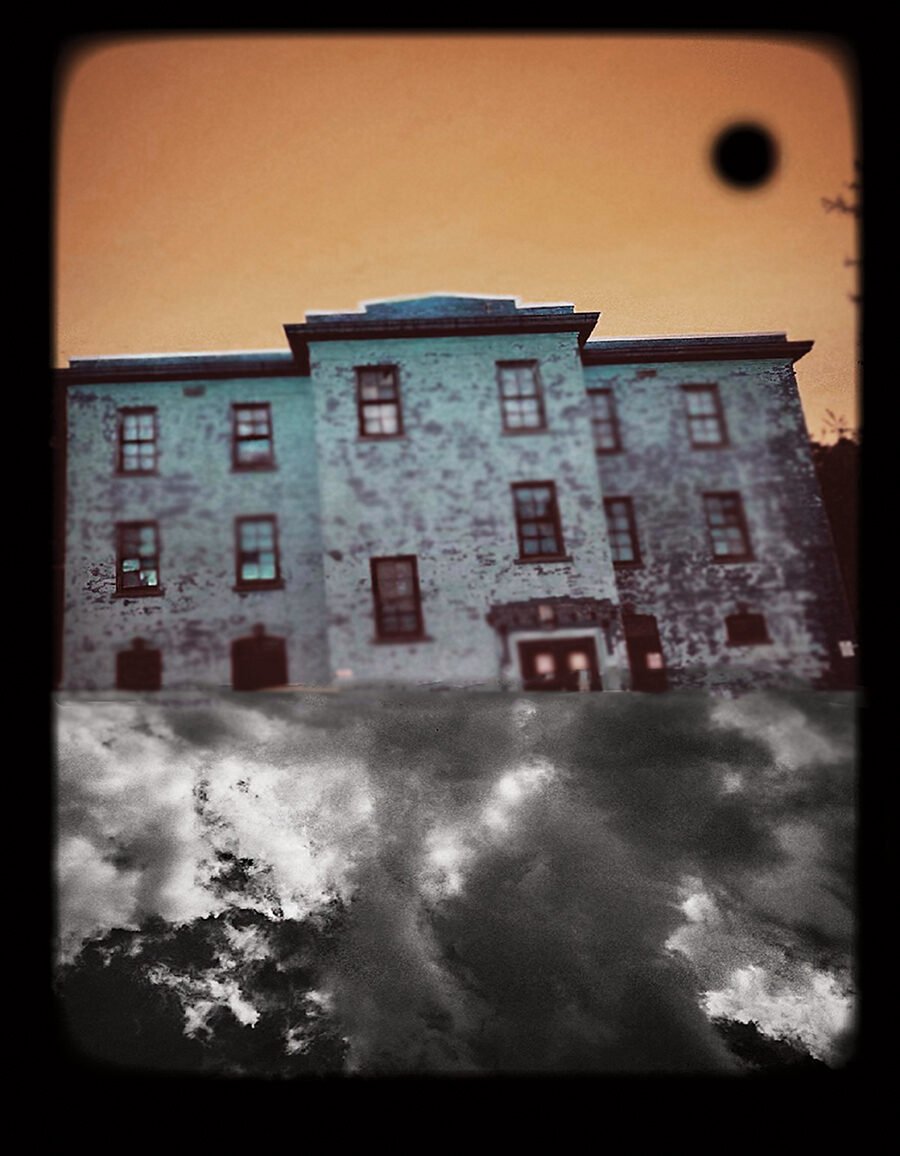

Photo collages by Gerald Slota

I lived at a state mental institution once. At, not in. My father—almost, it seemed, as if he were attempting to externalize a madness that had been flickering in his own brain for decades—lurched from family medicine into psychiatry in his forties. First there was private practice, soon aborted. Then a stint at a flatland hellhole for all the blasted addicts and harmless, homeless maunderers of north Texas, where time ticked and stopped and ticked like a hidden cricket, and even the slow, heat-warped air seemed sedated. Ever inclined to boredom, ever upping the ante, he began traveling one day a week to the State Hospital for the Criminally Insane, returning as becalmed and refreshed as if he’d been at a spa. He was at home there, my father, in that home for people whose souls are utterly, fatally homeless. It was no surprise that when a staff position opened up he leapt at it, and no surprise the extent to which he vanished into that blessedly unprojected bedlam, all the time and attention he lavished upon his shackled, unmythical monsters. If the subject of retirement ever came up, he swore they’d have to carry him out on a stretcher. Which they did.

But that’s not where I lived. I lived in an earlier circle of hell, where the most dramatic things that ever happened were the rare bobcat sightings that everyone, sane and not, seemed to have but me, and those sudden, earth-altering, north Texas thunderstorms from which everyone on the hospital grounds, sane and not, ran like wraiths. That’s not to say there weren’t characters. Angela, for example, who was obese and bursting out of cowgirl clothes and screamed expletives at the sky like a rodeo Medea. Or Leon, who on his good days roared around the field between our house and the hospital with his arms spread out, and on his bad days walked from person to person asking if they had an extra flap, a functioning rudder, an uncracked aileron. (Leon was an airplane, you see.) Or Phyllis, who had bees in her bones, and was so winnowed, harrowed, and nearly transparent that it seemed the sunlight streamed right through her. She was so anguished and eaten alive with pain that some nights I could hear her moans.

Phyllis lived in the house, not the hospital. Phyllis was my father’s wife, not a patient. Phyllis suffered from advanced bone cancer, not bees. The bees are of my own brain, you might say.

It was my job to watch over Phyllis during the days, to make sure that she got something to eat and drink, that she could go out into the sunlight if she wanted, that she had not wet herself or otherwise compromised her dignity, that—in the long silences when the ticking cricket stopped—she was not dead. It was a small house with cheap carpet and a makeshift wheelchair ramp out front and a loaded .44 Magnum on the bookshelf and prescription drugs piled high like plunder in every closet. I was a twenty-two-year-old boy with a badly plugged well of unfocused rage and a vague smear of self and literary ambitions that seemed to stand no chance in this tiny dry asylum existence to which I’d been reduced. I was there for two months, or maybe six. It all blurs together. I was punctual and careful, conscientious and solicitous. You could call that caretaking the most Christian act I ever performed, except that I was getting paid (by my father) and I did it without love, or with only an abstract, humanistic sort of love that would have made Christ—that avatar of, and antidote to, the horribly solitary and singular nature of ultimate human pain—spit in disgust.

I was also—somehow this seems most distasteful of all to me now—taking notes. In my free moments I’d write down the things my father mentioned to me about the patients, or details of my own encounters with them, for they and I could wander around freely and at times interacted. (Once, in what had to be a breach of professional ethics, he even let me sit in on a group session. It was dull.) I’d try to reconstruct the word salads to which Phyllis, as the cancer advanced into her brain, was increasingly prone, and I’d note the red-winged blackbirds shrilling “dementedly” on the cattails near the lake, and the “spirit-like” sandhill crane so sensitive and elusive you became aware of it only as it disappeared.

Those notes, and the mind that needed them to hold this all-too-actual madness in place, eventually exploded into a four-hundred-page novel I wrote in a fevered year a decade later. It was about a loveless and godless photojournalist named Adam, who in his early thirties returned to Texas and the state mental institution where he’d been raised, because his father—a man for whom facts were merely imagination’s medium, a man whose absence and presence created acolytes and refugees in equal measure, a man whose firstborn could only be named Adam—had come home from work one day, sat down in a living room with cheap carpet and crappy furniture and a gun on the shelf, and shot himself in the head.

That was all on the first page—in the first paragraph, in fact. The rest of the novel consisted of Adam being drawn deeper and deeper into the world of the hospital, and his own past, and his own mind. His guide, so to speak, was an enormous, mysterious patient named Tobias, who, Adam would slowly learn, had been very close to his father, and who seemed to know a great deal about Adam’s childhood that Adam didn’t. Intelligent, articulate, and sometimes violent, Tobias was neither sane nor insane, quite, but of some wonderfully but dangerously creative existence that made those designations inadequate. Endless identities emerged during the course of the book—Tobias had been a preacher and a judge, a murderer, a martyr—all of which were subsumed in the one he now claimed for himself: I am that I am. Everything in the novel built up to a confrontation between Adam and Tobias, between the first man and the last god, you might say, which I could feel all during that year like a strong gravitational force, and which I longed for and dreaded in equal measure. “I will give you the treasures of darkness,” Tobias says, quoting the prophet Isaiah, the first time that he and Adam meet. But he didn’t.

It is a strange feeling to strand characters who have meant so much to you, to feel their existences at once stop and continue in some dimension to which you have no access, like the known universe expanding into nothingness. No access is not quite right, I guess, since I have in my head some of what transpires between Adam and Tobias in that last chapter (Adam has to either kill him or love him—or maybe both), though I have never written it down, and now—because the thread is lost, the spark is snuffed out, two decades have intervened—never will. To compare the novelist to God is an old habit, but a better comparison is between a failed novelist and God, who seems conflicted about how—or whether—to finish us. And now I can almost hear Tobias’s low chuckle as he savors the irony: that I who in my novel could not believe in God should, in a chastened essay of contrition or compensation or atonement twenty years too late, make myself into one.

Other characters, too, are still surviving—and still suffering—in me. Most are from the west Texas world of my childhood: laconic, plain-faithed people whose lives happened in gashes sewn shut with habit, and who—in that flat, cracked land, among its bristling cacti and thorn trees—seemed like animate instances of the landscape. There was Theta, Adam’s mother, who, like my own mother, had Indian blood, and who, unlike my own mother, died in mysterious circumstances when Adam was a small child. There was a love interest (I had, I should admit, a money interest): Quinn, also a doctor at the hospital, was smart, attractive, spiritually complicated, and perfect for Adam in every way but one, which he wouldn’t learn until it was too late—she had slept with his father. There was a patient who thought he was an airplane, another who was obese and wore cowgirl clothes and screamed invectives at the sky. Bouncing off all of these characters, binding them together and to Adam, was Nicky, his younger sister, who had been wild and wayward and, though much better now, still lived in the embers of that extravagant personality. She was all warmth to Adam’s ice, all earth and living instant to his distant, uncertain self.

Wishful thinking, that. My own sister, upon whom Nicky was closely modeled, has never emerged from the fires in which she lived, though now there are no fires, no embers, only ash. We speak of people whose spirits have died in them, but in my experience this is not accurate. A spirit whose natural expression is either denied or thwarted—at least in people who make you want to use a word like “spirit”—does not die but is transformed into a ravening abstraction that ghosts the person it once enlivened. That’s my sister. At some point all the singular and vital energy that made a space around her in which you wanted to be, all that life and laughter, seemed to stop at the edge of her skin, and then began eating inward. She isn’t “needy.” She is need itself, and her hungers can suck the life right out of sunlight. I remember sitting one Christmas in my mother’s small apartment in Abilene, reading aloud the relevant passages from the Gospel of Luke, which, at that moment, it would have been easier for me to eat, everyone feeling for their wallets and watches, everyone pretending that my sister, with her glassy, jagged laughter and simultaneous cigarettes, her infested skin and fiending knees, was not using again.

This was after I had abandoned the novel but before it had, so to speak, abandoned me. (I still thought I’d finish it someday.) It was after I had fallen in love with the woman who is now my wife, but it was before I had fathered twin girls who now bloom and scream in our days (and nights . . . ) like the earthiest incarnations of hope. It was after I had knelt down one day and assented to the faith that had long been latent within me, an ironclad resistance it would take my own diagnosis of cancer to crack open, but it was before I came to understand that the greatest danger to that faith would be not the dramatic crises of my life or the abyss of unbelief over which I am constantly suspended, but the endless succession of days in which nothing changes, no one ever changes. It was after my father showed up unexpectedly during the last hours of my wedding party in Washington, stumbling from guest to guest with a nimbus of affliction around him much larger and darker than the black hat he actually wore, but it was before my sister, with a child’s tensed-lip determination I can almost see, had carefully cut in half a Coke can, stuffed her mouth with an institutional towel, and dug one wrist down to the bone.

She was in prison then—serious prison, a two-year stint among some of the most hardened criminals in the state. At some point she began writing letters to me, though aside from those tense Christmases (and they were all the same), we hadn’t really communicated since I’d left for college. The letters were earnest, God-haunted, well-written, disturbing, funny. I suspected it was that last quality that was keeping her alive in that place. It was suddenly easy to remember the person she had once been, easy to imagine her cracking jokes so brash, strange, and annealed with self-mockery that they could surprise violence into laughter. Other people’s violence, that is.

One summer day when I was visiting Texas, before my sister had smuggled away that Coke can, my father and I made the five-hour drive down south to see her. Phyllis was long dead. His third wife had left him and his fourth was, even at that moment, and though she was just slightly older than me, dying. I would have said my father was dying, too, as he was aphasic, and half-blind, and tottered about in some combination of early senescence, late-stage drug abuse, and the residual effects of blunt trauma to the brain.

He’d been attacked. The decline had begun several years earlier—come to think of it, my father’s entire adult life seems to me a decline—but the physical debilitation, and then the avalanche into complete, ostracizing addiction, began about ten years ago. He had, unsurprisingly, landed in one of the most difficult and dangerous positions in the hospital. His job was to “diagnose” patients, determining whether or not a given individual was sane at the time of the crime; and since this was Texas, which leads the country in executions, and since in many instances these were men and women who had killed, often my father’s diagnosis was a sentence of life or death. Protocol called for restraints and guards. Gradually my father got rid of the restraints, and then he got rid of the guards. He wanted to “get inside the heads” of people who, in more than one instance, had quite literally chopped other people’s heads off.

There was one man—immense, intelligent, inscrutable—who fit into this last category. My father got to know the man, befriended him, I suppose, and learned not only of his predictably awful childhood and his appetite for intimate death, but also his aspirations, his inner turmoils, his “demons.” Thus it was a great surprise to the man when, at the hearing to determine his sanity, my father testified that the man was in fact quite sane, that he had known exactly what he was doing and should stand trial for the murders. A greater surprise, though, was in store for my father, who sat dumbfounded and enraged when the judge, who in most instances simply signs off on the conclusion of the psychiatrist, inexplicably decided that the man was out of his mind. There is one natural destination for the criminally insane in Texas. There was one place for that man and his new purpose in life, his consuming and almost blissful sense of vengeance, to go.

Six months passed. The man was relegated to the remote and mostly sequestered wards for those who had committed the most violent offenses. One night after my father had worked fifteen hours straight, he was on his way home. There was a rule in the hospital that no one who worked there was ever alone. The patients had some leeway to wander, and though they were, as my father said, “chemically restrained,” attacks and fights were still frequent, and there had to be another person present who could at the very least call for help. On this night, though, everyone was gone or far dispersed, the wards were all locked down, and it seemed to my father foolish and even selfish to call a guard simply to walk him to his car. Foolish, too, not to take the shortcut through the dining hall, which was empty at this hour. He was already ten feet into the dark room, anticipating his first bourbon and Vicodin cocktail, before he saw that wrathful and single-minded man sitting calmly in a little folding chair as if he’d been waiting there for six months, smiling as he stood with his arms extended as if for an embrace.

My father told the story without bitterness, made it seem entirely his own fault that his jaw had been shattered like sandstone, one eye half-gouged out, every rib cleanly broken with professional precision. There was almost a sense of excitement, in fact, or at least a kind of pained awe whenever he would set to wondering again at the devotion and calculation the man had shown, the coming together of chance and plan, the almost artistic ingenuity of it. And then—this best of all—to walk away, to take a life without taking a life, to kill only the spirit, to murder metaphorically.

The visit with my sister was two hours long. It felt like two months. My father and I quickly got in an argument over, of all things, global warming. (My sister seemed not to have heard of it, though she may have cannily feigned that.) Then there were some rote questions and answers about life in prison, innocuous talk about my sister’s two teenage sons. I remember my sister, who has smoked since she was fourteen and now suddenly couldn’t, devouring candy bars and downing sodas as if all her manic intensity had turned to sweets. I remember guards walking over once when a prisoner’s hands disappeared from on top of the table, making her stand, patting her down. Mostly, though, even though the room was loud, and even though we were speaking, I have the sense of silence—a vast and essentially lifelong silence—in which our various madnesses grappled like tarantulas on the table between us.

The end of the visit, though, had some bite. With about fifteen minutes left, my sister asked me—suddenly, ingenuously—how I lived with death, what it was like to feel it so close to you all the time. I told her—hesitantly, disingenuously—that one gets used to it, that I had no symptoms at the moment and thus the disease was largely abstract. She asked me if I believed in God, and I said yes. She asked me if I believed that God would forgive anything, and I said I didn’t really think about God like that, that I didn’t think of him as an entity that judged and loved as we understand those terms. Whether she was confused by what I said or saw it for the evasive sophistry that, in this context, it was, she merely paused. After a minute she said it was amazing how present Christ was in this place, how she could feel him here as she never had before; how sometimes from the very center of suffering—these are not her words, I forget her words, or maybe there were no words—there bloomed a seed of being. Not meaning. Being. A peace of and with being, and a peace that being, when the self it sparks is entirely ash, will not end.

My father took her hand. Then—dismissing me, it seemed—she asked if I would buy her one more piece of candy. I bought it, took it to the guard for him to unwrap (apparently at some point some very clever and determined criminal had figured out a way to fashion a weapon out of candy wrappers), and carried it back to the table. My sister’s relationship with our father has always been even stranger—at once more intimate and more poisonous—than my own, and whatever kinship or abyss they had broached while I’d been gone sealed shut as I returned. My sister made a joke about how she was going to get fat (she was brittle and bony, her very self a cell), and my father shook his head laughingly and said how stupid they were at this prison, that they would insist on unwrapping the candy bars while allowing the prisoners to have cans of soda, which any fool could cut in half to cut a throat. My sister, chewing that last candy bar without relish, never even looked up.

Such drama. Such cinematic details. It’s probably obvious why I might have wanted to write a novel out of this “milieu.” Perhaps it’s also apparent why such a project might have been doomed. It’s not that I was “too close to my material,” to use the common—and often correct—workshop diagnosis. It’s that I wasn’t close enough, and my demand for distance, my fear of exploiting my subject—my fear of my subject—led me to impose an elaborate plot on material as uncertain and volatile as atoms, to move too freely, too confidently, through the dense and tenuous layers of memory, elasticizing facts, hypothesizing God.

What I want to say now—it will sound crazy—is that these people are not crazy. (These people—as if I weren’t one of them.) They are not Faulknerian characters distilled to their most dire moments and neuroses. Or perhaps they are just not “characters,” and that’s the problem. I want it to be fiction, just as I often want God to be pure imagination, pure mystical abstraction, and not, for instance, the harrowing call of Christ in the dying eyes of someone I do not love. My family’s story often feels like fiction to me, especially when I try—as I have been trying here—to tell it to other people. But then something happens, and I experience again the ruthless, relentless nature of its truth.

In 2009, I went home to take care of my father’s affairs—just like Adam in my novel, I guess, though that didn’t occur to me at the time, probably because my father was not dead, at least not biologically. He and my sister—who had survived her suicide attempt, and survived the inexplicable (and inexplicably brutal) month in solitary confinement that followed—were living in a random house outside of Fort Worth. Because of multiple instances of fraud, my father’s accounts had been frozen, and because neither he nor my sister could figure out how to remedy this situation, they were screaming into a hell of withdrawal together. My sister called every day to tell me dully that our father was now naked and waving his hands in front of the television, that he had found the keys and taken the car and crashed one side into “something green,” that the water was turned off and the dog was gone and “the state” was snooping around and goddammit she was about to bolt. I went home because I’m the one who gets called, because I’m the one who escaped, because I’m the one who, though always without any capacity to actually change things, at least won’t fuck them up even further. I went because I always do.

My novel began with Adam in an airplane imagining the town of his childhood, which was the town of my childhood: hot, flat streets and functional houses, a few scattered ranch-style approximations of opulence; the squat high school and the underground pool hall (rough intellectual equivalents); the square with its ring of dusty stores that fused failure and survival into a single aspect. Anchoring the square, or maybe crushing it, was the garish fake-marble courthouse in front of which stood the albino buffalo statue that had given Adam nightmares his entire life, and had given my novel its name. Sacred to many Native Americans, the white buffalo is almost inconceivably rare (one in ten million), and it must have seemed to the town’s founders, when one of them sighted, and then blasted, a single white life in a sea of brown, a brave thing to commemorate. I saw it when I was home. I sat for a long time outside of time and thought of the clear but inexplicable image that had first prompted me to write a novel, and I wondered whether it was because I could never figure out exactly what the image meant, or because I so desperately needed it to mean that the novel, which is dead in me, wouldn’t quite die. It is far west Texas. It is the middle of the night in an empty square, and there is a small boy standing quietly while his young mother, with a strange elation the child can’t quite find a way to share, paints an albino buffalo statue bright red.

After eight abrading days in west Texas, where everyone had gathered at my mother’s apartment; after tracking down accounts and the people who had been stealing from them; after talking to lawyers and doctors and angry debt collectors; after hiring a home health service to come in every day of the week and take care of my father because he refused to consider any sort of assisted-living arrangement; after my sister had vanished; after I had learned that I was going to be a father, on the phone in a room adjacent to the one in which my own father lay on the floor moaning that he wanted to die, someone please just help him die—I went into the living room and picked my father up from the floor and helped him into his half-wrecked car and drove east to that rented, random house where he knew no one.

It took him five minutes to stop crying, ten to start talking, though it was difficult to hear him over the wind blasting through the broken door. Finally I did hear him, though, and he was telling me—or maybe just telling the landscape—a story about a patient he had once “treated,” a story I had heard long before and had in fact put in the mouth of my imaginary psychopath, my lost psychopomp, Tobias.

Once there was a place that was hell, or it was heaven, depending on whose eyes, whose heart, was seeing. Once there was a man who had no reason whatsoever to live, or had every reason, if you could only see collecting Saran Wrap from Jell-O salads, from Sunday brownies and the pale shallow little bowls of institutional green beans, as a reason. The man was small and quiet and had been in this place for so long that no one remembered what had first brought him there, nor did anyone know that the man’s calling—and it was a calling—had become to collect Saran Wrap, for he pursued this passion as he did his life: furtively, hyperalertly, alone. Whether it was this self-sufficiency that accounted for the length of time it took for the man to complete his project, or whether he was working on some timetable that providence itself had laid down in his brain, it took a solid four years. Four years of squirreling away scraps of Saran Wrap; four years of secretly kneading those scraps at night into a ball, weighing its balance, testing its heft; four years until the dawn sun struck the hallway window at just the right angle or the guard’s ring of keys clinked a known tune or a bird spoke with a human voice, and one morning when the cell door slid mechanically open the man walked out and bashed in the skull of the first person he saw.

“Can you believe that?” my father said when he finished the story, which did not differ from the version he had told me long before, and not in its essentials from the version that had made its way into my novel. (“I made up that place,” Tobias says—or was going to say—to Adam in the last chapter. “I made up that man.”) “My God,” my father said, laughing quietly and muttering something to himself while I stared straight ahead at the feints and taunts of heat rising off the road, and the land mashed flat all the way to the horizon, and the sky so empty that it had no end.

§

I need some kind of coda. Sometimes I think that’s what my entire life with my father has been—a kind of coda. That the original work it follows never existed only enhances the effect.

Also, there was a miracle.

Twelve years have passed since I wrote the essay above, which has been simmering all this time in a desk drawer. It was scheduled early on to come out in a magazine, but I withdrew it because—well, I didn’t really know why, actually. I knew only that something about it felt deeply wrong. Now I know.

My father died of an acute polysubstance overdose in 2014. At the time, he was living in a residential motel so close to the freeway you could touch the hum of tires in the walls. My sister, a few years out of prison but once again a dead-eyed addict, shared the single room with him, their lives demarcated by fixes and, at his insistence, Fox News. My father was a Trump supporter the minute he descended the golden escalator.

Two months before my father died, responding to a sudden tug in my gut, I went to see them. I was changing planes at DFW Airport and spontaneously decided to add a day to my trip. I stayed (snobbishly, he let me know) at the non-residential hotel across the highway. “Come into our parlor, my son,” he said, gesturing expansively at the space between the television and the foot of one of the beds. There was in fact nowhere to sit aside from the beds, so that’s what we did, almost knee to knee, my father and my sister competing to show me the motto some previous occupant had carefully calligraphied into the bed cover—fuck da money. trust no one—and all of us trying, and then failing, to keep from erupting into the old ironic laughter that implied intimacies long demolished.

We all pretended it was perfectly normal for them to be living in this diesel motel in this tumbleweed nowhere. We even spoke of them perhaps renting a place together in Fort Worth again because my father’s state pension paid him $70,000 a year. Even given the illicit expenses, there was an element of willfulness to the rot and squalor.

And it was squalid. As far back as I remember, I can see my father coming home with disjecta membra from humanity’s underside. Games with some crucial piece missing, used exercise equipment that never got repaired, sections of fencing that remained stacked in the backyard for years. This was no different, only compressed. Belongings were piled everywhere. Dishes overflowed the sink. Food was crammed in every cabinet and the refrigerator, half of it rotten. There were vats of some powder that promised to fulfill one’s nutritional needs, along with an expensive blender that had never been used. A couple of years later I would read Elizabeth Hardwick and be returned immediately to this room.

These people [that phrase again!], and some had been there for years, lived as if in a house recently burglarized, wires cut, their world vandalized, their memory a lament of peculiar losses. It was as if they had robbed themselves, and that gave a certain cheerfulness. Do not imagine that in the reduction to the rented room they received nothing in return. They got a lot, I tell you. They were lifted by insolence above their forgotten loans, their surly arrears, their misspent matrimonies, their many debts which seemed to fall with relief into the wastebaskets where they would be picked up by the night men.

I—the night man—took my father and sister out to Red Lobster that evening, where my father had a hard time chewing the food and kept pulling out his dentures and cursing. My sister, also dentured, pulled her own out at one point and clacked them in my face to punctuate just how amusing she found me. We talked openly and almost entirely about drugs—the allure, the fidelity of them, the existential relief one feels to know this thing is there when you need it (unlike family, I did not say, unlike art or God), and the demonic ferocity of their claim. Serious drug withdrawal is, in my experience, worse than extreme chemotherapy, because you feel not only that your body is tearing apart but your soul as well. A single shudder passed through each of us, another simulacrum of shared life, shared grief.

We were almost finished with dinner when my sister asked me the same question she’d asked when we’d visited her in prison: what it was like to live with death all the time, how one made it through one’s days. The first time I had been irritated, as I always am when someone brings up cancer when I am not thinking about it. This time, though, I was shocked. Surely if anyone knew what it was like to live with death all the time, it was she. The suicide attempts (I have related only one), the hepatitis gnawing at her liver, the undifferentiated days enlivened and annihilated by mainlining little hits of death itself. I said no one lives with death all the time any more than one lives with God all the time. I said it goes away, that terror (that joy), when it isn’t actually burning in your bones. I said some other useless shit. As with her question to me in the prison, I couldn’t understand that she was asking not out of curiosity but risking a real despair and an immediate need. Somewhere in the ruins of her life (“ash” is how I callously describe it above) there was a spark still burning—and seeking help.

My children were five when my father died, and had never met him. That was of course intentional on my part and I have no regrets. He was, for the most part, a gentle man, but he attracted catastrophe in the way certain people attract lightning strikes; and as with those people, every survival only increased the likelihood of another blast. By the time my children were on the scene, my father was sizzled.

Still, I wish they could know something of his charisma, his capacity for surprising kindnesses, his utter grudgelessness and deadpan humor. One day they will read of him here and be even more baffled than I was.

My sister, though, they know, and love, and this is why that essay above sat for over a decade with an unacknowledged sin festering in it. And I do mean sin. Because it wasn’t something wrong with the essay that kept me from publishing it, but something wrong with me, who had, in terms of my family and my relations to them, sunk into the form of despair that doesn’t simply refuse hope but actively snuffs it out. I should have realized that a person who can find Christ in hell, as my sister did in that prison, who can see Christ working in hell and love this work even as that balm is withheld from her, is not a person whose soul is dead. Why must I learn the same lessons over and over again? That both life and art atrophy if they are not communing with each other. That it means nothing to make a space for the miraculous in one’s work if one can’t recognize some true intrusion in one’s life.

The moment my father died, my sister, whose addiction to drugs had defined and destroyed her entire adult life, stopped using. It was as if the instant she touched the one death we all share—and I mean this literally, because she was the one who found our father—all the lesser deaths lost their charge. Not that it was easy. She shouted and shook and vomited and moved through a solitude so black that her funeral clothes seemed a reprieve. For days she sat out on the porch of my mother’s apartment clenching her knees as if parts of herself might fly off in a wind. But slowly, week by week, the talons that for decades had gripped her loosened, and her soul slipped free. And brightened.

Hope [is not] hope until all ground for hope has vanished.

[Hope] is a state of the soul rather than a response to the evidence.

We live in memory, and our spiritual life is at bottom simply the effort of our memory to persist, to transform itself into hope, the effort of our past to transform itself into our future.

Keep your mind in hell, and despair not.

Familiar quotations to me, all of these (in order: Marianne Moore, Seamus Heaney, Miguel de Unamuno, Silouan the Athonite). I have used them in this essay and others, have spoken them hundreds of times from podiums. I have so internalized them, in fact, that in more than one instance I have simply uttered them as my own. (Intelligence isn’t intelligence until all intelligence has vanished.) They have all been deeply consoling and useful to me in jolting me out of my own despair—and apparently useless in freeing me from the static despair, or from my perception of a static despair, of my family. Could it have been otherwise? To some extent. Sometimes we want despair to be ultimate because it absolves us of action. Sometimes we simply seek protection from pain that in the past has found us too exposed. I’m sure my detachment included both kinds of cowardice. And yet, for all the active attentiveness and readiness it requires, perhaps hope, in the end, is like joy—not willed but given. By God directly sometimes, as came to my sister when she touched my father’s death and turned decisively toward life. By God indirectly sometimes, as has come to me as I have finally faced this essay and the sin that lay at the center of it: a willed death of hope in the face of a fragile but furious will to live.

Now more years have passed. Now my sister is a tender and eccentric aunt to my children and a loyal friend to my wife. Now I can see that the destroyed person who lay naked (another inexplicably brutal punishment) on her cell floor with her wrists bandaged is the same indefatigable soul who, in time, puts her ear to the vent to catch—and save—the fragments of voices and lives that come to her from the other cells. And the child who could not only spark adults to laughter but then fuel the blaze by imitating their laughs—this is the same morose and imploded woman who meets me in that dreary motel room the day after my father’s death.

She is in early withdrawal, but I don’t yet know that. I have come straight from the airport and have brought us sandwiches and two peaches which sit untouched because a woman from next door has skittered in behind me and is now picking up one random thing after another asking, “Are you going to keep this?,” “You won’t need this, will you?,” and even, “Your father told me I could have this.”

I am too tired to be amused, much less polite. My sister is sulfuric with hate. One of us is about to be cruel.

Suddenly, all in one gesture, the woman grabs one of the peaches from the bed, takes an enormous bite, and drops it back down on the fuck da money blanket, talking (now smacking) the entire time.

My sister and I both stare at the bitten peach. Then, at the same time, we lift our gaze to each other, and it’s as if forty petrified years suddenly crack open in a jag of laughter so anarchic and original that even the crazy neighbor—still talking, and with apparently no inkling of its source—can’t keep herself from joining in.