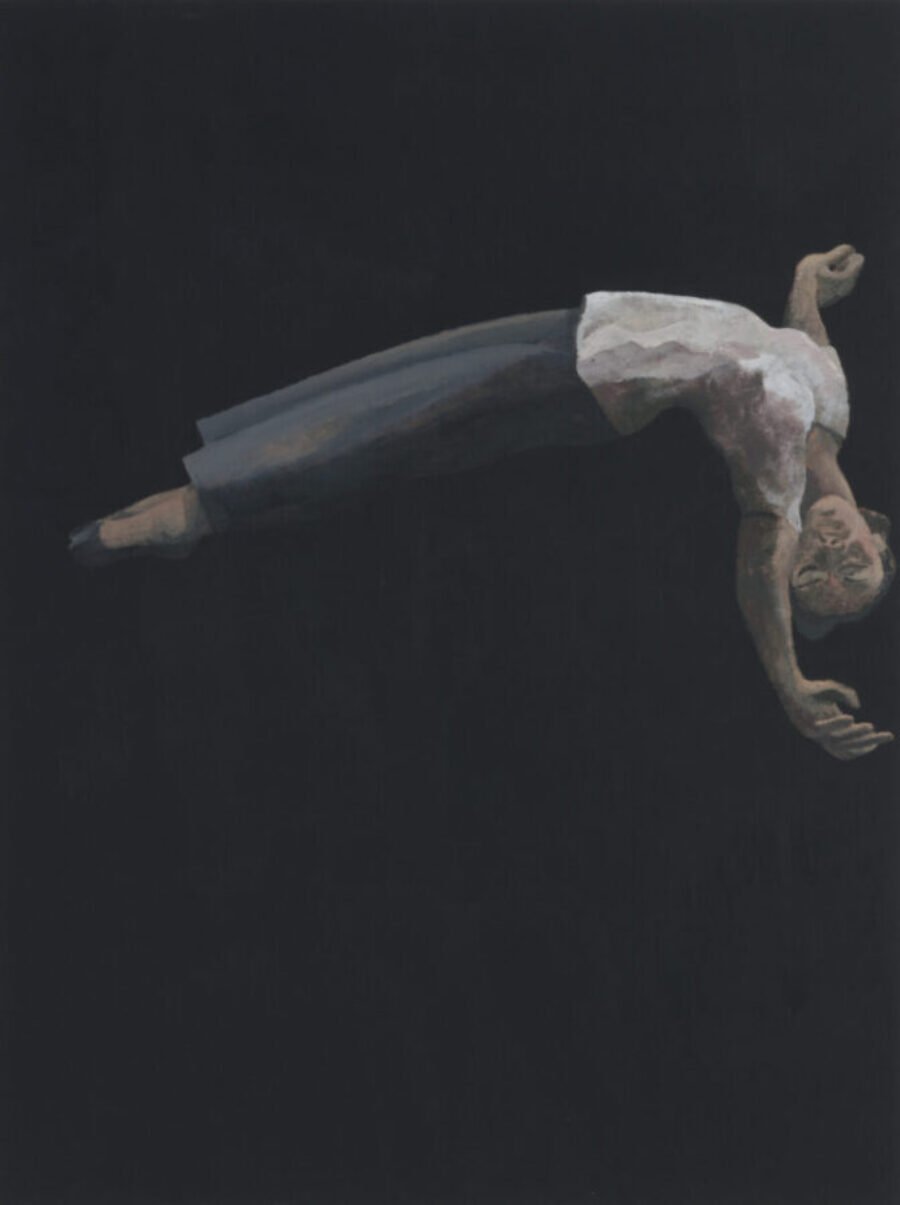

Intrusive Thought, by Lenz Geerk © The artist. Courtesy the artist and Roberts Projects, Los Angeles

Not long ago our mother died, or at least her body did—the rest of her remained obstinately alive. She took a considerable time to die and outlasted the nurses’ predictions by many days, so that those of us who had been summoned to her bedside had to depart and return to our lives.

No one cried at her death, though among the congregation at the funeral there were some outbursts of shocked weeping, as though at the sight of death being surprised in the act of stealing from life. It was the entrance of the coffin, rather than the death itself, that constituted the violence of this act. The coffin was shocking, and this must always be the case, whether or not one disliked being confined to the facts as much as our mother had. The body inside the coffin was entirely factual. She had never seemed to take much notice of her body: it had been her vehicle, that was all. But its authority, it turned out, had been absolute.

For a while afterward there was a feeling of lightness—a feeling almost of freedom. The violence of death had the appearance of a strange generosity. A capital sum had been returned to the living: we on the side of life had been in some way increased. But in fact an unease remained, which grew and which was our mother’s impenetrable bequest to us. There ought to have been a feeling not of freedom but of loss. If there was loss, then it was of something we had never had. We were free simply from the conundrum of this double loss.

It was noted that at the funeral we had remained unmoved. It was a day of extreme, almost frightening heat, like the day of Meursault’s mother’s funeral at the beginning of Camus’s The Stranger. Meursault’s seeming indifference that day was also noted: it later became a central piece of evidence in his trial and conviction as a heartless killer. Was our indifference likewise a philosophical refutation of the social contract? Had we too run the risk of being arrested and convicted for the failure to adhere to cultural and moral narratives?

Months later, at dawn on the ninth floor of a hotel in The Hague, standing before a view of astonishing ugliness, it became evident that our mother was accompanying us in a way she had not when she was alive. Far below people scurried across the concrete spaces in the cold gray morning. A violent wind was blowing. It shook the power lines and the leafless trees. It rattled the hoardings outside the shop fronts. It upended the litter bins and sent their contents whirling madly into the air.

The mother of the filmmaker E did not know who her son was: his name, which had become widely known, was not in fact his real name. He had assumed it so that she should not discover what he did. While she lived she knew nothing of his illustrious career, and even after she died he maintained this alias and the habits of secrecy and disguise that came with it.

His films were naturalistic and poetic, and his mother might not have found much in them to disapprove of, but he would not have been able to create them in the guise of himself. Yet what was perhaps most unusual about them was that they were always instantly recognizable as his. His style, so uninterfering, drew attention to itself without meaning to. He rarely, for instance, showed his characters in close-up, believing that this was not how human beings saw one another. His films had no particular aesthetic. They often took place in public spaces, and his characters seemed barely to notice that they were being watched. They wore ordinary clothes and rarely looked at the camera. They were absorbed in their own lives.

For those accustomed to the camera’s penetration of social and physical boundaries and the strange authority of its prying eye, this absence of what might be called leadership was noticeable. People were often baffled or even angered by his films. They expected a storyteller to demonstrate his mastery and control by resolving the confusion and ambiguity of reality, not deepening it. Even the more radical filmmakers among E’s contemporaries at least gained respect through the boldness and assertiveness of their artistic vision.

E’s family lived in a large house in a bourgeois country town, and this is where E had spent his childhood. There were two sons, of whom E was the elder, a position that entailed the maximum exposure to the parents and their customs and beliefs. Like the figurehead on the bow of a boat, E had received first the impact of their natures, to which the momentum of youth imparted a continuous quality of violence. This violence was societal rather than personal, for his parents were people of strict conventionality and religion. Later he saw himself as a door between them and the whole notion of inner life, and his discovery that this door could be kept shut was both relieving and fateful. His younger brother used the existence of that door to free himself from certain inhibitions and constraints. Later he claimed to have been greatly marked by the parental regime, and it was in his ability to make this claim that the difference between him and E lay.

E left the town as soon as he could, going away to study and then working as a teacher. He had thought that he would find sympathy among children. His own childhood appeared to qualify him for that sphere, as though this were his expertise. His ambition, so long held that it had more the character of an assumption, was to be a writer, and it had seemed to him that teaching would naturally fit with that goal. But in fact there could have been nothing worse than to encumber himself with the obligation to form and control children. One day he simply abandoned his post, telling no one except his brother, and for many years afterward his parents continued to believe that he was a schoolteacher.

The brother lived in the city now, where he was distinguishing himself in academic and philosophical circles. E met his brother’s friends and associates, clever young men who played indefatigably with language, like athletes. Their sport was to take a precept that had functioned eternally as a pillar of reality and demolish it: reality did not generally, as a consequence, come tumbling down, but one’s sense of its solidity and familiarity was altered. Obtuse with innocence, blinkered by a lifetime of dissimulation before authority, E was slow to realize that many of these men—including his brother—were homosexual. The brother talked openly, even obsessively, about the privations of his childhood and the deformation of body and mind that was the result of having had to conceal his true nature. He wrote philosophical articles advocating for the sexual liberation of children and published them under his own name. E did not discuss these articles with his brother, and was generally silent in the company of his brother’s friends. He hid from their upending of conventionality much as he had always hidden from its enforcement. He had found an apartment of his own in the city. Alone for the first time in his life, he looked out the window day after day at the rooftops and sky and considered what he would do.

The view from our window is of rooftops and sky, and of other top-floor windows set at angles determined by the pattern of the streets below. The emptiness between the buildings is thus shaped according to the same pattern. This elevated world, with its streets of air, seems to suspend the humans who live up here in another element: the windows are a kind of lens through which they become representational. The building opposite has a little round window in its mansard roof, and sometimes the face of a small girl appears there. When she notices that she is being perceived she waves, as though from one boat to another. Often people open their windows and lean out, looking down and around. Being seen while seeing, they are doubly illuminated by the light of perception. At sunrise, across the void in the quiet of morning, a man appears on the balcony opposite to smoke, the lower half of his body wrapped in a towel. He is young and bronze-chested. He lights his cigarette and looks at his phone while the pink light fills all the windows behind him. His freedom in that moment seems absolute.

At night, when the lights are on, the scenes playing high up in the windows are framed by emptiness, like the paintings of Edward Hopper. They are paintings of people in rooms, together or alone, seen through windows or across spaces by an eye that seems larger and more omniscient than a human eye. It could be the eye of a god, or equally that of an animal or a child. Hopper was interested in the theater and in stage sets: another explanation for his lines of perception, so frequently bizarre, comes when one imagines that one is viewing these scenes from a seat in the stalls or the gallery. His human figures have a theatrical quality. In the recurrence of their own lives they seem to exist outside time. Some of that quality is present in the view from our window, not because the people are consciously enacting themselves, but because perception itself—the pure perception that involves no interaction, no subjectivity—reveals the pathos of identity.

Does it help us to be seen, even when we don’t know we are? A mother is continually seen by her children, whether or not she credits them with a point of view. From the beginning they are amassing images of her, of her body in all its angles and positions and moods. Her body becomes the known point from which they broach all that is unknown. They see her mainly when she is paying them no attention; when her attention comes it is seismic, as though an actor had suddenly turned and addressed a member of the audience. They see her when she thinks she is alone, despite the fact that they are there. These witnesses of her that have grown out of her can startle or displease her with the independence—the non-bias—of their observations. They are not extensions of her own will and consciousness, and in this way they inform her that she cannot control what is known about her and does not entirely know herself, that they know more about her than she does about them, since they have not yet become themselves. Yet her power to wound them is limitless.

She had had many pregnancies, and had become steadily debilitated by excess weight and sedentary habits. She seemed to want and welcome debility: perhaps it was a way of drawing attention to the site of contention that was her body. Her personality, so dominant, was clad in the statement of its own ultimate disempowerment. She offered her flesh as another person might offer their beauty. This flesh was a sort of outcome, the result of all the things that had been done to her body during her life, whether by herself or others. Inexorably, year by year, she lost her shape. Her formlessness became a sort of challenge to the notion of form itself and to conformity. She discovered that she could use this non-conformity to control what people expected her to do and therefore what they were able to do themselves. In this sense her formlessness was the active counterpart to her beauty. When she had possessed beauty, her management of outcomes had been far less successful. In formlessness she discovered power, and also the freedom from limitation.

She laid claim to all kinds of maladies, had unnecessary operations, and took all the drugs the doctors were willing to prescribe her; she insisted on using a wheelchair, and eventually refused to walk at all. When she said she had cancer no one believed her: it is possible she didn’t believe it herself. But finally, one day, a doctor confirmed it. He told her she would shortly die, and her response to this news at first was as to the fulfillment of a fantasy of attention or importance, as though she had at last been offered the starring role she had always felt was destined for her. The encounter with reality, deferred for so long, avoided by so many ruses and fictions, proved in the end hard to recognize. She mistook death for a compliment, and when finally she realized that this dark stranger was not a prince but an assassin, she struggled vainly to get away. She tried to walk: the news reached us that after all these years of half-voluntary paralysis she was attempting to get out of her wheelchair and walk. It seemed she thought that she could simply stop playing, stop pretending—that she could reverse her will and take refuge in reality. But for her there was no longer any reality: she had long since broken her contract with it. She had allowed it to decay all around her, in her pursuit of limitlessness.

Some weeks after she died she entered our dream, walking through it without seeming to see it or know she was there. She was giant and doll-like, an inflated, unclothed figure moving robotically forward as though in a trance. The people in the dream moved out of the way to let her pass. She saw nothing and nobody, walking mechanically past them and away, walking naked out of the dream as she had walked into it, as though her fate was to walk and walk in this monstrous fashion for eternity. When she passed us she showed no recognition. We looked at her face and felt a leap of consternation and pity. It was her true face, the one we had never seen but had somehow known about and imagined since childhood. It wore an expression of unspeakable unhappiness.

Alone in the city for days at a time, E worked on a novel. It concerned the lives of people in a bourgeois country town over the course of one summer, people paralyzed by the disconnection between their inner and outer lives and by the difficulty of locating authenticity in their own feelings. They lived in a comfortable household and spent their time on pleasant summer activities, but their glimpses of the moral and natural beauty of the world only made their attempts to relate to one another seem ugly and false. The coupling instinct, with its flirtations and ellipses and adherence to the narrative framework of romance, felt burdensome and constraining, like an artificial limb. Yet in fact it was this marriage of instinct and narrative that would eventually drive them into social conformity. The youthful truth of their feelings, along with their bonds to nature and spirituality, would be lost.

A publisher bought the novel, which came out under an assumed name. E had made up this name midway through his writing process, when it became clear to him that he was unable to write freely as himself. The prospect of being identified with his own actions plunged him into the same dilemma as that of his characters: the loss of an internal truth through the construction of external identity. There was shame and inhibition, too, at the idea of the people who knew him—his parents above all—having this open access to his private world. Even the thought of it was intolerable.

By contrast his brother seemed to relish his open confrontation with their childhood and its conservative perspectives. Why should families go unchallenged by the reality that comes to them through their children? The whole question of authority, and of the institutions that embodied it, was changing. He had been awarded a professorship at one of the city’s most illustrious universities. Who was to tell him what he could and couldn’t think? From this perspective E’s use of an alias was undeniably cowardly, but for E there was also a question of responsibility that his brother seemed content to ignore. To inflict, to cause, was also to entail responsibility. His fear of inflicting and causing almost amounted to an aesthetic and moral objection to the phenomenon of causation. Yet his use of an alias had the appearance of a criminal luxury, to the extent that it could have been said to be a form of cheating. To conceal identity is to take from the world, without paying the costs of self-declaration. When his novel failed to attract any attention, he wondered whether it was in punishment for this crime.

In the city he began to meet artists and writers and filmmakers, young people caught up in the dynamism of remaking culture for the modern era. Like his brother’s, their ambitions involved a radical confrontation with conformity, but in this case they were focused on redefining the relationship between art and reality. Some of them were already becoming famous, and he watched as their identities grew inextricably intertwined with their creations. When they brought out something new, it was compared to the last thing they had done; it was praised or criticized on that basis; a familiarity, a form of ownership had been established that permitted judgment. Why was it impossible to create without identity? Why did a work need to be identified with a person, when it was just as much the product of shared experience and history? Some of his friends became bolder and more arrogant with success. Their voices grew louder, their opinions and convictions began to entail a kind of deafness. Watching them, E felt a curious sense of isolation, as though he alone could see and hear. In being and defending themselves, they cloaked the world in their subjectivity. He began to understand that the discipline of concealment yielded a rare power of observation. The spy sees more clearly and objectively than others because he has freed himself from need: the needs of the self in its construction by and participation in experience.

Meanwhile E and a few others had set up a magazine, where E wrote about film under another assumed name. It was unlikely his parents would ever hear of these essays, but all the same he knew they would disapprove. His was the opposite of his brother’s attempt to heal the self by seeking the root causes of its unhappiness. It was, in a sense, an ultimate autonomy. Yet his disguise seemed to lie beyond the preserve either of love or freedom. Rather, there was something theatrical, something almost godlike about it. It was both humble and divine, this management of the power of disturbance, born no doubt of deep habits of deception or of the obligation to deceive. The humble god who avoids violence and is bent on the preservation of things as they are: this was the god he wished to recognize. In the service of that preservation, sovereign identity must be dethroned. Invisibility was his conduit to self-expression, though it had done nothing so far but consign his work to oblivion. Yet while he was invisible he was free.

The memory of his novel embarrassed him: his idea of writing had begun to falter. Of all the arts, it was the most resistant to dissociation from the self. A novel was a voice, and a voice had to belong to someone. In the shared economy of language, everything had to be explained; every statement, even the most simple, was a function of personality. He remembered how exposed he had felt as a child, as his mother steadily built a panorama of cause and effect around him. He was publicly identified with everything he did and said, as well as with what he did not do or say. Writing seemed a drastic enlargement of this predicament.

He completed a collection of stories, little morality tales for the modern era, or so he thought them. They concerned ordinary people in moments of intimate dilemma. They revealed—so he thought—all the simple beauty of the self, faced by the problem of truth. Instead of directing his characters he merely watched them, without interfering, like the humble kind of god. He watched them lovingly, for the good and the bad in them. He brought them no drama. He forced nothing on them, extended as they already were by the task of living. The things that happened to them and the choices they made could always, he found, be connected to them in a unique way, not by any external factor but by something much finer and more delicate, something more in the way of a compass inside each one of them. He was adept at sensing the minutest tremors of this compass. His publisher rejected the stories. What’s happened to you? the publisher said exasperatedly when E came to his office. You were modern when you started, and now you’ve gone back into the last century!

We resumed our lives after the funeral as though nothing had occurred. There was the feeling that something had stopped and something else had begun, but neither state had any clear definition. They were empty spaces with no content or language. There was the feeling that they ought to have been full with the knowledge of possession and loss. Sometimes we were arrested by the sensation that we were now alone in the world, but how could that be? If it were so, then we had always been alone.

She had liked us best when we were small children, before our will and character began to obstruct her will and character. Once she said that what she had in fact liked best was being pregnant. In pregnancy she had received attention for what was as yet a swelling mystery, one that also had the advantage of excusing her from the requirements and obligations of normality. This attractive prospect may have been what tempted her to repeat the exercise so often, even—or especially—when its pitfalls were before her eyes. But pregnancy is not a sustainable state: perhaps her discovery that she disliked reality and its logic was made there. Pregnancy was a kind of authorship in reverse, where the work started after publication and the suspension of disbelief came before the story had begun. She was creating, sure enough, but what a troublesome creation it turned out to be, leaving her no peace, disobeying her intentions and, most of all, proving impossible to put an end to. Pregnancy concluded with the drama of birth. Love ended with the spectacle of marriage. But we didn’t end, not even with our own marriages, the births of our own children.

She wanted us to be finished but we could never be finished. We kept existing and ruining the order of things. We got into trouble for existing in this way. Her anger was easily aroused by disobedience and contradiction. Nothing we did wrong could be forgotten, and so as we grew older we felt more and more uncomfortably weighted down by our characters, which seemed to have been imposed on us. Her ambitions for us were uncomfortable and didn’t seem to fit us. We were embarrassed by the story she had fashioned for us and the roles she had given us. We discovered that for the story to work, a great deal of license had to be taken with the truth. The strange feeling of liberation at her death was in fact our liberation from this story. But why had she created it?

Once we had become adolescents, and had started to query her version of our life, she did something unusual: she began to make up new stories about the time that predated our existence. It is the strategy of dictators, to rewrite history. Was this what she was? The stories concerned herself and her life before she met our father. It was easy enough to discount them by a simple calculation of dates, but this only seemed to increase their maddening power. In one of these stories there had been another suitor, before our father. Unlike our father, this suitor was rich, aristocratic, and charming, with connections to high society, and he had wanted ardently to marry her. His parents disapproved, and sent him away for a year to the colonies, from where he promised to write. But no letter came: for a whole year she waited, pining, for word from him. Then one day, looking in her sister’s room for a missing blouse—the sister was always taking her things—she found a shoebox of letters under the bed. All these months the sister had waited jealously for the postman and intercepted the letters, which had arrived diligently every week. In the last letter he declared himself to be giving up hope, not having had a reply from her in all this time.

Another story—or rather set of stories—concerned her employment as assistant to a certain Sir Edward, an homme du monde who traveled around the fashionable watering holes of Europe among a coterie of celebrated artists and intellectuals. The Sir Edward stories had the character of an inexhaustible series. She found that she could lay claim, through Sir Edward, to a whole range of people and places, and to having participated in some of the key cultural moments of the epoch. Mixing in these circles eventually led to the discovery that she herself possessed artistic talent, and with Sir Edward’s encouragement she enrolled at the Chelsea College of Arts. Later it became the Slade School of Fine Art, when she realized the Chelsea wasn’t as well regarded. She generally stopped short of claiming outright that our father had put an end to these romantic and artistic adventures. Just before she died, she told him that she hated him.

We lived in our bodies as in a constant state of emergency. We wore them out trying to satisfy them. We never succeeded in losing ourselves in sleep or pleasure. We were vigilant and wakeful. We always knew what time it was. We were forever trying to fill or close some gap, and it gradually became clear that she was the origin of it, of this unbreachable distance within ourselves; perhaps it was in fact the gap between her body and ours that tormented us. We exhausted ourselves trying to fill or close it. When we saw people who were free from this struggle it saddened us. It reminded us of something we knew we ought to have known.

We had considered neither language nor silence in relation to this gap. They were irrelevant to it, did not belong to it. In fact they belonged to her: she used them both as instruments of terror. The death of her body promised their liberation. It was strange to consider that while the gap in our bodies would remain unresolved, we might avail ourselves of language and silence. There had been no silence that was not an aggression, no language that was not an attempt to exert judgment and control. Silence had filled us with the panic of abandonment; language had seemed a kind of evil, capable of destabilizing reality. One day they might become innocent again. With her body gone, what would we say or not say?

For many years love remained a mystery to us, and in its place we practiced concealment. Everything that we cared about and desired had to be hidden. We did not know that outside in the world this element, love, encompassed all that was freely available to us. Instead, when it was offered we spurned it. Convinced that everything had a price, we lived in the terror of discovery. We were suspicious of those who lived in love, who gave and expected nothing in return. Sometimes we encountered the shocking faces of reality—suffering, injustice, pain, and loss—and wondered in our hearts how such things could possibly be borne. Our bankruptcy in love left us with no ability to bear them. Yet she—and we—were largely spared reckonings of this kind. Misfortune never knocked at her door, demanding payment. Catastrophe never came for her. She was never checked by reality, and this gave more power to her unreality. She disliked and was suspicious of the sufferings of others, which detracted attention from herself. She disliked the spirit of exploration. She disliked freedom, and bequeathed this dislike to us. She disliked all threats to her subjectivity. Most of all she scorned the truth, taunted and baited it and laughed in its face, and not until the very end, when death came and waited by her bed, did the truth act to defend itself.

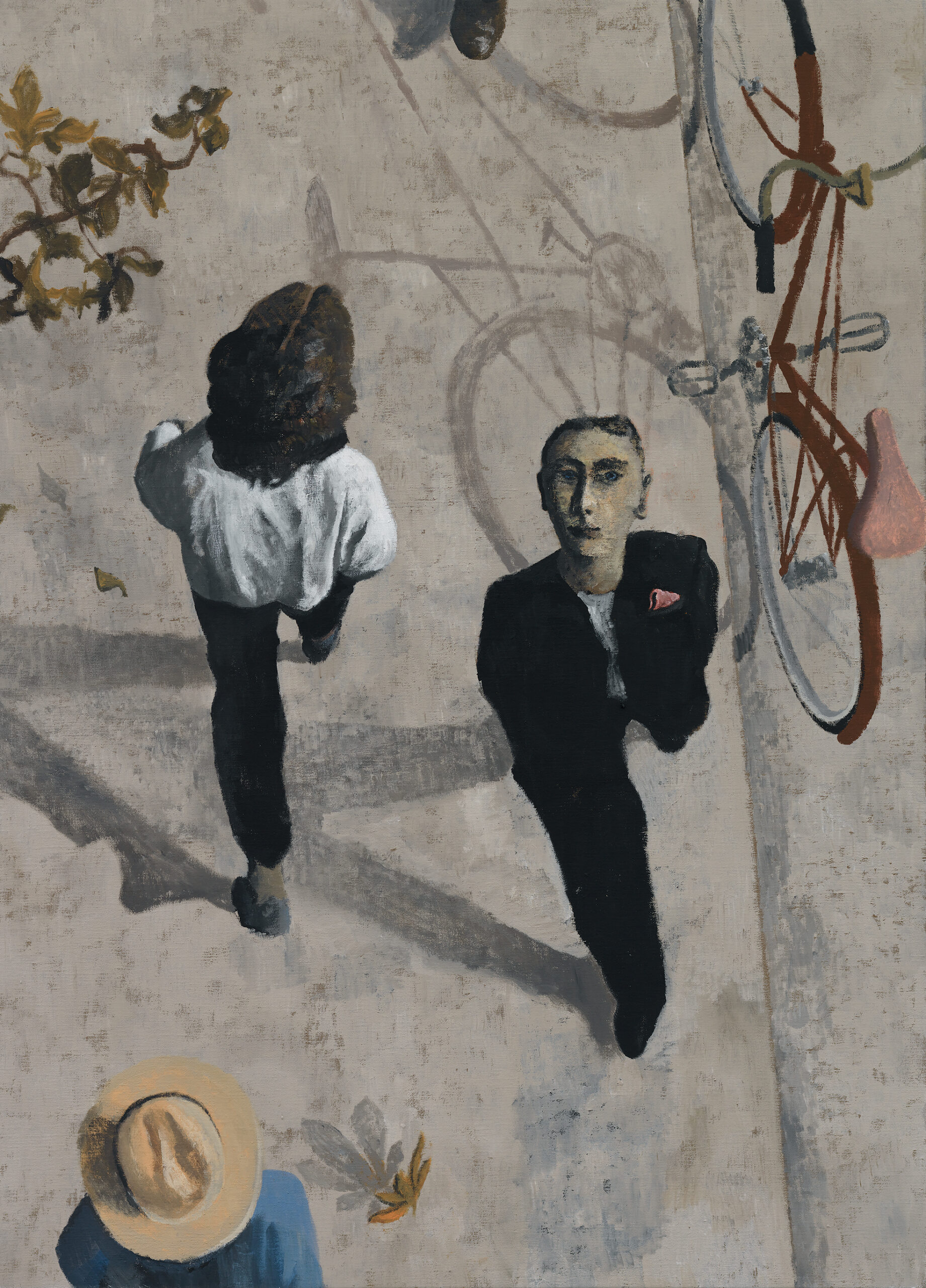

Man Looking at a Bird, by Lenz Geerk © The artist. Courtesy the artist and Roberts Projects, Los Angeles

Someone gave E an old film camera, and looking through the lens he recognized this as his home. Its unbodied mode of perception—even if it was to some extent an illusion—furnished him with a hiding place. When he was behind the camera, he believed he could not be seen.

His years of watching films and writing about them had given him a tetchy sort of autonomy. He knew what other directors had done and were doing, what they were likely to do. He was familiar with the brutal grandeur of the highest achievements, the epoch-making spectacles of genius in this new and violently meaningful form, which married personal vision with extraordinary public impact and power. He knew that it embodied change, and he wasn’t interested in change. He was interested in the fragments that change leaves behind in its storming passage toward the future.

His novel had been a failure but it had garnered him a quiet sort of authority, because the proponents of change—the brutal geniuses—are susceptible to the notion of a seer in their midst. These men of power were surprisingly attentive to what E had to say. They wanted his approval while completely ignoring his opinions, which were not the opinions of the majority. He posed no threat to them, with his austere and threadbare vision of life. But they recognized his connection to the truth.

His first attempt at making a film was a disaster. He was unprepared for the practical complexity of it, its tedium, its sprawling technical reality. He irritated the people whose help he needed, the crews and technicians of whose importance he had been arrogantly unconvinced. He was at once controlling and incompetent. The simplicity of writing, its humble mode of transferring vision, was immeasurably distant from this strange and cumbersome process of recording. It seemed to go against the force of gravity—all these people, all this equipment, all this expense that was required to get his vision airborne. It directly contravened his nature and his view of life. He failed to comprehend its organizational basis and its reliance on time and location. He failed to accept that there was no place for daydreaming, hazarding, grasping. The gleaming prospect of invisible authorship had been replaced by a monstrous task of practical management.

Yet he did not want simply to return to writing: he was forced to recognize that the last thing he wanted to do was to sit alone with himself in a room. It was what he had always imagined for himself, but still he was unable to do it—a double failure. What was he trying to capture? What ineluctable vision, a vision writing was so far from comprehending? The statement of writing was already too crass, too formulated for this vision. The writer writes about what he already knows and has decided is there. He pretends he doesn’t know, hasn’t decided. He sells this illusion to the reader, who joins him in the labor of fantasy. E’s vision was the opposite of this. He wanted to be innocent of knowledge. He wanted simply to record.

One day, for no tangible reason, he suddenly understood something: What he hated and resisted about filmmaking—its boring practicality—was the key to his vision. His religious upbringing had left him with some suspicious notions about suffering and divine intention. But the more he considered it, the more he realized that this was not the redemption that comes from doing what is hardest. No, it was by taking responsibility—something he had never done—that he would be redeemed. Other people were redeemed in this way by having children and the task of caring for them. Similarly this offered the prospect of an advance into the mechanics of reality, by comparison with which the notion of sitting alone in a room writing a book seemed entirely pallid. It was easy, as a writer, to hide behind a pseudonym. But to go out into the world anonymously and record reality was a matter of enormous difficulty.

It interested him that actors pretended that the camera, the audience, was not there. Perhaps people pretended God wasn’t there in much the same way. The sense of being seen was fundamental to the construction of civilized behavior, to the extent that most people continued to behave in that way even when they were alone. Why did they? If not the eye of God, was it simply the gaze of authority they felt upon them? He, on the other hand, had no feeling of being seen. On the contrary, he was surprised—horrified even—when people noticed or remarked on things about him. The gaze of authority had fallen on him so early that he had learned to put on a mask. But from the very beginning he had been aware of seeing as a type of power. To see without being seen: for E there was no better definition of the artist’s vocation.

He decided to do things his own way. He would assemble a cast of people—they didn’t need to be professional actors—and tell them what he had in mind. Sometimes he would leave it to them to decide what they were going to do and say. He would only use available light, which meant, he supposed, that most of it would have to be shot outside. If possible, he wouldn’t alter what he had shot. He considered the places where people gathered and were seen: the street, the park, the beach. He would use those places. The biggest problem, he supposed, would be the weather.

He found his thoughts returning to the stories he had written years earlier, the stories of young people in moments of dilemma and illumination. These stories, he realized, were the template for his vision. Just as they had seemed to come from life, so he felt certain he could re-create them as true experiences. It was no wonder the publisher had rejected them. They needed to be animated by all the tender unknowing and mystery of life itself. He didn’t want to direct them: he wanted to watch them happen.

The thrift and simplicity of E’s method made it possible for him to create not just one film but a whole series. No single one of them distinguished itself or created noise. They flowed quietly out into the world and seemed naturally to join the stream of life. In each one, a situation developed that had no clear beginning or end. It emerged and flowered and receded again over a day or handful of days. He was old enough now to know that these situations, these flowerings, which in youth seem almost incidental to the forward-driving story of life, in fact turn out to be life itself. It was in these moments of hope and expectation and disillusion, of prelude, before the will decides to conscript the self into conformity, that we had really lived.

It was noted that E’s films usually concerned the attempt by a young woman to remain free and truthful in the face of the deception and possessiveness of men. It astonished him to watch, over and over, the way his actors quite naturally found the language—the moral terms—for this struggle. The young women knew in their hearts that the freedom they wanted was not, in the end, available to them. And in fact the men who did understand their need to be free were not the men they desired.

With these little homespun tragedies E began to make his mark. But even when success came he kept to his methods and to his secrecy. No one knew anything about his life, his real name, his marriage and children, his connection to his notorious brother. No one knew what he wanted or why he was motivated to work in the way that he did. All they knew was what he saw.

We realized that we had relied from the beginning on the manufacture of desire-states to camouflage the problems of truth and limitation. Was there anything we remembered from the time before this reliance? Only fragments. Our mouths and bodies craved sensation. There was a terrible tension in the distance between our needs and their satisfaction. Later we made the discovery that we could create needs that we ourselves could satisfy. Later still we found that our will could enlarge the possibilities of this cycle, whose end result was never the transformation of our circumstances but the rendering of them more tolerable. Slowly we understood that need had a crippling effect: it made us inflexible and secretive. Our continual setting of goals and systems of self-reward separated us from other people. Yet other people seemed to possess some knowledge that we ourselves lacked. Our bodies felt unacceptable and cumbersome to us, as though they were a burden we would have to carry forever. Sometimes it felt as though only with the removal of this burden would we be free. There appeared to be some primary necessity we lacked and were therefore always in pursuit of. If this were so, its substance remained a mystery. We were tormented by something no one else could see. Yet far from causing us to flee, this torment seemed to fix us where we stood.

When it came to love, we found ourselves confronting a foreign language. We did not know how to estimate or value things that were free. The things that were free—sex, conversation, the smell of grass in summer—unsettled us. We sought to commodify them and create outcomes from them. But they seemed to belong to everybody: we couldn’t keep them for ourselves. So when the personal offer of love came, a specific love for us alone, it was irresistible. To the question Is this what you want? there was only one answer: Yes. To be given something for free was unparalleled in our experience. How could we refuse it? In the system of love, we soon came to understand, all the things that were free retained their appearance of freedom while in fact being conscripted into ownership. Was love itself a system of ownership? Often we received the confusing impression that love disliked freedom and at the same time sought to impersonate it. But in this foreign language we could never be sure.

Using the system of love we built a structure of possession. Our feelings lived in this structure and sought to replicate themselves there. They sought familiarity and the feeling of things being real. They sought repetition. Some of these feelings were presentable enough to show in public; others were left to roam the attics and cellars. We had the sense of our lives as a story: this had been the case for some time. According to this story the past was a place of un-enlightenment from which we were continually in the process of delivering ourselves into the future. Our habits of need and satisfaction had given us an interest in the future. The future enlarged the prospects of satisfaction and embroidered the sense of desire. We had visions of it that we described in words. We were continually creating it, making our way to it, yet we never arrived there. Often the present moment—the bridge to the future—weakened and collapsed while we were occupying it. Then we had to start building again. This interest in the future strongly resembled belief. The people who lived around us and perhaps loved us were struck by the strength of our belief. They listened to our visions of the future and sometimes participated in them. But they tired more quickly than we did of the effort it took to get there. They were more interested than us in the past and yearned for it. The present moment did not collapse under them: it was strengthened by this element—love—that we did not entirely understand. We tried to be loving but when the sound of footfalls from the attics and cellars was loud in our ears we grew impatient with love. We wanted to move forward, into the future.

We acquired things and used them and disposed of them. What we liked best was disposing of them. It felt like disposing of the bad and burdensome parts of ourselves. It felt, momentarily, like disposing of our own bodies. Sometimes we sensed that we were living counter to nature, were at odds with it, and this manifested itself as an intolerable feeling of material chaos and disorder, to which a material solution could usually be found. We felt both exposed by and imprisoned in what we had built and the story we had created. We wondered, very occasionally, who we were. We looked at our mother and felt, dimly, that we were nothing but a response to her character. When we saw her, the relief afterward of getting away from her was dizzying: in those first moments the possibilities of freedom rose before us, as though all along there had been something we had, some alternative to ourselves, that we had failed to notice. But after a while a cold feeling of neglect would begin to grow in us. Without her scrutiny our lives felt unreal.

When we had children of our own, an era dawned that at first seemed to be characterized by results. Our children—the result of us—were not what we expected. From the beginning they seemed to know more than us. They seemed to contain some miracle, the spark of life, that we had never perceived in ourselves. We took their side—against what we weren’t quite sure—without question. We were proud of our results. We did not need to dispose of them. We did not need them to end. We lost some of our interest in the future: a day became the sum total of its parts. In fact, our children seemed already to contain the future, and as our knowledge of them grew, it became clear that it was knowledge of what already existed. How was our mother going to respond to these new allegiances? We believed that she too would learn from our children and profit from their miraculous wisdom. But when we offered our children to our mother, we were surprised by the judgments she made of them. She preferred one of them to another; she saw flaws in them, and compared their relative merits. She was not, as we were, transformed by them: in fact she made the suggestion that our management of them was inadequate, that we were ruining them, and with this, her first major tactical error, her power over us was suddenly broken.

Our children taught us how to love, and slowly we began to understand the extent of what we ourselves had not received. We began, for the first time, to love one another. We loved one another with the simple love of children, which had returned to us from the time before the beginning, the time we couldn’t remember, the time before our reliance on satisfaction and need. Our mother tried to disrupt the new bonds of love that were growing among us, but we found that this simple love could resolve the misunderstandings that arose from her interference. We began to talk about the past, and discovered that our accounts of it were all different yet in some sense the same. Slowly, falteringly, a picture emerged. Sensing rebellion, our mother resorted to harsher tactics. Some of us were more susceptible to her control, others less so. On the latter she simply turned her back. For the first time we recognized ourselves as fit to judge her, for now we understood what it would be, to turn your back on your child. We knew that we would be incapable of turning our backs on our children. For the first time, an incapacity had the weight of riches.

E returned home to the bedside of his mother, who was seriously ill. He had been busy with work and it had been longer than usual since he had visited. Thus it seemed to be his fault, the desiccated body on the bed, as white and light as the brittle seed casings that whirled down from the sycamore tree outside the window. Only her breathing, noisy and labored, distinguished her. His father was behaving erratically. He stood at the foot of the bed and, raising his voice in command, ordered her to get up and make lunch. She didn’t hear him, didn’t get up. The father was unable to look after another human being. He was unable to communicate in any way other than by giving orders.

E went into the town by bicycle to get medicine. The town was more or less the same as it was in his youth, except that now it was full of cars. E hated cars with a passionate hatred. He refused to get in them, even taxis. It wasn’t just their ugliness and the filth they spilled that repelled him: they were humanity’s decisive step in its move away from nature. He credited them with the power to destroy self-control, sensuality, intimacy itself. He also saw that with this development his own future as a chronicler had been threatened. He would be left behind, by people in cars. His characters, spiritual and actual pedestrians, would be drowned out in the noise and dust.

He sat by his mother’s bedside and stroked her bony forehead and her thin, silken white hair. Her eyes were closed. He could look at her for as long as he liked: for the first time in his life, there was nothing to stop him. He wandered around and around her face as though it were some official building that had finally been opened to the public. In their way she and his father had been a form of government: they presented themselves to their children as part of a greater authority whose machinations were impersonal. He wondered what their true feelings were and whether they had ever had access to a sense of self in their serving of these ideals and regulations. It surprised him when his father said, over the lunch E had to make for him, that he blamed E’s brother for the mother’s perilous state. Not long ago the brother had published a barely veiled account of their childhood. It too viewed the parents as a regime, a far crueller and more culpable one than in E’s vision, one that actually set out to crush and incapacitate the individuals under their care. The brother’s obsession with what the world saw as his abnormal sexuality—his profound lack of self-acceptance—led him to retaliate with the full force of accusation and blame. It was evident the parents had read this book: the brother had published it under his own name, after all. The mother had been proud of the brother’s achievements, the father says now, but it would not have occurred to her to see herself as connected to them. It is the shock that is killing her. What kind of grown man walks around blaming his mother?

E does not tell the father that the brother regularly appears at debates and even on television, calumniating the parents and arguing for the sexual freedom of children. He is part of a cohort of intellectuals who hold the belief that the pleasure of the body is sovereign and should be liberated from all convention. It seems the childhood freedom they are arguing for is in fact the freedom for adults to have sexual congress with children. People are disgusted and shocked by this notion, but E’s brother doesn’t spend his time with such people. E does not involve himself in these arguments. For him, an adult is merely a corrupted child, who has availed himself of the weapons—and then the crutches—with which society is only too happy to supply him. It is all he sees, the child inside the adult’s body, crippled and corrupted by money, fear, gluttony, conformity, addiction: he even sees the child inside his mother, lying dying on the bed. How, he wonders, did we become so evil? He sees that it is possible to live the span of a whole life and never once realize that the truth of oneself has been destroyed—not only possible but usual. In his films he delicately, obsessively tracks this relentless loss of innocence, a loss that occurs in moments of barely perceptible action and interaction. At the center of his dramas there is very often a person who proves harder to corrupt, whose innocence is more shining and resilient than that of others. The sufferings and progress of this person are his true subject. He is in no doubt that his anonymity is what allows him to see what he sees. Because of it he has no investment in the game of life. He is a spy; his ego is exiled, at bay. Like the spy, the difficulty is that he can’t make things happen—he just has to be sure he’s there when they do.

This idea that E’s brother has killed their mother has taken hold in the father so quickly that he is soon treating it as a matter of objective fact. The father himself takes no responsibility. The sight of the mother’s withered, wordless body, her withdrawal from the field of action, is so unacceptable that someone must be to blame for it, and he has been trained to blame anyone and anything other than himself. Presently he asks about E’s supposed teaching job and his life in the provincial town where he believes E still lives. He has never shown any interest in these subjects before: all his ambition was invested in E’s brother. Now he is writhing like someone who has backed the wrong horse in a race. It is with the greatest effort that E tolerates his father. Were it not for his mother, he isn’t sure he would have taken the trouble to disguise his true identity. The thought occurs to him that perhaps he wouldn’t have had to: perhaps she would have accepted him, protected him even, if she had been left alone to care for him naturally. Instead her own oppression became his, the cruelty she had been offered became the cruelty she passed on. He detests men, detests all that they are. His belief is that women are the true creators: they are motivated to give, and in the generosity of their creativity they inadvertently make themselves slaves and henchmen. The creativity of men, which is not creativity at all but a mode of conquest, disgusts him.

The doctor comes. The mother is not going to recover. She will not be getting out of bed and resuming her activities. She has gone somewhere, to a kind of middle land between life and death, from which she cannot come back. There is no knowing how long she will spend there. E makes phone calls and rearranges his plans. He sits by the bed and waits while the light travels from one end of the room to the other.

Many of the objects around our mother’s deathbed had existed for as long as we could remember. When we first entered her room we saw and recognized them more clearly than we recognized her. These objects contained our mother. They were more reliable and lasting than she was. It seemed impossible that she would die because she had never told the truth, but the objects told a different kind of truth. Their actual existence and their existence in memory were the same. She had imagined she was stronger than them, that she had owned them, but in this element of consistency lay their victory over her. It was they that would commemorate her.

We were together again in our parents’ house, as we had been in childhood, except that now our bodies were the used bodies of adults. We were frightened. We were frightened but we lacked the darting speed and lightness of children. We lacked the ability to conceal ourselves. We moved around uneasily with our garish voices and our creased, reddened faces, and the passage of time seemed terrible and incomprehensible to us in the light of our fear. The prospect of our abandonment had never left us, and yet its realization now had caught us somehow unawares. We gathered in doorways or corridors or the corners of rooms and dispersed again. We did not sit down. The door to the bedroom was frightening. We were still the children of the figure lying on the other side of it. Our fear of her and our fear of her death were difficult to distinguish from one another.

In the bedroom she lay in her nightdress as though on a plinth. She appeared to be being sacrificed. Was it we who had demanded it? Was it our fault, our wish that she would die? Her face was a mask of bone offered to the ceiling. The thin matted hair lay around it on the pillow. We felt that we did not know her, that she was unknowable. We felt that we ought to save her. But we were children: we didn’t have the power to save. Were we to worry about her? But who would worry about us, when she was gone? We remembered a day, when we were small, when she had been very unhappy. Our father had been at work. She had lain on her bed in her nightdress and cried, and we had gathered around her trying to comfort her. We remembered the pure sorrow and pity we had felt. Now we were gathered again around her bed and what struck us was the loss of this purity. It had been squandered, or she had squandered it. We remembered what it was, to have felt so purely.

Our father’s behavior was disordered and occasionally violent. His reality was being upended: he was being turned upside down. He had the appearance of a malfunctioning machine. He stood at the foot of our mother’s bed and shouted at her. He was angry with the nurses, who came and went in their cars. He talked about the food he wanted and wasn’t getting. He wandered around the house at night, turning on the lights, turning on the television at full volume. It was evident that he continued to share the bed on which our mother lay. In the daytime he did not, as we did, sit at her bedside. Each time we came out of her room he asked us whether she was dead yet. He did not appear to want to save her. He was like an animal that had been flushed out of its cover: with her retreat he was steadily being exposed. Like her, he momentarily mistook death for freedom. He talked about the things he would do when she was gone, things she had prevented him from doing. But it was too late for him to do these things.

Her breathing was slow and noisy. Sometimes there were long interludes between the breaths and we wondered if she had died. Then she breathed again and the matter of death seemed consequently to have grown more complex and opaque. We did not know what death was. We did not know how to die. If not a natural cessation, what was it? What qualification or readiness was lacking here? The longer we sat and listened to her mechanical and aimless breaths, the more apparent the absence of nature became to us. Nature was not attending her deathbed, was not in this room nor anywhere near, had not been seen or asked after for many years. In fact we had no memory of nature at all, and this, we began to suspect, was why we had no knowledge of death. There had been nothing natural in our dealings with our mother. We had been taught to suppress nature. We had been taught to regard the natural processes of our own bodies as disgusting. How were we expected to conjure death? Sometimes she would open her eyes and the glimmer of consciousness became visible. We had heard that in recognizing death people recognized a greater mystery, the mystery of life. We had heard that these could be moments of revelation. But in her eyes there was no suggestion of revelation. What we saw in her eyes were the vestiges of her control of the story of her life. The difficulty lay in the extinguishing of the storyteller. How could she tell the story of her own death?

We thought that love might help her out of this difficulty. We thought love might show her how to die. Sitting by her bedside we tried to offer love as we might have tried to communicate in a foreign language, clumsily but out of necessity. Ridiculous as we felt, we tried to be sincere. It struck us how naturally we spoke in our own language of love: in our love for our children, for instance, there was none of this clumsiness and constraint. Why did we love our children? How, when we had not inherited the language of love, had we learned to speak it? Perhaps, after all, we spoke it badly and ridiculously. It seemed all at once terrible to be us, terrible to be without origins in love, without language. Slowly we stopped trying to offer love to our mother. We stopped our awkward caresses and our unnatural words. We fell silent as the mechanical sound of her breathing came and went.

The nurses had said that she would shortly die, but the days passed and she did not die. The problem, it seemed, was after all a problem not of nature nor of love but of truth. The truth was that they had stopped giving her nourishment. They had stopped giving her liquid. If it was unclear why her body should die by itself, this lack of sustenance gradually took on an inevitability of its own. She appeared to be dying of death, dying because it had been decided that she had to, dying because in the absence of love or nature there was no reason for her to remain alive. No one suggested that she should be given nourishment or liquid. No one suggested that she should endeavor to remain human and alert in the encounter with death. In fact death wasn’t coming, and with the failure of death to arrive, a substitute seemed to be presenting itself: disposal.

We went away, back to our own lives. We left her with the agents of disposal, the nurses, our disordered father. We were told that one night, getting into bed, he noticed that she had died and had gotten in beside her and gone to sleep. At the news of her death we felt nothing, and understood that to have felt nothing was the greatest tragedy that could have befallen us, for its effect on us could only be to reveal greater depths and breadths of non-feeling, such that it almost seemed to cancel us out. Since her whole life had been a fabrication, or a construction, we ourselves lacked a basis in reality. She had lied to us, even if only by not telling the truth or by allowing us to be lied to through her; had we lied back to her, had we never let her see us or know us, we might have saved ourselves. Instead we had exposed ourselves and our needs. We had exposed our need for nature and love and truth, and our blind belief in her as their representative. We had hoped that one day she would be revealed to be their representative. Dimly we understood that she was no more than the product of the things that had happened to and formed her, but the operation of her self, her soul, remained for us a tantalizing possibility. One day, we believed, she would step out of the artefact of her body and we would see her soul.

After the funeral we resumed our usual activities. When we happened to mention to people that our mother had died, their sympathy and concern were disturbing. It was on these occasions that we felt grief, or something that resembled grief. It was like the brutal turning of a rusty blade inside us. What we were grieving was the fact that nothing had changed or been resolved, and that we no longer had the chance to resolve it. We were full of a dark knowledge that had briefly surfaced and over which the waters of time were closing again.

We had obligations and responsibilities of our own. We traveled for work to foreign cities. In The Hague, in our free time, we went to the museum. It was late in the day, half an hour before closing, and we decided to see the temporary exhibition of works by the painter V. We were surprised that we knew nothing about V but in fact there was nothing to know: he was virtually anonymous. For centuries his work had been mistaken for Vermeer’s, and once the misappropriation had been realized his activities lay too far back in time to be reconstructed. There were only the paintings themselves in which to look for clues. The paintings were Dutch interiors and streetscapes. They possessed a great eeriness that was partly the result of their manufacture by an unknown hand and partly that of the strangeness of what they saw. They were often scenes in which apparently nothing was happening and where the basic formality of the captured moment was absent. In one, for instance, a middle-aged woman was sitting alone in an empty room reading a book. The room was full of a bare light but the windows behind her were dark: it was nighttime. She was fleshy, well-dressed, self-absorbed. This woman was alone in a way that was nearly impossible to represent—it might have been captured, for instance, on a security camera. Immersed in being herself, she was indifferent to how she was seen. This indifference was oddly familiar to us. How had someone observed her in that way, alone?

It was only after several moments that we noticed a face at the windows behind her. It was the face of a small child standing outside in the darkness. He was looking in at her, but she didn’t know he was there. She didn’t care enough to know: he didn’t matter to her. Yet he wanted something, was waiting out there in the dark for something. He wanted her to turn around and see him. In another painting of a similar room, again at night, there was a different woman sitting in a chair. She was leaning toward the dark window so that we could only see her back. She had half turned the chair around and was tilted so far forward that its rear legs had left the ground. On the other side of the window, there was again the face of a little child alone in the darkness. The woman was waving at the child through the glass, her hand and face pressed close to it, the chair nearly toppling with her enthusiasm. The child was smiling. The exhibition text told us that this was the only example in Dutch painting of a woman tipped forward in her chair to look through a window. But we had already recognized the rarity of love.

The next morning, in the hotel room, we stood at the window looking out at the curious devastation of dawn, its relentless casting of new light on old failures. We understood that the opportunity to disguise and transform ourselves had passed. We realized that the death of our mother’s body meant that we now contained her, since she no longer had a container of her own. She was inside us, as once we had been inside her. The pane of glass between herself and us, between the dark of outside and the day of inside, had been broken. We recognized the ugliness of change; we embraced it, the litter-filled world where truth now lay. This gray reality, this meeting of darkness and light across shards of broken glass, was our beginning.