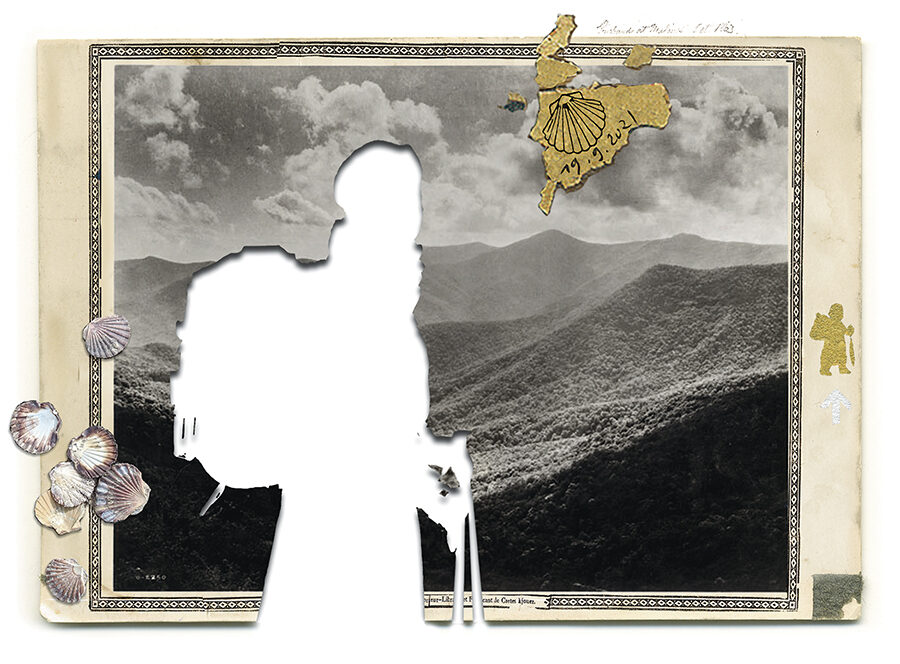

Collages by Jen Renninger. Source photograph of the Black Mountains by George Masa. Courtesy Buncombe County Special Collections. All other source photographs courtesy Ann Sieben

At the YMCA Blue Ridge Assembly, in the mountains outside of Asheville, North Carolina, pilgrims gathered. It was the beginning of April 2022, and in the way of that country, the days were warm and the nights were cool, and the morning fog that blanketed the valley below glowed blue. The camp conjured certain romantic and suspect associations, with its historic lodges wrapped in wide porches, their tall, white pillars smudged with the traces of a century of wear. An amalgam of cultural products signaling “the South” seemed to float in on the fog: corsets and crumbling antebellum mansions,…