Illustration by Chloe Niclas

Discussed in this essay:

Predator, by Ander Monson. Graywolf Press. 264 pages. $16.

Children, do you remember Predator? A Reagan-era sci-fi action movie in which a team of black-ops commandos, led by Arnold Schwarzenegger, is called on to find, somewhere in the jungles of Central America, another team that has gone missing. Said lost are located: dead, skinned, and made into ornaments hung in the trees. It will turn out that a highly evolved space-biped is hidden in the jungle, hunting human beings. He will kill all the soldiers, one by one, until only Arnold is left, the true battle then—ding-ding goes the bell—on.

Let’s say you haven’t seen it, and my sketch is all you have to go by. Reasonably, you’ll assume Predator to be a laughable exercise in bang-bang and biceps and, given we’re talking about a sci-fi movie from the Eighties, laughable in its (likely not very) special effects. Or, let us assume that you have seen it, at eighteen, but in the three decades since its release—during which have followed its seven undistinguished-to-unwatchable sequels and spin-offs; its twenty-eight fair-to-middling (research suggests) video games; its twenty (at minimum) novels and novelizations; its one card game; and two board games—you have tuned out its various byproducts as sorrows on a culture already too full of them.

But were you watching it for the first time, or were you watching it for the first time in thirty-five years, as I just have—due diligence so I might consider the merits of the book occasioning this essay, Ander Monson’s eponymous memoir-cum-critical-reading of the movie—you would face a difficult realization. The movie, plausibly terrible, is actually a masterpiece. I use the word in its humblest, dehyperbolized sense: a piece of work by a craftsman accepted as qualification for membership in a guild as an acknowledged master. It’s directed by John McTiernan, whose first movie, Nomads (1986), was extremely bad, and whose next movie, after Predator (1987), was Die Hard (1988), which for most action aficionados remains the genre’s high-water moment, McTiernan the Orson Welles of the form. But on rewatching Predator—and all of its despairing sequels, as well as McTiernan’s highly uneven filmography—that jungle movie seems, more fairly and more purely, not only McTiernan’s best movie, but the most cinematic in the genre’s history.

For long stretches, Predator is both silent and still: there’s much lying in wait, given the whole “hiding monster coming to kill you” idea. Through that stillness and silence, McTiernan’s gift for understanding movement itself moves, with bursts of legible action—none of the jumpy-cam jittering or super-slow porno of our degraded present—that exhilarate not because you can’t believe that anyone could do what the commandos are doing, but because you absolutely can. The scale of the proceedings is human, and the pace is human, the triumph of the Schwarzeneggerian will over the space alien is human, too. Zero suspension of disbelief required. As is the case with the work of all truly gifted directors, we are not asked to believe or made to believe. Unbelievably, seeing is believing.

Perhaps most unexpectedly, Predator is strangely moving. It’s an ensemble piece, with Carl Weathers and Jesse Ventura and all sorts of gorgeous male humans with bared glistening man-parts who crush their sentence-fragment lines. Lots of steely stares between jacked American muscle. But there’s something going on behind the caveman exchanges. A queer—all senses present—tenderness. Call the movie Men in Love. And Arnold! So easy, then as now, to laugh at as a cultural figure, but he can’t be laughed at retrospectively. He’s calm, not wooden; fierce, not foolish; intelligent, not doltish. One hadn’t noticed. One can’t not notice.

For any doubters of my claims, I endorse the recreational use of Monson’s book. It’s unlike anything I’ve ever read, and it feels like it shouldn’t work at all. It’s structured as thirty-one essays that march chronologically through the movie, each parsing what’s going on in the film’s significant scenes and shots, less at a technical level—though Monson is good at that stuff—than a metaphysical one. His enterprise is ultimately anthropological, a look at a culture in which guns are central and entertainment with guns is focal, but without cant. The book really revolves around Monson, each of his chapters about the movie becoming chapters that maunder through his life, cleaving away at the monster of manhood. “I don’t mean to be the subject here,” he writes, “but I do mean to be an instrument. I am a thing on which an effect is registered.”

Monson’s book brought up uncomfortable feelings in this reader, as if I, too, had become an instrument: a gong, one on which he beat away, mercilessly. Predator had the effect of an awakening, as if a dormant part of myself, asleep in an unswept corner, had been made to shoot to its feet, fangs bared. How dare he, was the feeling. How dare Monson remind me of something I had gone to great lengths to repress: how much I loved action movies, and how much of my young adulthood I had spent, and misspent, trying to understand precisely how they worked, not merely the mechanics of mayhem up on the screen, but the more mysterious matter of how they were assembled on the page. For as much as my interest was, like Monson’s, authentically anthropological, it was also practical. It was my life’s ambition to bring my poetic patience and scholarly passion to bear as I tried to write them.

Let us begin in 1993, when I met a man in a bar in New York City. He was very tall, very pale in the way that redheads often are pale, although, if I’m clear-eyed and cruel, he had about him the deathly pallor of the reaper. He was gesturing a lot. His voice carried, and it suggested either someone whose enthusiasm was uncontainable, or a person cunningly aware that the germs of what he was saying would infect a certain kind of listener. He was—you will be genuinely surprised to learn—talking about gallons of water. More specifically, he was offering a riddle: Given an empty five-gallon jug, an empty three-gallon jug, a water source, and a timer set to five minutes and counting, how would you fill the five-gallon jug with precisely four gallons of water? Not as easy as it seems, the fiend made clear, especially given the stakes. Were you to believe that you had managed this tricky proposition—reader, try it yourself—within the allotted time, you were to set the jug on a scale, a scale connected to a detonator, a detonator connected to a bomb, a bomb that would, were your four gallons actually 4.1 or 3.9, explode somewhere in New York City. But were you to succeed in your mission, your four gallons would defuse the bomb and save the day.

The man in question was not a terrorist, at least not in the conventional sense. Rather, he was a screenwriter named Jonathan Hensleigh. He would, as I have said, visit, in 1993, the bar of the restaurant where I, for the most part, waited tables. Fueled by, if I recall correctly, martinis on the rocks, Hensleigh would expatiate, in his admittedly compelling way, on riddles and jugs and scales and other entertaining if vaguely abominable shenanigans, all part of a movie he was writing: Die Hard III.

Rewriting, actually. In January of the year of our despoiling lord Hensleigh, his spec buddy-action script, Simon Says, which had nothing to do with the Die Hard franchise, was bought by Fox, who then hired Hensleigh to convert it into a Die Hard movie, putting Bruce Willis’s John McClane back in the yippee-ki-yay business. Hensleigh, we learned—we coked-up, black-aproned transients who aspired to different shoes, shirts, and lives—had, just two years earlier, been a lawyer. But after seven itchy years, Hensleigh bankrolled his big bet: he wanted to be a screenwriter. So he quit, wrote two specs, sold them (we are to understand like that), and poof: the screenplays landed in the laps of Steven Spielberg (who hired Hensleigh, straight away, to write the best-forgotten A Far Off Place) and George Lucas (who hired Hensleigh, straight away, to write episodes of the best-forgotten The Young Indiana Jones Chronicles). Point being: guy quit law, banged out two specs, and within months was writing not for Hollywood but for hollywood. Two years into his new life, he sold Simon Says for a millionish dollars. And then he plopped down at my bar as he hyperbolized it into a Die Hard movie.

The fucker.

A reasonable person would have understood The Hensleigh Advent as a cautionary tale: sure, go for it little man, but do so with an understanding that the odds of experiencing similar success are a cool gazillion to one. Being an idiot, I liked those odds. With Hensleigh’s voice echoing through my ruminant brain, only one thought ricocheted: I, too, will sell a spec, one destined to become the next next Die Hard. All I had to do was write it, and the proverbial road would rise up to meet me—thanks to my connections.

If the images from the James Webb Space Telescope have taught us anything, it’s this: if you look deep into the darkness of the universe and consider what we estimate to be its two trillion galaxies and the trillions of solar systems they contain, it is statistically unthinkable that an uncountable number of these solar systems don’t harbor planets in the so-called Goldilocks zone, planets on which organic life flourishes, creatures of untold variety and splendor, creatures with one thing in common: they all have connections in Hollywood.

Here on Earth, everyone’s uncle’s brother’s barber’s kid’s girlfriend’s depressed cousin’s psychic’s personal trainer’s family friend is a gaffer or key grip in Hollywood, one who might be able to get your script to some factotum rowing in a minor production company’s development galley—the number of young people in Hollywood “working in development” exceeding the population of the great state of Maine—one of whom could (it was possible!) land you a meeting that could lead to a deal. These things happen! So of course I had a connection, mine turning out to be a little different, for as decades dragged on, my attempted exploitation of said person may be understood as the most humiliating face-plant in the history of nepotism.

When I was a kid, I was pen pals with the daughter of my New York parents’ closest California friends. Said pen pal’s older brother, was—I discovered on visits to Woodland Hills, California—cool. I tucked my Pittsburgh Steelers sweatshirts into my pants. Said pen pal’s older brother modeled. He drove a BMW. Coolest of all, he was also nice! Said cool/nice person went into the film business, bulldozing forward from intern to assistant to script reader to development drone—one who, thanks to bootstrap industry and perfect judgment, found a script in the slush that became a huge movie. One thing led to another until he was the huge thing, so much so that, at this writing, he’s arguably the most powerful person in film.

After my third year of college, in 1990, and after I’d taken a fiction workshop confirming my soul’s improvident hope that I Was a Writer, the nice but not yet absurdly powerful person, after I’d expressed an interest in writing movies, sent me a box of scripts. Like, twenty. Some were classic examples (Citizen Kane, Ordinary People, Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid), but most were movies in some stage of production, spanning various genres, all generated by talented young writers: Regarding Henry, by J. J. Abrams; Seven, by Andrew Kevin Walker; Quiz Show, by Paul Attanasio; The Last Boy Scout, by Shane Black. All the scripts were entertaining and instructive: having metabolized their methods and modes, the motivated student would need no further guide to the form. It was a four-ream-thick MFA.

Of that stack, Shane Black’s was the stick of dynamite in the box of Cohibas. Black was the only member of the bunch with a produced movie, Lethal Weapon (1987). A subsequent script, The Last Boy Scout, the expediter of the box explained, had sold for $1.75 million, more than any before it. It almost doesn’t pain me to say that reading it was one of the most exhilarating reading experiences I’ve ever had, up there with finishing William Gaddis’s The Recognitions, T. S. Eliot’s Four Quartets, Vladimir Nabokov’s Pnin, Ben Metcalf’s Against the Country, and—wait for it—Moby-Dick. You’ll have noted my qualificatory “almost.” My hesitation isn’t out of snobbery or shame; rather, a fear, in part, that you’ll recall the actual movie it became: an abominable R-rated travesty starring Bruce Willis, one which lacked, totally, the qualities of Black’s script.

If you read the thing now, the film’s failure to capture the narcotic thrill of the original makes perfect sense. As much as Black was a master of pacing, a fine crafter of set pieces, and delightfully de trop as a writer of snappy, manly dialogue, the most galvanic features manifested themselves in stage directions, interstitial material steering the reader through the gleeful nonsense. No context for this bonbon because who cares:

int. dingy dressing room—night

Cory and Jimmy are engaged in very hot sex. This is not a love scene; this is a sex scene.

Sigh. I’m not even going to attempt to write this quote-unquote “steamy” scene here, for several good reasons:

A) The things that I find steamy are none of your damn business, Jack, in addition to which—

B) The two actors involved will no doubt have wonderful, highly athletic ideas which manage to elude most fat-assed writers anyhow, and finally—

C) My mother reads this shit. So there.

(P.S.: I think we lost her back at the Jacuzzi blowjob scene.)

That’s the tenor of what keeps Black’s scenes taped together. Not that this idea—breaking the fourth wall of the script—was new. William Goldman, one of the greatest modern screenwriters, wrote charming, cajoling stage directions, addressing the reader directly, if passingly, with light touches of confederacy. Black cites Goldman as an influence, but Black’s version of the Goldmanic mode is on steroids. The reader is not cajoled so much as strong-armed into having the most delightful time: pigs in blankets appear just as the tummy grumbles; cheap champagne is sloppily topped off; cocaine, likely cut with creatine, is spooned into nostrils so that attention never lags. A reader of a Black script—first and foremost a reader-buyer—would feel giardia-level sick not to love it, so hospitable is it to the reader’s fat ass.

In the first ten pages of Boy Scout, a running back, heading upfield in a pro-football game, pulls a gun from under his jersey and, before sixty thousand witnesses, shoots the opposing players in his way. (“Pumps three shots into the free safety’s head. The bullets go straight through. On the back of his helmet. A mixture of blood and fiberglass.”) He makes it to the end zone, where he utters an appropriate witticism (“I’m going to Disneyland”), then blows his own head off. In the next scene, the drunk middle-aged hero (Willis) threatens to shoot a child with a .38 (a dead squirrel is involved), not long after which the reader reaches the “Jacuzzi blowjob scene” that Black’s mom probably didn’t like, wherein a jacked pro-baller repeatedly plunges a woman’s head underwater so that she might, against her will, perform aquatic fellatio. The script’s other hero saves the day by grabbing a football and throwing a sixty-mile-per-hour spiral at the attempted rapist’s face. But it was none of these particular instances of crudity that registered most with me on a sinking-feeling reread. Rather, it was the way that Black was, through his Virgilian shepherding of the reader through the carnage, ironizing the shit out of what has always been central to cinema: violence.

Since D. W. Griffith’s Intolerance (1916), the threat and depiction of grievous bodily harm has been no less a cinematic mainstay than marriage plots have been to the novel since Pamela (1740). Add realistic blood squibs to every western before 1960 and you have a live-action Alexander Gardner–directed talkie of “The Dead at Antietam” rather than a series of daffy tumbling routines. Psycho (1960) gave the ten-inch chef’s knife a best-supporting role, suggesting its potential without revealing its effects. After the name-says-it-all Blood Feast (1963), all modesty vanished and the armory diversified. We got suppurating puncture wounds in Halloween, hackings and cannibalizations in The Texas Chain Saw Massacre, zombie-you-name-it-ings in George Romero’s Dawn of the Dead, all of it presented not discreetly offstage but full-frontal at full throttle. Wild, vivid bloodletting, no one needs to be told, became de rigueur by 1970, licensing “realistic” maulings in “serious” cinema—let Sonny Corleone’s total perforation by machine gun in The Godfather serve as evidence. In B movies, horror and humor were made to co-exist in a particular way: black-comedic scenes shoehorned between shit-yourself-horror scenes were comic relief, release valves that deflated our jacked-up adrenals, readying us for another bullet to the brain.

But that’s not what’s going on with Black’s work. Because what most registered on my reread is that his stage directions chaperoning us to the narrative violence—bloody and cruel and misogynistic in the extreme—changed the tone of the genre.1

The laughter he generates in the margins isn’t the ha ha! the Achaeans release when Odysseus whops Thersites with Agamemnon’s scepter. It isn’t the dear god gasp that resolves to nervous and then impervious laughter in the Forum as lions and tigers gut slaves for supper. Nor is Black’s laughter machine a clear descendant of de Sade and his raping sprees. Black is not an imitator; he’s an innovator. He bred sadism with comedy and made a mode—Blackean sado-bathos. Not black humor: Black’s humor, a narrative method in which nothing is funnier than a head shot except two more and a couple of buddies to laugh about it.

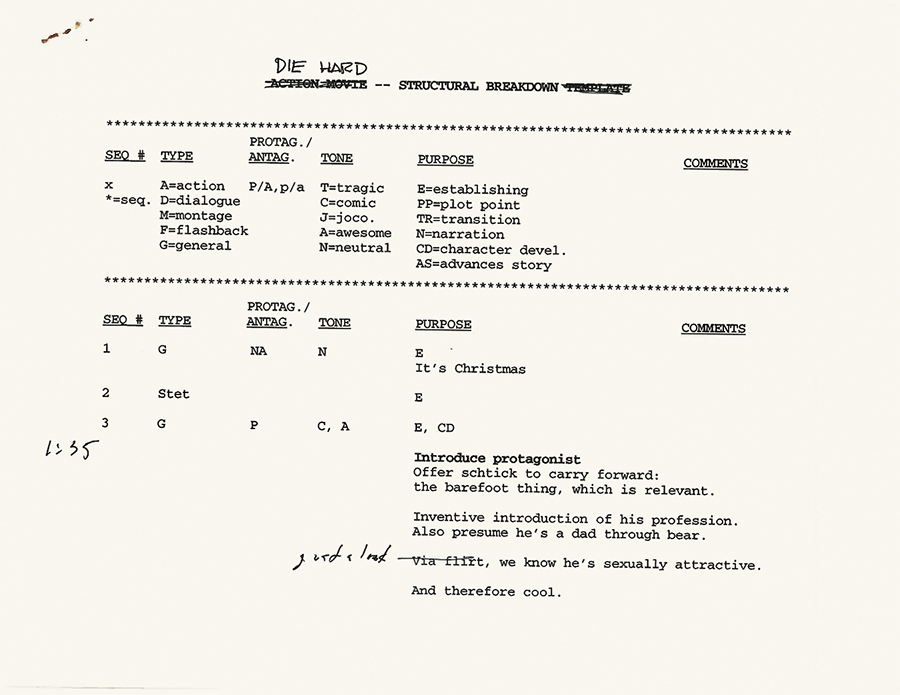

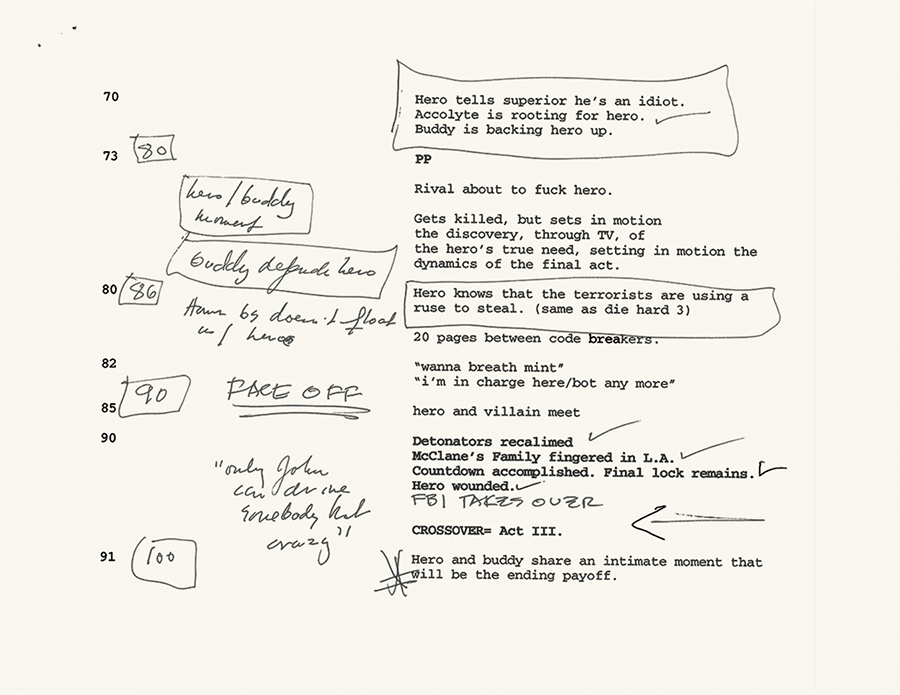

Between 1993 and 1998, I studied with great ardor the mechanics of these tremendous machines. A manila folder plucked from my archive of dead-or-done projects attests to my rigor. Contents include:

die hard action movie—structural breakdown template

die hard—simple structure

the rock—simple structure

the rock—structural breakdown

the last boy scout—simple structure

rules of the blockbuster actioner

Line by line, these documents show scholarly flair, insight, and animation. Taken as an aggregate, however, they are insane. Two pages should be sufficient to confirm a diagnosis—see for yourself in the images below.

Thus I studied; thus I learned; and after breaking it all down, I constructed my own constructions, my own Structural Breakdowns and Simple Structures that I amplified into Treatments and then, finally, Drafts, of many, many different scripts of my own. Shall I enumerate them here? There is neither time nor space to do them all justice. Suffice it to say, I churned away fruitlessly, feeling particularly miserable that I’d never come up with my own Die Hard idea. You’d think it would have been easier. There had been, after Die Hard, a blossoming of diehardean flora. Die Hard on a plane (Passenger 57, 1992); on a battleship (Under Siege, 1992); on a mountain (Cliffhanger, 1993); in a bus (Speed, 1994), and a dozen others, including The Rock (in a prison, 1996) and Con Air (on a prison plane, 1997), the last two, as if to mock me, both rewritten by Hensleigh.

Hensleigh!

One day, in 1998, a lightning bolt struck. I saw before me a marquee with my movie’s name blazing in the night: america unplugged. Along with a friend—who will go nameless here—we wrote the script with merciless speed and with my various structural schema before us. We also had at our disposal the spec draft of Simon Says to cheer us, a script both clear in its virtues and manifestly sub-Blackean; The Last Boy Scout was before us, too. The goal was to write something with a Die Hard structure that captured Black’s—not that we would have called it this; we were admirers—sado-bathos, all serving our million-dollar idea: Terrorists take down all the power grids in the United States during the State of the Union speech, creating a diversion for a giant heist: the theft of impressionist paintings from all the major American museums. Why impressionism? Ah. Because the terrorist in question, one Theo, was a great-grandson of Vincent van Gogh, his grandfather the son of the prostitute to whom Vincent gave the lobe of his ear and, counterfactually, a child. Terrorist Theo, who was—wait for it—crazy, and who, because he was the crazy bad guy, had a bad-guy accent (Dutch!), was going to destroy all the Monets and Cézannes and—you get the idea. And the idea was really to make $1.75 million dollars, about $1.74 million more than we were making. But it was also meant to serve as redemption for the lower-middle-class lives we were leading in the service industry, the furthest thing from that of action heroes.

I’d importuned now and again the increasingly powerful cool/nice brother who, by 1999, was president of a blue chip production company. I had met, along the way, a range of development drones, always girlfriends of friends, and they’d read and passed along my scripts, leading to conversations with mid-level execs. Said brother was importuned only occasionally, a distant wingman to these sorties. I was so inexplicably confident about my scripts that I assumed his help wouldn’t be needed. I think I was hoping to sell my stuff so I could stand next to him, cool at last.

Throughout my meteoric running in place, said fellow had offered support of a kind. He’d had his company’s script readers look at some of my stuff, so that I’d get a fair read (it pains me to say he was also honest), and reports came back as you’d expect. Of America Unplugged, he said that the idea had been in development for years in different forms and with different studios—i.e., scripts had been bought already about grids going down—so it hardly mattered whether mine was good or not.

At the end of the dying millennium, I went to L.A. to see a friend, to go camping in the desert as 1999 turned to 2000. During that trip, before we left for our camping expedition and the year faded to blank, at the end of a meteorologically ideal California day, I went to see said nice/honest brother, soon to be the biggest person in film. I had convinced myself it was a meeting, but of course it was a courtesy. His company’s office was the only one I’ll ever be in. Everyone was super nice, the office impressive but by no means swanky: pale wood, posters of movies produced, potted palms. I recall a lukewarm bottle of water received from a nail-bitten hand.

He will see you now.

In the nice man’s vast office, a chat.

How was his sister, how were his parents, how were mine.

Whereupon it was made continuingly clear that I’d have to do better.

He said this in the kindest possible way.

It was his last not-meeting of the day and we left together, standing briefly next to his Range Rover parked in his reserved spot. Before we parted, I had some sort of breakdown. At a certain moment, in an attempt to connect with said person in a familiar way, I put my hands on the broad shoulders of his nice suit. I placed them there hard enough that I pushed him backward—I insist a millimeter—into the Rover. I don’t know precisely what I said, but I do recall how he reacted. He looked down at my right hand on his left shoulder. He looked, over the top of his glasses, partway up at me. Then he smiled the smallest smile on human record, the smile of disbelief that a ladybug would think to pick a fight with a whale. Had he not known me since I was ten, I feel sure he would have decked me. But really, why hit someone who’d already professionalized the activity of beating himself down?

“Wyatt,” he said, “you need to put something of yourself in your scripts. They’re fine concepts. They’re structurally good. But it’s clear they don’t matter to you. Even in a high-concept movie, you need to bring something you care about. You need to write what you know.”

Of course he was right. But the problem was this: I had written what I knew. I just didn’t know anything.

So what was it that the screenwriters of Predator knew? The original script was by twenty-something brothers, Jim and John Thomas, who broke into the business when they sold their spec, Hunter, to Twentieth Century Fox in 1986. The studio hired them to revise it into the movie that became Predator, a title that crushes the original and seems to have been an eleventh-hour decision: a logo for the film had the original in place just months before the film’s release. Several versions of the script are online, one from the year it sold (1986), and one from when the movie was in post-production (1987), each a revision (or a re-re-re-re-revision) of the spec version, which I couldn’t track down.

Differences among them aside, they all offer no-nonsense thrills and, important to our mission here, no interstitial smirk, no winking on the sly, just tightly plotted mayhem and innovative gore, including this moment from the final script. Predatorphiles will appreciate appreciating it in prose:

The Hunter’s foot steps on the upper leg of the corpse, the prehensile spur digging deep, pinioning the body to the ground. The Hunter’s hand extends, his fingers puncturing the skin at the base of the spine, gripping the vertebrae.

With otherworldly strength the arm pulls, the entire spinal column ripping free from the body, a sickly snapping and popping of cartilage separating from bone and tissue.

Nice! Though I had good fun reading the scripts—noticing that they were a billion times better than anything I churned out—I couldn’t discern what of themselves the Thomas brothers had put into them (other than, say, talent). But it was very clear how different in tone these scripts are from Black’s: they play the mayhem straight, and you barely notice there’s a writer involved at all.2 You don’t think, reading them: Fuck me, this is going to make a great movie. The tension between the commandos, the tenderness in the violence—none of that is really there. You cannot imagine that a director would have read it and said: From these directives I shall paint my masterpiece. The lushness of McTiernan’s jungle, its intimate-to-the-point-of-erotic green, which ends up being so evocative that it wouldn’t be unfair to say that the movie is about a jungle importuned by rude guests: no one could have seen it coming.

I’m overstating it a smidge, but not much. Predator is a great movie, a great action movie. Meaning? Here’s the definition of “great action movie” that I’ve waited until now to deploy, given that it’s just so obvious: You’ll believe a man can fly. That, of course, was the tagline for Superman: The Movie (1978), the one with Christopher Reeve, and for you kiddos who’d yet to be imagined into being, it applies to the end of The Matrix (the first one, i.e., the only one), where Keanu Reeves soars from the floor of the digital city into our hearts.

No irony. Into our hearts: that’s where the belief in an action movie hits us, in our bodies, in the same way that a bassline by any epic rock band of my young adulthood or yours, heard live, does. It generates a feeling that makes, somehow, your heart grow three sizes in time for Christmas Day, so long as the fundamentally derivative thing moves from the mediocrity that imitation all but guarantees to something, somehow, good.

And these movies need to be good for the dudes who see them, not that I’m suggesting that action movies are only for dudes, except that I am suggesting that. They are meant to take the culturally and capitalistically and physically and sexually unempowered men of the world and fill their hearts with love, love of violence that might suggest how we’d feel if we stood a chance at lives that triumph over the limitations which, daily, make us feel like toads. The action movie is a testament to the ridiculousness of believing it should be otherwise; it is and has been a valentine shot—bang-bang!—into the rightfully broken heart of idiotic manhood.

Just before the pandemic, I was on a reporting trip that took me overseas. I was reading up on my subject, or trying to, distracted by the shock wave of screens that were mounted behind every seat and infringing on my industry. I was in an aisle seat, and a little girl, around six, sat across from me. She was reading her Beezus and Ramona, a picture of innocence. Her dad—it became clear—was sitting in front of her, while she was sitting with her younger sibling and their mom. A couple of times she tried to get her dad’s attention. He was deep into a movie playing on the back of the seat. At a certain point, I saw her sort of gasp in my peripheral vision. I looked at her and saw that she was peering at her dad’s screen. On it, the beautiful and transcendent Keanu was, very slowly, forcing a dagger into the eye of a man. He was halfway there, but it still seemed like another five minutes before he completed his careful work. The girl watched it all, sat back, and burst into tears.

It was from one of the John Wick movies, I came to know, films I’d not seen. In the years since my misguided screenwriting quest, I have kept only a toe in the action genre. The Missions Impossible, the James Bonds, the skip-ahead-to-Adam-Driver Star Wars sequels. Ninety-five percent of the time, these are as bloodless as Forties westerns, mostly people elaborately falling down, snazzy set pieces, stuff of the You will believe a . . ., Tom Cruise his own five-foot-seven special effect. But nothing I’ve watched has been of the Blackean Strain, no laughing after someone is cut in half. I think part of this has to do with the inevitability, as one ages, of seeing violence enter one’s life. Someone getting hit by a bus just isn’t that funny anymore.

So there are holes in my bellicose literacy, and I felt I needed to see that objectionable dagger-in-the-eye scene in context. I watched all three of the John Wicks in order, avoided when they came out because they just seemed too violent for me. As I expect will not surprise you, I found those five hours and fifty-three journalistically mandated minutes to be disturbing. You’re an American, you know the plot: Keanu’s puppy, a post-mortem gift from his forethinking dead wife, is murdered by the Russian mob. Keanu, a retired hit man (he retired for his wife), kills the mobsters, unleashing a revenge spiral that puts a price on Keanu’s lovely head, up to $15,000,000 by the third movie, every hit person in the world after him. And so Keanu kills them all. The internet says 299 to date. Most are face-kills, close-range combat where Keanu shoots his attackers—they’ve come for him!—in the face.

The tone is light, the story basically picaresque. The tone isn’t Shane Black, not exactly. It isn’t glib or ironized, and yet it is a clear descendant of his ethos. There are jokes. The finale’s fight with the ninja-in-chief, delicious in its complexity, ends with Keanu impaling said ninja, who, in his death throes, the hilt of Keanu’s sword in his sternum and the blade sticking a foot out of his back, says, “Hey, John. That was a pretty good fight, huh?” before keeling over. It doesn’t feel like Black, though. It’s—weird word—sweeter. Funny too, because the movie is the most violent thing I’ve ever seen. Heads explode, Keanu often shooting the same head two or three times for good measure. Keanu will fall from three-story buildings, land on his head, and get up with a limp. We’re in the realm of live-action Bugs Bunny / Road Runner, if Road Runner were strapped with an AK and in a $10,000 bespoke suit.

But that knife-in-the-eye scene—an artisanal face-kill—is in Chapter 3: Parabellum. It concludes a jaw-dropper of a martial-arts fight that unfolds along a glass-display-case-lined hallway, multiple attackers trying to perforate Keanu, who, taking one weapon after another from the broken cases—swords and small daggers—mangles every one of those very agile dudes. Just thinking about that sequence makes me feel strange things. Not the horror of eye-murder as entertainment or the sorrow of seeing a child discover that our culture is barbaric. No, the uncomfortable feeling I have just thinking about it and the whole John Wick killorama is, unfortunately, a feeling adjacent to the one I have when I watch my son pick an apple from a tree in an orchard and see him beam with dwarf pride. It’s totally fucked up, but I’m unfortunately sure it’s joy—the joy of being alive.

That’s, on reflection, what disturbed me most in Parabellum: the joy. So much balletic gorgeousness and physical wit, movement that Chaplin or Keaton or Nureyev would have, sure as shit, admired, fills the frames. The assault of that joy is tireless, growing more astounding not through repetition but through variation on a murderous theme. So when, at the end of the hallway of carnage, Keanu’s dagger tip pierces his combatant’s pupil and iris and sclera and conjunctiva and pushes past the retina and into the brain, all motion ceasing, I did what, I am certain, any reasonable person would do: I burst into laughter, gut-heaving, grand mal laughter. Not because it’s funny. Fuck no. It’s disgusting. What produced it wasn’t violence. It wasn’t irony. It was beauty, the beauty of human bodies in glorious motion, put in motion by writers writing about what they have known since Seneca said it first: to write action movies is to prepare to die—and to help us manage those preparations as well.

The little girl who burst into tears didn’t know that. It was a rude awakening, and ill-timed, but there it was. She witnessed human beings doing what human beings try to do: We try not to die. And, as she already understood, it doesn’t end well.