Falling Like Leaves

Amhara militia members in Lalibela, January 2022 © Eduardo Soteras/AFP/Getty Images

Late last March, just after five o’clock in the evening, I stood on a dusty ball field in the town of Lalibela, Ethiopia, in the state of Amhara. Beyond the tall trees at the parcel’s western edge were green mountains and a long valley that descended seemingly without end. To the east, a dirt bluff rose high above the field. A hilly, quarter-hour walk to the southwest was the Church of St. George, one of the town’s famous twelfth- and thirteenth-century stone-hewn temples, where during these days of Lent the voices of children singing reverberated against the red rock of the sanctuary.

About two hundred civilians of all ages—mostly men, and a handful of women—were gathered here for combat training. One group, of around a hundred people organized into rows, was taking turns marching with precision, stepping and pivoting on command. Trainers, distinguished by bits of camouflage clothing, led them in a chant: “Amhara! Ethiopia! Fighting for freedom!”

Other trainees huddled around woven mats laid on the dry dirt. Instructors each balanced on one knee, hovering over the ground as they assembled and disassembled Kalashnikov rifles. Trainees took turns attempting the task, dropping to their mats and fumbling with the guns’ dust covers and recoil springs. Periodically, someone chased away the children who had gathered to watch. Nearby, three men passed around a green grenade, its striker and pin removed. One handed it to me and pantomimed how the serrated, cast-iron shell would break apart when it was live and thrown.

The trainers were members of Fano, a long-standing militia of Amhara people, one of the largest ethnic groups in Ethiopia, which had ruled the country almost continuously from the late nineteenth century until the defeat of the last emperor, in 1974. Thirty miles to the north of where we stood was the border with the state of Tigray, the northernmost region of the country, where a war had been raging for the past year and a half. The Ethiopian army, called the National Defense Force (ENDF); the Eritrean army; Fano; and Amhara Special Forces had invaded the state in early November 2020, under the direction of the Ethiopian prime minister Abiy Ahmed, purportedly to quash a rebellion of the Tigray People’s Liberation Front (TPLF), the state’s dominant political force. With Abiy’s tacit approval, Fano had worked in tandem with the other allied forces to retake territories in Tigray that Amharas claimed were rightfully their own. The TPLF fought back, and by July 2021 forces under their command had outflanked the federal troops and their allies and pushed south into Amhara, as well as into Afar, a state to the east. Roughly two hundred and fifty thousand people fled as the war broke beyond Tigray’s borders.

In early August, the TPLF took Lalibela—by many accounts without a fight, though locals say that several residents were killed. Amhara Special Forces, in the town to protect its citizens, withdrew before the Tigrayans arrived, taking five of the city’s ambulances with them. Hundreds of residents ran, escaping to the neighboring forests and mountains, some to join forces preparing a counterattack.

The TPLF held Lalibela for nearly five months before retreating at the end of December. The occupation was less deadly than those in other villages and cities overtaken by the Tigrayan troops: thousands died throughout the state, while only a handful of killings were documented in Lalibela. Many residents believed that this was thanks to the churches, where Tigrayan soldiers had been seen lowering their guns and entering to pray. But TPLF troops raped many Amhara women in Lalibela, and vast numbers throughout the region as their lines advanced.

Some of the trainees on the dusty field would join Fano, but many more had come to learn to protect themselves and their families if the Tigrayans returned, which they believed was inevitable. There was no small talk or milling about. The trainees awaiting their turn to march sat in a long quiet row, their shirts a colorful ribbon against the gray mountains.

I had come to the training with Fentaw Asnake, whom I’d met early that morning at the Blue Nile Guest House café with my guide Mario, whose full name is Misgan Assefa. We drank coffee on the back balcony overlooking the corrugated aluminum roofs in the valley before us. Fentaw and Mario were longtime acquaintances, and when Fentaw said that he was now Fano, it was a brag. While no independent militias were allowed in Ethiopia, Fano’s existence had been an open secret for years. As tensions with Tigray had grown and the war approached, the government had given the militia special ID cards and permission to carry weapons. “We are in the open now,” Fentaw said.

At the training, Fentaw led a man named Menber Alum over to speak to me. Menber wore a green headscarf common to the region and had a rifle slung over his left shoulder. He’d been chosen as a spokesman for the group because of his clear English, but he was also a performer, by turns fierce and placating, more interested in selling me on Fano’s purpose than in answering questions. The Amhara were always under attack, he said, a persecuted majority. Though ethnic Tigrayans make up only 6 percent of the country’s population, the TPLF had controlled the Ethiopian government for the thirty years preceding Abiy’s election in 2018. The Tigrayans had been oppressive rulers, Menber said, and the Amhara had borne the brunt of their aggression for too long. Though the TPLF had been pushed back from Lalibela, the war here was not at all over. He pointed to a mountain range in the distance, land in the Raya district, some of which had decades ago belonged to the Amhara, but which had been absorbed into Tigray under TPLF rule. It was now, for the moment, Amhara territory once again. But TPLF troops were still there in the mountains, he told me. “Maybe fifty kilometers in this direction we will get them,” he said. “They might attack at any time. We have to stay ready.”

The Amharas only wanted peace, Menber said—a common refrain, I would learn. But that peace would come at a cost. There were crimes to be punished. Did I believe, he asked, that the rapes committed by Tigrayan soldiers in Lalibela were cause for retribution? Did I understand that Fano would be seeking revenge? He asked me to imagine that the victims included my mother, my sister. “Do you think it is fair?” he asked. “What do you think? What do you feel?” He pinched the fingers of his left hand together and shook them back and forth between us, drawing a tether.

The civil war that followed the invasion of Tigray lasted two years and formally ended with a tenuous peace agreement in early November, marking a defeat for the TPLF and placing control of Tigray in the hands of the federal forces and their allies. Whether this accord will hold is yet to be seen. To date, the war is believed to have killed at least half a million people, including somewhere between 385,000 and 600,000 civilians—through violence, starvation, and other deprivation—and has displaced more than five million. By conservative estimates, it is one of the deadliest conflicts fought in the past thirty years—as deadly as those in Darfur, Afghanistan, Iraq, Yemen, and Crimea combined.

The facts of the war have been clouded from the start, heavily disputed by both sides, and occluded in great part by a communications blackout in Tigray, where the majority of the violence has taken place.

Late at night on November 3, 2020, after three months of what would become an eleven-month delay of the national election that was to determine whether Abiy would remain in power, the TPLF—political opponents of Abiy—attacked multiple ENDF command bases in Tigray. The federal government shut down the internet in Tigray at 1 am the next morning and cut electricity and cell service soon after. Fighting began that day.

While the TPLF claimed that their strike was preemptive—a response to ENDF plans to arrive in Tigray and to troops already amassing on the southern border of the state, as Eritrean soldiers gathered along the northern—the government claimed that the invasion was a “law enforcement operation” provoked by the TPLF attack, and declared a six-month state of emergency in Tigray, formalizing the blackout and blockading routes in and out of the region. Those roads remained closed for the duration of the war, thwarting most humanitarian aid and keeping out reporters. By the spring of 2021, the federal administration had begun deporting international journalists from the rest of the country.

Yet the brutality of the conflict, characterized by violence against civilians, has been clear. The majority of such attacks seem to have been committed by federal troops and their allies against Tigrayans, and the information escaping the northern province has been sufficient for international agencies and the United States to allege war crimes. In March 2021, Secretary of State Antony Blinken stated that killings in Tigray—particularly in the contested territory known as Western Tigray—amounted to ethnic cleansing. According to Ghent University, which has relied on informants in the closed state, nearly three hundred massacres or group killings of civilians have taken place in the province since the start of the war. Though it’s unclear what role the federal government has played in these assaults, Abiy has long used dehumanizing language to describe the TPLF, calling them a “cancer” and “weeds.”

However, not all of the crimes in Tigray have been perpetrated against Tigrayans, nor by the federal allies, and the violence carried out by both sides has spread far beyond the state’s borders. There is in fact reasonable question as to which side of the war began the mass murders of Ethiopians: the first known massacre of the conflict, five days after the invasion, was committed by the TPLF against Amhara civilians. And the TPLF has directly retaliated for attacks on Tigrayans with assaults on Amharas. When Fano murdered between twenty-five and twenty-nine Tigrayans on October 29, 2021, in Dessie, a town about sixty miles south of Lalibela, TPLF forces arrived two days later, to nearby Kombolcha, a town with an almost entirely Amhara population, and killed one hundred people. To date, at least eighty-nine incidents of civilian group killings have been documented in Amhara, Afar, and Benishangul-Gumuz, a region in the country’s west.

It has been widely reported that rape has been used as a weapon of war in Tigray: in August 2021, Amnesty International found that the ENDF and their allies had subjected “Tigrayan women and girls to rape, gang rape, sexual slavery, sexual mutilation and other forms of torture, often using ethnic slurs and death threats.” The TPLF troops are guilty of much of the same. Another Amnesty report, released last February, described the Tigrayan army’s use of rape as a war crime and concluded that their actions, based on “the nature, scale, and gravity of the violations committed,” may also “amount to crimes against humanity.”

The question of ultimate blame is not one I will or can answer here. What I am able to report is radically incomplete. I went to Ethiopia to try to bear witness to the widely decried atrocities in Tigray, but I was not able to enter the state. And all around me, in Amhara, were the scars of the TPLF’s violence—a story far less known, and in its individual assaults, no less brutal. It may be revealed in the coming months and years that the allied crimes against Tigrayans are far greater in scale, or far more horrific, than we now know, surpassing those of the TPLF to such a degree that the latter may seem minor. It is further possible that yet a greater cost of peace will now be exacted by the enemies of the Tigrayans. As I write, Eritrean and Amhara regional forces and militias still occupy the northern province, and government officials have stated that these troops will not be made to leave until the TPLF has fully demilitarized, as it has promised to do. Meanwhile, Abiy has not seemed interested in lowering the temperature. Speaking to a crowd shortly after the peace agreement, he called on the Tigrayan people to acquiesce, saying, “Tricks, evilness, and sabotage should stop here.”

Yet what is laid bare in the future will not erase the reality of what has happened to individual Ethiopians, including non-Tigrayans. Whatever we may learn, their lives and stories matter.

A map of Ethiopia from 2019 © Rainer Lesniewski/iStock

I arrived in Ethiopia in March, when the jacaranda trees were in bloom, and flew to Lalibela with Mario, who was born and raised in the town and had not been back since the war began. The Lalibela airport had been ransacked by the Tigrayan troops; rooms off the main thoroughfare were filled with broken furniture and smashed security scanners. The town itself, a sprawling enclave at roughly eight thousand feet above sea level, stretched along hills and valleys, was still without electricity, though the occupation had ended three months before. Women and girls carried water for miles from tankers and meager springs, and they could be seen along the town’s footpaths and cobblestone streets, yellow jerricans tied across their shoulders with rope.

Mario and I stayed at the Maribela Hotel, where we were the only guests. The staff switched on a generator briefly each morning and evening to cook; at all other times we relied on flashlights and candles. The window in my room, facing west, framed the mountains that stood between the town and Lake Tana, the source of the Blue Nile. The first night the sky was full of stars. Just down the road another hotel sat in ruins, charred by an ENDF drone strike that had been used to flush out TPLF commanders. In peaceful times, nearly eight thousand tourists had visited Lalibela each month; now they were only a handful.

In the morning, we woke early and set out to find coffee, but the cool air and the bustle on the town’s hillside paths were inviting, and we kept walking. Women traveling to the market carried pots of honey and large bundles of wood; some led donkeys burdened with vegetables and sacks of salt, corn, and spices. My presence was again and again greeted as a good sign: foreigners were returning to Lalibela.

Mario and I set our sights on the town’s tallest mountain, capped with a partially constructed hotel, the Mekane Lielt, meaning “the place of the king and queen.” King Lalibela, who reigned over the region from 1181 to 1221 and is credited with building the stone churches, was said to have lived there in a modest tent with his wife, and the spot was considered sacred. Locals had opposed the hotel, and the project was halted years ago.

At the compound’s open gate, an elderly guard in a wide-brimmed plaid hat rose to greet us. Inside was a cobblestone courtyard, encircled by freestanding bungalows, a bar, and a small, empty store. The guard walked us along the interior perimeter, pointing to broken doors, overturned beds, a black ring scorched into the ground. This was the work of the TPLF troops.

The guard told us that sharpshooters had kept watch from the hotel’s roof during the occupation. The Tigrayan soldiers had ordered Lalibelans to remain inside. He pointed to a nearby bluff, where he and his extended family lived, and where they’d stayed during those five months, relying on the forests and few hills that obstructed the troops’ sights. Animals that weren’t kept inside were shot, he said, and many residents lost livestock.

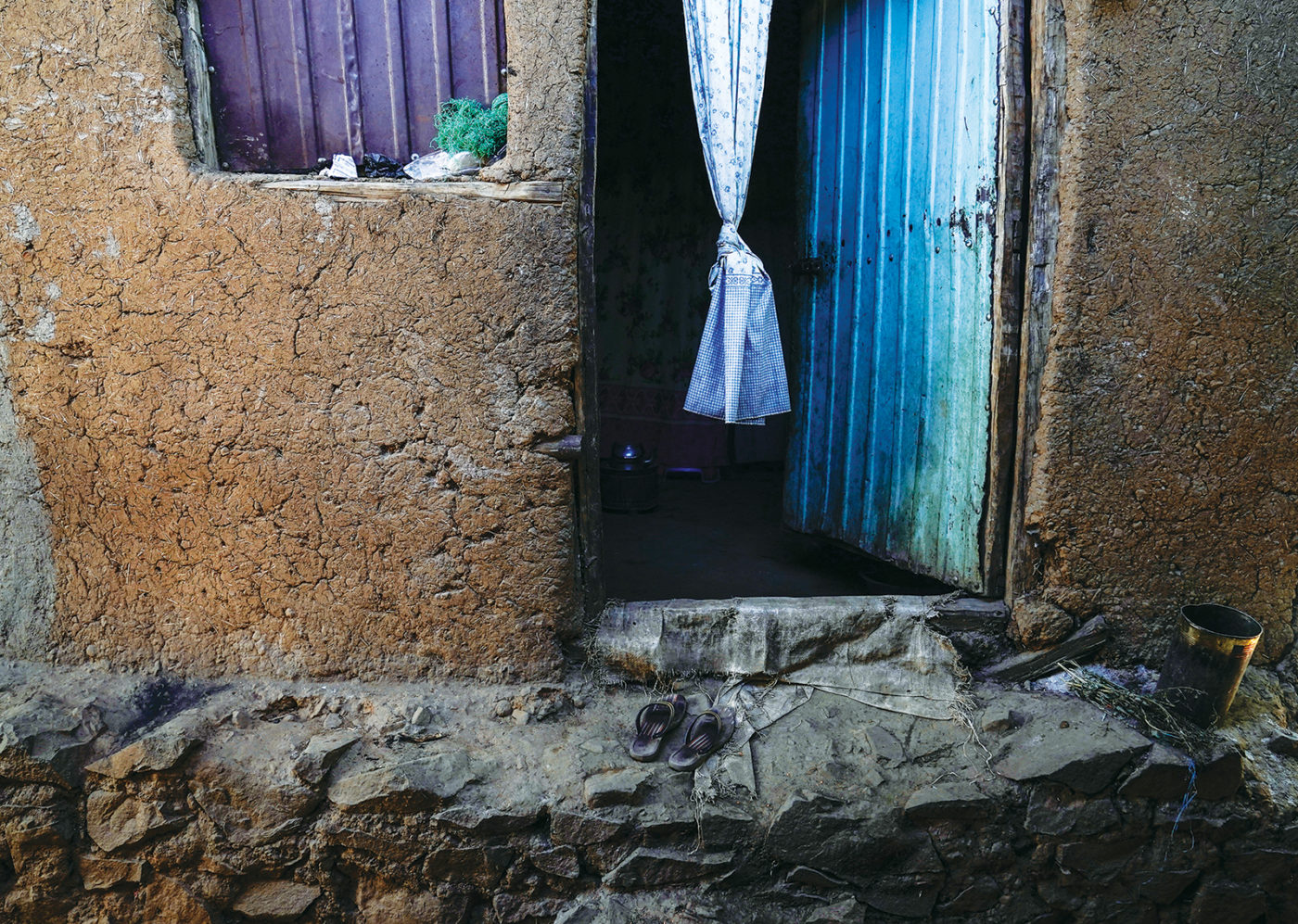

The day before, I had visited Mario’s family home, and met with his mother, father, and one of his sisters, who’d also stayed inside for the majority of the five-month siege. Mario’s father was wearing a removable coat hood to address a cold and pain in his ear. The Tigrayans had looted the town’s medical supplies, they said. Fano and Amhara Special Forces had managed to push the TPLF troops out of Lalibela for a short time in December—eleven days—before they returned and regained control. During that second occupation, Mario’s mother said, the soldiers had been more violent, beating residents who were unable to feed them.

The guard said that he’d heard that the TPLF were animals, driven by bloodlust, as I would be told repeatedly. He led us up the broad steps of the hotel’s main building to the roof, where the sky opened up. The soldiers would have been able to see the whole countryside, laid out before them in all directions.

Ethiopia has long been seen internationally as exceptional, marked until recently by its relative prosperity in Africa and by an idea of its unique constancy, based on the country’s resistance to colonial rule by Europeans and on its millennium of Christianity, revered by the West. But the terrain making up Ethiopia has been subject to territorial clashes for hundreds of years, and the ethnic hostilities powering the current war have simmered for much of the country’s modern history.

Disputes between the Tigrayans and Amharas trace back to the eighteenth century. At the turn of the nineteenth century, the Amhara emperor Menelik II forcibly unified what we now consider Ethiopia by annexing the domains of more than eighty ethnicities, including the sovereign kingdom of Tigray. Emperor Haile Selassie, also Amhara, who reigned from 1930 to 1974 (excepting a brief interregnum when the country was occupied by Mussolini’s army), attempted to centralize authority and granted formerly Tigrayan land—including the fertile and strategically important territories now called Western Tigray—to the Amhara. Tigrayans, who had ruled the region for centuries, revolted, and the uprising was put down with the help of the British Royal Air Force. Selassie’s retribution was brutal: his army burned villages and massacred civilians, and the region was mired in poverty for decades.

The TPLF arose in the Seventies as a Marxist movement opposing the Derg, a violent, Soviet-backed junta that had overthrown Selassie. The TPLF promised peace and democracy, including autonomy for each of the country’s ethnic groups, and led a coalition of guerrilla forces known as the Ethiopian People’s Revolutionary Democratic Front (EPRDF), which finally defeated the Derg in 1991. The EPRDF was made up of pro-democracy parties from Tigray, Amhara, Oromo, and one representing more than fifty ethnic groups from the southern states, but it was dominated by the TPLF and headed by a Tigrayan, Meles Zenawi, who became prime minister of the new Ethiopia.

The TPLF, under the guise of the coalition, oversaw widespread economic growth. But the minority Tigrayans ruled unilaterally, and established a constitution that divided Ethiopia into eleven states based on regional ethnicity. As land was redistributed, the Oromo, the largest group, making up around 35 percent of the population, maintained the vast state of Oromia, in central and southern Ethiopia. The Amharas, the second-largest group, at roughly 27 percent, lost significant territory to the state of Tigray, including the Welkait, Kafta Humera, and Tsegede—much of the same land that had changed hands under Selassie—displacing thousands.

The TPLF grew increasingly authoritarian over the next two decades, and nationwide protests against the regime overtook Addis Ababa and other major cities in 2005 and again in 2015. The federal government responded with severe crackdowns in both instances, killing hundreds of civilians. In February 2018, the then prime minister, Hailemariam Desalegn, resigned, and members of the EPRDF jockeyed to appoint his successor as massive demonstrations continued.

Finally, the Amhara and Oromo parties secured Abiy as the new prime minister, effectively ending the Tigrayan regime. The excitement that Abiy’s appointment brought to the country is hard to overstate. Abiy, who was both Oromo and Amhara by birth, and had fought in the revolution against the Derg, took on the role of unifier, presenting himself as a newcomer though he’d worked in the TPLF government, and promising democratic freedom, ethnic representation, and prosperity. Early in his first term, he released the previous administration’s political foes from prison, including journalists; declared the country’s press free; and brought greater ethnic diversity into the government. He also did what had seemed impossible: forging peace with Eritrea, which had become an overt enemy of Ethiopia during the prior thirty years. Eritreans had aided the EPRDF in overthrowing the Derg, an effort for which the small country to the north had gained its independence from Ethiopia. But in the years following this alliance, the long border between the two—at the northern edge of Tigray—was never fully delineated, and land disputes had resulted in a deadly war and ongoing skirmishes. For the new accord, signed by Eritrea’s Isaias Afwerki, Abiy received the Nobel Peace Prize.

The morning after our visit to the Mekane Leilt, as I brushed my teeth in the dark of the Maribela bathroom, a group of Fano trainees ran by the hotel chanting the same words I’d heard at the ball field: “Amhara! Ethiopia! Fighting for freedom!”

Mario and I hired a van and headed out on the deeply rutted road to the nearby village of Gellesot, which, like Lalibela, had been occupied for five months. Fentaw accompanied us and flashed his Fano ID at government checkpoints. In Gellesot, it was market day, and crowded. Young men wore shirts with button-adorned swatches sewn onto the tails and sleeves—details that would catch the eye when they danced the eskista, shaking their shoulders.

Fentaw led us down a dirt road to a tukul—a rounded stick-and-mud home—where we met Misaye Kassa, a tall Amhara woman and a domestic worker, around forty years old. Inside, her son, about nine, was ill and lying under a sack on a stone-and-mud sleeping platform.

We had come to learn about a particular night of the occupation, and Misaye remembered it precisely. “It was on the feast day of Gabriel,” she said, October 29. A group of Tigrayan soldiers had arrived in the afternoon, after she’d prepared the jebena—the long-necked clay pot Ethiopians use for coffee—and put it on the fire. They told her to slay two chickens for them to eat, but she refused, saying they could kill her instead. They fired a warning shot over the house and left.

After dark, one soldier returned. He aimed his rifle at Misaye’s son, and she understood what he was there for. “Take care of it with me,” she told him. He beat her with a stick—she showed me her misshapen left hand—and then raped her. “What can be done?” she said. “I called for my kinsmen. No one came. Now whenever I come and go, they say, ‘There’s the wife of the Tigrayan.’ ” Local boys had crowded around the doorway of her home while we spoke. When I asked Mario and Fentaw to shoo them away, Fentaw shrugged and said that she was used to it.

The next morning, I met with Eshetu Shimels, a young doctor in Lalibela, who took me to see a woman with a strikingly similar story. At a small tukul, the woman, Sefi Emagn, greeted us at the door but looked only at Eshetu. They’d met at a local clinic. She was twenty-three, a washerwoman, and wore a black long-sleeved blouse and a red skirt printed with peonies. Inside, her baby son slept on a thin mattress on the floor.

On the evening of December 14, two TPLF soldiers had appeared in the dirt courtyard behind her home as she walked across it with her son. She shouted and one cocked his gun and pointed it at the baby. She tried to call to a neighbor, a woman who lived with her children. “Are you screaming to get them massacred?” the soldier asked, laughing. He brought Sefi inside and raped her while the second soldier waited on the road.

“Afterward, what can I do?” she said. She began to cry. She was concerned that she might have contracted HIV and had gotten tested at a nearby clinic. She would need to wait three months for the results. Eshetu tried to comfort her, saying that she could live with the virus. “It’s my son that’s giving me trouble,” she said. She was afraid to nurse him. Eshetu told her to feed the boy sugar water for now.

Later in my trip, I’d meet with Demeke Desta, the Ethiopia director for Ipas, a group that advocates for women’s health services. Demeke told me that in recent months women throughout the war-torn regions of the country had fled their towns after being sexually assaulted by soldiers from both sides of the conflict. He said that some had joined Orthodox monasteries. Others had committed suicide.

In the last days of March, I returned to Addis Ababa, and walked to the newly designed Unity Park, a project of Abiy’s that opened in 2019, where a series of structures represented each of the Ethiopian states: a wooden replica of the Church of St. George for Amhara; models of the carved stone monuments and stelae of the first-century Kingdom of Axum, the birthplace of Ethiopian Christianity, for Tigray.

The park was intended to portray a harmonious Ethiopia—one that had never existed and certainly did not exist now. Following the peace accord with Eritrea, hopes for Abiy’s tenure had quickly dissipated. In 2019, national demonstrations protesting the slow rate of various reforms were met with mass arrests and violence, including the burning of civilian crops and homes.

Despite his image as unifier, Abiy had, in the words of the New York Times, “suffered numerous humiliations” as a non-Tigrayan in the TPLF government, and he deeply resented the northern leaders. In December 2021, the Times reported that, according to government officials, Abiy had been planning the invasion of Tigray with Eritrea’s Isaias since the peace agreement in 2018, in a pact that would serve the grudges of both men. Isaias, for his part, blamed the TPLF for the war between the two countries.

Leaving Unity Park, I walked west to Taitu Street, where cars approaching the gates of a Sheraton were stopped and searched by young men in pith helmets employing mirrors on long handles. Across from the hotel was Sheger Park Friendship Square, another new project. In 2019, when I’d last visited Addis Ababa, this hillside had been covered in trash and campfires. Now, pink geraniums tumbled down the slope, and fountains hissed in ponds. At the park’s focal point, a view of the city skyline and its reflection in Sheger Lake, I stood on a dais in the shape of a calla lily, the national flower. According to a plaque nearby, the lily symbolized “the country’s national solidarity.” The government was represented by a red granite center and darker stone in the shape of two eyes.

The next day, I met with a man whom I’ll call Yohannes, the only Tigrayan who agreed to speak with me while I was in Ethiopia, in the lounge of the Hilton Hotel. Outside, Ethiopian travelers dipped into a pool in the shape of a crux quadrata, the footprint of Lalibela’s Church of St. George. Yohannes and his wife were arrested in November 2021, when the Abiy administration detained thousands of ethnic Tigrayans in the capital under the pretext that they could be TPLF sympathizers. They’d been picked up in the night at their home and transported to a former chicken-processing plant in the northeast of the city, where they were held with 650 other Tigrayans for 51 days.

Whatever crimes the TPLF had committed, Yohannes told me, it would soon become clear that the horrors inflicted on Tigrayans were far worse. “This is a game,” he said. “What you don’t understand is, at the moment they are buying more time so people can die.”

On my way to Ethiopia, earlier that month, I’d stopped in Cairo, where I met an Amhara man named Tesfahun Assfa in a restaurant in the narrow streets of the Ard el-Lewa neighborhood. Tesfahun, who is about forty years old, had witnessed what is believed to be the first massacre of the war. He was in Ethiopia by chance when the conflict began, in Humera, the town in Western Tigray where he grew up, in the long-contested Welkait. He’d left Ethiopia for Sudan in 2012, after years of intense harassment from Tigrayans who wanted Amharas gone from the territory. In 2020, after entering Egypt illegally during an attempt to leave Africa, Tesfahun was arrested and deported to Ethiopia, and made his way back to Humera hitchhiking and on foot.

The war started just a few weeks later. Five days after the invasion of Tigray, Fano and Amhara Special Forces traveled through Humera from the south and relayed that there had been a massacre in Mai Kadra, a small town to the southwest, where Tesfahun’s uncle lived. Tesfahun and a handful of others rode a tractor the fifteen-mile distance, and as they entered the town, found hundreds of corpses lining the road, some covered with branches. It had been less than twenty-four hours since the killings.

“The TPLF slaughtered one thousand five hundred people with knives,” Tesfahun said. Accounts of the killing vary, but his story is roughly consistent with reports from Reuters, the New York Times, Amnesty International, and others, which have found that Tigrayan soldiers murdered between 500 and 1,650 Amharas before fleeing incoming federal forces.

“Some of them were cut this way,” Tesfahun told me, as he brought his hand down on the back of his neck like the blade of a machete. “The rest were cut this way”—he chopped at his throat. “There were children among them,” he said, “women who were slaughtered along with their husbands.” He was able to find his uncle, alive, and then helped to bury the bodies, including those of ten of his former classmates.

The ENDF and Fano arrived in Mai Kadra the next day, where, according to the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights, they killed at least five Tigrayans in retribution. Multiple reports say that the bulk of their retaliation took place soon after, in Humera, where they are believed to have killed two hundred and fifty Tigrayans. Tesfahun denied these accounts. Their purpose, he said, was to “defame Amhara.”

According to Tesfahun, Tigrayans in Humera fled to Sudan, and Amharas took up residence in their homes. “There was no police, no law,” he said. Amhara Special Forces told him that if he stayed he would need to defend the land and gave him a rifle. “I didn’t want to do it,” he said. “After suffering all those years, what is the point of holding a gun now?”

Tesfahun denounced both sides of the war. Abiy’s reign, he believed, was worse than the TPLF’s had been. “Under this regime,” he said, “people are falling like leaves.”

On my final day in Ethiopia, I walked to the federal ministry of education, an imperial-era building that curves around a portion of Arat Kilo circle, to meet with Berhanu Nega, the minister of the department and a former leader of a radical party that had pushed for democracy during the TPLF’s time in power. Because the federal government had continued to deport international journalists, I’d waited until the end of my stay in the country to contact Berhanu. The violence of the TPLF was clear, but I intended to press the former rebel on the reality of attacks on Tigrayans, and the administration’s role.

In the years before Abiy’s tenure, Berhanu, who is Gurage, an ethnic group that makes up less than 3 percent of the population, had twice been imprisoned for speaking out against ruling regimes and twice fled to the United States—once, in 2005, when he was the mayor-elect of Addis Ababa. In 2009, he and four others were sentenced to death in absentia for the alleged crime of plotting a coup d’état. When Abiy was appointed prime minister, he called Berhanu and other dissidents to Addis Ababa for talks. “Our interest was,” Berhanu told me, “Are you committed to democratic politics? Eventually, if not immediately?” He was convinced by Abiy’s assurances, and still believes the prime minister is the most democratically inclined leader the country has had. “I’m not saying that he’s perfect,” he said, “but he’s much more enlightened. He’s much more aware that this is not a country that can be controlled by force.” The irony of his words—that Abiy had launched a catastrophic civil war, under way as we spoke—could not realistically have been lost on him, but he held firm. When I raised the fact that Tigrayans had been detained and journalists deported, he said that “certain forms of free speech” had been threatening the stability of the country. The international media, for example, were presenting the war as if it were Abiy’s fault, and as if the Tigrayans were simply victims. “And that there is going to be genocide perpetrated,” he went on. “We have to stop that kind of stupidity.”

Was it stupidity to admit that Tigrayans had most certainly been massacred by allied forces, or that millions of people in the northern state were starving? Federal troops had slashed crops, dammed supply lines, and blocked USAID and others from delivering food. Berhanu acknowledged that violent atrocities had taken place and said that these events should be “accounted for”; he claimed that among the federal forces and their allies, “something like sixty” officers were currently being tried for crimes against civilians. Indeed, in the spring of 2021, the government had stated that four federal soldiers had been convicted of raping and killing Tigrayans and that another fifty-three faced similar charges. Berhanu claimed that not one TPLF soldier had been thus held to account.

According to Berhanu, the Tigrayans had intentionally instigated the war because they knew that they could not maintain their territory under plans Abiy had for the country. The war would not end well for the Tigrayans now, he said. They could not survive independently without the food and supply lines of the Welkait, which was currently held by Fano and federal forces, and they would not surrender their land.

In the end it seems they may have. The peace deal signed in November was more than anything a capitulation by the TPLF. By mid-September, the UN had equated the famine in Tigray to a crime against humanity, and by the end of October, the ENDF and Eritrean forces had captured key Tigrayan towns and cities. In addition to total disarmament and federal control of their state, the TPLF agreed to cease all hostilities against the government permanently, while no solution was offered to the problem of contested territory.

Shortly after the peace agreement, I got back in touch with Fentaw Asnake. He told me that during the summer he had been sent to the front lines, in both Amhara and Tigray. He was now back in Lalibela. “Peace is the best thing,” he wrote, “but still we are waiting [on] Welkait and Alamata”—another contested area—“to see what will happen.” Menber Alem, the Fano trainer, expressed a similar desire for peace and the same uncertainty, saying that Fano’s actions would depend upon Abiy’s choices, especially regarding the disputed land. “We’ll see what will happen,” he wrote.

Meanwhile, severe ethnic clashes unrelated to the conflict in Tigray have broken out in other regions, in the states of Oromia and Somali, where hundreds have died since June. The accord will have no effect there.

The TPLF started the war, Berhanu had told me repeatedly: the international community had forgotten this, or acted as if the fact were uncertain. As for “the specific atrocities that happened in the war,” those, he said, “are, to a certain degree, a derivative of this starting conflict”—that is, they were the fault of those who lit the match. When I replied that the war’s cause was perhaps not so simple, he answered: “Only in the minds of the West. We all here, we know how it started.”