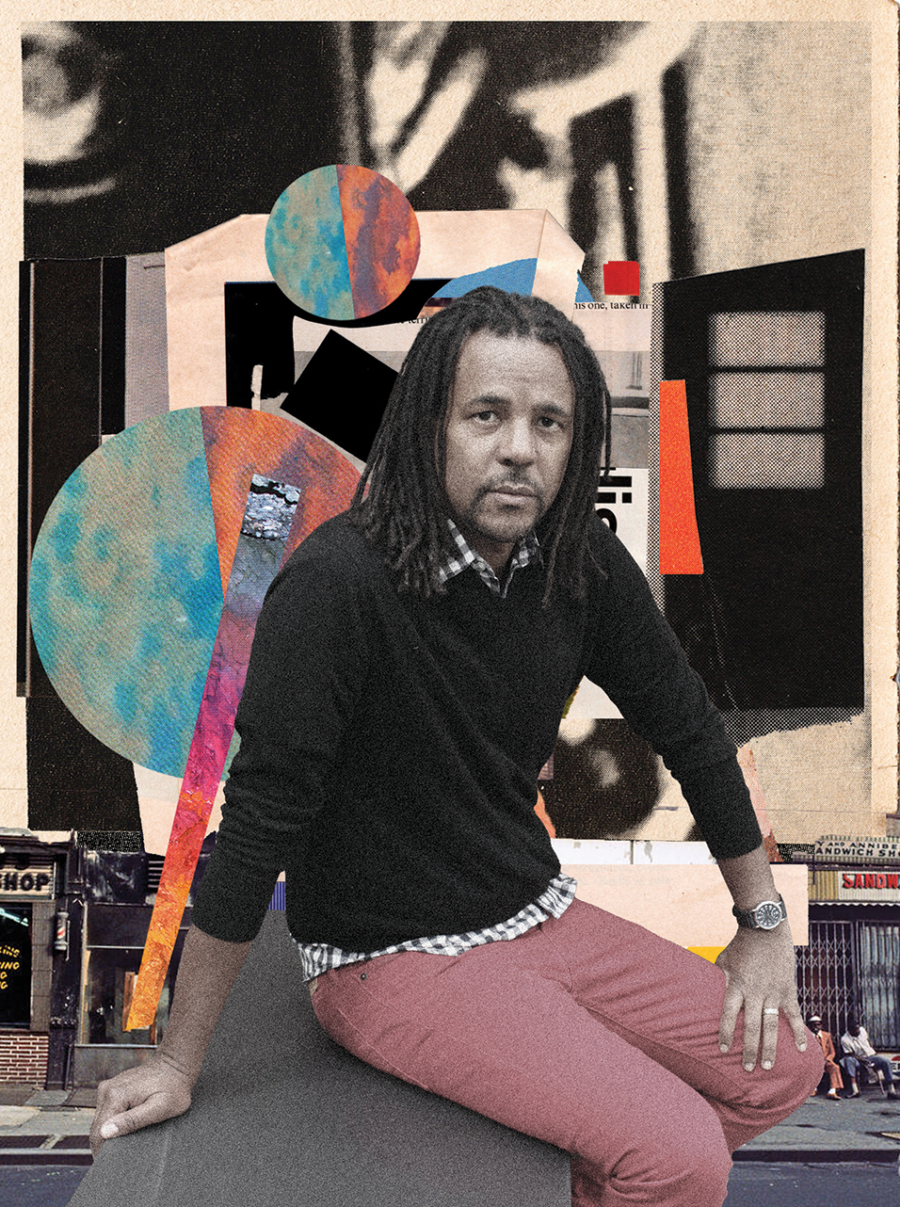

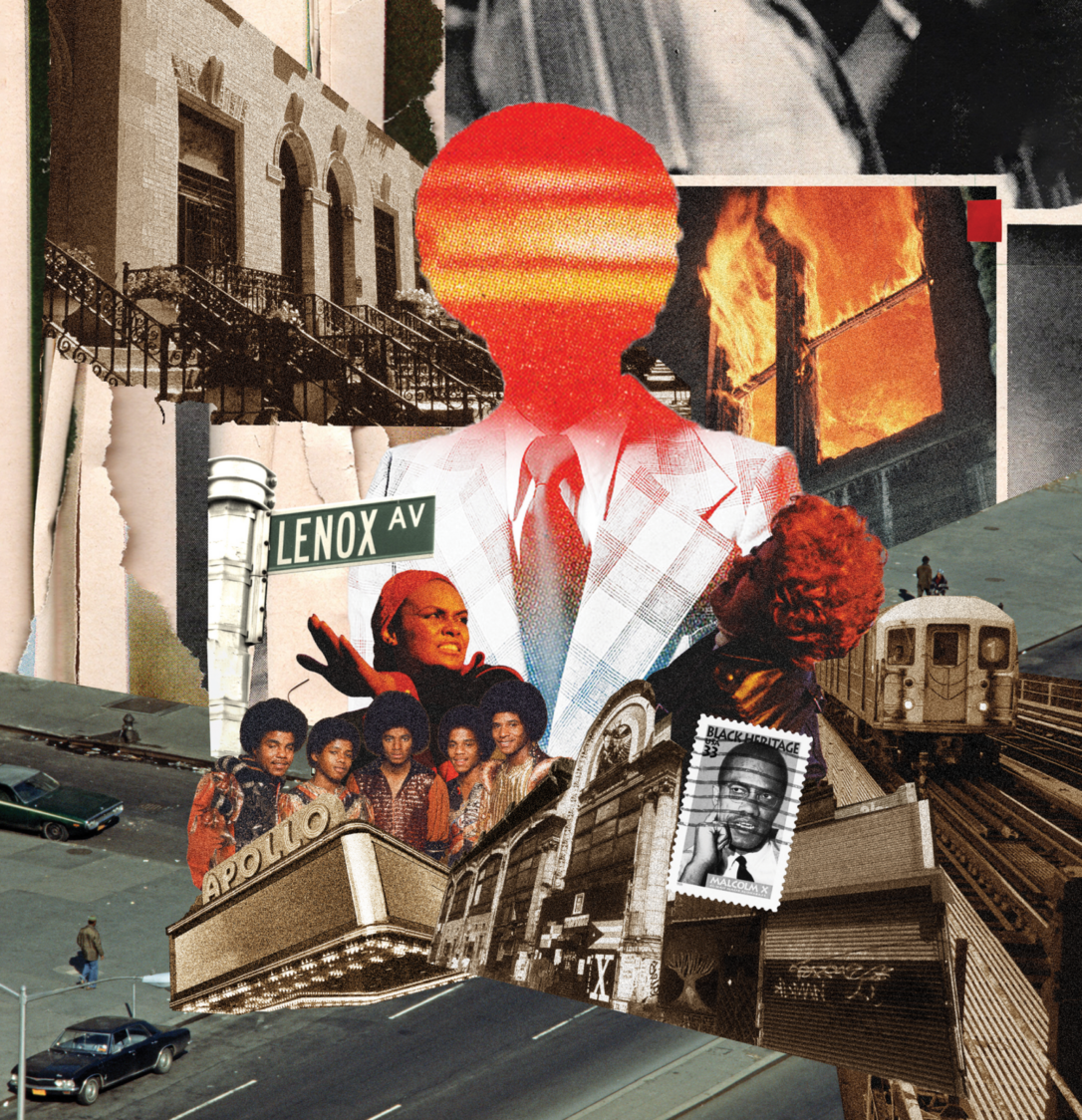

Collages by Dakarai Akil. Source photographs: Colson Whitehead © Basso Cannarsa/Agence Opale/Alamy; Harlem, 1978 © Alain Le Garsmeur/Alamy

Discussed in this essay:

Crook Manifesto, by Colson Whitehead. Doubleday. 336 pages. $29.

Ray Carney, the protagonist of Colson Whitehead’s new novel Crook Manifesto, is a Harlem furniture-store owner and family man. He wants to keep his head down and thrive, but finds it “impossible to play along like everyone else. To pretend that what they meant by freedom was the same thing he meant. As ever, he didn’t fit the templates.” In the words of the narrator, Carney is “just another schlubby shopkeeper getting leaned on.” Or in the even less generous words of a corrupt police detective, “the most famous nobody in Harlem.” Carney’s problem is not so much that he is an anonymous schlub, but that his status as a trader in ill-gotten gains—occasionally fencing stolen goods through his store—hinders his path to the bourgeoisie. He is always trying to separate himself from his outlaw father and the tainted inheritance that founded his business, even as he finds himself struggling to stay on the straight and narrow. A ghetto realist sometimes up against the pampered bougie romantics, he’s stuck and rubbed raw. He embodies the black American contradiction of building a foundation on a surface that holds but also gives way.

Carney is ambivalent about his assimilationist journey from the noisy apartment by the elevated train at 127th Street to better digs on Riverside Drive, until he finally ends up where his hincty wife began: on Strivers’ Row. Toward the book’s close, he agrees to reconcile his crooked and straight parts, like Harlem’s musical tribute to the bicentennial—“folly, fortitude, and that brand of determination that comes from ignoring reality.” At the end, Carney’s furniture store is a bit worse for wear, but we sense a rebuild.

As Whitehead returns to the criminal-as-detective thriller genre with this sequel to Harlem Shuffle, it may be time to start asking whether he’s shorting his considerable skill to appeal to a wide audience. Nearly a quarter of a century ago, Whitehead published his first novel, The Intuitionist, a book committed to high art and high style, the politics of race and the character flaws of the nation. That novel—an ascension story conveyed through a mystery plot—had genre elements of its own, but it was also dense, difficult, funny, and ambitious. Set in an indeterminate era of integration and northern migration, the book starred the first black woman to become a member of the Intuitionists Guild, a group of elevator inspectors who sense the conditions of their units through meditation. The novel turns on Lila Mae Watson’s investigation into an elevator that collapsed in an episode of “total freefall,” an inquiry that pits her against the racists and the rival Empiricists, who rely on rational proof to complete their inspections. Gradually, her detective work uncovers dangerous secrets about the founder of the Intuitionist school, and along the way, Whitehead lampoons the idea of racial uplift and black assimilation alike.

A parody of uplift working alongside a satire of discrimination—as Anatole Broyard might have said, how quattrocento is that? But it is Whitehead’s more recent novels—particularly The Underground Railroad and The Nickel Boys—that have won him prizes and celebrity. These are topical, accessible, driven on by plot, and come with a veneer of progressive race politics. In Crook Manifesto, he’s alert to the misery of the Twin Towers “looming over the city like two cops trying to figure out what they can bust you for,” as well as the “racist face, more Southern Cracker racist than New England Plymouth Rock racist.”

He takes the “burn, baby, burn” anthem of the black militant and tweaks it so that it becomes, in Carney’s words, “churn, baby, churn.” It is, among other things, a reference to the city’s relentless ebb and flow, buildings torn down and new ones raised up, people coming and going. But it also brings to mind Whitehead’s ever-expanding oeuvre: churning the batter, writing a new book every eighteen months, toeing the territory of the market’s conventional earners—Grisham, King, take your pick. Of course, one could argue that these books are examples of what the critic Mark McGurl describes as “meta–genre fiction,” in which

a popular genre—romance, western, science fiction, fantasy and detective fiction—is both instantiated and ironized to the point of becoming dysfunctional in the production of its conventional pleasures.

The easy appeal is that they seem edifying and entertaining in equal measure. But are they? Reading Crook Manifesto, I found myself wondering, was this black culture, “keeping it real,” earned in the only way that matters, which is to say sweating it out with other downtrodden blacks, unmindful of reward? Or was it something else?

I guess it was my KAPsi line brother’s final death and my own private Harlem that interposed. The uptown funeral pulled the fragments back together. Harrison the Harlem Knight on catafalque; Mission from the South Bronx; Big Boy from the Rox; Vark of the Queens Zulus; me from B’More.

Laurie had a bunch of names in his time: he was Harlem Knight before Camp Lo cut wax. He went by Showtime among us Nupes, to the point where even some of his family called him that. His fledgling rap star tag was Kato the Kingpin, groovy to the Jersey Shore crowd he had started to spend time with. His rhymes never got beyond the cassette-tape age. To me he was L Boogie, but his old boy name to his line brothers was Mandingo Crack, which we used to heckle him when his antics went too far. He had something for everybody—like Paul Robeson, an Everything Man.

I hear that era in a metronome of Scott La Rock electronic pulses and tones. I was from Baltimore so I could never understand what anybody was saying, but I was from Baltimore so it wasn’t like it didn’t make sense. Run ’em. Run yours. Get ill. Buggin’. Air it out. Eight ball. Wildin’. Butter. And sometimes the words didn’t even matter. My first time, eighteen on 125th Street and Lenox, it came natural to squat behind the mailbox as the human Harlem Week mass fled the Seventh Avenue gunmen. The next summer there was that riot on the crowded bus with the lady from Trinidad before the boy got stabbed at the Biz Markie and BDP concert.

During the eulogy, Mission told the unvarnished truth about the people we were and had been and the streets and neighborhoods and institutions that gave us our names, chorusing every sentence, “On there.” I thought they must have said it that way in Santiago. After two semesters—pregnancies, guns, dope—my old friends said I was talking like New York. On there and get down. How to tear and fill the cigar. The finger discounts. Umpteen kinds of crook shit. It goes away and comes back. On there and get down.

The crook piece was street knowledge and it had another facet. L Boogie and me meshed with some of the older cats and he had mad deep uncles and the fertile seed began to pop open. He was Showtime and I was the Prophet. Malik Shabazz. Metu Neter. The Cartouche. Red Black and Green. Poor Righteous Teacher. Clarence 13X. Two kufis returned from the Land. Liberation Bookstore. Deeper and deeper into soul music in its modern form, from out of the barrel of a House. L Boogie was a special cat.

To reach Greater Central Baptist we feathered the car between vans on 129th Street. Before we hit the 132nd Street church across from the Lincoln Homes, I overstressed the Easy Mark story to my high-school-age sons. What else is a father to do? A generation earlier I had parked my car in the West Village for a snack, and I hadn’t even noticed that my luggage was stolen until I opened the trunk back in B’More. Specialty crooks went straight to the caboose of out-of-town trains. How hefty were Harlem crooks now? When we got out of the car I slipped the laptop into the wheel well, stymied in my clandestine approach because I had no idea how to operate the electric hatch. Too black for the computer age. Was Harlem the same? The funniest thing Whitehead’s book made me remember about Laurie was the way he would become solemn when he measured things with the space between his hands, declaring something “about yea big.”

In 1974, there were three thousand fires in Harlem and the Bronx. More than a few destroyed buildings and killed residents. The way these fires redesigned America’s signature city, the ties that urban design had to insurance bounties and real estate speculation, are the commanding themes of Crook Manifesto. The novel offers three linked movements to unpack Harlem of the Seventies: the Jackson 5 moment of Michael’s beatification; the acme of low-budget black revolutionary filmmaking distributed by Hollywood and consigned to schlubdom by the NAACP-generated moniker “blaxploitation”; and the decade’s peak at the ambivalently hopeful bicentennial. The three roughly one-hundred-page novellas—each narrated in sparse staccato clips—take the form of adult Encyclopedia Brown mysteries, systematically resolved and feeding on the marrow from their progenitor. 1971: Carney takes a ride with Detective Munson, a bagman for crooked gangsters, to snag J5 concert tickets for his daughter. 1973: Lucinda Cole (shout-out to Baltimore’s own Tamara Dobson), the star of a pyromaniac director’s black liberation film, disappears during a shoot, and Carney’s partner in crime Pepper, a brainy manhandler with a heart, comes to the rescue. 1976: A black blue blood runs for high office, and the heartful slumlord Carney investigates the injury of a child and in the process purifies the temple.

No academic himself, Carney learns the blues of the universe from one of his social betters at the all-black Dumas Club on 120th Street. An attorney named Pierce explains the secret sauce of the RAND Corporation’s deliberately sidelined urban renewal program:

Moynihan’s “benign neglect.” In ’68, Lindsay’s planning commission says it outright—if East Harlem and Brownsville burn up, think of how much money we can save on slum clearance before we redevelop it. Cheaper to let it burn and they can rebuild.

Ray Carney and Pepper put on their capes to target the real bad guys, “the shit,” “prominent lawyers, judges, prosecutors, the heads of insurance firms . . . politicians on the take.” The two outlaws form an aristocracy of crooks, and it’s obvious why Pepper, “a six-foot frown molded by black magic” who ran with Carney’s hoodlum dad, is evoked more deliberately than Carney, the liminal figure between worlds. Pepper is a kind of amalgam of Bigger Thomas and Sonny’s crew from Manchild in the Promised Land. But he’s also from Newark, so he’s a unique combination of hungry, modest, and shrewd, and in this era of Wakanda-the-sequel, he gets to live. Ray Carney is motile and plastic, a self-conscious journeyman who pins his rival, Alexander Oakes, a purer member of the hoity-toity Dumas Club. Oakes, the golden boy who claims a proprietary right to everything that Carney has had to scuffle to get, snubs him in the words of the cigarette ad: “You’ve come a long way.” A comeuppance assured.

But this is part of the meta-joshing. One character satirizes himself when he thinks with nostalgia, “Harlem wasn’t the same. Crooks these days had no code and less class.” A bit later, Carney decides that “in the old days, people looked out for each other in Harlem.” But these sentimental homilies are insincere threads that string into nothing. It’s a nostalgia without an anchor in the past.

Our Harlem Knight had all of the urban skills that make a marvel of a black man. He could run ball, deejay, extemporaneously rap or preach, hit a beat, and lead dancers to the floor. Debonair, he called his children home. He was never at a loss for words, no matter the audience, black or white, rich or poor, urban or country. Town or pasture, it was impossible for him to get lost. Down to the terrain, he always knew the road home. Only a few times did he lapse into “his feelings.” He once jail-learned me to step in time. An intuitionist, he could glean weighty information reading the eyes or scenting the pheromones. He could act a part, cajole and importune, play the heavy to settle accounts, and Romeo his belle. Even though he liked to front rank the apartheid protest, he knew cut from uncut. He came home with me one Thanksgiving and we had a Baltimore Ball, running and gunning up and down the road from stadium to nightclub and fleshy beyond.

We took a picture that night at Club Fantasy and now most everybody is dead.

All source photographs © Alamy. Harlem, 1978 © Alain Le Garsmeur; Cleopatra Jones © Ronald Grant/Warner Bros; Apollo Theater © Erik Pendzich; Jackson 5 © Gijsbert Hanekroot; Audubon Ballroom © Richard Levine; Malcolm X stamp © Alexander Mitrofanov; South Bronx fire, 1977 © Alain Le Garsmeur; Strivers’ Row © Wendy Connett; 125th Street station © Richard Levine

The Jackson 5 notwithstanding, Whitehead’s is essentially a pop affair, denuded of “The Sound of Philadelphia,” the Salsoul Orchestra, or post-Gordy-leash Motown. His sonic world does not lead to the commanding female vocalists in the bottom of the Seventies, the sounds of “Funkin’ for Jamaica,” “Any Love,” or “Got to Be Real.” Perhaps this is part of the goal, the crook shot, the pop music is the base that fakes us all together. Crook Manifesto has no granular reveries to soul food delicacies or ritual encounters with bookish black nationalists of the Elder Michaux variety. No John Henrik Clarke or Ms. Sybil. No Mary Lou Patterson checking in on her parents between Cuba and the Soviet Union, or Keith Gilyard and Jean Blackwell Hutson amused by Baraka’s flight to Marx.

He does silently affirm Albert Murray, that proud humanist philosopher of the blues, who perched for so many years on 132nd Street. Murray decided in his 1976 colossus Stomping the Blues that the blues idiom reflects

a disposition to encounter obstacle after obstacle as a matter of course. . . . Indeed the improvisation on the break, which is required of blues-idiom musicians and dancers alike, is precisely what epic heroism is based on.

Break improvisers. Ray Carney and Pepper, blues steppers to a T.

My grandmother and her sister, redbone country girls, lived in Harlem in the Twenties, and Aunt Daisy married a mysterious Dominican who drowned. The sisters returned briefly to the tobacco farm, then scooted up to Baltimore. My parents first saw New York as Morgan College students ushered to Broadway by their drama teacher. They took me to see the Rockettes around 1973, and my Dad probably didn’t once think of a ride uptown in one of those cabs with the nifty folding seats in the middle of the floor. Everything smelled like roasting chestnuts.

Last year, I took a few students from Baltimore to Harlem to see the sights in the wake of our Malcolm and Martin seminar. The Audubon Ballroom, Edgecombe Avenue, Strivers’ Row, the Schomburg Center, Sylvia’s, the Apollo. First-class tourist play. Only three students came, since the class was unpopular (three hundred pages of reading a week). In an avuncular way, I tried to coach them about what might lie ahead. Dress down. Fit in. Closed-toe shoes. I wore a red Ivory Coast shirt so I would be visible on a crowded subway. One student, hair like Shaun Cassidy in the Seventies, appeared in a T-shirt with the school name emblazoned on the front and carried a heavy duffel bag by its hand straps so that all the world would know.

We surprised ourselves by getting inside the Audubon Ballroom, closed on account of the virus, but opened up briefly at the custodian’s discretion. He was my age, and I talked to him about a neighborhood legend who had meant something to Laurie: Alpo, the Harlem kingpin who was also credited with kicking off that famous Virginia Beach civil-rights march of 1989. I slipped him a twenty-dollar spot of thanks, then trooped down Eighth Avenue, heading east at 155th Street.

As we approached Laurie’s buildings, the Polo Grounds, I was telling the students about Jackie Robinson and the Dodgers. We halted at the light for the dash through the intersection to 409 Edgecombe. And it was at that moment that two old boys from down the hill materialized on scooters.

Decades ago, Mission and I had come to L Boogie’s tower by the viaduct on the north side. Laurie and I used to get lifted and fight each other in college, sometimes breaking stuff, the last time over a young Puerto Rican woman. L Boogie was Mandingo-strong but had played basketball. I was slim but had wrestled. We measured each other. I gave up a shoulder trying to keep up with him on the rugby field. Laurie’s homeboy Shaun was killed in summer of ’89. My homeboy Donald was killed in summer of ’89. We carried our city scars back to campus.

Whatever, on there, I associated some heart with hustlers from the Polo Grounds.

As I inserted myself between my students and Harlem’s Angels, I got a full view of their team. The boys looked like characters from a Chester Himes tale. Without benefit of soap or sleep for days. Ski-masked, all rusty black gear, creepy facial and hand tattoos. One boy thick, the other tall and wiry. The lanky boy had a lot of sleep in his lined eyes, and at the hillcrest they said something to each other. This pair didn’t seem prone to waiting at the light. In fact, they looked like a crook duo hitting licks, if they could get their dingy bikes to jet away. The tall boy went into his dip and I did think, Good God is it really going down? The glue set around my toes in the same way it always does when I am about to get ran.

He sparked a blunt. On to Du Bois and the plaque at 409.

Down the hill from Edgecombe I reward the students with frappés at a café that has, seemingly, only white patrons.

Whitehead has always shown a meticulous interest in the forces underneath, the undertow, the chthonic subterranean, as a way of getting at the terra firma, the three-billion-year-old plates strong enough to bear the weight of the city. In Crook he plays with schist, the platy rock that wedges up from the earth and serves as a foundation. In essence, the slow process of the plates cooling to bedrock, like the evolution of biological life itself, responds to an activity of unsettlingly imponderable and cataclysmic scale. From burn to churn.

Churn, baby, churn. Atop the unchanging schist, the people replaced each other, the ethnic tribes from all over trading places in the tenements and townhouses, which in turn fell and were replaced by the next buildings.

A crook with a heart of gold, Ray Carney gets outside of himself, beyond the buildings, and sees the horizon.

What are the forces that make sense of the churning sequences, and to what place does the writer of note deliver his audience? What’s the juice of this squeeze? By its nature the genre convention delivers lovable punch lines. His coke-fueled comic survives to star in a movie called Chimp Cop. The acetylcholine buildup in my brain had my mouth watering for a tinny pop song, the one that as a child you had no defense for and would just seep into you, and, on cue, Whitehead thumped out with Starland Vocal Band’s “Afternoon Delight.” The niche historical reference to the 1943 riots and giving “the Blitz”—rocks, bricks, bottles, and shots—to cops who richly deserved it. Nice. And the weighty allusions to the schist, the foundation for the Manhattan he adores and the money-grubbers who move there to worship at its shrines. And there’s a didactic peak, a lot like a lyric inked by Ta-Nehisi Coates, Michelle Alexander, Nikole Hannah-Jones, and Richard Rothstein:

The white people take advantage of those new highways out to the suburbs and flee the city into homes subsidized by federal mortgage programs. Mortgages that black people won’t get. And the blacks and Puerto Ricans are squeezed into smaller and smaller ghettos that were once thriving neighborhoods. But now those good blue-collar jobs are gone. Can’t buy a house because the lenders have designated the neighborhood as high-risk—the redlining actually creates the conditions it’s warning against. Unemployment, overcrowded tenements, and you get overwhelmed social services.

It just goes from bad to worse. What had seemed a defiant burning is really a finance-insurance-real-estate neoliberal transmogrification. The crooked pols and wags unleash the arsonists to churn dollars to development. It’s difficult to imagine the Whitehead of The Intuitionist writing so earnestly about a condition obvious since—1976! Give the people what they want, true. But knowing what we know, laughing when we are primed to and nodding our heads in unison corresponds tidily to the blown-out brownstone with the Elizabeth Roberts glass wall: We are entertained and informed and still bent on making it in New York. That’s the Crooklyn that makes us all a crook.

Whitehead’s book does have glimmers of promise, of something irreducible to the social, the reason you read a novel instead of a pamphlet on segregation. But the resolution, connected to a gauzy nostalgia, is yet another aspect of the inevitable limit, the containment of genre fiction. The book’s wisdom operates in hindsight. Twenty-four years ago, we might have claimed to have been discomfited from habit or pricked into thoughtfulness by The Intuitionist. The best that can be hoped for now is that we’ll laugh and sneer at being entertained with the history we should have known.

L Boogie took it pretty far. After we stepped with the Jungle Brothers at the concert in Bridgeport, he hooked up with the New York City Step Team and he and Mission did the Biz Markie “Just a Friend” video. Then my right-hand man from Baltimore remembered him from the Thanksgiving blaze and wrangled him in front of the camera with Chubb Rock, “Just the Two of Us.” High Cotton.

L Boogie had wanted to write the historical romance of the Base Nigger. My misfiled senior thesis was titled “Son of a Motherfucker.” He was always riding me to get up on the marquee. I thought he was tripping, so when the public safety officers responded to the noise complaints at our house I would give them his name. He was a student trustee and would go to the diplomatic councils in the weeks before the president’s office was firebombed. Then he would go out on the lam with his roscoe. Donald and my dad had just passed away so I took myself to another place. Damn sad about revolutionary Nick Haddad.

But who knew what to do with all that marvel? Mission would put on the 5-0 blue and Big Boy climbed up the ladder. L Boogie channeled his energy first into the art, then the weight room and bringing up his nephews, the way his uncles had done with him. Not too many ways to make moves and it started to shake both of us apart a little. Later it shook L Boogie a lot, the stance between burn and churn. The corrupt politicians, the rigged prison system, and the hard streets. The framework of housing and urban planning and bank loans that held us down and that we read about in How Capitalism Underdeveloped Black America. Every cat who said they wanted to go to law school or earn an MBA seemed like a fat sellout. Everyone who said they wanted to be a teacher or a social worker seemed like a sucker. It all takes a toll. I know Laurie wearied of playing cock diesel that night he dipped on my man and let him get banked. So he would shout on the subway and shout in the police precinct. He shouted whenever it felt good, whenever it seemed like the right thing to do.

Forty or fifty of us sang our hymn. And it was the only live choral music at the funeral, on there, at 132nd Street. A brother put a funereal step-show cane, taped in white, in the casket. Elegant touch. I slipped in a .38 shell. Draped like Prempeh, Harlem Knight took his final bow at the cemetery across the river, next to his Nana. His surviving Harlem homeboy spoke about growing up on 148th Street, before they got to the Polo Grounds. I remembered L Boogie’s story about losing the nub of his finger in the door. He had a way of keeping his hand. It never crossed the mind, that trace of him left on the threshold.