Photographs by Lisa Elmaleh for Harper’s Magazine © The artist

I was splitting wood at sunset when the cat jumped up on the chopping block in front of me, arched her back, and took a long piss. My axe hung in the sky. The cat stared at me, tail up. I put my axe down and squatted before her. I hitched my gown to my waist. I sent my own stream into the brown leaves. The cat narrowed and widened her yellow eyes at me, which is what cats do because they can’t blink. Our eyes locked as we added our nitrogen to the landmass. She broke first, streaking back into the woods. I’ve never seen a cat piss or shit, not once they are out of their resentful kittenhood. Cats are private about such things. I have kept cats all my life. I say kept because my neighbor in these woods reminds me that no one can own a cat, not really. He says I should be more careful about language. He says that words have power. My hope every day is that he will leave me in peace.

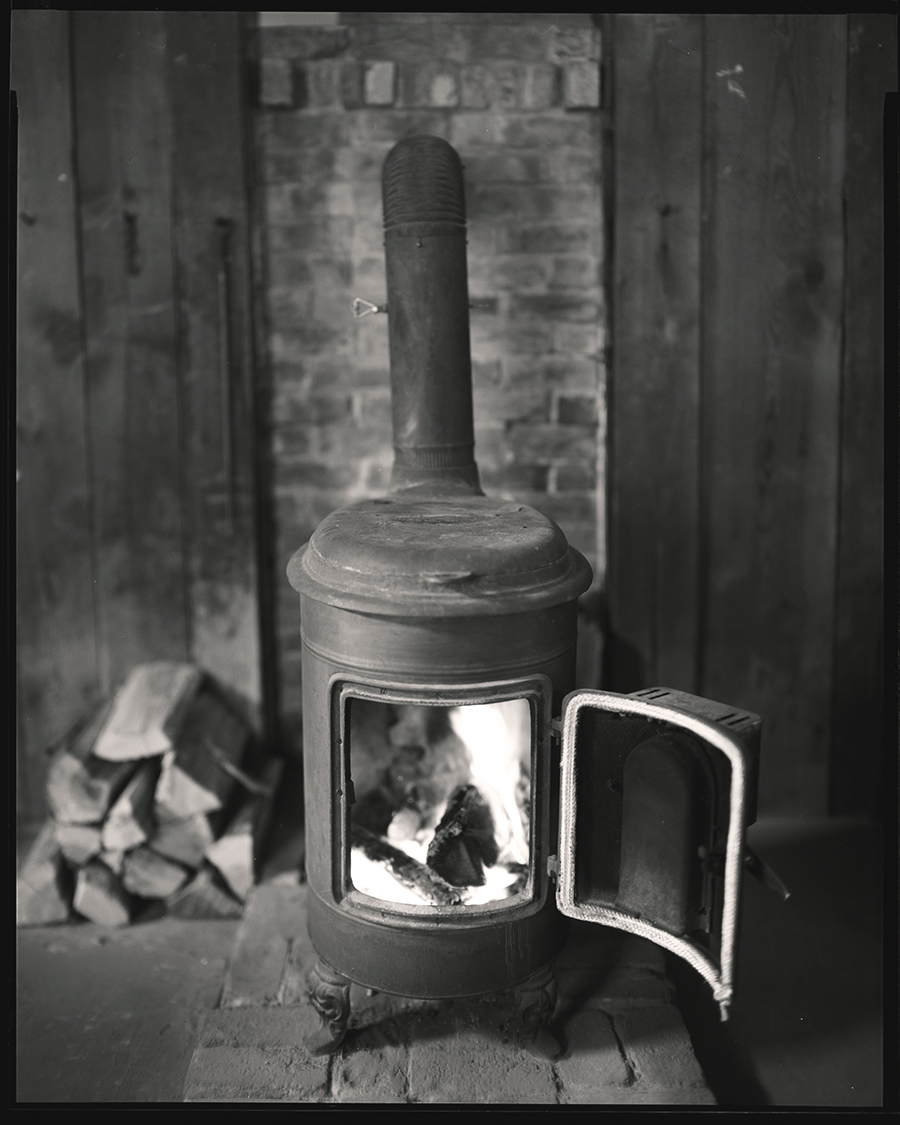

I swung my axe, trying to beat the dusk. I am particular about firewood. Sometimes firewood can feel like my whole life.

Tulip poplar wants to burn but it doesn’t give off much heat. I use it for kindling. It splits like a wooden xylophone. Listen for that muffled bell toll.

White elm is scarce now and red elm leaves behind clinkers. It will do. Across the grain, it’s a rich color without being ornate, which some people appreciate.

Hickory rots at the center so you can split it in a circle, like unmaking a barrel.

If it’s summertime and you’re cutting live trees, you’re screwed. You’ll be burning green wood all winter. All those long dark days your wood will spit at you, refuse to catch, need constant tending, smoke you out of your place without keeping you warm, and that’s not the worst of it. The worst of it is that green wood will build up creosote in your chimney, and your chimney will catch fire, and the fire will spread to your house, and your house will burn down and what will you do then.

My neighbor in these woods has already split, seasoned, and stacked all the wood he will burn this year. He did this last spring at the first thaw, as he has done every spring for the past twenty years. I don’t cut live trees anymore. When I need to warm myself, I look for standing dead. All winter, I stay one fire ahead of the cold. I’ve never been good at planning. I don’t know what’s going to happen and I don’t know why. I am, however, curious.

Oak will burn all night.

Persimmon is good hard wood but let it be. Wait for the first freeze and you’ll get fruit like deflated jewels.

Ash was on the chopping block in front of me, soaked in the urine of the cat. The emerald ash borer, radiant and misplaced, has killed all the ash, so what to do but fell it and watch its bark fall off like meat from the bone. Green ash burns better than any other green wood, though it’s useless to learn this. You should not burn green wood and you will not find an ash tree left alive.

Mid-swing, I saw it. Glistening in the piss. I bent to look. A drawing. A drawing in blue ink embedded in the tree rings. Nuanced borders, detailed topography, small as a badge. I had opened a tree and inside it found a map.

My neighbor used to have a book called Seeing Through Maps, written in a teacherly way that set my teeth on edge. “There are no rules for making maps,” the book said, clearly a trick to get you to let down your guard. Of course there are rules. You’ll be likely to break them. A map, by definition, is limiting. As with a journal, or any cavalier use of text, a map may help you remember things, but also invent a way of remembering them that makes you forget everything important. Instead of a journal, I made lists so banal that they unleashed my imagination in revolt against the tiresome record of my life. Instead of maps, I stayed home. I am certain my neighbor still has that book. He never gets rid of a damn thing that makes him feel good about himself.

There were two passages I could tolerate: “A map’s quality is the function of its purpose.” Also: “If you are making a map for your own purposes and do not care who else can read it—or do not want anyone else to be able to read it—the map need not even be intelligible to others.”

I put my face close enough to smell the ammonia. The blue lines could be a stamp, a tattoo, an island, a spit, an isthmus, a lake, a mountain of two lopsided circles. As a map it was unintelligible to me. Which, according to Seeing Through Maps, meant that I was not meant to understand it.

Is what I was thinking, leaning on my axe, when my neighbor appeared at the property line. I had marked those trees with orange blazes yet still I was not left alone. I could see him there, out of the corner of my eye, his patched coat that he’d made from three other coats, his tattered hood, his dirty scarf. “Permission to cross,” he said.

“Do it, then,” I said, and then I saw that he held his left hand awkwardly with his right as if it were an object separate from his body, and I saw that his left thumb was hanging from his left hand and that all the darkness he was flinging around, darker than dusk, was blood.

“I’m not sure I can drive myself to the emergency room,” he said, approaching. He had the pallor of someone in shock but still I could hear the recrimination in his voice. I waited to hear how his severed thumb was my fault. I was curious. My neighbor used to be my husband and neither of us has forgotten it.

“I was splitting kindling and the hatchet slipped,” my neighbor said. “You know, the hatchet that you gave me because you gave my first hatchet away.” He slumped against a sycamore, a tree that can give you a cough.

It’s true that I gave him a hatchet when we were first married, a beautiful curved instrument with a handle of striped walnut and a razor edge. It’s true that some years ago I reclaimed the hatchet so I could give it to our other neighbor, the younger one. When you give a gift, it’s important to give the best of what you have, not the least of what you have. My neighbor’s hatchet was the best thing I had. Of course I replaced it, but he remained angry. It’s easy to give the best of what you have when the best of what you have belongs to someone else, he said.

Maybe so. But if you had seen our young neighbor, a radiant person, you too would have given him a beautiful hatchet. You would have given him everything you had. Before he was our neighbor, he was our son. But it had been so long since I’d seen him, so long since I’d heard his voice, I was no longer sure whether I should call him our neighbor or call him something else, or no longer refer to him at all.

“That ash looks wet,” my neighbor said, squinting past me at the round as if it was his damn eyeballs that had been severed.

“Don’t talk,” I said. “Conserve your strength.” I tore a strip of cloth from my undergarment. My neighbor grunted as I tied his thumb back on the best I could. The blood soaked through the undergarment. I tore another strip. I tried not to breathe him in.

“Is it green?” he asked.

“I don’t burn green wood,” I said.

“Anymore,” he said. “You don’t burn green wood anymore. Let’s at least be accurate.”

“It’s cat piss,” I said. I let him lean on me as I guided him to the truck. I buckled his seat belt because he could not do it himself. I told him about the cat leaping onto the log, the eye contact, the stream of urine. I did not mention the map. I could see that through his pain he’d found something to focus on.

“The problem with you is that you have no respect for anything,” he said as I coaxed the engine. “When animals act like that, you should stop what you are doing. You should call it a day. You should go inside and shut the door tightly and stoke your fire.”

“But I didn’t have any firewood,” I said. The shocks were shot. The struts were rusted. At the bottom of the hill, the forest ended, and we waited at the railroad tracks as the coal train crept past, hopper car after hopper car, though I always looked for a boxcar, curious to see if someone might be inside.

“Chopping wood out of season,” he said, shaking his head. “Then the cat pees on the chopping block at dusk. Then you snub your nose at omens because you are desperate for warmth. Now you see what that leads to.” He held up his thumb, trailing my undergarment.

Finally, the striped gate lifted. The light switched from red to green. I steered around the potholes, the ruts and deep ditches, to the highway. If my neighbor had bled out while waiting for the train to pass he would have found some way to reprimand me for that too. He wasn’t one to let a little thing like death stand in his way. It must be comforting to my neighbor to know with such certainty how one thing leads to another. Causality is one of the major world religions, one of the last great articles of faith. To me, it is one of the great mysteries. And what is causality but blame?

The emergency room was full of all the people we tried to avoid, I mean any people at all, in various states of visible and invisible distress.

“You should go now,” my neighbor said. “You’ve got no wood and it’s going to be a cold one.”

“And how will you get home,” I said, “in the freezing middle of the night with blood loss? You can’t hitchhike with a thumb like that.”

The on-duty nurse, in her rolling chair, asked all the questions that my neighbor answered no to. No regular doctor. No phone number. No emergency contact. No insurance. No income, not this month at least. The nurse rolled her chair, rolled her mouth around.

“The doctor will still see you of course,” the nurse said. “But you will be expected to make a payment at the end of your visit.”

I lowered my neighbor into a chair like a blue plastic bucket so he could leave a grease stain, which, like I said, no longer had anything to do with me.

“We should go,” he said, closing his eyes and forgetting to hold his hand up.

“There’s no shame in resting for a minute,” I said. I took him by the elbow and guided his injured hand so that his uninjured hand could hold it. I certainly wasn’t going to. My undergarment grew crispy at the edges. I knew he wanted me to take him home and nurse him. I knew he wanted my entire damn undergarment, strip by strip.

In the adjacent bucket seat, a woman bluely changed her baby’s diaper, and the baby was not grateful at all, in fact the opposite.

“When my son was a baby,” I told her, “I told him I was going to change him. I meant his diaper. But my husband at the time said, Don’t tell him you’re going to change him because then he’ll believe we don’t accept him as he is. He’ll wonder if the universe fashioned him wrong.” The mother was about to respond, I swear she was, but her baby then kicked orange poop at her so I will never know what she was going to say.

“We hope you change,” I said to her baby, watching its mother wipe away the creamy shit while the baby screamed. “Because right now you are less than two feet long and you can’t focus your eyes. You are entirely unreasonable and you are too loud for mixed company.”

Words have power, my husband had said to me and to our similarly kicking soiled son. After that I stopped taking him seriously or I started taking him too seriously. Either one is the death of a marriage.

“There’s no way I can pay for this,” my neighbor said, grimacing.

“We could call him,” I said.

“Who,” he said, but I knew he knew.

Before he left the woods, our young neighbor had told us both to get health insurance, an easy thing to tell people to do. He told us many things, most of which I can’t remember because I thought he’d be there to remind me. He wanted us to stop replying to Do Not Reply text messages from collection agencies with sentences in all caps such as, YOU WILL NEVER GET A RED CENT FROM ME. It had been our health care strategy while raising him but apparently it was no longer good enough. He had called me exactly one time after I found his lean-to empty. Just to tell you I’m safe, he said. And to tell you I want you and Dad to take care of yourselves. He told me he had a job. A paying one. Something more real than being a consultant but less real than being a carpenter. Something in the middle. I can’t remember. But I remember that he made more in a year than I had made in my whole life. I remember when he told me, how gentle it was. I could hear the whole forest around me, wondering what the hell money was, what the word salary meant, was it close to the word salad or maybe salal. I want to be happy, he said. I want you and Dad to be happy, too.

Stupid forest, I said. Doesn’t understand what’s really important.

That’s my idea of a joke. That’s irony, which is like ironwood but easier for an axe to go through. My son has not called again. My text messages do not begin with Do Not Reply, but he does not reply.

A nurse called my neighbor’s name. He tried to get to his feet but sat back down hard. I hauled him up and went with him into the back and the nurse put us behind a curtain, through which we could hear all the clamor and beeping, the frequencies and trouble and off-color jokes, the tapping and sighing and coughing that filled up that building, which is why we tried to avoid buildings, and each other. But here we were.

The nurse took my neighbor’s vitals and asked him why he had filleted his hand. My neighbor looked at me as if I should be the one to answer.

“You’re making me hungry with talk like that,” I told her, because unlike my neighbor I understand humor. I understand that people who work in emergency rooms might want to use cooking or food metaphors to approach the horror that is human flesh. Unlike my neighbor I know that sometimes words have so much power that you can’t talk about what you’re talking about. You have to talk about something else.

The nurse left us alone, and my neighbor told me to reach into his pocket.

“Certainly not,” I said.

“It’s on my bad side,” he said. “Help me out.” In his foul pocket were six tiny persimmons. He used his good hand to take three of them.

“The persimmon tree is on my side of the line,” I said.

“The fruit fell on my side of the line,” he said.

We ate the persimmons. They revived my neighbor and they inspired in me a dastardly euphoria, unreplicable. They were exquisite.

When the young doctor came in, he tried to shake my neighbor’s hand, then remembered, so he shook hands with me instead. “I’m Dr. Rahim,” he said. “You must be the one making cannibal jokes. We love that kind of thing around here.” Dr. Rahim and I shared a hearty laugh. He read my neighbor’s name off a screen he held in his hand.

“Any relation to Duncan?” he asked, sitting down on his own rolling stool and unwrapping my blood-crusted undergarment. Neither my neighbor nor I said anything. “Had to ask,” he said. “Same last name. Small town.” My neighbor closed his eyes, as if it wasn’t his damn last name spilled over onto Duncan and me.

“We are Duncan’s parents,” I said.

“How about that? I love Duncan,” Dr. Rahim said, inspecting my neighbor’s wound. “Jesus, I’ve seen bratwurst more alive than this.” He winked at me. “Let’s see what we can do.”

“I also love Duncan,” I said.

“We were buddies in high school,” Dr. Rahim said. “Duncan’s much better at staying in touch than I am. Some people are so good at keeping up old relationships. Those high school days, though. When I think about how much trouble we used to get in.” He laughed. My neighbor opened his eyes.

“What kind of trouble,” he asked.

Dr. Rahim stopped laughing. “It was a long time ago,” he said.

“Still,” my neighbor said. “We are his parents. If he gets into trouble we need to know about it.”

“Just teenager stuff,” Dr. Rahim said. He looked at me, as if for assistance. But what did he think I should do? That man was only my neighbor. Only a distant pain. My relationship with my axe meant more to me than my relationship with him. Petting the cat was more interesting to me than my neighbor was. I had worked to edit our relationship back and back so that I barely knew him. Strictly speaking, he was none of my business.

Once, when my neighbor was still my husband, he caught me Velcroing Duncan’s tiny shoes, which Duncan could do himself by then but which I preferred to do for him when I could get away with it. My husband explained to me that Velcroing Duncan’s tiny shoes would lead to Duncan becoming prone to vices unimaginable and irreversible. Velcroing Duncan’s tiny shoes was in fact one of the primary ills facing our dying culture. My husband asked several questions, including what was wrong with me.

Where to begin. Mean mom, distant father, doesn’t know which colors flatter me, bad at dancing, bad baker, can only sing on key when no one is listening, only apologizes in order to get an apology in return, sad when it rains, can’t shake the childish sentiment that rain is God’s tears, doesn’t believe in God, inattentive pet escort. But by that time he had taken his hatchet and slammed out of the house. He was intuitive, imaginative, generous in his ability to link causes to events in the most expansive and unlikely ways. Yes, sometimes that could be difficult. You can do hard things, he told Duncan, refusing to Velcro his tiny shoes. No one could ever accuse my husband of shrinking before difficulties.

Dr. Rahim touched each one of my neighbor’s fingertips, in a way I had never done even when he was my husband. “You’ll need stitches, of course,” Dr. Rahim said. “Likely surgery too if you don’t want the nerve damage to be permanent.”

“I can’t afford that,” my neighbor said.

“Which,” Dr. Rahim said.

“Either,” my neighbor said.

“There’s a charity thing the hospital does for indigent or uninsured patients. You can grab the paperwork on the way out.”

“I don’t need charity,” my neighbor said.

Dr. Rahim frowned. “I understand the two of you may need to talk this over. Why don’t I give you a few minutes.” He once again gave me that significant look, which I had rejected my claim to years ago and did not in any way want back.

Dr. Rahim left, and my neighbor and I ate more persimmons. They were like if you never had to eat again. They were anti-patriotic, anti-abundance. They were surrounded by blame but blameless. They were mostly pit, but all around the pit they were perfect.

“We should call him,” I said.

“I did,” he said.

“You did?” I asked. “When?”

“Before I came to find you,” he said. “He was the first person I called.”

“What did he say?”

“I left a message,” he said.

“Do you think we were too hard on him?” I asked.

“No,” he said. “At least, I wasn’t.”

“I actually meant you,” I said. “I didn’t mean me. What about when he climbed the persimmon tree and shook them all down before they were ready and as punishment you made him eat all the unripe fruit until he vomited? What about snapping him into his snowsuit and forcing him to play outside alone in a blizzard?”

“You call that a blizzard,” my neighbor said.

“What about the nap tent? Knotting the zipper closed and letting him scream and cry sometimes for hours? Do you remember when he was too scared to hike with us in white fur coats along the ridge on a full moon and you made him do it anyway and he wet his pants? What about when you whipped him for insisting that everything was either a dog or a cat?”

Maple: cat. Elm: dog. Persimmon: dog. Dogwood: cat. Axe: dog. Hatchet: cat. Truck: dog. Creek: cat. Train: dog. Cat: cat. Squirrel: dog. Raccoon: dog. Spider: cat. It was a small thing, but it enraged my neighbor. Malingering, he called it. It was not honest, nor was it accurate. The one thing that stumped Duncan was a fox. To his father, he’d say that a fox was a dog. But to me he’d say a fox was a cat, because he knew I loved cats and he knew I loved foxes, although it’s been so long since I’ve seen one that I think they might not live in our woods anymore, and Duncan doesn’t live in our woods anymore either.

“The research shows it’s not actually people’s parents that make them who they are,” my neighbor said. “It’s other aspects of their environment.”

“But what were the other aspects of Duncan’s environment?” I asked. “You mean ash? Hickory? Oak?”

“His friends at school, for example,” my neighbor said. “Dr. Rahim. You heard him, they used to get in trouble together, and we’re only finding out about it now.”

Dr. Rahim came back. He was looking at his phone. “I have some good news,” he said.

“How much does it cost to amputate?” my neighbor asked.

“Duncan called,” Dr. Rahim said.

“No, he didn’t,” I said.

“He texted me,” Dr. Rahim said. “He said, I hope you’re taking good care of my folks. Let them know I’ll pay for it. Don’t let them try to stitch it themselves. Hahaha. But seriously. I told him to contact billing, of course. I don’t take care of all that. But I thought you’d want to know.”

“He texted you?” I said.

“Yes,” Dr. Rahim said.

“That’s gratitude,” my neighbor said. “Imagine that. The people who gave him life.”

“He’s paying your medical bill,” I said.

“Money means nothing to me,” my neighbor said.

“If you don’t mind, I’m going to sew that up for you,” Dr. Rahim said, taking his stool.

The nurse brought in a stainless steel tray. “From the cafeteria,” she said, looking at me, but I was no longer in the mood.

Dr. Rahim readied the suture. The needle went in and out of my neighbor like he was a burlap sack filled with potatoes or sand. I could not believe such a bloodless man had blood beneath his cracked skin. He watched the suture, chewing on his filthy beard.

My neighbor and I never exchanged rings. Instead, I gave him the hatchet and he gave me the axe I swing to this day. It has some magic in it. I consider it the only other woman around because it’s the only instrument that will do the work the way I want the work done. It’s my only companion, now that Duncan is gone. When I gave Duncan the hatchet, he almost didn’t take it.

It’s Dad’s prized possession, he said. How did you even get it from him?

I took it back, I said.

Does he know you have it? Duncan asked.

It belongs to you now, I said. But the hatchet did not make Duncan stay. He took it with him when he left.

My neighbor believes that blame, properly assigned, will bring our young neighbor home. What I wouldn’t give to hold such a belief, or any belief at all. If I could rekindle my faith in causality, then what I would like is a map showing me how I got here. I would like a map directing me to Duncan. But no such map exists, or if it does, it’s not a map I am meant to read. I stack wood for our young neighbor that is just the size for the woodstove in his lean-to. I keep his lean-to swept. I feed the cat, even though the cat is really Duncan’s, even though no one can really own a cat. I wait. I’m punky on the inside, fungus-filled. I’m eaten away, barely standing. I’m dead, and I’m burning, burning all the time.

“You’re going to have to stay off this hand for a bit,” the doctor said. “Hope you weren’t depending on it for anything.” He chuckled.

“Just kindling,” my neighbor said. “My wood’s all in.”

“That’s right,” Dr. Rahim said. “I remember Duncan used to talk about how his family heated with wood. I was always a little envious. To me it seemed quite adventurous. But didn’t he say your house burned down? Or someone’s house? Before he was born?”

“He was born,” I said.

“I built that house,” my neighbor said.

“Duncan was three when it happened,” I said.

“Passive voice,” my neighbor said.

“A hell of a thing to go through,” Dr. Rahim said. To my neighbor he said, “Until the stitches come out, your wife’s going to have to take care of your kindling.”

“I’ll split his kindling for him,” I said. “But I’m not his wife.”

My neighbor laughed.

“Forgive me,” Dr. Rahim said.

“There’s nothing to forgive,” I said.

“Then I hope you won’t mind me saying it’s inspiring to see you two still have such a strong relationship, even after your divorce,” Dr. Rahim said.

My neighbor and I stared at him. Divorce. What a powerful word.

Listen, we were like any other family. After the house burned, we took words apart and when we put them back together our relationship had changed. Our relationship to the word house. To the word together, to the word live, the word son, neighbor, family, to the word because, the word before and the word after. Eventually we lived on opposite sides of the forest. We drew Duncan a map so he could travel between us. As soon as he could, he constructed a lean-to. Please, he said, consider me as you would any other neighbor.

“Maybe this is too much information,” Dr. Rahim said. “But my wife and I are considering that right now. Conscious uncoupling.” It was too much information. We were simple people. The words we had already didn’t work and there was no indication that new ones with more syllables would work any better. “Please give Duncan my best,” Dr. Rahim said, depositing his latex gloves and his suturing materials into the biohazard container.

I drove my neighbor and his rotten hand home. He wolfed a pill prescribed by Dr. Rahim. For once he didn’t speak. What was there to say? It’s hard to do what other people want you to do. It’s hard to give someone your best. It’s hard to give someone the best of what you have. It’s hard to live with someone and also love them. I can do hard things. I can say things like, How was your day, which is effusive enough for some people. I can even say, When do you think this cold snap will end, or, Hey are we doing Christmas this year, or no just skip it, either way is fine with me. But words have power and mine were never powerful enough. Or they were too powerful. Either one is the death of a marriage.

Before the trees began, I steered the truck over the rise and dip of the railroad tracks, which made my neighbor curse. The striped gate was raised. The coal train was long gone. The animals hid in the dark of the forest, or they didn’t.

When I gave him the hatchet, Duncan told me, You ignored what Dad did to me. You went along with it. Never once, he said. Never once did you stand up for me.

But just because you don’t remember something doesn’t mean that it never happened.

I do remember. Duncan was three. He was in the nap tent. He was meant to be napping. My husband had split and stacked two cords of wood. He’d told me which cord was seasoned and which cord was green. Burn the seasoned wood, he said. Let the green wood season, and I agreed. But in those days I had no relationship with the words cord, ash, hickory, oak, cherry, maple, let alone the word green or the word seasoned. To me those words were decoration, pleasant and folksy, with no real power. I must have been burning green wood all that winter, and into the spring.

That day, after my husband went out, I packed the stove. While the creosote built and bubbled in the chimney, I made a list:

Cat food

Lysol

Dish soap

Laundry

Propane

Diapers

I tried to remember what it took for me to get here and I wondered if I would ever leave.

I burned with curiosity.

After a while it became difficult to concentrate. I tried to stay curious, but my curiosity was interrupted by a noise.

It was a noise that had been there all along.

It was Duncan.

Duncan screaming in the nap tent.

Duncan growing claws.

Duncan clawing to get out.

Duncan speaking and speaking, speaking powerfully but without words.

That time, I heard.

I looked once more at my list. I opened the stove. I tossed my banal list inside and watched it burst.

Then I undid the nap tent knot and I gathered my red and sweating boy, my panicked boy, my soiled boy. He doesn’t remember. He doesn’t remember that I stripped him of his diaper, and I cleaned him, and I changed him, and I wrapped him up and snugged him to my back. He doesn’t remember that we left. That we walked down the hill, out of the woods, that we came to the tracks and a train was passing. Dog, Duncan said. Dog. I watched a hopper car, a hopper car, a hopper car, then a boxcar. The train slowed so that we could walk alongside it. I climbed with Duncan into the boxcar and the boxcar picked up speed.

We were leaving, we were leaving, and with that wonder inside me, I watched our forest stay behind.

Cat, Duncan said, waving his hand, and there was a fox. The fox was trotting from the forest as if she had somewhere to go, but she stopped at the tracks. She waited for the train to pass, but the train lurched. Stopped. Started. Stopped again. The fox, waiting, spread her hind legs, put her ass down, and prepared to shit. Poo, Duncan cried, and the fox looked up and saw us. The fox saw us see her shitting. I saw her see us see her. She flattened her ears. The way she looked at us, angry, embarrassed, shocked, we knew it was wrong that we watched her deposit her black logs packed with feathers and bones, insects and fruit and seeds. High above her a column of black smoke plumed over the trees.

I may have no respect for anything, even the universe, but for twenty years I have wondered and wondered how one thing leads to another. I have wondered where my story begins. The fox is where I return. Everyone knows that if by some misfortune you see a dog shitting, you should hook your index fingers together or else there will be a consequence. Some say a wart will sprout. Some say it will be worse. But a fox is not a dog. A fox is not a cat. Should we have hooked our fingers? Duncan’s fingers were too small, and mine were wrapped around my baby boy.

The fox shit and then she dashed up the bank into the woods. The trees stood still. The boxcar stood still. Away down the tracks, I could still see the striped gate, beyond it our path home. We hadn’t made it very far. The train didn’t move. The temperature dropped. The sun went down. The wind picked up. Duncan said to me, Hungry. The boxcar said to me, Are you actually leaving? Do you know where you’re going? Do you know what you’ll do once you get there? Do you even have a map? I smelled the smoke. I burned with curiosity. But curiosity is something quite apart from the desire to know.

All I want is for you to be happy, I whispered to Duncan as I carried him back up the hill, toward the smoke and the man who would be my neighbor. My boy slept against me heavy as a river rock. I told him to be happy, but what did that mean? Only that amid the terror of such attachment, words don’t work. Now Duncan is out there somewhere, another happiness-pursuer, another person who may believe he deserves something, anything besides blame. For that and for nothing else I will apologize.

I parked the truck at the edge of the forest. I put the emergency brake on. I chocked the wheel. I helped my helpless neighbor out onto the forest floor. He used his good hand to switch on his headlamp and we wound through the trees we had marked with orange blazes to define a home.

My woman axe waited faithfully against the ash I had felled and bucked into rounds and wheelbarrowed to the chopping block so that the cat could piss on it, so that the urine could turn to crystals, which after long-term exposure can be mysteriously bad for your health. This is the type of causality you can watch. You can see it crystallizing. You may forget about it, but years later Dr. Rahim, or some other doctor who was a baby when your baby was a baby but who is now the one you trust your only body to, will look at you and break the bad news.

The cat slunk from the hut I built of particleboard and Tyvek near the burned-out foundation. Needily, she butted against my neighbor, who kicked her toward me. She put her rough tongue to my torn undergarment, curious.

My neighbor’s beam caught the map in the ash.

“Spalting,” he said.

“Spalting?”

“Those blue lines in the ash,” he said. “Spalting. It’s a process by which hard wood is eaten by fungi, requiring nitrogen, micronutrients, water, warmth, and air. It compromises the grain of the wood, but it’s much sought-after by woodworkers, not for structure but for beauty.”

“And for firewood,” I said.

“You wouldn’t catch me burning wood eaten up by fungus,” he said.

“To me, it looks like a map,” I said.

My neighbor bent closer, his thumb hovering upward. “You’re right,” he said. “It does look like a map.”

What was I to do? And don’t say be softened by the first words of affirmation he’d said to me in twenty years. Don’t say invite him in.

What looked like a map was not a map. What looked like a map was spalting, which is a word like sparrow, like salt, like salary. Just a word that could be grown over and enveloped, repurposed and subsumed like all the others.

“Do you need help with your fire?” I asked.

“I’ll manage,” he said.

“Are you happy?” I asked. “I mean, living the way we do?”

“I’m not the happiness type,” he said.

On that single affinity we had built a life.