Joe Biden campaigning in Portsmouth, New Hampshire, July 12, 2019 © Devin Yalkin

For decades, New Hampshire has generated brisk and gratifying drama with its first-in-the-nation presidential primary. The Granite State momentously destroyed a presidency in 1968, when the Minnesota senator Eugene McCarthy ran against President Lyndon Johnson on an antiwar platform. Johnson had been so confident of his renomination that he had not initially deigned to enter the New Hampshire race, while other leading Democratic politicians, including Robert F. Kennedy Sr., remained aloof, fearful of challenging the president despite his mounting unpopularity during the Vietnam War. Thus, McCarthy was the only major Democrat on the ballot. When the fervor behind his campaign revealed the senator’s surging support, Johnson hurriedly mobilized a write-in effort, which duly yielded him a 50 percent share against McCarthy’s 42—a poor enough showing for a sitting president to embolden Kennedy to enter the race four days later, and for Johnson to announce his retirement from the race two weeks after that.

For Joe Biden, the New Hampshire primary’s history is entirely hateful. In 2020, the contest came close to terminating his hopes for the White House. Running out of money, his staff deflated by the results in Iowa, his public image scarred with mishaps (including an unpleasant jibe in which he called a questioner a “lying, dog-faced pony soldier”), he finished fifth, with just 8.4 percent of the vote. Fleeing the state before the polls closed, he moved to the more congenial territory of South Carolina, where black voters, generally his most dependable constituency, set him on the path to the White House.

Small wonder, then, that Biden has done everything in his power to ensure that New Hampshire has no chance to make history again, at least not while he is running. Last December, he urged the Democratic National Committee to rearrange the primary calendar so that “voters of color have a voice in choosing our nominee much earlier in the process.” It was clear that he meant South Carolina; two months later, the DNC formally obliged, and the state will vote on February 3, 2024. The DNC justified the change by arguing that it gives black Democrats a weight in nominee selection proportionate to their importance as Democratic voters; it also fits into Biden’s overall electoral strategy, which hopes for a rerun of 2020 without the irksome bits, including any nomination challenges from his own party, leaving him free to run as the lesser evil against Donald Trump.

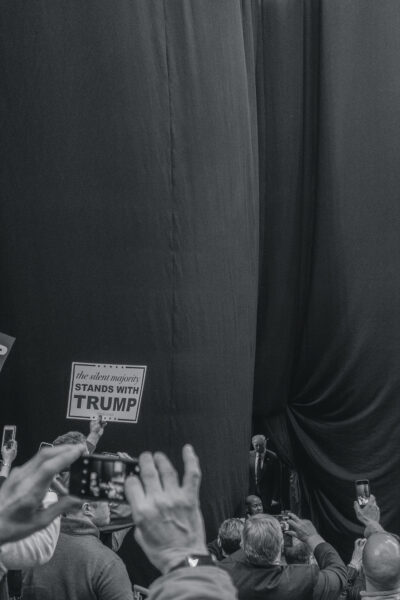

Donald Trump campaigning in Manchester, New Hampshire, February 8, 2016 © John Tully

Trump, at least, is playing his part: maintaining his lead as the Republican front-runner, even while accumulating indictments. That would bode well for Biden, were it not for the polls’ persistent indication that he is hardly more popular than his Republican rival. Despite low unemployment and an apparently prospering economy, Biden leads his likely opponent by the thinnest of margins, while his approval ratings bump along in the low forties—only barely cresting Trump’s own average over the course of his presidency. Despite strenuous efforts by his handlers to project an image of a sharp and focused president, the widespread perception of senility prompted by Biden’s stumbles (such as the declaration that Putin “is clearly losing the war in Iraq!”) seems to stick in voters’ minds. Even among Democrats, most of whom like Biden, the majority would prefer he not run at all.

But New Hampshire’s lead spot is not merely a matter of hallowed tradition; it is enshrined in a state law that mandates the primary election date be at least one week ahead of any other state’s contest. Since the legislature and governor’s office are both controlled by Republicans, that almost certainly will not change. It is doubtful that Biden will participate in a party-defying New Hampshire vote sometime in late January. Barring a successful write-in campaign, as Republican governor Chris Sununu commented, “someone other than Joe Biden is going to win the first-in-the-nation primary.”

Downplaying the state’s role may be a wise precaution for the Democrats, given potential discontent with Biden’s regime there. While superficially prosperous, the state’s economy is suffering from soaring electricity costs, a severe lack of affordable housing, and labor shortages driven by an exodus of young people, along with the disappearance of older workers who did not return to the workforce after the pandemic. “These issues were already building,” Rich Gulla, president of the New Hampshire branch of the Service Employees International Union, told me. “COVID broke the dike.” Gulla’s powerful local has so far declined to endorse Biden, announcing in April that “his record and actions” do not warrant their support:

We need a President who will champion a significantly higher minimum wage, the PRO Act, Railroad workers’ right to strike, Starbucks workers’ right to organize and truly all working people’s rights to a living wage.

The situation in New Hampshire theoretically leaves room for anyone to enter the fray. But chances for any such intervention by established and electorally successful Democrats—such as governors Gavin Newsom of California, J. B. Pritzker of Illinois, or Phil Murphy of New Jersey—seem slim. All three have displayed signs of mulling a presidential bid: Newsom made a splash with visits to red states; Pritzker “halfheartedly,”according to the New York Times, denied interest in a 2024 White House bid; allies of Murphy set up a national fundraising PAC. But all such ambitions have come up against the barrier of Biden’s unwavering determination to run, whatever the polls may say.

Should the president be forced to step aside, the field will open, in which case Michigan governor Gretchen Whitmer will certainly be a central object of speculation. The attractions for mainstream Democrats are obvious: her unstinting loyalty to Biden, her role in turning Michigan blue in 2022, her progressive record on abortion and LGBTQ rights. She has also followed through on traditional Democratic objectives like repealing the “right to work” laws that repress organized labor. She offers an enticing alternative to Biden’s putative but similarly unpopular heir, Kamala Harris, who manages to display incoherence equal to Biden’s without the excuse of senility. Tellingly, in early June, Whitmer formed the Fight Like Hell PAC to help Democrats hold the White House.

Even so, there is little prospect of an establishment figure daring to challenge the incumbent, whatever his deficiencies. So long as Biden refuses to step aside, any Democrat venturing to run in New Hampshire and beyond must be an insurgent, willing to campaign against the current Democratic administration. Given the specter of Trump as the probable Republican nominee, such a figure can expect a hostile reaction from mainstream liberals.

The belief that insurgent candidates, and the movements they generate, are never more than dangerous impediments to Democratic electoral prospects is deeply rooted in party orthodoxy, nurtured by the belief that previous outside challengers have sabotaged the party’s chances.

Ralph Nader in 2000, running on the Green Party ticket, and Bernie Sanders in 2016 both campaigned on themes of protest against the dominance of corporations and special interests. If nothing else, these efforts served as convenient scapegoats for the Democrats’ losses. Nader ignited enduring rage for allegedly electing George W. Bush by siphoning a vital margin of votes from Al Gore in Florida. (He in fact drew votes from both Gore and Bush.) But the columnist Jim Hightower has argued that the loss of 308,000 traditional Democratic voters to Bush was the fundamental cause of Gore’s defeat. Hightower ascribed the departure of these supporters as an inevitable reaction to Bill Clinton and Gore “adopting the policies of the corporate and investor elite,” thereby shedding the party’s core populist constituency. Sanders generated a similar establishment reaction for his audacity to challenge Hillary Clinton in 2016, supposedly arousing supporters who ultimately voted third party, for Trump, or not at all, while himself giving only tepid support to the eventual nominee. Again, a more sober analysis indicates that these charges are largely groundless. While there were manifold explanations for Clinton’s loss, notably the many million estimated 2012 Obama voters who switched to Trump, there is scant evidence that defecting Sanders voters was one of them.

The view that party challengers have no place running on a Democratic Party platform has been conveniently summarized by Dmitri Mehlhorn, an influential figure by virtue of the millions he spends on campaigns; he’s also a political adviser to the tech billionaire and Democratic megadonor Reid Hoffman. “Far-left groups,” Mehlhorn told CNBC in 2022, “help the MAGA movement by attacking centrist Democrats who can win general elections.” (Mehlhorn’s statement seems disingenuous, since Hoffman has spent heavily to defeat progressive candidates in blue districts where a Democrat was almost certain to win anyway.) Mehlhorn is determinedly of the view that people can only be motivated by fear: “You cannot get people to vote by getting them to believe that voting and participating will materially improve their lives,” he told Ryan Grim of The Intercept. “What you can get people to get really excited about is: ‘If you participate in politics, you might be able to prevent something really bad from happening to you.’ ” This theory evidently finds fertile ground in the Democratic camp, where Trump’s probable nomination as the Republican candidate is reportedly viewed with joyful expectation as a certain path to victory for the incumbent. As one Democratic strategist told me: “It will be America versus MAGA.”

The flaw in Mehlhorn’s argument, or one of them, is that for many Americans, “something really bad” is already happening. Nearly 10 percent have significant medical debt. Millions must work two jobs to make ends meet. More than half of Americans say they couldn’t get their hands on $1,000 in an emergency. An August 2022 analysis found that more than one in four feared imminent eviction or foreclosure. Around 10 percent of student debtors default in their first year of repayment—a number that will likely increase following the Supreme Court’s rejection of Biden’s initial timid relief initiative. Many of these conditions were in place under Clinton and Bush, especially as manufacturing jobs moved overseas, but the 2008 financial crisis and the pandemic have inflicted traumas on American society that will play out for years to come. Close to ten million Americans lost their homes in mass foreclosures around the Great Recession, and homeownership levels have yet to recover. The ongoing housing crisis is also visible in the homeless encampments of West Coast cities such as Los Angeles, San Francisco, and Portland. And school closures in 2020 tanked the education of a generation of children. Across the nation, reading and math scores sank, while teenage depression soared. Pandemic-era borrowing exploded government debt, inflation reached levels unseen since the Eighties, and major banks failed. A recession could land in good time for the 2024 election.

Bernie Sanders campaigning in Warner, New Hampshire, May 27, 2019 © John Tully

Such a state of affairs inevitably opens a breach for a radical initiative. Currently on offer are the Democratic candidates Robert F. Kennedy Jr. and Marianne Williamson, as well as Cornel West, who is running on the Green Party ticket. All three present vehement critiques of the status quo in different shades of progressivism. West is by far the most unequivocal in his denunciation of the Democratic and Republican parties as dominated by big money and corporate wealth. He is no less emphatic in his condemnation of Israeli occupation and domination of Palestinians, and in his condemnation of the militarization of American foreign policy. Democratic leaders seem to fear that he might siphon off just enough black and leftist votes from Biden to give Trump a winning margin. Meanwhile, the challenges to Biden by Williamson and Kennedy, however quixotic, have dominated the headlines.

“The election in 2024 cannot center around warning people about Trump,” Williamson told me when we talked in her Washington apartment in May. “If that’s what we’re doing, we will fail. The win in 2024 will come from offering the American people a better deal, an economic new beginning.” Her speeches come with copious examples of the nation’s ills, accelerating inequality and rising medical debt among them. She stresses that tens of thousands of Americans are dying each year from inadequate medical care, and over half of Americans are living from paycheck to paycheck. We must consider “not just numbers,” she says, but the “human lives in despair.”

The establishment response has been predictably unwelcoming. Williamson was ubiquitously derided during the 2020 campaign as “kooky” and “all but loopy,” sneers that have followed her into her second run. She nurses bitter feelings of her treatment as an outsider intruding in a professional politicians’ playing field, especially during the 2020 Democratic debates. “Every time I saw Amy Klobuchar, she would say to me, Are you having fun? That was all she ever said,” Williamson told me. “Every time I saw Pete Buttigieg, he said, Are you having fun yet? . . . I didn’t realize how much like high school the whole thing would be.” As she observes, Vivek Ramaswamy, a wealthy GOP candidate with no political experience, who supports invading Mexico and raising the voting age to twenty-five, has been the subject of numerous mainstream media reports, while she struggles to make her voice heard. The press she does receive tends to focus on her admittedly high staff turnover. Nonetheless, she has been polling just as well, or better, in her party than any candidate, apart from Trump and DeSantis, has in the GOP.

Kennedy does not struggle for attention, though his coverage tends to verge on the hysterical: “Robert F. Kennedy Jr. Is a Lying Crank Posing As a Progressive Alternative to Biden,” declared Current Affairs, summing up mainstream attitudes. Critics chronicle his support from conservative figures like Tucker Carlson and Elon Musk, not to mention the enthusiastic comments he has received from Trumpian devil-figures Steve Bannon and Roger Stone. His denunciation of mounting U.S. involvement in Ukraine might be enough to damn him in the eyes of orthodox opinion, especially as it is echoed by Trump and a portion of the congressional Republican party. His enthusiasm for bitcoin (dubbed “rat poison squared” by Warren Buffett) can only bolster his reputation for eccentricity. But it is his vociferous denunciation of the pharmaceutical industry that has evoked the most fevered response among Democratic Party stalwarts, an onslaught replete with characterizations of him as “crazy” and “unhinged.”

“Nobody in the Democratic Party talks to me,” he said cheerfully when we met in Georgetown early in his campaign. “I’m a pariah.” It’s doubtful that anyone running against the party leader and scoring up to 20 percent in the polls, as Kennedy has done, would get any kinder reception. Although his critique of health policy, deeming it under the control of the pharmaceutical industry, is extensive and detailed, his position on childhood vaccines and their possible link to the dramatic increase in autism—from 1 in 150 eight-year-olds in 2000 to a staggering 1 in 36 in 2020, according to the CDC—has earned him obloquy extending far beyond mere partisan rancor. His repeated protestations that he is not opposed to vaccines as such have made no difference. (Solicitous of my professional welfare should I stray into vaccine-denial territory, he advised me kindly: “You don’t want to talk about that.”)

Kennedy’s platform is replete with disparate positions, such as pledges on the core progressive issue to support environmental protections, a deference to the Second Amendment, and a demand that the Southern border be made “impervious.” He draws inspiration on border protection from Israel, which he says “has the same issue with refugees coming in from Africa,” but has opted for “monitoring systems” rather than a wall. His repeated expressions of fealty to the Jewish state, even as the Democratic base drifts away from its traditional allegiance, had shielded him from some establishment assaults. During a discussion at a New York dinner party in July, however, Kennedy reached into his congested memory bank of scientific literature and aired the questionable view that COVID-19 was “targeted to attack Caucasians and black people,” while “the people who are most immune are Ashkenazi Jews and Chinese.” Such musings were enough for him to garner charges of anti-Semitism, most vocally from leading Democrats, who moved—unsuccessfully—to prevent him from testifying before a congressional panel at the invitation of House Republicans.

Nevertheless, the bulk of Kennedy’s positions fit the mold of what used to pass for a liberal Democrat: assailing corporate power, the military-industrial complex, foreign wars, and censorship—positions implicitly abandoned by an administration that is committed to the Ukraine war and increased military spending. “Why are liberals now in support of war?” he lamented to the Wall Street Journal. “Why are they suddenly in support of censorship? Why are liberals suddenly putting faith, ultimate faith, in pharmaceutical companies, who have always been great villains in the liberal zeitgeist?” The Democrats’ abandonment of such liberal values, he believes, has been coupled with the loss of its populist base. Citing the record of his murdered father, who on the penultimate day of his life won primaries in both urban California and rural South Dakota, he believes he can reverse that trend. “The people who lined the train track when we brought [his casket] to Washington were every color of the rainbow,” he said, noting that nearly four years later the racist Alabama politician George Wallace garnered significant support in the Democratic presidential primaries before he, too, was shot and exited the race. “What I want to do,” Kennedy continued, “is bring those people back into the Democratic Party with a vision of idealism for this country.”

Kennedy believes that the increased inequality that accompanied the government’s pandemic response—“it was a gift to the superrich”—is the issue that will give him an edge over Trump. “I’m stronger against Trump than anybody because I can make the argument about the lockdowns,” he told me. It was Trump, he points out, who oversaw the pandemic measures resented by many. “In the last three years,” he told the New Hampshire Senate in June, “there’s been an all-out assault on the Bill of Rights” with our “government participating in censorship of political dissent, of people who are criticizing federal policies.” Among those listening with keen approval in the chamber was twenty-year-old Jonah Wheeler, a Democrat from Peterborough elected to the state house in 2022—who beat an incumbent Democrat. He campaigned on the idea that “our country is being taken over by corporations, that the working-class people of New Hampshire are being shafted at every level.”

“There were more angry people in this town than I thought, people who hadn’t voted in forty years, people who had turned off the system,” Wheeler told me. Hence his positive reaction to the insurgents. “I think Kennedy and Williamson are the only people who can beat the fascist,” he went on. “Because they can tap into that anger, that discontent that someone like Trump can tap into, but in a real and genuine way that actually addresses their anger in a coherent, thought-out vision.”

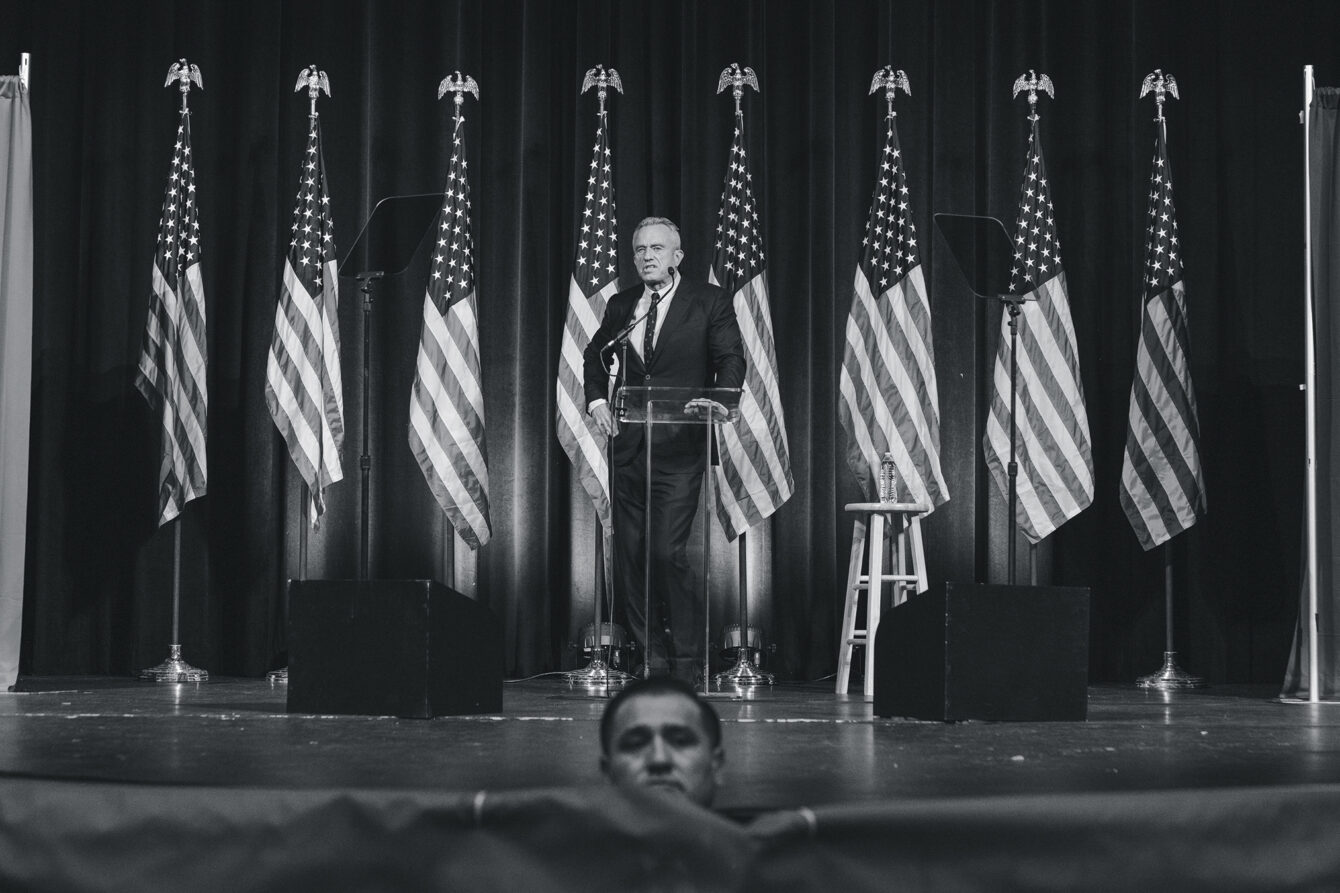

Robert F. Kennedy Jr. campaigning in Goffstown, New Hampshire, June 20, 2023 © Sophie Park

At times, Kennedy has enjoyed net favorability ratings well ahead of any candidate in either party. Nonetheless, it seems likely that the torrent of negative coverage he evokes will derail his chances of success. Biden’s shirking of New Hampshire may be offset by unofficial efforts on the president’s behalf. “If the only names on the Democratic primary ballot will be Robert Kennedy and Marianne Williamson, I will write in ‘Joseph Biden,’ ” Jim Demers, a prominent New Hampshire Democratic lobbyist, told me, reflecting adamant unhappiness with the choices on offer. Insurgent success in New Hampshire may be further obscured by the drama of the concurrent Republican contest, with its multiple challengers to Trump. In those cases, any threat to Biden’s prospects, mirroring McCarthy’s terminal blow to Johnson, will likely fade away.

Yet even if the challengers fail, their efforts could have lasting consequences. In 1992, Pat Buchanan, then a prominent right-wing columnist and TV commentator, ran for the Republican nomination against the incumbent, George H. W. Bush. His message, replete with denunciations of an establishment out of touch with ordinary Americans, proved potent enough to make him a relatively close second to Bush in New Hampshire. (He went on to score almost three million votes in the general election.) He also earned a prime-time speaking slot at the Republican convention that summer. He used the chance to declare “cultural war” for the “soul of America,” against an enemy of radicals “cross-dressing” as moderate Democrats, who were preaching “abortion on demand” and “radical feminism” while working-class Americans watched their jobs disappear and a “mob”—the Rodney King riots—looted and burned Los Angeles. The liberal columnist Molly Ivins memorably wrote that the speech “probably sounded better in the original German,” but its themes would form the founding document of today’s Republican Party. Indeed, when I mentioned the speech to a former Trump Administration official, he immediately recited several lines by heart.

The continuing influence of Buchanan’s message, now deployed by Trump, has paralyzed politics in America, given the Democratic priority of preventing another Trump presidency—and the reluctance of the left to fight back with its own insurgents. Hence, in the 2024 general election, there will likely be little or no discussion of the existential crises confronting American society: racism, chronic diseases, militarization, war, and the threat thereof. (Cornel West’s campaign may survive through to the election, but the pressure to stifle his arguments will be immense.) This depressing situation at least highlights the fundamental problem of a system in which power is centralized in the presidency, so that all politics are ultimately subsumed into a binary contest. Once again, we’ll have the great democratic privilege of voting for the lesser evil. In that race, no one gets to write in.