrive, it needed to generate many ways of looking at the world, many strategies for solving problems, many perspectives. For that reason, poetic imagination—which offered one’s idiosyncratic views on life—was more powerful than philosophy. Pragmatists do believe in the external world, despite their critics’ carping, but pragmatists who operate in Rorty’s mode don’t consider it the task of language to render that external reality accurately. They try instead to use words to “enlarge and strengthen themselves,” and to get things done. I am not saying that the pragmatic conception of truth and language, with all its dangers and promise, trickled slowly through the culture from the University of Virginia’s South Lawn. The pragmatic relationship to words is as much sewn into American life as is the pragmatic sense of ideas and actions.

Rorty described this relationship in sophisticated and appealing ways, and was himself a man of the highest ethical principles who would never use what he believed about language to do harm. But not everyone is as ethical as Richard Rorty. When I hear talk about my narrative and yours; when I hear talk about my truth and yours, I can’t help but think of Rorty. When I hear that politics is about conflicting stories, with the assumption that there are no determinate facts that make one story better than the rest, I think of this most humane soul. When I hear politicians twist words to get what they want, with no particular commitment to truth, I cannot help but remember the vision that Rorty developed around a dingy Wilson Hall seminar table.

In a lecture I watched him deliver around the time Achieving Our Country was published, Rorty answered a question about pragmatism by saying, “Perhaps we should simply pretend that Truth has gone on vacation for a while.” Rorty was aware that he was sometimes accused of saying things to “get a gasp.” The audience did gasp—and laughed nervously. What Rorty meant was that we should give up on the quest to find some capital-T Truth about human experience that would be absolute and binding for all time. Instead, we should seek provisional truths that help us better lead our lives. And when these truths fail to put us in an agreeable and productive relation to the world, we should jettison them and search for new ones.

It’s important to distinguish pragmatism from the various forms of postmodern thinking that were so trendy in Rorty’s day. In many ways, his affirmation of pragmatic, small-t truth was a reaction to Jacques Derrida’s brand of deconstruction. I recall Rorty coming into a seminar we were teaching on literary theory with a grin on his face. He’d gotten it, he told me. He’d come up with a compressed way to explain what Derrida was up to. Derrida’s work, he said, could be seen as a polemic against closure. Derrida never wanted to stop interpreting: he would compound one association after the other, unceasingly, relentlessly. If you never stop interpreting, then there is “nothing outside of the text.” Why should artificial boundaries stop us from continuing to interpret? A book only appears to end on its final page: there are other books and other thoughts that it suggests, creating an endless web. So why stop reading and construing?

Rorty had an implicit answer to this question. You stop interpreting for pragmatic reasons—only once you think you have arrived at a truth you can put to work in the world. If you can’t apply it successfully, you resume your interpretation, but always with an eye to finding a truth that you can use.

For Rorty there was a clear political implication to the pragmatic view of language. “Competition for political leadership is in part a competition between differing stories about a nation’s self-identity,” he writes in Achieving Our Country. This is an idea that Barack Obama—one of the few contemporary politicians one could imagine being familiar with Rorty’s work—understood well. Obama told a story about American history in which his election was a culmination of imperfectly realized ideals that had been guiding America since its founding. Donald Trump—in a much more instinctual way—likewise understood this idea, and it is no accident that his political career began with the birther movement. He was telling a competing story about what it meant for a black man named Barack Hussein Obama to be elected president. In the political and cultural world we have inhabited ever since, Truth has most certainly gone on vacation.

It has been said many times that Trump was—in his own bizarre fashion—a postmodernist president. Those who say this generally use the term “postmodern” loosely. They mean that Trump cared nothing for tradition, had no regard for truth, that he lied all the time. But Trump is far better understood as our first pragmatist president. Trump knew—and knows—that Truth has gone on vacation; his acolytes know it, too. They are not nihilists, as they are often labeled, for they clearly do value something. And they are not deconstructionists, for they are prepared to latch onto pragmatic truths that will get them what they want.

Trump’s language is, or seeks to be, performative. He speaks to advance his cause and confound his enemies. To achieve this, he will say virtually anything. His followers—disillusioned people who have been stripped of ideals—are responsive to his reckless pragmatism and employ it themselves; they are always ready to use words to “get a gasp.” If Trump ever used words to render reality, I never heard it. Like a committed pragmatist, he uses words to influence his listeners and accomplish his goals. We Americans, natural pragmatists, understand this in a way that no European electorate ever could. His way of using language is all too often ours, which is one of the reasons so many of us are receptive to it.

To be sure, politicians have always wielded language in dishonest ways to serve their agendas. But there is, in general, some articulable and more or less idealistic end—the dictatorship of the proletariat; the creation of God’s kingdom on earth; the dismantling of an unjust social order; the preservation of a just one; liberté, égalité, fraternité—by which the means are justified, even if only cynically. What distinguishes Trump is that he has never claimed—at least not for very long—to have any enduring values in mind. Many voters who were themselves idealists of one kind or another—including, most notably, pro-life Christians—supported his candidacy in explicitly pragmatic terms. Trump invited them to do so not through his half-hearted claims to share their values but through his repeated insistence that he was a winner who would deliver what they wanted. It was this more than anything that made him our first true pragmatist president.

Pragmatism, as Rorty often said, is antifoundational, which sounds dry and schoolroomish but has perilous implications. It means that the validity of nothing is guaranteed. “Authoritative accounts” mean nothing to a truly radical pragmatist. What other people call facts and customs and conventions don’t matter. When they get in your way, you simply smash them, because there is nothing there, no foundation beneath them: they are fictions that need to be exposed as such.

Anything can be caught in the pragmatic game and seen for what it is: not a necessary fact, but a contingent one. And if all ideas and morals and institutions are contingent, then we can do away with them through ridicule, the kind that asks, implicitly or overtly: What good are these things? What good are they to you and me, right here, right now? And if they are no good to us—if they do not give us what we want: the nomination, the election, mass applause and allegiance—then let’s dump them immediately.

Like any good instinctive pragmatist, Trump is thoroughly antifoundationalist. He delights in finding pockets of piety and doing what he can to destroy them. The Trumpist reaction to the 2020 election continues this tradition, trashing that which is still held in some esteem: the integrity of our electoral process. Angry people, profoundly alienated from the status quo, are inclined to find the destruction of ideals thrilling. It’s a great spectator sport.

Does Trump know he lost the election? In a way, it’s an absurd question. It’s a mistake to ask what Trump really thinks about X or Y. Confronted with an issue, he aims and fires—or, sometimes, he fires then aims. Is Trump a racist? Is Trump a sexist? Is Trump a patriot? Is Trump an advocate of freedom? Trump is not anything. He is what will get him what he wants at any given moment. He aligns himself with what he senses will advance his cause—and his cause is himself.

What about Trump’s followers? Do they really believe what they say about the election? Again: wrong question. Trump’s followers are in on the pragmatic secret that Truth has gone on vacation. “Stop the steal!” isn’t a statement of belief. These words are pragmatic weapons. They discomfit liberals. They set the stage for disruption down the line when elections don’t go the MAGA way, and even when they do. The words also function as a password, letting everyone know who is in the club. Something similar could be said about the QAnon conspiracy and other bits of baroque alt-right outrageousness. To judge them as pictures of some objective external reality is to misunderstand their purpose. Cornel West says that pragmatism is about three things: power, personality, and provocation. The stolen-election mantra has no capital-T Truth, but it does have all three of these.

Liberals are often criticized for being unwilling to engage with Trump and his supporters. But you can’t argue with a wrecking ball. You can’t argue with someone who will say absolutely anything in order to score, someone who compulsively “talks for victory.” Rorty himself had little use for arguing the merits of an opponent’s position. He thought that if you didn’t like someone else’s interpretation of experience then you should offer a better one.

It is fairly clear what Rorty would have made of the major alternative interpretation that is currently on offer from the left. He would have seen, embedded in the ideology that treats white supremacy as the great explanatory key to all American culture, the kind of totalizing capital-T Truth that pragmatism aimed to escape. He would probably not have objected to the antiracist movement, the 1619 Project, or their ilk on factual grounds. That racial oppression, violence, and exploitation have been constants throughout American history is a fact. But that these things constitute the meaning of American history is an interpretation—and one that Rorty would have rejected.

Rorty’s own interpretation of American history saw “the struggle for social justice as central to [our] country’s moral identity.” He believed that American leftism had “a long and glorious history,” and he thought it myopic and self-defeating to minimize the movement’s many achievements:

It would be a big help to American efforts for social justice if each new generation were able to think of itself as participating in a movement which has lasted for more than a century, and has served human liberty well.

Anyone who fought to protect the weak from the strong, anyone who wanted a more just, more compassionate, more humane society, merited inclusion in Rorty’s American story, and he would have had little time for the purity tests that have become a central feature of leftist discourse.

“America is not a morally pure country,” Rorty wrote in Achieving Our Country:

No country ever has been or ever will be. Nor will any country ever have a morally pure, homogeneous Left. In democratic countries you get things done by compromising your principles in order to form alliances with groups about whom you have grave doubts. The Left in America has made a lot of progress by doing just that.

Above all, Rorty would have found the left’s single-minded focus on America’s sins ill-suited to bringing about the kind of change he desired. Pragmatism at its best is open, hopeful, and encouraging of more work and development. It points to the future, not to the past. It isn’t held down by tradition. It opens the door for anyone with an idea and some gumption to contribute to an ever-unfolding future.

Walt Whitman, one of Rorty’s heroes, read Emerson, the fount of American pragmatism, and was inspired. In “The Poet,” Emerson lamented that America still did not have a poetadequate to its vast promise.

Our logrolling, our stumps and their politics, our fisheries, our Negroes and Indians, our boasts and our repudiations, the wrath of rogues and the pusillanimity of honest men, the northern trade, the southern planting, the western clearing, Oregon, and Texas, are yet unsung.

Whitman, then an unknown who had accomplished virtually nothing, took Emerson seriously and went on to write “Song of Myself,” the greatest hymn to democracy ever composed.

Rorty would have found our moment in need of new poets writing new American songs: not dirges for the horrors of the past, but hymns to the possibilities of the future.

I listened to Rorty with great respect for his intellect and his imagination, but also with some skepticism, which has grown over the years. Pragmatists like Whitman want things that are, to me at least, worth wanting. He wanted freedom, joy, the possibility for people of all types to get together and have a good time. He used his words to try to make that happen. Trump, as pragmatic as anyone, largely wants things that are not worth wanting: division, suspicion, hatred among Americans, personal power. Trump is about as close to being Whitman’s hateful double as possible. But they are both inheritors of American pragmatism.

Rorty praises George Orwell for teaching us that “nothing in the nature of truth, or man, or history” can prevent a scenario in which fascism triumphs. To the pragmatist, free and open democracy is no more true and authentic than tyranny. There is no special Truth existing on high that you can appeal to when the fascists are winning and you want to set your fellow citizens right. There’s just your vision, your interpretation, which has no more intrinsic validity than that of the fascists.

While Dick was still around, I was ill-equipped to offer an alternative to his vision. But I eventually became the sort of person the committed pragmatist has little time for: an idealist. I came to defend a capital-T Truth that is both traditional and foundational, grounded in what I take to be the three great human ideals: compassion, courage, and wisdom.

To me, education is inseparable from the study and the interpretation of ideals. Reading the Iliad, we can look at Hector and see a glowing image of the citizen-soldier, who though probably more disposed to peace than to war, fights fiercely to protect his city. Reading Plato’s dialogues, we see in Socrates a model of the examined life committed to a disinterested pursuit of the truth. Reading the Christian Gospels, we can study the life and teachings of Jesus who, born in obscurity, preached an ethic of joyful compassion that, in time, spread around the world.

What makes an ideal? In my book Self and Soul, I argue that there are many factors involved. An ideal is difficult and demanding to reach. It requires great effort. And it is not self-interested—its realization benefits not only the idealist but those around her. The ideals place the individual outside of time, in an eternal present, at least while she is pursuing them. They are also risky: Socrates, Jesus, and Hector all died for their ideals. But ideals fill the idealist with a certain kind of joy, a joy that is not identical to happiness. I’m not sure whether humans have souls, but I do believe that when an idealist pursues an ideal, she leaves what I call the realm of Self. She leaves the state where what matters most are our desires and their fulfillment, and enters another state, which I call the state of Soul.

America has long been a nation of ideals. People have been stirred by the Founders’ commitment to equality and their endorsement of freedom. We’ve been moved by Lincoln and his unforgettable endorsement of democracy in the Gettysburg Address. We’ve been captivated by Martin Luther King Jr. and his dream of racial harmony.

American culture has always sustained a tension between the ideal and the pragmatic, and this tension is necessary. Our ideals need to be tempered by a dose of common sense. Otherwise they are vulnerable to the kind of dangerous exploitation that made Rorty want Truth to take a hike. We should never forget the idealist underpinnings of twentieth-century totalitarianism.

But if some nations have proven susceptible to toxic idealist nonsense, Americans have become more and more receptive to toxic pragmatic nonsense. Many Americans now seem ignorant of America’s own ideals.

With the declining belief in American ideals of equality, freedom, and democracy, the balance between pragmatism and idealism has blown up. Pragmatism has won the field, and Donald Trump has shown us quite clearly where pragmatism unchecked by idealism leads.

The ideals I want to endorse are not specifically American. In fact, I think of them as universal. Every culture in the world values compassion, bravery, and wisdom. Throughout history, people have celebrated those who protected the weak, those who took care of people in need, and those who guided others.

Granted, different cultures have different ideas about these virtues, and even within cultures there is dissent. But these ideals draw the interest and usually the admiration of almost every thinking, feeling individual. Rorty himself lived out these values—he was tirelessly compassionate—even as he found them to be philosophically indefensible.

The discovery, promulgation, and debate of the best that is thought and said about subjects that truly matter to the conduct of life seems to me in line with the kind of genuinely democratic culture Whitman wanted, one that encourages citizens to become virtuous, free, and aware of what they value and why.

When I hear the antiracist, antisexist, anticapitalist rhetoric of the left, I often respond as I think Rorty would: with the pragmatic sense that theirs is a platform unlikely to inspire a broad electorate, a platform far from Rorty’s hopes to achieve our country through solidarity with the working class and the poor. But I also sense that hiding beneath the rhetoric are profoundly held ideals, ones that are struggling to express themselves in a postidealist age, in the pragmatic language that is all we have left.

Trumpism—if not Trump himself—will be with us for some time. But the great majority of Americans are hungry for something more or better than Trump can offer. To flourish as individuals and as societies, we need ideals. We need to work to arrive at a stronger and more refined sense of what we mean by courage, compassion, and wisdom. We should do what we can to introduce these ideals into our lives and into the lives of our children. Rorty’s mode of opposing bad pragmatic stories with useful and humane pragmatic stories is a recipe for chaos. It allows for lies and obfuscation in a world defined by competing interpretations, one in which there is no solid ground to stand on. We need solid ground. Thousands of years of history and culture show us what humans at their best value: high ideals, energetically pursued. Truth has been on vacation long enough—it’s time to put it back to work.