The Incredible Disappearing Doomsday

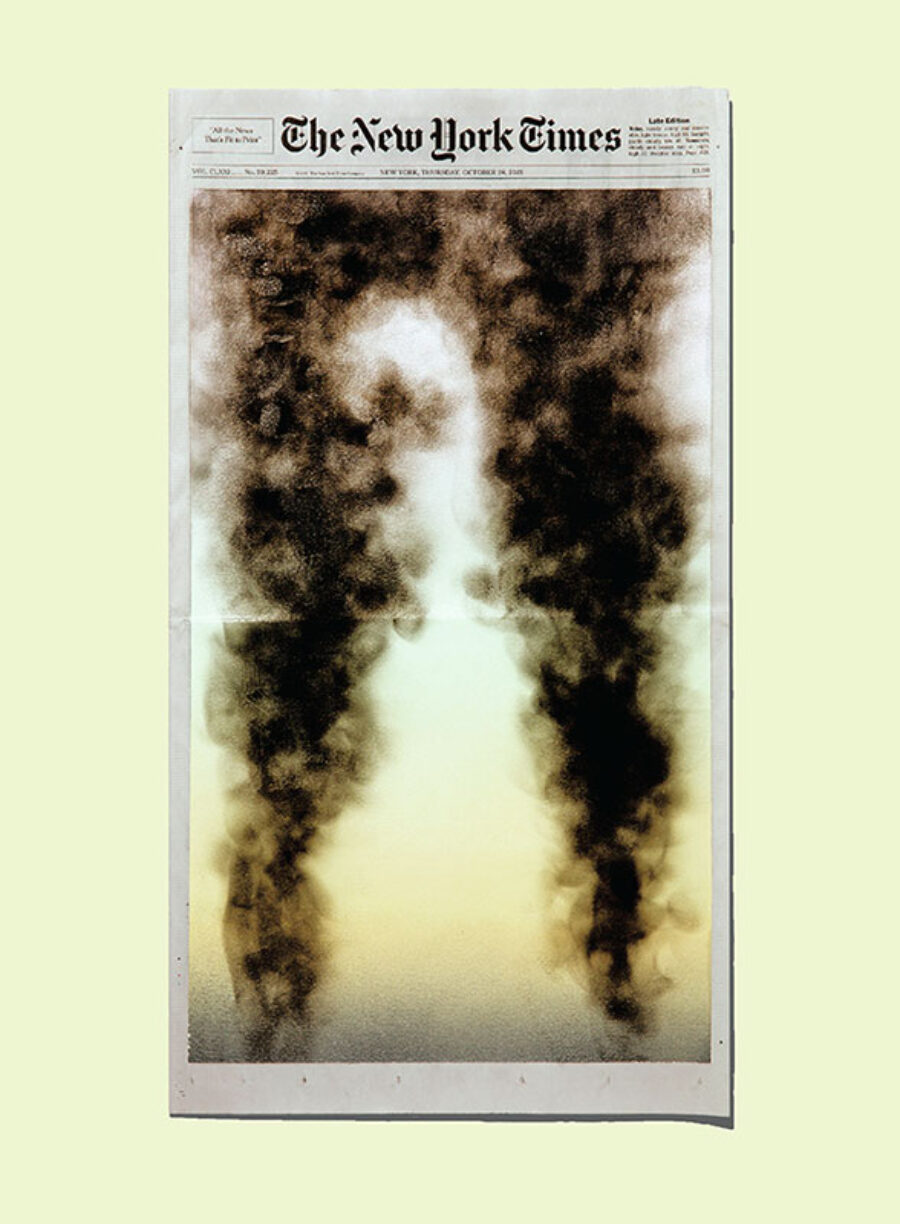

Bad News for the Planet, a painting by Sho Shibuya on the front page of the New York Times from October 28, 2021, shortly after the United Nations released its Emissions Gap Report. All artwork © The artist

The Incredible Disappearing Doomsday

The first signs that the mood was brightening among the corps of reporters called to cover one of the gravest threats humanity has ever faced appeared in the summer of 2021. “Climate change is not a pass/fail course,” Sarah Kaplan wrote in the Washington Post on August 9. “There is no chance that the world will avoid the effects of warming—we’re already experiencing them—but neither is there any point at which we are doomed.” Writing in the Guardian a few days later, Rebecca Solnit highlighted a paragraph from a recent report published by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) that said carbon-dioxide removal technology could theoretically “reverse . . . some aspects of climate change.” Though she admitted this was “a long shot” that would require “heroic effort, unprecedented cooperation, and visionary commitment,” Solnit nevertheless concluded, “It is possible to do. And we know how to do it.”

In the following months, a new mode of environmental reporting bloomed: the age of climate optimism was upon us. Elizabeth Weil captured the shift in a 2022 New York magazine story about how everyday people ought to contend with the crisis. Weil catalogued the usual depredations of her beat: fleeing a Marin County meditation retreat after wildfires fouled the air, crying about the gloomy future in the serenity of Houston’s Rothko Chapel. But her mood lifted during a rally marking the seventeenth anniversary of Hurricane Katrina. In rapturous terms, she described the scene under a highway overpass in New Orleans:

Flagboy Giz rapped about gentrification in his Wild Tchoupitoulas Mardi Gras Indian headdress. A woman sold shrimp and grits out of hotel pans. A man stood and watched for hours, a sleeping toddler on his shoulder. Nothing here looked like climate action. It looked like perseverance.

Each participant was contributing to what the activist Heather McTeer Toney called a “jazz sense of chaos” response to a warming world. “I’m playing the flute. Someone else over here is beating drums,” Toney told Weil. “We need those saxophonists that are going to do whatever the hell they feel like they want to do.”

In the media, writers and editors have also been uncasing their instruments. Last May the Washington Post executive editor Sally Buzbee announced an expansion of the paper’s Climate Solutions vertical, an initiative designed to highlight people and organizations “offering hope for the future” while at the same time “empowering readers to understand how they can make a difference.” To date, the section has run stories on the effort to ban plastic utensils and a Milwaukee-based reward program for informants of illegal dumping. More recently, the Post debuted Climate Coach, an advice column “about the environmental choices we face in our daily lives.” In the Los Angeles Times, the energy reporter Sammy Roth embraced the can-do turn in climate coverage. “Anyone who reads my stories knows I’m biased toward climate solutions, and my reporting flows from that,” Roth wrote. The happiest warrior of them all, the New York Times’s Nicholas Kristof, weighed in with a column titled “Cheer Up! The World Is Better Off Than You Think.” With global solar power capacity anticipated to nearly triple in five years, a breakthrough in the development of nuclear fusion, and advancements in battery storage, Kristof wrote that we were experiencing a “revolution of renewables”: “Progress is possible when we put our shoulder to it,” he concluded. “Onward!”

The sea change culminated last October, in the form of the New York Times Magazine’s annual climate issue, which featured comic-book-style depictions of “The New World” that climate change would create, illustrated by Anuj Shrestha and annotated by David Wallace-Wells. “Not very long ago,” Wallace-Wells wrote, some scientists believed that emissions “could cause four or five degrees Celsius of warming, giving rise to existential fears about apocalyptic futures.” Now a two-to-three-degree range was more likely, “thanks to a global political awakening, an astonishing decline in the price of clean energy, a rise in global policy ambition and revisions to some basic modeling assumptions.”

Shrestha visualized the future implicit in those projections, from the banal (palm trees growing in London, wind turbines off Coney Island) to the bleak (bleached coral reefs, desertification) to the already happening (a line of silhouetted migrants fleeing their homelands). The outlook was ambiguous, an idea Wallace-Wells expanded upon in a stand-alone essay titled “Beyond Catastrophe.” “We have cut expected warming almost in half in just five years,” he asserted. Now the culture was entering a new phase, one that traded alarmism and denialism for sober consideration of the adjustments required by a world whose transformation, however profound, would fall “mercifully short of true climate apocalypse.”

What made this contribution to the new mode so significant was its source: not so long ago, the same David Wallace-Wells was exalted as the most influential oracle of climate apocalypse. Just five years before writing “Beyond Catastrophe,” he had published a much-discussed New York magazine cover story, “The Uninhabitable Earth,” which became the most read feature in the magazine’s history. From its startling lede (“It is, I promise, worse than you think”) to its section headings (“Heat Death,” “Unbreathable Air,” “Perpetual War,” “Economic Collapse”), the article constituted an index of the planet’s future immiseration.

“Two degrees of warming used to be considered the threshold of catastrophe: tens of millions of climate refugees unleashed upon an unprepared world,” Wallace-Wells wrote in that piece. “Now two degrees is our goal.” For that reason, he shunned “the timid language of scientific probabilities,” and focused not on what the world would look like under two or three degrees of warming, but under numbers that seem outlandish now—at one point contemplating the human carnage of an eleven- or twelve-degree spike. The scientific underpinnings of his projections got wobblier the further he ranged from the direct effects on the weather. With five degrees of warming, he wrote, the planet “would have at least half again as many wars as we do today.” Turning seaward, he mused, “when the pH of human blood drops as much as the oceans’ pH has over the past generation, it induces seizures, comas, and sudden death.”

However jarring it is to compare this with the rosy picture in “Beyond Catastrophe,” Wallace-Wells is hardly the only journalist whose framing of the climate crisis has transformed in recent years. Where once the climate corps provided weary summations of daunting research, now they offer assurances that progress has been made and the future may be just fine. Given how quickly the tone has shifted, the average news consumer might assume that something fundamental has changed. Perhaps, thanks to all those new solar fields and international summits, a carbon-neutral future is already on the horizon.

Unfortunately, that is not the case. Global emissions have plateaued at a level that will likely produce 1.5 degrees of warming, meaning that billions of people will suffer. That isn’t good news in any sense of the phrase—it’s not good and it’s not even really news. Indeed, it is precisely the earlier work of the climate catastrophists that makes the present reality seem novel and agreeable. The facts have remained the same; only the story has changed.

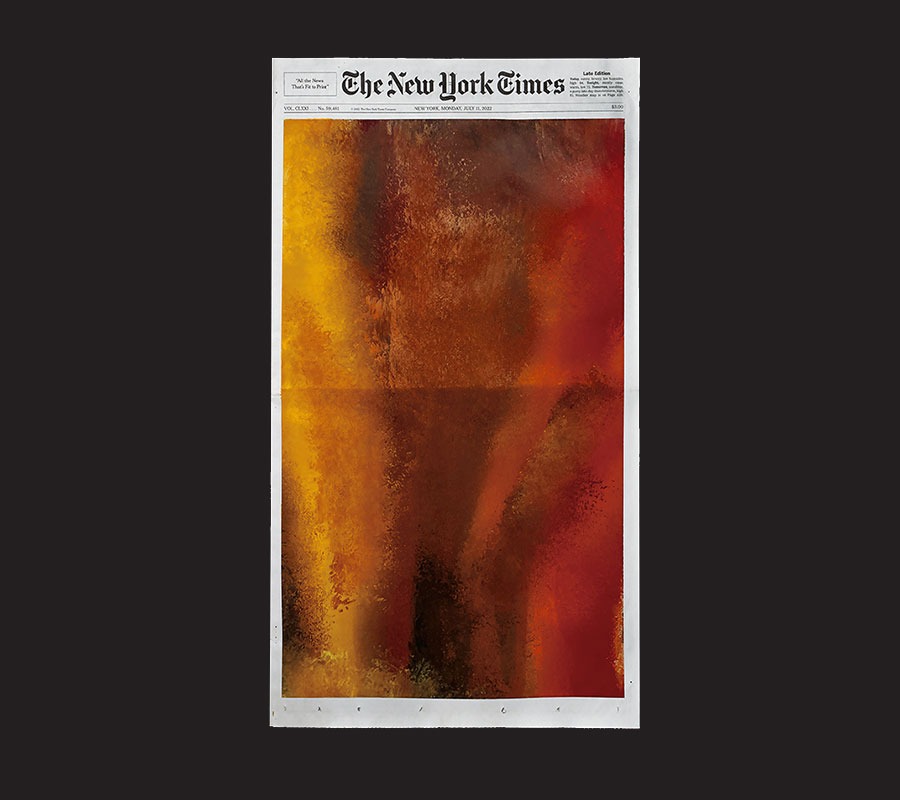

Yosemite, a painting by Sho Shibuya on the front page of the New York Times from July 11, 2022, as a wildfire swept through Yosemite National Park

The last time the tone of the conversation changed this drastically, it happened even more abruptly, over the course of a single night in 2016. “Pessimists will find abundant support for despair this morning,” the MIT researcher John Sterman announced the day after Donald Trump’s election. “It is now virtually certain the world will not meet any of its climate targets,” John Abraham wrote in the Guardian. In The Atlantic, Clare Foran called Trump’s victory a “triumph of climate denial.”

In the decade leading up to that election, the infuriating tendency of outlets to include quotes from fringe climate change skeptics had started to fade, allowing reporters to shed their defensive posture and explain what climate change was actually doing to the planet. During the Obama years, dispatches from Greenland and the Great Barrier Reef took the form of ever more explicit warnings. Once Trump took office, though, those fact-based stories began to alchemize into pseudoscientific visions of catastrophe.

In the early months of 2017, journalists catalogued a crack in an Antarctic ice shelf that had advanced seventeen miles in two months, the rapid thawing of Alaska’s permafrost, and the most destructive fire season in California’s history (which has since been surpassed—twice). The tipping point came that summer, when Trump pulled the United States out of the Paris accords and Hurricane Harvey sat over southeastern Texas for four days, dumping sixty inches of rain and killing dozens of people. To many Americans, it felt like climate change was suddenly happening everywhere, and the government was simply exacerbating the crisis.

With the present spinning out of control, writers began to cast a baleful eye toward the future. In 2017, Bill McKibben—one of the first journalists to alert the public to the dangers of a changing climate in the Eighties—wrote,

Our current business-as-usual trajectory takes us to a world that’s about 3.5C warmer. That is to say, even if we kept the promises we made at Paris . . . we’re going to build a planet so hot that we can’t have civilisations.

That prognosis came just months after Wallace-Wells had written that without “a significant adjustment” to how billions of humans lived, “parts of the Earth will likely become close to uninhabitable, and other parts horrifically inhospitable, as soon as the end of this century.”

The prophecies of Gehenna were both global—extreme heat becoming pervasive everywhere, from D.C. to Delhi—and hyperlocal, with Jon Mooallem leading a story in the Times Magazine with a map in which sea levels had risen by a fantastical two hundred feet, leaving San Francisco an archipelago, its famous hills now craggy islands overlooking the “Bay of Castro” and “Richmond Sound.” Even as Mooallem acknowledged that the “entire premise was unscientific; for now, it is unthinkable that seas will rise so high so quickly,” the way the map forced him to reconceive of his home catalyzed his sense that “the future we’ve been warned about is beginning to saturate the present.”

Against this backdrop, a sense of fatalism came into vogue, making contemplation of climate apocalypse a lucrative pursuit for writers of all stripes. “The Uninhabitable Earth” was adapted into a book that spent six weeks on the bestseller list, while “Losing Earth,” Nathaniel Rich’s Times Magazine cover story on the federal government’s inaction in the face of overwhelming scientific evidence was optioned by Apple TV. Allegory gained new currency in Hollywood, with Netflix’s Don’t Look Up skewering politicians’ unwillingness to contend with the obvious danger of an approaching asteroid and TNT’s Snowpiercer demonstrating how contemporary economic hierarchies would only grow more calcified during global disaster.

Literary writers similarly took up the mantle of Cassandra. Poems were published with such titles as “Letter to Someone Living Fifty Years from Now” and “Thirteen Ways of Looking at a Glacier (after Wallace Stevens).” In “Romance #1,” Eunsong Kim wrote, “i / keep waiting for capitalism to end / but it won’t end” before going on to list everything that would end, including “Hispid Hares / Starfish shaped like stars/ Inconvenience / Wrinkles / Sunken cheeks / Living corals.” Rich teenagers in Lydia Millet’s A Children’s Bible, published in 2020, discuss the number of generators their families installed in their survival compounds while the novel’s narrator frets about looping her kid brother in on the end of the world. “It was a Santa Claus situation,” Millet writes. “One day he’d find out the truth. And if it didn’t come from me, I’d end up looking like a politician.” Jenny Offill’s Weather, also from 2020, tracks the transformation of its librarian protagonist into “a crazy doomer” as she accompanies the host of a podcast called Hell and High Water to a series of increasingly frenzied speaking engagements. Eventually, the librarian realizes her sense of living on the brink of disaster has grown so acute that “the fact that there are six thousand miles of New York sewers and all of them lie well below sea level has become my go-to conversational gambit.”

Naturally, the storm clouds hanging over the arts couldn’t help but circulate back to the media. When I spoke to Elizabeth Weil this winter, she said that her decision to apply for a job covering climate change in California for ProPublica in 2020 was based partially on “living in the Bay Area, where these wildfires were happening and my kids weren’t going to school because of air quality,” and partially on reading Weather. “Offill was essentially asking, How do we write about this?” Weil told me. “What other notes can we be hitting to get people to pay more attention to this overwhelming issue that’s really hard to think about?”

Many of Weil’s peers share this impulse—not just to cover the facts of climate change, but to make readers really feel its impact. Not long after Wallace-Wells’s more sober take on the planet’s future was published in the Times Magazine, I asked him how it was possible that his oracular vision of the next century had changed so much in just five years. He said his reassessment of the situation actually dated to 2019, mere months after the book version of “The Uninhabitable Earth” came out, when he published a piece titled “We’re Getting a Clearer Picture of the Climate Future—and It’s Not as Bad as It Once Looked.” Still, Wallace-Wells insists that all his reporting on climate issues has been animated by a desire to share “what the science says is possible.” After reading the IPCC’s 2013 physical science report, as well as the research that followed, Wallace-Wells said he was spooked. “Scientists were quite focused on some really harrowing four, five, even six, seven, eight degree warming scenarios. Which I think really did point us to a different future than anything but what the most committed activists had permitted themselves to imagine.” (In other interviews, Wallace-Wells has also copped to allowing a general feeling of pessimism to color his work, connecting the tone of “The Uninhabitable Earth” to Trump’s election and his father’s death in 2016.)

Now, Wallace-Wells contends, the science has evolved. “It felt to me like really important news,” he said, “that, in a relatively short amount of time, the world’s energy modelers and climate scientists had pretty dramatically revised our expectations of warming this century.” Jake Silverstein, the editor of the New York Times Magazine, agrees with that assessment. “I don’t think of this piece as essentially a critique of his previous work for being alarmist,” he told me. “I see this piece as David doing one of the most important things we can do in this complicated field of climate journalism, which is to be willing to revisit past assumptions, because they are always changing.”

Did the science really change? Or was there simply a shift in how a handful of influential journalists interpreted it? The answer has to do with a set of future emissions scenarios called Representative Concentration Pathways, or RCPs, that are embedded in every IPCC report and numbered according to the predicted total energy in the earth’s climate system in 2100, relative to the preindustrial era. Since 1990, the IPCC has tracked four different RCPs, from RCP2.6, in which warming is significantly limited, to RCP8.5, where the emitters keep on emitting and the planet heats at a rapid clip. Though some independent studies have described RCP8.5 as “business as usual,” the 2013 IPCC report referred to it merely as “one scenario with very high greenhouse gas emissions.”

While RCP8.5 did indeed represent a worst-case projection—one in which, rather than transitioning to green energy, the world became ever more reliant on coal—at no point did the IPCC researchers assign relative probability to it, since it was intended only as a point of comparison. As Glen Peters and Zeke Hausfather wrote in a 2020 Nature paper, it was used to “benchmark climate models over an extended period of time, by keeping future scenarios consistent.” In fact, very little has changed in the climate modeling done by the IPCC since it began. Roger Pielke Jr. and Justin Ritchie, two researchers whose work has been central to debunking catastrophism, note that “the future envisioned by the IPCC has remained remarkably static,” with the range of possible temperature increases moving from between 2.9 and 6.2 degrees Celsius in 1990 to between 3 and 5.1 degrees Celsius in 2021.

All of this helps to explain why so many scientists were aghast at the extremity of the vision Wallace-Wells laid out in 2017. “Extraordinary claims require extraordinary evidence,” wrote the University of Pennsylvania environmental science professor Michael Mann. “The article fails to produce it.” The atmospheric scientist J. Marshall Shepherd tweeted, “Over the top alarmist articles about climate change are just as irresponsible as baseless skeptic claims.” The glaciologist Peter Neff noted the “significant literary license” that Wallace-Wells had taken, while Christopher Colose of the Goddard Institute for Space Studies was more pointed, calling the “nightmare scenarios” in the article “simply ridiculous.” “A ‘business-as-usual’ climate in 1-2 centuries still looks markedly different than the current one,” Colose continued, “but there’s no reason yet to think much of the world will become uninhabitable or look like a science fiction novel.”

“In the big picture,” Wallace-Wells told me, “RCP8.5 never should have been described as ‘business as usual.’ ” The closest he came to writing as much in last year’s Times Magazine piece was a passing reference to “revisions to some basic modeling assumptions.” Wallace-Wells seems to accept these revisions while also diminishing them, emphasizing the small number of people responsible for them and calling out Roger Pielke Jr. as a “frequent Republican witness at congressional climate hearings.” The numerous scientists who took direct issue with “The Uninhabitable Earth” go unmentioned.

Though Wallace-Wells does pass along Hausfather’s estimation that “about half of our perceived progress has come from revising these [warming] trajectories downward,” the justification given for his newfound bullishness is the growing influence of activists such as Greta Thunberg and the net-zero commitments that have been made by governments and corporations around the world, never mind the probability of those commitments ever being fulfilled—a gap between intention and action that Thunberg herself has highlighted repeatedly. In her speech at the 2021 Youth4Climate Summit, Thunberg cast the climate promises of the powerful as a whole lot of “blah blah blah.” Elizabeth Kolbert included the speech in an overview of the current state of the crisis published in The New Yorker last fall. “To say that amazing work is being done to combat climate change and to say that almost no progress has been made is not a contradiction,” Kolbert writes; “it’s a simple statement of fact.”

Kolbert’s article is organized around the alphabet, with the entry for the letter d reading, in its entirety: “Despair is unproductive. It is also a sin.” Under n, for Narratives, she cites evidence demonstrating that “a diet of bad news leads to paralysis, which yields yet more bad news.” Positive stories, on the other hand,

can also become self-fulfilling. People who believe in a brighter future are more likely to put in the effort required to achieve it. When they put in that effort, they make discoveries that hasten progress. Along the way, they build communities that make positive change possible.

Navigating this terrain is tricky for a journalist—how to tell a story that resists fatalism but doesn’t veer into advocacy? “The place I draw the line,” said the Los Angeles Times’s Sammy Roth, “is support for particular solutions. It’s not my job to say large scale solar installations are better than rooftop solar or vice versa.” At the same time, he said, “I want my journalism to have the result of helping to spur policies and technologies and a societal shift that reduces emissions.”

In the eyes of many, stories like “The Uninhabitable Earth” can have a similar effect. “David got a ton of pushback for that original piece but he also got a real conversation going that was necessary and helpful,” Weil told me. “People engaged with that story that hadn’t been engaging with the climate crisis, which is of great utility.” Of course, many specious stories get conversations going, particularly if you count “pushback” from experts as part of the conversation. What gets left out entirely are the costs of catastrophism—not just politically or socially but psychologically. Not to mention a further erosion of trust in journalism among precisely those people who need to be convinced that the problem we face is urgent and real.

For her part, Weil said that her recent feature was “very explicitly an experiment” in breaking down the binary between “doomism” and “blind hope.” That’s where the “jazz sense of chaos” comes in, as an inchoate model for responding to crisis. “You have to pull on these deep parts of humanity that are where the determination to survive comes from, outside the realm of the hard sciences where the climate discussion had happened for so long.”

Good News, a painting by Sho Shibuya on the front page of the New York Times from August 8, 2022, after the Senate passed a landmark climate bill

Given the totalizing nature of the climate story, it’s natural that there should be a wide variety of approaches to covering it, and it is admirable that writers are willing to take risks to write about the topic from differing perspectives, even if their efforts might appear misguided in retrospect. “If you look at our climate pieces over the years,” Silverstein told me, “you sometimes find pieces that are in gentle contradiction with each other—I think that itself is a reflection of us trying to have some journalistic humility in approaching something as vast and complex as climate change.” A range of views and analyses in one outlet is normal. More concerning is when an individual journalist sidesteps accountability for getting a story wrong.

It’s unlikely that today’s cautiously optimistic climate journalism will ripple through society quite as profoundly as the catastrophic mode did. Netflix surely isn’t cutting a $100 million check for a version of Don’t Look Up about an asteroid that might miss us. But the new climate journalism isn’t any more responsible. The world has yet to demonstrate the political will to save itself; stories that give readers the misleading impression that things will be just fine are overcorrecting for our prior fatalism, and risk replacing it with complacency. Writers like Wallace-Wells want us to believe that their own doom-peddling has chastened the world into a response that hasn’t actually occurred. The best course for many journalists may be to take a break from narratives and reconnect with the science.

It is, I promise, not quite as bad as you once imagined, but it is worse than you’ve lately been led to believe. The seas will rise, the summers will get hotter. There will be more red-sky days, more storms, more jungles turned into savannas and savannas turned into deserts. Global emissions may peak in a few years, but the subsequent decline will probably be too gradual to limit warming to even 2.5 degrees Celsius—the level that the United Nations projects the world’s net-zero pledges currently put it on track to reach. None of that constitutes an apocalypse, but it does suggest a world destabilized by hundreds of millions of people going hungry and being forced to flee their homes. The media’s job, in this moment, is not to raise alarms or offer assurances. It is to document the ongoing mutilation of our planet, and to push citizens, politicians, and corporations to stanch the carnage. Everything else is style that detracts from the substantive peril of the present.