Submersion Journalism

Illustrations by Chloe Niclas

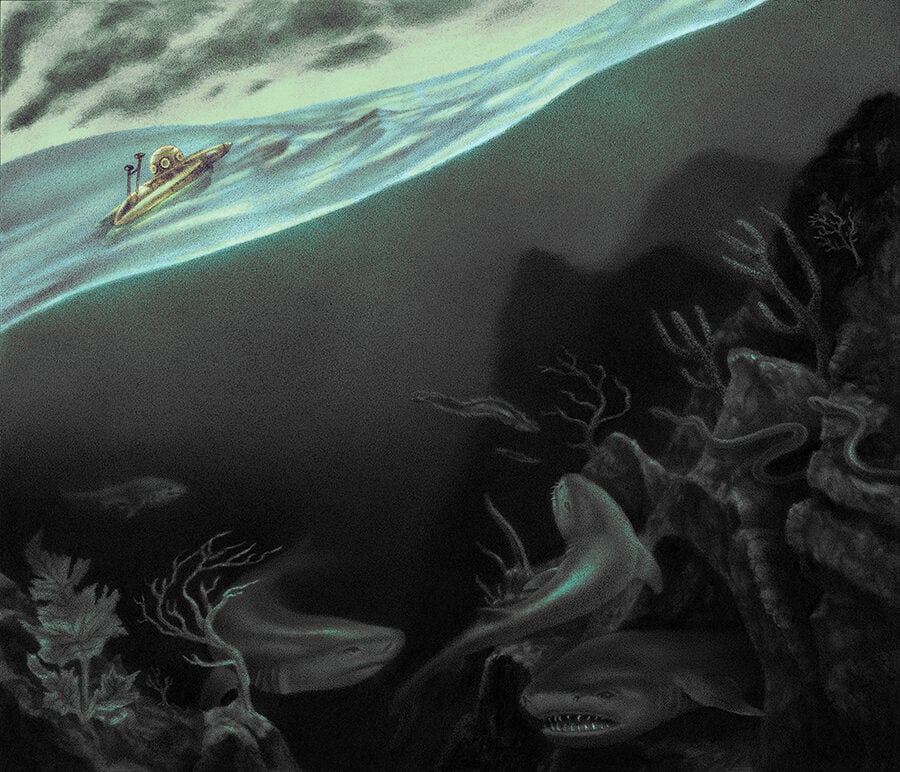

I can’t swim and I’m afraid of the ocean, and I was about to dive to two thousand feet in a home-built amateur submersible in the hope of spotting a giant sixgill shark feed from a slurry of fish and goat viscera that the amateur-submersible builder and captain, Karl Stanley, had dropped into the sea for my benefit the night before. It was early February on the coast of the Caribbean island of Roatán, in the Bay Islands archipelago of Honduras. Below us, in the water, was the Mesoamerican Barrier Reef. The sea was shamelessly turquoise, the clouds feathery; the palm fronds clacked like castanets. Karl’s neighbor, whose rumored profession it would not be wise to put into print, was blasting “Because I Got High” by Afroman on repeat.

“It was pretty rank,” Karl shouted, of the viscera, “fermenting in its own juices. The more the flies like it, the more the sharks like it. Even after I popped it in the chest freezer—a lot of flies.” He was forty-eight, and wearing baggy shorts. The breast pocket of his gray T-shirt was played out and sagging, as if it had stored all manner of nuts and bolts and the seashells he collects, and it flapped in the wind. He was six feet tall, but his brown hair, billowing above him, made him seem taller.

Karl strutted along his long wooden dock to his yellow submarine, scratched it affectionately at its neck, just behind the hatch. “The vehicle I’m operating,” he said of Idabel, the claustrophobic, nine-thousand-pound, three-person steel can I was about to board, “is the deepest-diving manned vehicle in the Western hemisphere south of the U.S.” Later, Karl would limit this claim to subs that dive from fixed home bases on shore, excluding vessels ferried on larger ships.

Idabel was roughly the shape of a tiny helicopter with a bulb on top—thirteen feet long, eight feet tall, six feet wide—and canary-meets-hot-dog-mustard yellow. It was suspended by an extra-strong polyethylene rope and grappling hook over a rectangular hole in the dock, below an awning where bright-red letters cut from PVC board entreated: go deeper.

The dock, beneath a canopy of white sunshades, was littered with wayward wires, bolts, straps, and tools. Karl yelled at his dogs—Doris and Mishka—who were racing by. If I’d arrived yesterday, he told me, I would have met his other dog, his favorite, a pitbull-mastiff mix named Kujo (like the Stephen King canine, but with a K, like Karl). But Kujo had been found dead that morning under a neighbor’s house, and Karl, sentimentally, had carried the body to his wheelbarrow and cut the dog’s head off with a hacksaw. The fireworms would now eat it to the bone. Then Karl would mount Kujo’s skull on the roadside façade of his home, next to the whitened horse pelvis and steer’s skull—the latter appointed with the ocular prostheses of two red Ping-Pong balls. “There was an open space there, so,” he shrugged. The house was a two-story clapboard, painted blue and sea-foam green, but the oceanside façade was a massive dead coral reef. Though there were four bedrooms in the house, Karl lived partially underground in a cavern he’d cut into the rock beneath the structure. He had no furniture save a bed on the stone floor, one foot above sea level.

“Those worms are crazy,” Karl went on. “Should be ready tomorrow.” He meant his dog’s skull. “Lots of things like that around here.” He said he’d spotted one of the island’s infamous snakes, a corn snake, the night before. I tried not to look around the yard. I didn’t want to see that wheelbarrow. I focused on Karl. The crust of last night’s sleep held to his lashes. He projected anxiety and calm, agitation and confidence. He was enduring me, and he was equipped to do so until the end of time. His voice was high-pitched and he spoke through clenched teeth. He sounded like the smartest child in the room, intriguing but also menacing—Big Bird on MDMA.

“A big one,” Karl continued. Five feet long. “We’ve crossed paths before,” he said. “I recognize him because, like, three inches of the end of his tail is missing. Something got him.” His voice trailed off. “Maybe a machete,” he muttered. He patted Idabel.

Karl had been diving in homemade subs for twenty-six years. Shanee Stopnitzky, a member of the amateur-submersible community whom I spoke with over video chat before my arrival, had told me wistfully, “Karl is a fucking weirdo. He’s amazing. He’s done more dives than just about almost anyone.” According to Karl, there are around one hundred home-built subs in the world and less than half of them are currently diving. Very few of those active subs dive past a hundred feet, and most go out only ten or twenty times a year. Karl, meanwhile, dives to two thousand feet about a hundred times a year. “By most metrics, he’s the most successful submarine person there is,” Stopnitzky said. “He’s, like, the person. He has a very serious love affair with the deep.” She closed her eyes and shook her head. “He’s very weird.”

Karl’s hair, blowing overhead, parted in the wind like grass under a tractor beam. I considered my lungs. I stared at Idabel and took inventory of my ailments. I was worried about my asthma, my high blood pressure, my anxiety attacks. I was worried that the retina in my left eye would unhitch with the pressure—about a month before, the vitreous in that eyeball had detached, which is to say that this was not at all impossible. I was worried about my small bladder: Idabel harbored no toilet. I live in a near-constant state of pee anxiety, and I’d had a lot of coffee. The dive was going to be three hours. I was worried that the hands into which I was about to place my life might not be especially interested in carrying it. Though I was a paying customer—Karl made his living taking strangers down to the deeps—I was also an obstruction to his solitude amid the fish.

I’ve had drowning nightmares since the age of four—nightmares that have persisted into adulthood with little variation: I’m standing waist-deep in the ocean. Onshore, my mother stretches out on an orange chaise longue beneath an orange beach umbrella, sipping chocolate milk from an orange thermos. In the sky, smoke snakes from an orange propeller plane. It’s trailing a banner behind it, advertising a sale on oranges. When the undertow sweeps my legs and sucks me farther out, I try shouting but water rushes into my mouth. I sink, surface, sink, surface. The world is muddied, the plane has crashed behind some luxury hotel, and my mother is standing, waving her arms over her head to signal to me, or to signal to someone to help me. The banner flutters in the air like an eel, shrouding the sun, dropping to beach grass. The luxury hotel bursts into flames. Chocolate is flying from my mother’s thermos. I go under and I don’t surface. My body feels as if it’s going to explode. An eel slithers by, slows, and stares at me unblinking as I wane. The world goes orange. I wake as I wane. I wake gasping.

My mother nearly drowned in the Atlantic as a child, swimming at Rockaway Beach. Her father—a used-car salesman who was not a strong swimmer—dove in and saved her life. A week later, he died in a car wreck. My mother never swam in the ocean again, and when I was a boy, seven or eight, she told me she believed that the sea had had some hand in her father’s death, that he’d died perhaps because he’d saved her. She told me this while comforting me after I’d woken up, screaming, from my ocean nightmare. I’d sweat through my Star Wars sheets. She sat on the edge of my bed, combing her fingers through my hair. She didn’t just fear the ocean; she distrusted it, felt it was conspiring to do us harm. She sat with me until dawn, until the woodpecker we always heard began feeding from the siding outside my bedroom window, like a metronome. “Don’t be afraid,” she said. But I didn’t believe she meant it. And whether through the story, or the hiccups of heritability, or her fingers through my hair, she sowed that fear and distrust into me.

I come from a long line of people who suffer from overwhelming OCD. I’ve channeled mine into becoming obsessed with obsessives—burrowing into the machinations and desires of one niche community or another in order to uncover or restore some bewildering intricacy to that which drives and defines us as a species, and to make some meaning of it, however illusory. But this time, I needed to map my own fears; Karl’s obsession could provide the relief. I wanted to unhook from my dream, and from the way I’d gone about living—fixated on, almost lionizing, the origins and qualities of my anxieties. A journey to the depths of the ocean had come to seem necessary. I wanted to differently greet the land, and my remaining time upon it, when I returned.

The night before the dive, soon after landing in Roatán, I went to dinner at Loretta’s Island Cooking, a tiny wooden bungalow nestled in the foliage of West End, where Karl lives. I texted Karl that I was there, about to eat the garlic conch, and he decided to join me, requesting that I order him the same; he’d be there in five minutes, he said. By the time he arrived, my conch was done and his was cold. He sat down and took his first forkful before saying hello.

Karl had lived on the island for nearly twenty-five years. He grew up in Ridgewood, New Jersey, and he said he’d known from a young age that he didn’t want to be like his father, wearing a suit and commuting to New York City. It seemed he’d spat in the face of what he now called “surface institutions” for most of his adolescence and young adult years. He’d begun nursing an obsession with submersibles at age nine, and at fourteen he made an unsupervised pilgrimage to Coney Island to see a Thirties-era bathysphere, a steel sphere that was once lowered on a cable to explore the deep waters off Bermuda.

Later that year, Karl was sent away, like Jacques Cousteau before him, to boarding school for reformation. He knew upon arrival at the isolated institution in the Maine woods, after his shoelaces were confiscated, that a traditional escape was out of the question, and he set about becoming an extreme nuisance. He woke in the night and screamed and screamed. His ace, he said, was a shower strike. He was quickly expelled. But his parents, convinced he needed psychiatric treatment, committed him to a county mental hospital, where some of the psychiatrists believed he had a condition he remembers as “defiance of authority syndrome.”

Karl had always wanted to build a submersible, and when he was released, after about six weeks, he channeled his anger at having been locked up into finally realizing his plans. At fifteen, he convinced his parents to buy him a welding machine, and he purchased his first piece of steel—a ten-foot-long pipe, two feet in diameter—with money earned doing odd jobs and working at the local ice cream shop. In the shade of an oak tree, and in a torrent of sparks, culling inspiration from books and magazines, museum dioramas, and old documentaries, he began shaping his first sub. He worked on it over the next eight years and eventually had it trucked down to St. Petersburg, Florida, where he attended college. It was there that he started going barefoot and developed a habit of climbing: high posts, a stadium floodlight, a radio tower over a thousand feet tall. It was also during this period that he hopped a freight train and rode it across the continental United States.

In its completed form, Karl’s submersible was a cylinder with two steel wings that glided through the sea without motors, guided by manipulating the volumes of water and air in its ballast tanks. Karl christened it C–BUG, an acronym for Controlled by Buoyancy Underwater Glider. After graduating from college, Karl stayed in Florida and spent nearly half of the next year underwater. At first, he tested C–BUG’s limits the way many backyard-sub builders test their vessels: by trial and error at depths where a leak or a gasket extruding or an outrigger imploding—all of which C–BUG endured—wouldn’t necessarily mean death. (To have a sub professionally tested for safety and design flaws was and is expensive—upwards of $15,000.) Then Karl took his trials deeper. He had C–BUG towed farther and farther into the Atlantic, where he was often harassed by the Coast Guard, who struggled to find a rationale for why he wasn’t allowed to take his vessel down. Being unmotorized, under twelve feet, and non-commercial, C-BUG was in the same regulatory category as a canoe and needed no license. But Karl was already conceiving of ways to monetize his dives. At a dive show in the summer of ’98, he met the owner of a place called the Inn of Last Resort, which resided at the end of a dirt road on a duodenum-shaped peninsula on the isle of Roatán, home to a brilliant fringing reef system rising up from the abyss of the Cayman Trench. In Honduras’s waters, Karl wouldn’t need to certify or insure his craft, a process that could cost upwards of $100,000 in the United States. And the Last Resort’s owner, who had purportedly trained Nicaraguan contra death squads in the Eighties, was looking to provide guests with a unique excursion experience.

So it was at the Last Resort, surrounded by jungle and monkeys that fed on hibiscus flowers, that Karl began his hustle, taking tourists down to depths unattainable by scuba endeavors. He found that his customers often treated the sub as a confessional, admitting their sins and regrets, seeking absolution from the sea or from him, the barefoot captain working his levers, spread-legged and aloof. These early dives were not without disaster. Three times, the porthole cracked and water sprayed in. On each occasion, Karl and his guests were able to surface, bursting through the waves to the air, seeing the sky, the trees, the rain, the sunset.

Karl knew that C–BUG’s operating depth was roughly six hundred feet. Taking a submarine too far down, even a few inches past its crush depth—1.5 to 2 times deeper than its operating depth—risks flattening the vessel like a stomped soda can. But Karl was obsessed with going farther and he pushed the sub’s limits. He admits that he once risked his life by taking it to 725 feet, which permanently deformed the vessel’s hull. He spent some of his nights on the sub, parking it on a coral ledge at five hundred feet, where there was a chance, albeit slim, that unexpected underwater forces could have sent C–BUG tumbling to its crush point.

In 2002, after spinning his wheels doing salvage work for the Cuban government—exhuming anchors and amphorae, and searching for sunken Spanish galleons rumored to be loaded with gold—Karl met an American businessman who connected him with an opportunity to rent an airport hangar in Oklahoma: there, he could build a new sub. Karl was hell-bent on voyaging to two thousand feet, what he calls “the land of perpetual darkness”—the habitat of creatures whose existence predates that of the dinosaurs—and he made the temporary move to Idabel, Oklahoma, population approximately seven thousand, amid pasturelands and stockyards, where, over the course of a year and a half, he built a craft designed to have an operating depth of three thousand feet.

At Loretta’s, Karl pushed a disc of conch around his plate with his fork, making conduits in the garlic sauce. I asked if there’d been consequences to his obsession. “I’ve shaped my entire life around being close to deep water close to shore,” he said. “It has definite shortcomings.” He told me he’d met a lot of people who, to his mind, hadn’t worked as hard, for as long, with as much passion, and who had a lot more to show for it.

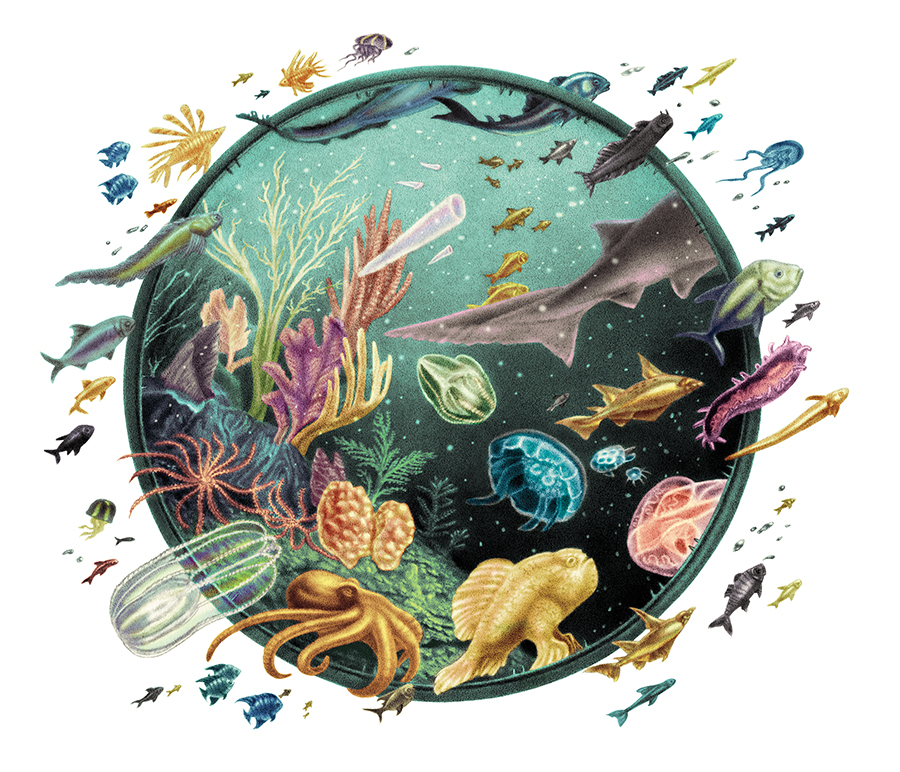

But it was the only way for him to live. “It’s a frontier,” he said. “No one can control you.” He told me that during our dive the next day we’d glimpse the bottom of the ancient reef upon which the entire island rests. We’d bob amid constellations of bioluminescent shrimp, crabs, half-shark-half-rays called chimeras. We’d see dumbo octopi that look as though they’re swimming with their ears, blue sea cucumbers, nudibranchs, moray eels, columns of mirror-like fish that hang in the water with their heads pointed down, a species of glass sponge that has survived four hundred million years, creatures that look like three-foot flowers, fish with legs that prefer walking to swimming. Limestone arches covered in sea lilies, he said. Deep-water coral that has lived two thousand years. The worthwhile stuff. It’s down there, he assured me.

Before the submarine, there was the diving bell, and before the diving bell there was the ephemeral but persistent human dream of sinking, a drive to float alongside the fishes, to see as they see. An early version of the diving bell—a rigid inverted cauldron lowered and raised from the surface by a cable—was mentioned in Aristotle’s Problems, a work believed to have been derived from a genuine Aristotlean text from the fourth century bc. Aristotle, who is often cited as the father of marine biology, spent at least five years of his life on the coast of Asia Minor, naming and classifying our sea creatures, distinguishing the “blooded” animals—the vertebrates—from the “bloodless”; the “soft-shelled,” such as lobsters, shrimp, and hermit crabs, from the “shell-skinned,” such as bivalves, gastropods, sea urchins, and sea stars.

Before the submarine, there was the diving bell, and before the diving bell there was the ephemeral but persistent human dream of sinking, a drive to float alongside the fishes, to see as they see. An early version of the diving bell—a rigid inverted cauldron lowered and raised from the surface by a cable—was mentioned in Aristotle’s Problems, a work believed to have been derived from a genuine Aristotlean text from the fourth century bc. Aristotle, who is often cited as the father of marine biology, spent at least five years of his life on the coast of Asia Minor, naming and classifying our sea creatures, distinguishing the “blooded” animals—the vertebrates—from the “bloodless”; the “soft-shelled,” such as lobsters, shrimp, and hermit crabs, from the “shell-skinned,” such as bivalves, gastropods, sea urchins, and sea stars.

As I considered his study of ocean life, I envisioned Aristotle lolling in a diving bell some unknown distance beneath the surface, the tether animated in the tides of the Aegean Sea. I imagined him obsessed with the goings-on of the watery world, sinking in a bell as often as he could, addicted to the deep sea’s ornaments. Of course, Aristotle would have been aware of the Hippocratic treatise on “madness,” titled On the Sacred Disease. The treatise described insanity as a condition in which the brain becomes “wet” and “corroded . . . melted”; “what is melted down becomes water, and surrounds the brain . . . and overflows it.” If Aristotle was obsessed with the sea, perhaps he believed that his time at depth might have begotten a sort of madness.

Aristotle tutored Alexander the Great for three years, beginning when the boy was thirteen, and in numerous medieval-era images of Alexander, he appears ensconced in a submersible, floating among fantastical creatures. In European, Arabic, and Persian adaptations of the Alexander Romance, a fiction laced with historical truths written sometime before 338 ad, the conqueror is likewise shown suspended in a capsule beneath the sea. In 332 bc, Alexander’s forces besieged and overtook the harbor city of Tyre; images from the Middle Ages depict the ruler watching the attack on the city’s underwater ramifications from a glass bell submerged in the sea. As I pored over these pictures, I imagined that Alexander had inherited his teacher’s obsession, using the diving bell as a space of placid retreat, a realm in which to meditate on all the blood he had shed and all the blood that he would shed still—that thanks to the bell he was able to conjure a sense of blissful calm as he was cutting someone’s throat, or, in the case of one legendary telling of the siege of Tyre, as he ordered the crucifixion of two thousand people on the beach before him.

Though Karl and I many times discussed his fixation on the deep as an “obsession,” he denied that the term applied in his case. “I’d say that if you want to be successful at certain tasks,” he told me, “you have to be ‘highly focused,’ or things won’t turn out well.”

The morning of the dive, I walked to Karl’s place from my motel, taking a wandering route through town. I’d slept poorly the night before and I passed along the streets as if through a fresh dream—by the bloody windows of the Rosita butcher shop, through the acrid smell of soap snaking from Cindy’s Laundry. The foliage was green and unruly and lurid. Seabirds argued in the open stairwells of the Arco Iris hotel. Men peddled brightly colored burner phones. Women peddled massages. I hung a right off the main drag and traveled north along the ocean, where the tawny glass of broken Salva Vida beer bottles glinted in the roadside dirt. A gecko called to me in a hoarse voice. Bull-shit, Bull-shit, it said.

I found Karl’s place just past a charter boat service called Ruthless Roatán, along the same pristine stretch where, after Great Britain’s Slavery Abolition Act of 1833, many former slavers from the Cayman Islands had relocated. In the centuries before, Spanish conquistadores, British colonial forces, and British, French, and Dutch pirates had each occupied Roatán for a time. The Spanish arrived first—Columbus landed on the Bay Islands during his fourth voyage, in the first decade of the 1500s. British colonists arrived on Roatán in 1638, inaugurating a two-hundred-year battle with the Spaniards.

The sun glared off the sea. As yet, I could only imagine Roatán’s underwater world. I recalled the legend of the sea monk—a monster that piqued the interest of European naturalists and whose fame spread like a virus during the sixteenth century. The monk was described as a ghoul with

a human head and face, resembling . . . the men with shorn heads, whom we call monks . . . but the appearance of its lower parts, bearing a coating of scales, barely indicated the torn and severed limbs and joints of the human body.

Historians remain uncertain as to the sea monk’s true identity: perhaps a giant squid or walrus. Perhaps a Jenny Haniver—a man-made creation of carcasses of skates or guitar fish, dessicated and manipulated to approximate some creature of myth, often a dragon or demon. Some historians have postulated that the monster could have been a Mediterranean monk seal. Though its presence was only reported near Europe, I wondered about the Caribbean monk seal, a now-extinct species that was abundant in these waters in the time of Columbus. Columbus had in fact claimed to have seen mermaids in the Caribbean, now believed to have been manatees.

I found Karl waiting on his patio, before the crooked pillars of dead coral holding up his home. My stomach had been unsettled, and I hadn’t eaten much. Karl offered me an orange. This did not bode well.

At the dock, Karl prepped Idabel, cleaning the portholes. He squatted, and his knees cracked. I didn’t ask him about the sea monk, though I was tempted. Instead I asked how he saw his obsession progressing. He sighed. He knew that his extraordinary nature obliged him to engage with plebes. He said he’d obtained a custom-made sonar map of the ocean features surrounding Roatán; with it, he planned to explore the area’s erosion channels, caves, boulder fields, knolls, and waterfalls of sand. He spoke wistfully of early Arctic expeditions. “I mean these guys had dibs on who was gonna get which part of the dog,” he said. “And they’re sharing a sleeping bag for body warmth and their buddy dies and they don’t get out of the sleeping bag until the corpse normalizes temperature, ’cause they want every last bit of warmth. To me that’s like . . . ” He stared off over my head into the foliage. “Yeah.”

Idabel swayed above the water, and Karl swayed on his feet like a tree. “I had a tenant suicide last May,” he said. He sometimes rented out rooms in the upper portion of his home. “I’m the one who cut him down.” Kujo had alerted Karl to the presence of the dead man’s ghost. “We buried him at sea,” he said. “I almost cut his head off to save his skull too, mount it on the house, but the authorities. And I heard he had like four kids, so.” Karl thought more people should get buried at sea. “A lot of people would be pleased with the idea of their body being eaten, given back to nature in the most direct way possible, and benefiting a large wild animal.” He was talking about the bluntnose sixgill sharks we were hoping to spot, which spend most of their day between three thousand and eight thousand feet below the surface. The fifteen- to twenty-foot-long Chondrichthyes could cause cosmetic damage to Idabel, but their beauty, Karl assured me, was worth the risk. Karl often haggles with local farmers to get livestock to use as lures—to, for example, “strap an eighty-pound pig to the side of the sub.” He’d captured one such instance with a GoPro, the video cast in red light, the dead little pig nodding forward and back as a shark bites into it, its gills waving open, deep as wounds. Karl also shoots and kills sick horses for bait. He’d seen sharks rip off whole legs and swim away with them dangling from their jaws like cigarettes, hooves knocking against gills. I pictured Idabel whirling undersea like one of those county fair swing rides, carcasses spinning out over the ocean floor: a dead horse, a pig, a deer—the last of these Karl had once tied to the sub by its antlers.

Karl talked as he uncoiled a length of wire. He said he’d wanted Idabel’s yellow color loud enough to be spotted by other ships in shallow water. No rescue vessel patrols the deep sea here, and Karl had decided to eschew communication systems for the sub. Attached to the steel encasing us would be no phone, no radio, nothing to cry “Mayday” into. He didn’t expect anyone in the area would be able to save him if something went awry and so considered these apparatuses just another layer of complication. “People say it’s asinine for anybody to be operating a manned sub without communications,” he said. “Everybody knows who they’re referring to. There’s nobody else doing that.”

The night before, after dinner, sitting at a picnic table on the beach, Karl had told me: “Dying early is failing. It’s fucking up.” I sipped a Salva Vida beer; Karl sipped a homemade medicinal tea. Failure was a “scalable problem,” he said; redundancies built into Idabel would keep us alive. There were two separate high-pressure air systems that could blast into two separate ballast compartments, and the propulsion system was fully doubled—separate battery banks and four motors when only two were needed. “I have motors fail once or twice a year,” Karl said. “My passengers never know.”

But he’d had close calls. C-BUG once got caught on a nylon line that Karl was threading through a shipwreck, intending to create a tether for a larger ship to use in salvaging the wreck later. The sub hiccupped as it ascended, and the line fluttered. There was enough air inside for Karl to survive for three days. It took an hour and a half to get free, but Karl admitted C-BUG could have hung there, snagged, for months or years, until a leak took it to the ocean floor, his corpse decomposing inside.

On the dock, Karl was rocking on his feet again, swaying as if to keep something insidious at bay. I mimicked him, and as I started, he stopped. With his toes, he dragged a bathroom scale from beneath a workbench and told me to hop on. We’d need to leave my shoes behind. With a whipping of his arm, and a groan that may have come from him or from Idabel, he yanked open the hatch. A seagull shat onto my left sock. Its shadow passed over Karl’s face. I was waiting for him to show some sign of affection or camaraderie. I was waiting, I realized, for him to hug me. The seagull moved on. Karl opened his mouth. This was going to be grave. “Climb in,” he said.

To enter the sub, I had to drop in, bracing my arms on either side of the hatch. The opening was just wide enough for me to fit, tight as those culverts my mother warned me about playing in as a kid on the outskirts of Chicago—perpetuating the suburban legend about some boy who crept inside, got tangled in trash, and died in the darkness, the rats rendering him to his skeleton, which washed out a year later. My mother would not have approved of this.

Wriggling through the chute, I lowered myself into the captain’s chamber, which was lit up red like old New Orleans, a series of dials and levers and cables stuck to the hull’s interior—some welded, some seemingly attached with Velcro and superglue. Karl’s chair was an old padded board. Squeezing through a second narrow chute, I entered the sphere at the bottom of the sub where I would travel and sat on a small bench before the pristine acrylic viewport—a concave hemisphere, four inches thick and thirty inches in diameter. Above me, in the upper chamber, a ring of smaller portholes haloed Karl, and he looked like a cartoon that had been thumped on the head, encircled by daffy birds. Another porthole was below me, at my socked feet, which rested on a canvas bag filled with lead shot—a weight that I would later pass up to Karl to keep Idabel balanced. The space seemed hardly larger than a clothes dryer, and I pressed my nose to the rounded viewport and breathed and waited and held my breath. It felt airless and humid. But I had brought a long-sleeve shirt in a plastic grocery bag; once we passed three hundred feet, the hull would become gradually colder. Karl pulled the heavy hatch door closed, and sealed it. My heart raced, and I sweat and bit my lip and I had to say something to him.

“It’s like we’re in a vacuum,” I said, and my voice echoed in a way that was too short, the silence of the space asserting itself, and shutting it up.

If the sub failed, we could suffocate. If we attempted escape, we could die from pulmonary hemorrhages. We could be knocked unconscious by the pressure, or succumb to arterial gas embolisms, or fall to swimming-induced pulmonary edema. We could certainly drown.

Through the porthole between my feet, the seagrass waved and skinny electric-blue fish emerged then disappeared into the blades. Karl was too busy potchke-ing with the dials to answer me. We descended from an electric hoist and the ocean lapped up over the viewport. Soon we were taxiing toward the subsea canyon where we would drop. Over the drone of a fan perched behind me, Karl spoke of the deep sea as a stable zone, supporting ancient creatures oddly suspended in time. It seemed to me a burial ground and a museum—interring vessels; the skeletons of long-extinct, still-unknown creatures; and the remains of people. On the dock, Karl had said he’d known of two divers who had committed suicide by unstrapping themselves from their gear. I imagined their bones untouched on the ocean floor.

“Here we go,” Karl said. He opened a valve, and air rushed from the ballast tanks. We went under, the depth-measuring dial to my left jumping to life.

I considered trusting in my distrust, and my fear of throwing up my own stomach—this happens to rockfish when they’re forced out of the deep—and demanding that Karl resurface before we dropped too far—we were only a few feet down, after all. Calling the whole thing off. I could have excused myself, and instead beheld the sea as only its surface, from the safe perch of that attractive café up the road, behind a platter of conch fritters.

And then, through the viewport, bioluminescent crumbs appeared, fluttered and flashed, and I couldn’t hold on to worry anymore, let alone the language I was used to attaching to it.

For the first thirty feet underwater, the surface light pinkened the reef, some dim wound-like throb hovering over the shadows of flying rays; schools of fish winking in and out as if stars. At four hundred feet, the languishing, condom-like pyrosomes bobbed at the whimsy of the water until stirred by a predator into bioluminescence, their openings dancing, a chorus of Munchian mouths beneath an unseen disco ball. Sponges and coral together resembled orange brains, a field of purple roses, the yellow branches of an endless quaking aspen. The bioluminescent crumbs were all sorts of creatures—crustaceans and dinoflagellates—and once they appeared, they never disappeared. They were there like the cosmos, whirling through the viewport.

At a thousand feet, the world was still dusky blue, a perpetual magic hour. A few hundred feet farther down, the ocean swallowed natural light, and went pitch-black. For us to see the things down there, they had to cross the beams of Idabel’s LED lights, where they appeared as silvery snakes, siphonophorous balls of golden yarn, an army of petal-like wings, pulsing. We floated with things that, after all of his diving, Karl still couldn’t name. These were so odd and unassimilable that I seemed to forget what they looked like even as I was looking at them.

At 1,500 feet, I shivered in my long sleeves. The condensation on the inner hull was frigid and began to pool at my feet, dampening the toes of my socks. We meandered amid a canyon of fallen coral boulders, where golden squat lobsters clung like spiders to sea fan webs. Two-hundred-year-old orange roughy sniffed the coral forests as if for the ghosts of their cousins whisked away to the diners of my childhood, chewed now by the ghosts of my long-dead grandparents at the early-bird special in the great beyond.

Polychaete worms writhed like chanterelle mushrooms belly-dancing. As we approached, colonies of glowing purple chandeliers broke apart and reformed. Red umbrellas became a red rain, then umbrellas again. A blue conger eel, six feet long, snaked from its lair in the coral, whipped like a wind sock. It gummed Idabel’s hull, decided we weren’t edible, and waving its tail, disappeared into its hole. Transparent creatures crossed the light and we saw straight through them, and the ocean warped strangely through the portals of their bodies. I was being pulled into these bodies, my brain wormholing, and I had to grind my teeth, rub my temples to stay with myself. To keep from floating away, from dedicating my body to the depth. I bit my tongue to the blood to prove my corporeality, remind myself that another kind of gravity existed and waited for us far above, where all that cruel, inspecting light would find us again.

At two thousand feet, the bioluminescent crumbs bunched together and, for a moment, I couldn’t see the ocean beyond them. Karl said, “Here we go.”

Idabel made a shushing sound, white noise. It was taking something in, or letting something go. I curled my toes in my wet socks. “What’s happening?” I said. I breathed against the cold condensation on the steel, expecting to see my breath, but didn’t. I wondered if I was really here. I squeezed my forearm and it felt real enough—or like a memory of what I was sure I used to feel, up on the surface.

“Shark,” Karl said.

“Where?”

“There.”

I couldn’t see through the curtain of bioluminescence, but soon it opened. I saw the eye first, glowing like a cat’s, then its face. The water around it went gauzy. The bioluminescence stilled. It was a sixgill, maybe twenty feet long, silvery-green, with a flattened head and rounded snout, and when it twisted, the flesh at its gills fanned open, then folded over on itself in cumulous bunches. It moved like the banner advertisement of my dream, falling from the Cessna to the fire. I reached for it, pushed my hand into the viewport’s cave. I probably said, Shit. I blinked, and I regretted blinking, because now it was only its tail, sweeping in a figure eight. And now, it was gone.

An orange octopus emerged from some hiding place. The ostracods, so-called strings of pearls—thousands of bioluminescent strands hanging in the water—twined like DNA. I wanted to say something to Karl, test my voice, but I couldn’t generate sound. I wasn’t sure why I was about to cry. Karl sighed, and it must have been a loud sigh if I heard it over Idabel’s drone.

Karl killed the motors and the lights, letting the air, fizzing into the ballast tanks, rocket us to the surface. Dramatically, but seemingly rehearsed, he counted down the last thousand feet of our ascent. “Four hundred,” he said.

“Three hundred.”

And in the darkest dark I’d ever been immersed in, the bioluminescence bounced against the viewport like sparks from an oxyacetylene torch, some frenzied constellation thrashing, undoing itself, some mosh-pit hyperspace.

“Two hundred.”

Idabel became hot and humid again. The light from the surface began to penetrate the water, and I could see the coral walls, where seagrass flashed as if with tea lights. My heart accelerated, and my body remembered who I was, and though we were out of certain-death-if-something-goes-awry territory, anxiety crept back in.

“One hundred.”

And I had nothing to say.

We burst through the surface, foam pluming over the viewport, and there, muddied through the rinse of seawater, were the orange lights of town, human stuff. It was pushing 9 pm. Soon, I would hear the mopeds and diesels and honking horns along the beachfront road. I felt a great, implacable sadness, but I also wanted to laugh—cackle, actually. We stayed silent as we rumbled toward the dock. I tried to think about what had happened, sew words into it. Yes, there had been awe and wonder, but now I felt a funereal sense of loss. The invisible comprises so much more of our world than I had understood; time had cracked. I knew I would never be able to experience it all again, the way I knew I would never again hear the voices of those who had died. Unstuck from, if not beyond, fear and anxiety, I was aware of myself as a crumb on the continuum. And because I cannot bioluminesce, I felt invisible, and crushingly lonely, and already forgotten.

Yet, I was wiped clean, wiped away. I watched baby translucent orange squid strobe in the murk, and blissfully, as if already dead, I felt quieted.

That night, at the motel, I was alive and I was having trouble sleeping, and trouble thinking. My head was full of the glowing sea crumbs, and I wanted to see them again. I wasn’t sure what to do about this—what I was going to do about this. I’d sweat through the palm-tree sheets, and I got out of bed and did what I do at home to relax in the middle of the night. I opened my laptop and read Emily Dickinson poems. In a desperate and futile attempt to contextualize the day, I searched for one about the sea. I found poem 656, “I started Early – Took my Dog.” There were “Mermaids in the Basement”; “Frigates – in the Upper Floor,” who “Extended Hempen Hands.” The tide made as if He would eat the narrator up, “As wholly as a Dew,” His “Silver Heel” upon her ankle. Her shoes would “overflow with Pearl.”

I began to fade. Soon I was asleep, and I had the dream. Still, my mother stretched out on the orange chaise longue. Still, the propeller plane went down, and the advertising banner chased it, and the beach grass shimmied, and chocolate milk flew from my mother’s thermos. The hotel again burst into flames, and I was pulled underwater. But something was different. Something elusive lurked beyond the laconic eel, though it cast no shadow. Somehow this drowning was the start of something. Maybe my mother’s fingers, once again corporeal, emerging to comb through my hair, as they did when I was a child, but something else, too. Something new. Something old. I don’t know. And when I woke into the humidity of my motel room, clutching the damp sheets, I didn’t know exactly how I was feeling. Maybe I was waning, maybe I was waxing. As if still underwater, I heard my heartbeat, louder than usual. Maybe I was still afraid, but some sort of hand had been extended. Hey: I was still waking up. Outside the window, that was either the moon or a wildfire. The palm fronds, or the woodpecker. Either way, the mermaids were out of the basement, and my mother’s father clung, overflowing with pearl, to their beautiful, dewy backs.