Collages by Klawe Rzeczy. Source photographs: United States Air Force F-15E Strike Eagle on its way to Poland in support of NATO © Operation 2022/Alamy; Independence Monument in Kyiv © klug-photo/iStock; U.S. Marine Corps soldier © Michele Ursi/iStock; U.S. Marine Corps soldier and vehicle © Michele Ursi/iStock; Polish soldiers working with NATO allies © APFootage/Alamy; A member of a pro-Russian troop in an armored vehicle © Reuters/Alamy; An American soldier participates in a training exercise with NATO allies © APFootage/Alamy; Pro-Russian troops © Reuters/Alamy; Russian military leaders © Kremlin Pool/Alamy

From Murmansk in the Arctic to Varna on the Black Sea, the armed camps of NATO and the Russian Federation menace each other across a new Iron Curtain. Unlike the long twilight struggle that characterized the Cold War, the current confrontation is running decidedly hot. As former secretary of state Condoleezza Rice and former secretary of defense Robert Gates acknowledge approvingly, the United States is fighting a proxy war with Russia. Thanks to Washington’s efforts to arm and train the Ukrainian military and to integrate it into NATO systems, we are now witnessing the most intense and sustained military entanglement in the near-eighty-year history of global competition between the United States and Russia. Washington’s rocket launchers, missile systems, and drones are destroying Russia’s forces in the field; indirectly and otherwise, Washington and NATO are probably responsible for the preponderance of Russian casualties in Ukraine. The United States has reportedly provided real-time battlefield intelligence to Kyiv, enabling Ukraine to sink a Russian cruiser, fire on soldiers in their barracks, and kill as many as a dozen of Moscow’s generals. The United States may have already committed covert acts of war against Russia, but even if the report that blames the sabotage of the Nord Stream pipelines on a U.S. naval operation authorized by the Biden Administration is mistaken, Washington is edging close to direct conflict with Moscow. Assuredly, the nuclear forces of the United States and Russia, ever at the ready, are at a heightened state of vigilance. Save for the Cuban Missile Crisis, the risks of a swift and catastrophic escalation in the nuclear face-off between these superpowers is greater than at any point in history.

To most American policymakers, politicians, and pundits—liberals and conservatives, Democrats and Republicans—the reasons for this perilous situation are clear. Russia’s president, Vladimir Putin, an aging and bloodthirsty authoritarian, launched an unprovoked attack on a fragile democracy. To the extent that we can ascribe coherent motives for this action, they lie in Putin’s paranoid psychology, his misguided attempt to raise his domestic political standing, and his refusal to accept that Russia lost the Cold War. Putin is frequently described as mercurial, deluded, and irrational—someone who cannot be bargained with on the basis of national or political self-interest. Although the Russian leader speaks often of the security threat posed by potential NATO expansion, this is little more than a fig leaf for his naked and unaccountable will to power. To try to negotiate with Putin on Ukraine would therefore be an error on the order of attempts to “appease” Hitler at Munich, especially since, to quote President Biden, the invasion came after “every good-faith effort” by America and its allies to engage Putin in dialogue.

This conventional story is, in our view, both simplistic and self-serving. It fails to account for the well-documented—and perfectly comprehensible—objections that Russians have expressed toward NATO expansion over the past three decades, and obscures the central responsibility that the architects of U.S. foreign policy bear for the impasse. Both the global role that Washington has assigned itself generally, and America’s specific policies toward NATO and Russia, have led inexorably to war—as many foreign policy critics, ourselves among them, have long warned that they would.

As the Soviets quit Eastern and Central Europe at the end of the Cold War, they imagined that NATO might be dissolved alongside the Warsaw Pact. Soviet president Mikhail Gorbachev insisted that Russia would “never agree to assign [NATO] a leading role in building a new Europe.” Recognizing that Moscow would view the continued existence of America’s primary mechanism for exercising hegemony as a threat, France’s president Francois Mitterrand and Germany’s foreign minister Hans Dietrich Genscher aimed to build a new European security system that would transcend the U.S.- and Soviet-led alliances that had defined a divided continent.

Washington would have none of it, insisting, rather predictably, that NATO remain “the dominant security organization beyond the Cold War,” as the historian Mary Elise Sarotte has described American policy aims of the time. Indeed, a bipartisan foreign policy consensus within the United States soon embraced the idea that NATO, rather than going “out of business,” would instead go “out of area.” Although Washington had initially assured Moscow that NATO would advance “not one inch” east of a unified Germany, Sarotte explains, the slogan soon acquired “a new meaning”: “not one inch” of territory need be “off limits” to the alliance. In 1999, the Alliance added three former Warsaw Pact nations; in 2004, three more, in addition to three former Soviet republics and Slovenia. Since then, five more countries—the latest being Finland, which joined as this article was being prepared for publication—have been pulled beneath NATO’s military, political, and nuclear umbrella.

Initiated by the Clinton Administration while Boris Yeltsin was serving as the first democratically elected leader in Russia’s history, NATO expansion has been pursued by every subsequent U.S. administration, regardless of the tenor of Russian leadership at any given moment. Justifying this radical expansion of NATO, the former senator Richard Lugar, once a leading Republican foreign policy spokesman, explained in 1994 that “there can be no lasting security at the center without security at the periphery.” From the very beginning, then, the policy of NATO expansion was dangerously open-ended. Not only did the United States cavalierly enlarge its nuclear and security commitments while creating ever-expanding frontiers of insecurity, but it did so knowing that Russia—a great power with a nuclear arsenal of its own and an understandable resistance to being absorbed into a global order on America’s terms—lay at that “periphery.” Thus did the United States recklessly embark on a policy that would “restore the atmosphere of the cold war to East-West relations,” as the venerable American foreign policy expert, diplomat, and historian George F. Kennan had warned. Writing in 1997, Kennan predicted that this move would be “the most fateful error of American policy in the entire post-cold-war era.”

Russia repeatedly and unambiguously characterized NATO expansion as a perilous and provocative encirclement. Opposition to NATO expansion was “the one constant in what we have heard from all Russian interlocutors,” the U.S. ambassador to Moscow Thomas R. Pickering reported to Washington thirty years ago. Every leader in the Kremlin since Gorbachev and every Russian foreign policy official since the end of the Cold War has strenuously objected—publicly as well as in private to Western diplomats—to NATO expansion, first into the former Soviet satellite states, and then into former Soviet republics. The entire Russian political class—including liberal Westernizers and democratic reformers—has steadily echoed the same. After Putin insisted at the 2007 Munich Security Conference that NATO’s expansion plans were unrelated to “ensuring security in Europe,” but rather represented “a serious provocation,” Gorbachev reminded the West that “for us Russians, by the way, Putin wasn’t saying anything new.”

From the early Nineties, when Washington first raised the idea of NATO expansion, until 2008, when the U.S. delegation at the NATO summit in Bucharest advocated alliance membership for Ukraine and Georgia, U.S.-Russian exchanges were monotonous. While Russians protested Washington’s NATO expansion plans, American officials shrugged off those protests—or pointed to them as evidence to justify still-further expansion. Washington’s message to Moscow could not have been clearer or more disquieting: Normal diplomacy among great powers, distinguished by the recognition and accommodation of clashing interests—the approach that had defined the U.S.-Soviet rivalry during even the most intense stretches of the Cold War—was obsolete. Russia was expected to acquiesce to a new world order created and dominated by the United States.

The radical expansion of NATO’s writ reflected the overweening aims that the end of the Cold War enabled Washington to pursue. Historically, great powers tend to focus pragmatically on reducing conflict among themselves. By frankly recognizing the realities of power and acknowledging each other’s interests, they can usually relate to one another on a businesslike basis. This international give-and-take is bolstered by and helps engender a rough, contextual understanding of what’s reasonable and legitimate—not in an abstract or absolute sense but in a way that permits fierce business rivals to moderate and accede to demands and to reach deals. By embracing what came to be called its “unipolar moment,” Washington demonstrated—to Paris, Berlin, London, New Delhi, and Beijing, no less than to Moscow—that it would no longer be bound by the norms implicit in great power politics, norms that constrain the aims pursued as much as the means employed. Those who determine U.S. foreign policy hold that, as President George W. Bush declared in his second inaugural address, “the survival of liberty in our land increasingly depends on the success of liberty in other lands.” They maintain, as President Bill Clinton averred in 1993, that the security of the United States demands a “focus on relations within nations, on a nation’s form of governance, on its economic structure.”

Whatever one thinks of this doctrine, which prompted Secretary of State Madeleine Albright to dub America “the indispensable nation”—and which Gorbachev said defined America’s “dangerous winner’s mentality”—it lavishly expanded previously established conceptions of security and national interest. In its crusading universalism, it could be regarded by other states, with ample supporting evidence, as at best recklessly meddlesome and at worst messianically interventionist. Convinced that its national security depended on the domestic political and economic arrangements of ostensibly sovereign states—and therefore defining as a legitimate goal the alteration or eradication of those arrangements if they were not in accord with its professed ideals and values—the post–Cold War United States became a revolutionary force in world politics.

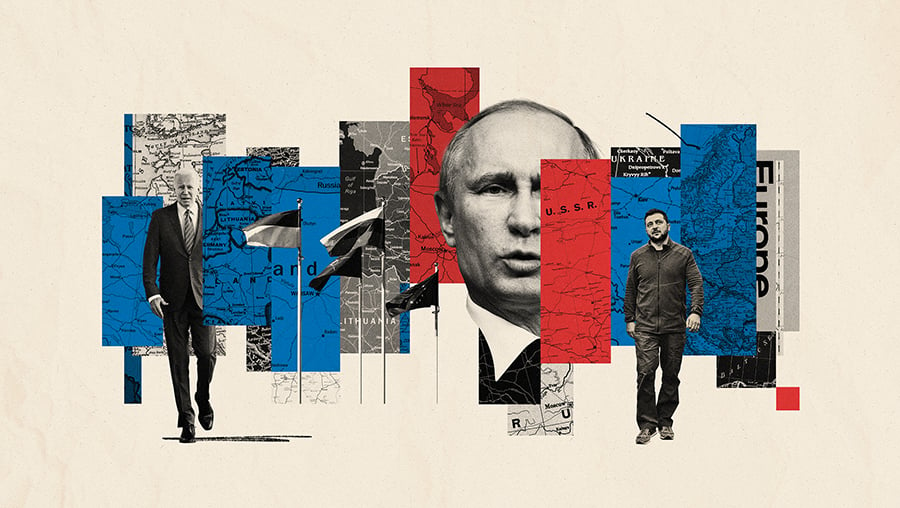

Source photographs: Flags of Ukraine, Lithuania, the European Union, and NATO © Panther Media GmbH/Alamy; U.S. president Joe Biden © Ukraine Presidents Office/Alamy; Ukrainian president Volodymyr Zelensky © Geopix/Alamy; Russian president Vladimir Putin © Peter Cavanagh/Alamy

One early sign of this fundamental change was Washington’s covert, overt, and (perhaps most important) overtly covert interference in Russia’s affairs during the early and mid-Nineties—a project of political, social, and economic engineering that included funneling some $1.8 billion to political movements, organizations, and individuals deemed ideologically compatible with U.S. interests and culminated in American meddling in Russia’s 1996 presidential election. Of course, great powers have always manipulated both their proxies and smaller neighboring states. But by so baldly intervening in Russia’s internal affairs, Washington signaled to Moscow that the sole superpower felt no obligation to follow the norms of great power politics and, perhaps more galling, no longer regarded Russia as a power with sensibilities that had to be considered.

Moscow’s alarm over the hegemonic role America had assigned itself was intensified by what could fairly be characterized as the bellicose utopianism demonstrated by Washington’s series of regime-change wars. In 1989, just as the U.S.-Soviet global rivalry was ending, the United States assumed its self-appointed role as “the sole remaining superpower” by launching its invasion of Panama. Moscow issued a statement criticizing the invasion as a violation of “the sovereignty and honor of other nations,” but neither Moscow nor any other great power took any explicit action to protest the United States’ exercising its sway in its own strategic backyard. Nonetheless, because no foreign power was using Panama as a foothold against the United States—and thus Manuel Noriega’s regime posed no conceivable threat to America’s security—the invasion neatly established the post–Cold War ground rules: American force would be used, and international law contravened, not only in pursuit of tangible national interests, but also in order to depose governments that Washington deemed unsavory. America’s regime-change war in Iraq—declared “illegal” by U.N. secretary general Kofi Annan—and its wider ambitions to engender a democratic makeover in the Middle East demonstrated the range and lethality of its globalizing impulse. More immediately disquieting to Moscow, against the backdrop of NATO’s steady eastward push, were the implications of the U.S.-led alliance’s regime-change wars in the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia in 1999 and, twelve years later, in Libya.

Although Washington presented the U.S.-led NATO bombing of Yugoslavia as an intervention to forestall human rights abuses in Kosovo, the reality was far murkier. American policymakers presented Belgrade with an ultimatum that imposed conditions no sovereign state could accept: relinquish sovereignty over the province of Kosovo and allow free reign to NATO forces throughout Yugoslavia. (As a senior State Department official reportedly said in an off-the-record briefing, “[We] deliberately set the bar higher than the Serbs could accept.”) Washington then intervened in a conflict between the brutal Kosovo Liberation Army (KLA)—a force that had previously been denounced by the U.S. State Department as a terrorist organization—and the military forces of the equally brutal regime of Slobodan Milošević. The KLA’s vicious campaign—including the kidnapping and execution of Yugoslav officials, police, and their families—provoked Yugoslavia’s equally vicious response, including both murderous reprisals and indiscriminate military actions against civilian populations suspected of aiding the insurgents. Through a stenographic process in which “ethnic-Albanian militants, humanitarian organizations, NATO and the news media fed off each other to give genocide rumors credibility,” to quote a retrospective investigation by the Wall Street Journal in 2001, this typical insurgency was transformed into Washington’s righteous casus belli. (A similar process would soon unfold in the run-up to the Gulf War.)

It was not lost on Russia that Washington was bombing Belgrade in the name of universal humanitarian principles while giving friends and allies such as Croatia and Turkey a free pass for savage counterinsurgencies that included the usual war crimes, human rights abuses, and forced removals of civilian populations. President Yeltsin and Russian officials strenuously, if impotently, protested the Washington-led war on a country with which Russia traditionally had close political and cultural ties. Indeed, NATO and Russian troops nearly clashed at the airport in Kosovo’s provincial capital. (The confrontation was only averted when a British general defied the order of his superior, NATO supreme commander U.S. general Wesley Clark, to deploy troops to block the arrival of Russian paratroopers, telling him: “I’m not going to start World War III for you.”) Ignoring Moscow, NATO waged its war against Yugoslavia without U.N. sanction and destroyed civilian targets, killing some five hundred non-combatants (actions that Washington considers violations of international norms when conducted by other powers). The operation not only toppled a sovereign government, but also forcibly altered a sovereign state’s borders (again, actions that Washington considers violations of international norms when conducted by other powers).

NATO similarly conducted its war in Libya in the face of valid Russian alarm. That war went beyond its defensive mandate—as Moscow protested—when NATO transformed its mission from the ostensible protection of civilians to the overthrow of Muammar Qaddafi’s regime. The escalation, justified by a now-familiar process involving false and misleading stories pedaled by armed rebels and other interested parties, produced years of violent disorder in Libya and made it a haven for jihadis. Both wars were fought against states that, however distasteful, posed no threat to any NATO member. Their upshot was the recognition in both Moscow and Washington of NATO’s new power, ambit, and purpose. The alliance had been transformed from a supposedly mutual defense pact designed to repel an attack on its members into the preeminent military instrument of American power in the post–Cold War world.

Russia’s growing concern over Washington’s hegemonic ambitions has been reinforced by the profound shift, since the Nineties, of the nuclear balance in Washington’s favor. The nuclear standoff between the United States and Russia is the dominant fact of their relationship—a fact not nearly conspicuous enough in the current conversations about the war in Ukraine. Long after Putin, and irrespective of whether Russia is converted to a market democracy, the preponderance of each country’s nuclear missiles will be aimed at the other; every day, the nuclear-armed submarines of one will be patrolling just off the coast of the other. If they’re lucky, both countries will be managing this situation forever.

Throughout the Cold War, Russia and the United States both knew that a nuclear war was unwinnable—an attack by one would surely produce a cataclysmic riposte by the other. Both sides carefully monitored this “delicate balance of terror,” as the American nuclear strategist Albert Wohlstetter put it in 1959, devoting enormous intellectual resources and sums of money to recalibrating in response to even the slightest perceived alterations. Rather than attempting to maintain that stable nuclear balance, however, Washington has been pursuing nuclear dominance for the past thirty years.

Beginning in the early Aughts, a number of defense analysts—most prominently Keir A. Lieber, a professor at Georgetown, and Daryl G. Press, a professor at Dartmouth and a former consultant to both the Pentagon and the RAND Corporation—expressed concern about a convergence of strategic developments that have been under way since the dawn of America’s “unipolar moment.” The first was the precipitous qualitative erosion of Russian nuclear capabilities. Throughout the Nineties and Aughts, that decline primarily affected Russia’s monitoring of American ICBM fields, its missile-warning networks, and its nuclear submarine forces—all crucial elements to maintaining a viable deterrent. Meanwhile, as Russia’s nuclear capabilities decayed, America’s grew increasingly lethal. Reflecting the seemingly exponential progress of its so-called military-technological revolution, America’s arsenal became immensely more precise and powerful, even as it declined in size.

These improvements didn’t fit with the aim of deterring an adversary’s nuclear attack—which requires only the nuclear capacity for a “countervalue” strike on enemy cities. They were, however, necessary for a disarming “counterforce” strike, capable of preempting a Russian retaliatory nuclear response. “What the planned force appears best suited to provide,” as a 2003 RAND report on the U.S. nuclear arsenal concluded, “is a preemptive counterforce capability against Russia and China. Otherwise, the numbers and the operating procedures simply do not add up.”

This new nuclear posture would obviously unsettle military planners in Moscow, who had undertaken similar studies. They no doubt perceived Washington’s 2002 withdrawal from the Anti-Ballistic Missile Treaty—about which Moscow repeatedly expressed its objections—in light of these changes in the nuclear balance, grasping that Washington’s withdrawal and its concomitant pursuit of various missile defense schemes would enhance America’s offensive nuclear capabilities. Although no missile defense system could shield the United States from a full-scale nuclear attack, a system could plausibly defend against the very few missiles an adversary might have left after an effective U.S. counterforce strike.

To Russian strategists, Washington’s pursuit of nuclear primacy was presumably still further evidence of America’s effort to force Russia to accede to the U.S.-led global order. Moreover, the means that Washington employed to realize that ambition would justifiably strike Moscow as deeply reckless. The initiatives the United States has pursued—advances in anti-submarine and anti-satellite warfare, in missile accuracy and potency, and in wide-area remote sensing—have rendered Russia’s nuclear forces all the more vulnerable. In such circumstances, Moscow would be sorely tempted to buy deterrence at the cost of dispersing its nuclear forces, decentralizing its command-and-control systems, and implementing “launch on warning” policies. All such countermeasures could cause crises to escalate uncontrollably and trigger the unauthorized or accidental use of nuclear weapons. Paradoxically, mutually assured destruction provided decades of peace and stability. To remove the mutuality by cultivating overwhelming counterforce (i.e., first-strike) capabilities is—in another paradox—to court volatility and an increased likelihood of a grossly destructive nuclear exchange.

Since the nadir of Russian power in the decade and a half following the Soviet collapse, Russia has bolstered both its nuclear deterrent and, to a degree, its counterforce capabilities. Despite this, America’s counterforce lead has actually grown. And yet, U.S. leaders often act affronted when Russia makes moves to update its own nuclear capabilities. “From the vantage point of Moscow . . . U.S. nuclear forces look truly fearsome and they are,” Lieber and Press observe. The United States, they continue, is “playing strategic hardball in the nuclear domain, and then acting like the Russians are paranoid for fearing U.S. actions.”

Source photographs: NATO tank © Callum Hamshere/Alamy; A tank participating in a training exercise © APFootage/Alamy; NATO soldiers © DPA Picture Alliance/Alamy; NATO flag © Peter Probst/Alamy; Jets © Dario Photography/Alamy; Soldiers after disembarking from a U.S. Air Force plane © ZUMA Press/Alamy; NATO fighter jet © Matthew Troke/iStock

The same solipsism defined America’s assessment of what it insisted was the Russian menace to NATO. Despite Moscow’s persistent warnings that it regarded NATO expansion as a threat, the swollen alliance intensified its provocations. Beginning in the Aughts, NATO conducted massive military exercises in Lithuania and Poland—where it had established a permanent army headquarters—and, on Russia’s border, in Latvia and Estonia. In 2015, it was reported that the Pentagon was “reviewing and updating its contingency plans for armed conflict with Russia” and, in likely contravention of a 1997 agreement between NATO and Moscow, the United States offered to station military equipment in the territories of its Eastern European NATO allies, a move that a Russian general called “the most aggressive step by the Pentagon and NATO since the Cold War.” The U.S. permanent representative to NATO explicitly identified “Russia and the malign activities of Russia” as NATO’s “major” target. The United States justified these moves as necessary responses to Russian hostilities in Ukraine and to the need, as the New York Times editorial board declared in a revival of Cold War rhetoric in 2018, to “contain” the “Russian threat.” And what made the Russians a threat? According to a 2018 report by the Pentagon, it was their intention to “shatter” NATO, the military pact arrayed against them.

While Russians of every political stripe have judged Washington’s enfolding of Russia’s former Warsaw Pact allies and its former Baltic Soviet republics into NATO as a threat, they have viewed the prospect of the alliance’s expansion into Ukraine as basically apocalyptic. Indeed, because from the beginning Washington defined NATO expansion as an open-ended and limitless process, Russia’s general apprehension about NATO’s push eastward was inextricably bound up with its specific fear that Ukraine would ultimately be drawn into the alliance.

That view certainly reflected Russians’ intense and fraught cultural, religious, economic, historical, and linguistic ties with Ukraine. But strategic concerns were paramount. Crimea (the majority of whose people are linguistically and culturally Russian, and have consistently demonstrated their wish to rejoin Russia) has been the home of Russia’s Black Sea Fleet, based in Sevastopol, since 1783. Since then, the peninsula has been Russia’s window onto the Mediterranean and the Middle East, and the key to its southern defenses. Shortly after the Soviet Union’s breakup, Russia struck a deal with Ukraine to lease the base at Sevastopol. Up until its annexation of Crimea in 2014, Russia worried that, were Ukraine to join NATO, Moscow would not only have to surrender its largest naval base, but that base would perforce be incorporated into a hostile military pact, which happens to be the world’s most powerful military entity. The Black Sea would have become NATO’s lake.

Western experts have long acknowledged the unanimity and intensity of Russians’ fear of Ukraine joining NATO. In his 1995 study of Russian views on NATO expansion—which surveyed elite and popular opinion and incorporated off-the-record interviews with political, military, and diplomatic figures from across the political spectrum—Anatol Lieven, the Russia scholar and then Moscow correspondent for the Times of London, concluded that “moves toward NATO membership for Ukraine would trigger a really ferocious Russian response,” and that “NATO membership for Ukraine would be regarded by Russians as a catastrophe of epochal proportions.” Quoting a Russian naval officer, he noted that preventing NATO’s expansion into Ukraine and its consequent control of Crimea was “something for which Russians will fight.”

Given these views, Russia’s ground rules for Ukraine—the epitome of realpolitik—were plain. As Yeltsin’s 1999 diktat to Ukrainian president Leonid Kuchma spelled out, Kyiv was not to enter into cooperative arrangements with, let alone join, NATO. Nor could Kyiv orient its foreign and economic relations toward the West in ways that disfavored Moscow. Yeltsin didn’t require Kyiv to orient its foreign or defense policies toward Moscow either. Understanding that NATO expansion couldn’t be reversed, Moscow’s vision of a lasting European security arrangement might have entailed varying degrees of arms limitations in the countries on NATO’s eastern glacis and a permanently neutral, eastern- and western-oriented status for Ukraine (somewhat like Austria’s Cold War status), including an agreement ruling out NATO membership. Washington fully grasped the cause and intensity of Moscow’s panic over the prospect of the West’s absorbing Ukraine into its orbit, as well as the diplomatic and security accommodations Russia required. But rather than attempting to reach a modus vivendi with Russia, U.S. officials continued to push for NATO expansion and supported color revolutions in Yugoslavia, Georgia, Ukraine, and other former Soviet republics as part of an apparent strategy to pull these areas out of Moscow’s orbit and embed them instead in Euro-Atlantic structures. By the second George W. Bush administration, Ukraine had emerged as the main arena of this competition.

Two critical events precipitated Russia’s war in Ukraine. First, at NATO’s Bucharest summit in April 2008, the U.S. delegation, led by President Bush, urged the alliance to put Ukraine and Georgia on the immediate path to NATO membership. German chancellor Angela Merkel understood the implications of Washington’s proposal: “I was very sure . . . that Putin was not going to just let that happen,” she recalled in 2022. “From his perspective, that would be a declaration of war.” America’s ambassador to Moscow, William J. Burns, shared Merkel’s assessment. Burns had already warned Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice in a classified email:

Ukrainian entry into NATO is the brightest of all redlines for the Russian elite (not just Putin). In more than two and a half years of conversations with key Russian players, from knuckle-draggers in the dark recesses of the Kremlin to Putin’s sharpest liberal critics, I have yet to find anyone who views Ukraine in NATO as anything other than a direct challenge to Russian interests.

NATO would be seen as “throwing down the strategic gauntlet,” Burns concluded. “Today’s Russia will respond.”

Appalled by Washington’s proposal, Merkel and French president Nicolas Sarkozy were able to derail it. But the alliance’s “when, not if” compromise, which promised that Ukraine and Georgia “will become members of NATO,” was provocative enough. Attending negotiations toward the close of the summit regarding cooperation in transporting supplies to NATO’s forces in Afghanistan, Putin publicly warned that Russia would regard any effort to push NATO to its borders “as a direct threat.” Privately, he is reported to have advised Bush that “if Ukraine joins NATO, it will do so without Crimea and the eastern regions. It will simply fall apart.” Four months later, as Burns had forecast, Moscow—having concluded that NATO’s incorporation of Ukraine was inevitable—responded by launching a five-day war with Georgia. Moscow’s focus on securing the breakaway regions of Abkhazia and South Ossetia, as opposed to embarking on a broader war of conquests, was consistent with Putin’s previous statements about what would happen if NATO threatened to expand farther east.

The second precipitating event came when Ukraine began talks about forming an “association agreement” with the European Union in September 2008 and, in October, applied for a loan from the International Monetary Fund to stabilize its economy after the global financial collapse. The association agreement, which eventually called for the “gradual convergence on foreign and security matters with the aim of Ukraine’s ever deeper involvement in the European security area,” would have precluded Ukraine from joining Moscow’s planned Eurasian Economic Union—a high priority for the Kremlin—while drawing Ukraine closer to the West. Plainly, the E.U. was seizing an opportunity to incorporate Ukraine into the West’s orbit, an outcome that Moscow had long defined as intolerable.

Ukraine’s pro-Moscow, democratically elected—though corrupt—president Viktor Yanukovych initially favored both the agreement with the E.U. and the IMF loan. But after U.S. and E.U. leaders began to effectively link the two in 2013, Moscow offered Kyiv a more attractive assistance package worth some $15 billion (and without the onerous austerity measures that Western aid would have imposed), which Yanukovych accepted. This course reversal led to the Euromaidan protests and ultimately to Yanukovych’s decision to flee Kyiv. Although much about these events remains unclear, circumstantial evidence points to the United States semi-covertly promoting regime change by destabilizing Yanukovych. A recording of a conversation between senior U.S. foreign policy official Victoria Nuland and the U.S. ambassador to Ukraine suggests that they even attempted to manipulate the composition of the post-coup Ukrainian cabinet. (A former adviser to Vice President Dick Cheney and longtime anti-Russia hawk, Nuland is now under-secretary of state for political affairs and a key architect of Washington’s response to the war in Ukraine.) To Moscow, these episodes of political interference further demonstrated Washington’s intent to bring Ukraine into the Western camp.

In response to Yanukovych’s downfall, Russia—just as Putin had intimated at Bucharest—annexed Crimea and stepped up its support for Russian-speaking separatist rebels in the Donbas. Washington in turn accelerated its efforts to pull Kyiv into the Western orbit. In 2014, NATO started training roughly ten thousand Ukrainian troops annually, inaugurating Washington’s program of arming, training, and reforming Kyiv’s military as part of a broader effort to achieve—to quote the State Department’s 2021 U.S.-Ukraine Charter on Strategic Partnership—Ukraine’s “full integration into European and Euro-Atlantic institutions.” That aim, according to the charter, was linked to America’s “unwavering commitment” to the defense of Ukraine as well as to its eventual membership in NATO. The charter also asserted Kyiv’s claim to Crimea and its territorial waters.

By 2021, Ukraine’s and NATO’s militaries had stepped up their coordination in joint exercises such as “Rapid Trident 21,” which was led by the Ukrainian army with the participation of fifteen militaries and heralded by the Ukrainian general who co-directed it as intending to “improve the level of interoperability between units and headquarters of the Armed Forces of Ukraine, the United States, and NATO partners.” Given the weapons and training the Ukrainian military had absorbed, and given Washington’s and NATO’s newly explicit diplomatic, military, and ideological commitments to Kyiv, and—most important—given NATO’s sophisticated program to integrate Ukraine’s forces with its own, Ukraine could now justifiably be seen as a de facto member of the alliance. Thus Washington had demonstrated its willingness to cross what William J. Burns—now Biden’s CIA director—had fifteen years ago called “the brightest of all redlines.”

Beginning in early 2021, Russia responded by amassing forces on Ukraine’s border with the intention—plainly and repeatedly stated—of arresting Ukraine’s NATO integration. On December 17, 2021, Russia’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs conveyed to Washington a draft treaty that reflected Moscow’s long-standing security aims. A key provision of the draft stated: “The United States of America shall undertake to prevent further eastward expansion of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization and deny accession to the Alliance to the States of the former Unionof Soviet Socialist Republics.” Other provisions proposed to bar Washington from establishing military bases in Ukraine and from engaging in bilateral military cooperation with Kyiv. A second draft treaty delivered to NATO called on the alliance to withdraw the troops and equipment it had been moving into Eastern Europe since 1997.

Far from expressing any ambition to conquer, occupy, and annex Ukraine (an impossible goal for the 190,000 troops that Russia eventually deployed in its initial attack on the country), all of Moscow’s demarches and demands during the run-up to the invasion made clear that “the key to everything is the guarantee that NATO will not expand eastward,” as Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov put it in a press conference on January 14, 2022. “We are categorically opposed to Ukraine joining NATO,” Putin elaborated two days before invading Ukraine, “because this poses a threat to us, and we have arguments to support this. I have repeatedly spoken about it.”

Even if Moscow’s avowals are taken at face value, Russia’s actions could be condemned as those of an aggressive and illegitimate state. At best those actions demonstrate Russia’s conviction that it has a claim to oversight of its smaller sovereign neighbors, a claim that accords with what Washington and the foreign policy cognoscenti condemn as a repellant concept: that of “spheres of influence.”

To be sure, any power imposing a sphere of influence is necessarily behaving in an implicitly aggressive manner. For a power to define an area outside its borders and impose limits on the sovereignty of the states within that area is contrary to the Wilsonian ideals that the United States has professed since 1917. In one of his last speeches as vice president, in 2017, Biden condemned Russia for “working with every tool available to them to . . . return to a politics defined by spheres of influence” and for “seek[ing] a return to a world where the strong impose their will . . . while weaker neighbors fall in line.” Because of America’s commitment to a just and moral world order, Biden insisted, quoting his own words from the Munich Security Conference in 2009, “we will not recognize any nation having a sphere of influence. It will remain our view that sovereign states have the right to make their own decisions and choose their own alliances.”

That straight-faced stance fails to recognize the spheres of influence, historically unprecedented in their sweep, that the United States claims for itself. Since promulgating the Monroe Doctrine two centuries ago, the United States has explicitly arrogated to itself a sphere of influence extending from the Canadian Arctic to Tierra del Fuego. But its globe-girdling sphere of influence also takes in the expanse, east to west, from Estonia to Australia and right up to the Asian mainland. Missing from the current discussion of the war in Ukraine, then, is any appreciation for how the United States would respond—and has responded—to foreign powers’ incursions into its own sphere of influence.

What, after all, would be America’s reaction if Mexico were to invite China to station warships in Acapulco and bombers in Guadalajara? For the past several years a civilian military analyst who has worked on international security issues with the Pentagon has put this question to the rising leaders in the U.S. military and intelligence services to whom he regularly lectures. Their reactions, he told us, range from cutting economic ties and exerting “maximal foreign policy pressure on Mexico to get them to change course” to “we need to start there, and then use military force if necessary,” revealing just how reflexively these military and intelligence professionals would defend America’s own sphere of influence.

Typifying the egocentrism that governs the U.S. approach to the world in general and relations with Russia in particular, not one of these future military and intelligence leaders has thought to connect, even in this past year, what they believe would be Washington’s response to the hypothetical situation in Mexico with Moscow’s reaction to NATO’s expansion and policy toward Ukraine. When the analyst has drawn those connections, the military and intelligence officers have been taken aback, in many cases admitting, as the analyst reports, “ ‘Damn, I never thought out what we’re doing to Russia in that light.’ ”

But America’s determination to uphold its own sphere of influence is more than hypothetical, as the Cuban Missile Crisis demonstrated. Thanks to a misleading rendition of events that members of the Kennedy Administration fed to a credulous press and later reproduced in their memoirs, most Americans see that episode as an instance of America’s justified resolve when confronted by an unprovoked and unwarranted military threat. But Russia’s deployment of missiles in Cuba was hardly unprovoked. Washington had already deployed intermediate-range missiles in Britain, Italy, and, most provocatively, in a move that U.S. defense experts and congressional leaders had warned against, on Russia’s doorstep in Turkey. Moreover, during the crisis, it was American actions—not Russian or Cuban ones—that would be considered aggressive and illegal under international law.

The parallels between Ukraine and Cuba run deep. Just as Moscow has justified its war in Ukraine as a response to a foreign military threat emanating from a neighboring country, so Washington justified its bellicose and potentially calamitous reaction to Soviet missiles in Cuba. Just as Ukraine, even before the Russian invasion, was well within its rights under international law to welcome NATO’s military support, so Cuba, as a sovereign state, had every right to accept the Soviet Union’s offer of missiles. Cuba’s acceptance was itself a legitimate response to aggression: The United States had been pursuing an illegal campaign of regime change against Cuba that included an attempted invasion, terrorist attacks, sabotage, paramilitary assaults, and a series of assassination attempts.

The United States may see Russia’s fear of NATO as unfounded and paranoid, and therefore incomparable to Washington’s reaction to the installation of intermediate- and medium-range nuclear missiles—armaments that President John F. Kennedy publicly declared were “offensive weapons . . . constitut[ing] an explicit threat to the peace and security of all the Americas.” But as Kennedy acknowledged to his special security advisory committee on the first day of the crisis, “It doesn’t make any difference if you get blown up by an ICBM flying from the Soviet Union or one that was ninety miles away. Geography doesn’t mean that much.” National Security Advisor McGeorge Bundy and Secretary of Defense Robert S. McNamara likewise conceded that the missiles did nothing to alter the nuclear balance. America’s allies, Bundy elaborated, were appalled that the United States would threaten nuclear war over a strategically insignificant condition—the presence of intermediate- and medium-range missiles in a neighboring country—with which those allies (and, for that matter, the Soviets) had been living for years. Summarizing the views of the majority of the advisory committee, Special Counsel Theodore C. Sorensen noted:

It is generally agreed that these missiles, even when fully operational, do not significantly alter the balance of power—i.e., they do not significantly increase the potential megatonnage capable of being unleashed on American soil, even after a surprise American nuclear strike.

Nevertheless, the United States deemed the strategically insignificant missiles an unacceptable provocation that jeopardized its tough-guy standing with its allies and adversaries, not to mention the Kennedy Administration’s electoral fortunes. (As McNamara acknowledged to the advisory committee on the very first day of the crisis: “I’ll be quite frank. I don’t think there is a military problem here . . . This is a domestic, political problem.”) Washington therefore embarked on an extreme, perilous course to force their removal, issuing an ultimatum to a nuclear superpower—an astonishingly provocative move, which immediately created a crisis that could easily have led to apocalyptic violence. Additionally, in imposing a blockade on Cuba—a gambit that we now know brought the superpowers within a hair’s breadth of nuclear confrontation—the administration initiated an act of war that contravened international law. The State Department’s legal adviser later recalled, “Our legal problem was that their action wasn’t illegal.”

So much for President Biden’s avowal that the United States bases its policy on the conviction “that sovereign states have the right to make their own decisions and choose their own alliances.” In short, in a foreign policy episode celebrated for its righteousness and wisdom, the United States, within its self-defined sphere of influence, committed several acts of aggression and war against its neighbor, a sovereign state, and committed an act of war against its global rival in order to force both states to conform to its will. It did so because, justifiably or not, it deemed intolerable its neighbor’s internal arrangements and security relationship with a foreign great power. In the process, it brought the world closer to Armageddon than at any point in history.

At least until now. The point here is not to make arguments of moral equivalency. Rather, given that, historically, Washington has responded aggressively to situations similar to those in which it has placed Russia today, the motive for Russian aggression in Ukraine is likely not expansionist megalomania but exactly what Moscow declares it to be—defensive alarm over an expansive rival’s military influence in a bordering and strategically essential neighbor. To acknowledge this is merely the first step U.S. officials must take if they wish to back away from the precipice of nuclear annihilation and move instead toward a negotiated settlement grounded in foreign policy realism.

To what degree would Washington even be interested in a negotiated resolution to the war in Ukraine? After all, a good deal of evidence suggests that the administration’s real—if only semi-acknowledged—objective is to topple Russia’s government. The draconian sanctions that the United States imposed on Russia were designed to crash its economy. As the New York Times reported, these sanctions have

ignited questions in Washington and in European capitals over whether cascading events in Russia could lead to “regime change,” or rulership collapse, which President Biden and European leaders are careful to avoid mentioning.

By repeatedly labeling Putin a “war criminal” and a murderous dictator, President Biden (using the same febrile rhetoric that his predecessors deployed against Noriega, Milošević, Qaddafi, and Saddam Hussein) has circumscribed Washington’s diplomatic options, rendering regime change the war’s only acceptable outcome. Diplomacy requires an understanding of an adversary’s interests and motives and an ability to make judicious compromises. But by assuming a Manichaean view of world politics, as has become Washington’s reflexive posture, “compromise, the virtue of the old diplomacy, becomes the treason of the new,” as the foreign policy scholar Hans Morgenthau put it, “for the mutual accommodation of conflicting claims . . . amounts to surrender when the moral standards themselves are the stakes of the conflict.”

Washington, then, will not entertain an end to the conflict until Russia is handed a decisive defeat. Echoing previous comments by Biden, Secretary of Defense Lloyd Austin declared in April 2022 that the goal is to weaken Russia militarily. Secretary of State Antony Blinken has repeatedly dismissed the idea of negotiating, insisting that Moscow is not serious about peace. For its part, Kyiv has indicated that it will settle for nothing less than the return of all Ukrainian territory occupied by Russia, including Crimea. Ukraine’s foreign minister Dmytro Kuleba has endorsed the strategy of applying enough military pressure on Russia to induce its political collapse.

Of course, the same momentum pushing toward a war in pursuit of overweening ends catapults Washington into pursuing a war employing unlimited means, an impulse encapsulated in the formula, endlessly invoked by Washington policymakers and politicians: “Whatever it takes, for as long as it takes.” As the United States and its NATO allies pour ever more sophisticated weapons onto the battlefield, Moscow will likely be compelled (from military necessity, if not from popular domestic pressure) to interdict the lines of communication that convey these weapons shipments to Ukraine’s forces, which could lead to a direct clash with NATO forces. More importantly, as Russian casualties inevitably mount, animosity toward the West will intensify. A strategy guided by “whatever it takes, for as long as it takes” vastly increases the risk of accidents and escalation.

The proxy war embraced by Washington today would have been shunned by the Washington of the Cold War. And some of the very misapprehensions that have contributed to the start of this war make it far more dangerous than Washington acknowledges. America’s NATO expansion strategy and its pursuit of nuclear primacy both emerge from its self-appointed role as “the indispensable nation.” The menace Russia perceives in that role—and therefore what it sees as being at stake in this war—further multiply the danger. Meanwhile, nuclear deterrence—which demands careful, cool, and even cooperative monitoring and adjustment between potential adversaries—has been rendered wobbly both by U.S. strategy and by the hostility and suspicion created by this heated proxy war. Rarely have what Morgenthau praised as the virtues of the old diplomacy been more needed; rarely have they been more abjured.

Neither Moscow nor Kyiv appears capable of attaining its stated war aims in full. Notwithstanding its proclaimed annexation of the Luhansk, Donetsk, Zaporizhzhia, and Kherson administrative districts, Moscow is unlikely to establish complete control over them. Ukraine is similarly unlikely to recapture all of its pre-2014 territory lost to Moscow. Barring either side’s complete collapse, the war can end only with compromise.

Reaching such an accord would be extremely difficult. Russia would need to disgorge its post-invasion gains in the Donbas and contribute significantly to an international fund to reconstruct Ukraine. For its part, Ukraine would need to accept the loss of some territory in Luhansk and Donetsk and perhaps submit to an arrangement, possibly supervised by the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe, that would grant a degree of cultural and local political autonomy to additional Russian-speaking areas of the Donbas. More painfully, Kyiv would need to concede Russia’s sovereignty over Crimea while ceding territory for a land bridge between the peninsula and Russia. A peace settlement would need to permit Ukraine simultaneously to conduct close economic relations with the Eurasian Economic Union and with the European Union (to allow for this arrangement, Brussels would need to adjust its rules). Most important of all—given that the specter of Ukraine’s NATO membership was the precipitating cause of the war—Kyiv would need to forswear membership and accept permanent neutrality.

Washington’s endorsement of Ukraine president Volodymyr Zelensky’s goal of recovering the “entire territory” occupied by Russia since 2014, and Washington’s pledge, held now for more than fifteen years, that Ukraine will become a NATO member, are major impediments to ending the war. Make no mistake, such an accord would need to make allowances for Russia’s security interests in what it has long called its “near-abroad” (that is, its sphere of influence)—and, in so doing, would require the imposition of limits on Kyiv’s freedom of action in its foreign and defense policies (that is, on its sovereignty).

Such a compromise, guided by the ethos of the old diplomacy, would be anathema to Washington’s ambitions and professed values. Here, again, the lessons, real and otherwise, of the Cuban Missile Crisis apply. To enhance his reputation for toughness, Kennedy and his closest advisers spread the story that they forced Moscow to back down and unilaterally withdraw its missiles in the face of steely American resolve. In fact, Kennedy—shaken by the apocalyptic potentialities of the crisis that he had largely provoked—secretly acceded to Moscow’s offer to withdraw its missiles from Cuba in exchange for Washington’s withdrawing its missiles from Turkey and Italy. The Cuban Missile Crisis was therefore resolved not by steadfastness but by compromise.

But because that quid pro quo was successfully hidden from a generation of foreign policy makers and strategists, from the American public, and even from Lyndon B. Johnson, Kennedy’s own vice president, JFK and his team reinforced the dangerous notion that firmness in the face of what the United States construes as aggression, together with the graduated escalation of military threats and action in countering that aggression, define a successful national security strategy. These false lessons of the Cuban Missile Crisis were one of the main reasons that Johnson was impelled to confront supposed Communist aggression in Vietnam, regardless of the costs and risks. The same false lessons have informed a host of Washington’s interventions and regime-change wars ever since—and now help frame the dichotomy of “appeasement” and “resistance” that defines Washington’s response to the war in Ukraine—a response that, in its embrace of Wilsonian belligerence, eschews compromise and discrimination based on power, interest, and circumstance.

Even more repellent to Washington’s self-styling as the world’s sole superpower would be the conditions required to reach a comprehensive European settlement in the aftermath of the Ukraine war. That settlement, also guided by the old diplomacy, would need to resemble the vision, thwarted by Washington, that Genscher, Mitterrand, and Gorbachev sought to ratify at the end of the Cold War. It would need to resemble Gorbachev’s notion of a “common European home” and Charles de Gaulle’s vision of a European community “from the Atlantic to the Urals.” And it would have to recognize NATO for what it is (and for what de Gaulle labeled it): an instrument to further the primacy of a superpower across the Atlantic.

That pact has made permanent what Kennan called, in 1948, “the congealment of Europe” along the line created by the U.S.-Russian standoff. Since the end of the Cold War, NATO has succeeded in pushing the borders of its own Iron Curtain “smack up to those of Russia” (as Kennan put it in 1997). By arousing Russian anxiety, it has heightened tension, conflict, and Russia’s most bellicose tendencies, thereby exposing both Europe and the United States to nuclear war. Depending on one’s point of view, membership in NATO entails either the prospect of sacrificing New York for Berlin (as the Cold War shibboleth held) or the prospect of “annihilation without representation” (as de Gaulle is reported to have put it). A new European security structure must therefore replace NATO.

This new system might embrace the notion of a community of Europe, but in reality the powerful states would exercise outsize influence (as they do in the E.U. and the U.N.). Such a system would in fundamental aspects resemble a modern Concert of Europe, in which the dominant states of the E.U., on the one hand, and Russia, on the other, acknowledge each other’s security interests, including their respective spheres of influence. In practice, this would mean, for example, that the Baltic states and Poland would enjoy the same large, but ultimately circumscribed, degree of sovereignty as, say, Canada does. It would also mean that, while Paris and Berlin won’t find Moscow’s internal arrangements to their taste, they will resume economic and trade relations with Russia and build on myriad other areas of common interest.

As for the future position of states such as Ukraine and Georgia, Europe’s (and Washington’s) approach would need to be similar to the approach that the diplomat Helmut Sonnenfeldt, while serving as a counselor at the State Department in 1976, advocated be taken toward the Soviet Union’s relations with its satellites:

a policy of responding to the clearly visible aspirations in Eastern Europe for a more autonomous existence within the context of a strong Soviet geopolitical influence.

Such an approach would reduce tension by recognizing Russia’s strategic interest in its sphere of influence, thereby inducing Moscow to exercise its claim of oversight in that sphere with as light a touch as possible.

Of course, whatever strategy Europeans work out regarding Moscow would and should be a matter entirely for Europeans to determine. Unavoidably, the pursuit of a new European security system—and the embrace of the old diplomacy that it would embody—would mean a substantially diminished global role for Washington. In allowing a Concert of Europe to act truly independently, Washington would effectively renounce the pursuit of global hegemony and the belief that its foreign policy should be guided by the conviction that, to quote President Clinton, it has a “particular contribution to make in the march of human progress.” In other words, the United States would accept that it would be what President Clinton promised it would not become, “simply . . . another great power.” Every post–Cold War president has recoiled from this role. But a more restrained and even pedestrian self-image might allow the United States at long last to pursue a more tolerant relationship with a recalcitrant world. “A mature great power will make measured and limited use of its power,” wrote the journalist and foreign policy critic Walter Lippmann in April 1965, three months before the United States committed itself to a ground war in Vietnam.

It will eschew the theory of a global and universal duty, which not only commits it to unending wars of intervention, but intoxicates its thinking with the illusion that it is a crusader for righteousness.

The policies that Washington has pursued toward Moscow and Kyiv, often under the banner of righteousness and duty, have created conditions that make the risk of nuclear war between the United States and Russia greater than it has ever been. Far from making the world safer by setting it in order, we have made it all the more dangerous.