All photographs of Cherry Road Learning Centre in Bonnyrigg, Scotland, by Alicia Bruce, October 2023, for Harper’s Magazine

© The artist

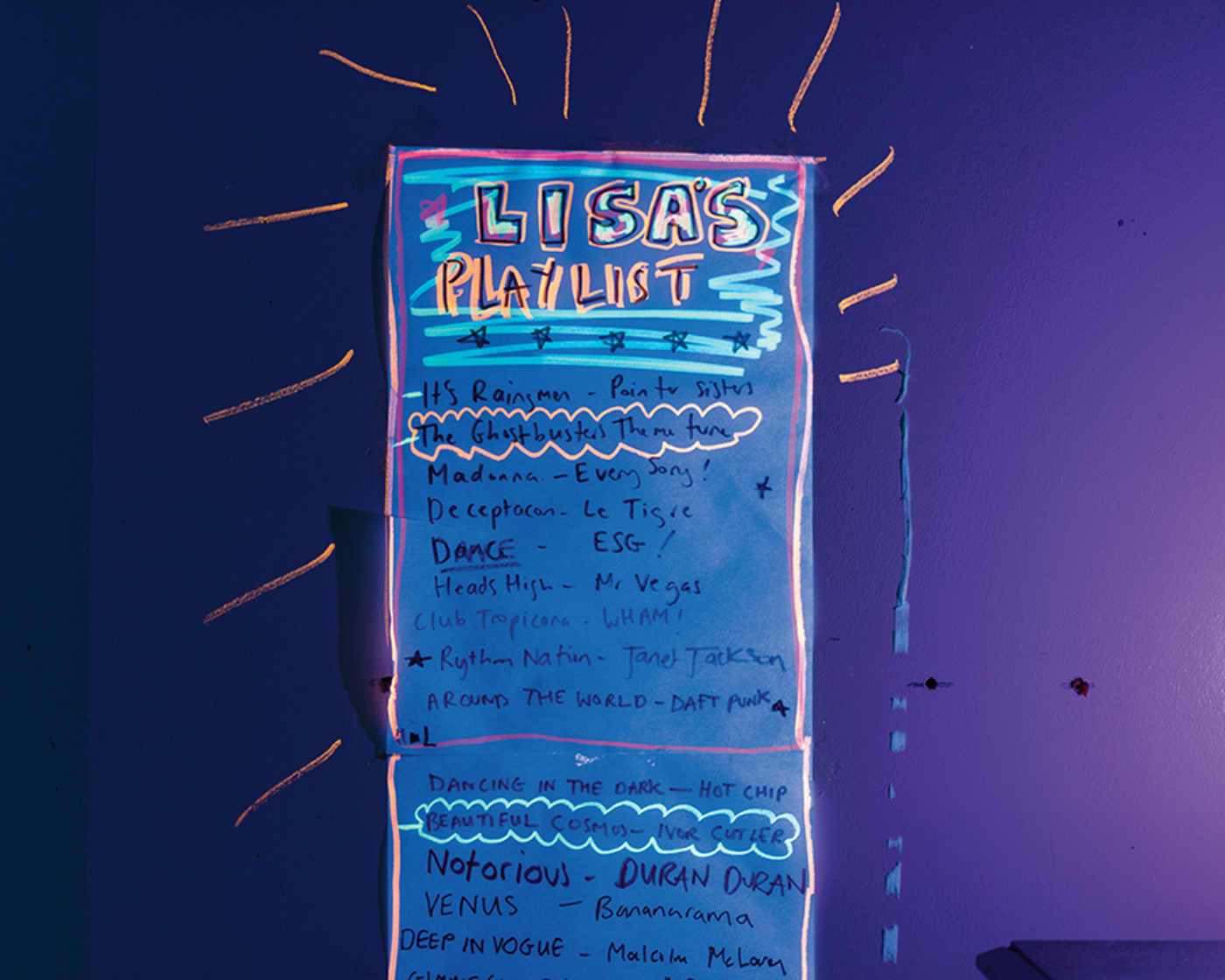

“Why not try chaos?” asked the artist Lauren Gault, her arms full of boxes and fabric, as she led me to a simple white cube of a room. The room was tucked into the back of the Cherry Road Learning Centre, a sunny building in Bonnyrigg, near Edinburgh. Lauren and Hailey Beavis, a musician, were a little breathless and pink-faced, busy readying stage materials, many of them strung up on wires that sliced the room—enormous lengths of black-and-white silk, oversize balloons, leis and beads, gold plastic fringe. At the room’s perimeter were a document camera, lava lamp projectors, beanbag chairs, microphones, and elaborate costumes, a stockpile at the ready before they began. Before they began—how to describe it? They raided a nearby closet for other possible materials, pulling out a giant mirror and some cups. Then Lauren switched on a fog machine while Hailey turned off the overhead lights and dialed up the big ambient bass. The room filled with the effect of dry ice. I asked her who she had in mind. “We have a couple of singing divas,” she said. “A magician. A Kate Bush fan.”

Starting on the hour, she and Hailey would host an array of visitors, some alone, some in groups of two or three, for around sixty minutes of—well, the professionalized term would be “art therapy,” but what was about to play out was much more like an avant-garde media performance than something clinical or teacherly. The room became a shadowy, immersive pool of sensation, a theater of enigmatic sights and sounds, none of it meant to be pleasant or pacifying. Lauren and Hailey would offer objects and experiences tailored to each visitor, some of which would be rejected, others enjoyed. It’s formally known as a “sensory workshop.” Every minute is realized in a series of exchanges signaling interest, pleasure, or discovery, very few of them with words: tactile sensation, physical comedy, drama, visual surprise. It might be thrash metal at top volume, or trippy neon bubbles projected across the walls and ceiling, or participants solemnly donning feather boas and stacking three hats on someone’s head: mutual curiosities would be established. A woman I’ll call Elizabeth* would be their first guest, arriving any second to put on a magic show.

Cherry Road is a day center—and there are thousands like it all over the world—a multipurpose civic architecture for adults with profound intellectual disabilities. In September 2022, I visited for a week to experience the sensory workshop, a long-running program unlike any I’d ever seen. The adults at Cherry Road may greet and smile; they may instead grunt or drool or stare, maybe whoop or shriek or belch, or some combination. Their habits and preferences may be immediately apparent or take months to discern. They include Nicola, a longtime attendee who sits every time in the same corner; she stays for hours in her favorite spot, saying almost nothing, and—insomuch as caregivers around her can tell—enjoying the sounds of things like a soda can dropping from a vending machine, a tea kettle’s raucous boil, or shoes in a washing machine. There are the twentysomething twins Simon and George, who rock in chairs and slap along to music. There’s Adam, a soccer enthusiast, who greets nearly everyone who comes in, and Christine, who enjoys group games and the garden. Some come by bus or by taxi. Others are dropped off by family. Their needs for assistance are intellectual but also often physical, such as help with daily activities like eating. They range in age from their early twenties to their sixties.

Presenting them like this has its hazards—sketching people who for much of history have been flatly rendered as patients at best, social menaces at worst. If I describe these scenes in the soft-focus, hazy language of specialness, the register is sentimental. If I avoid all human description, I obscure the vivid specificity of the individuals there—individuals whose names are mostly changed, whose interests are amended here and there to avoid identification. But the alternative is worse: perpetual invisibility.

By the time I got to Cherry Road, I’d spent a decade researching assistive technology and design for disability. Much of my work as a professor at an engineering school included examining the tools and technologies for bridging the gap between the atypical body and the built world. I had seen iPads unlocked using mouth sticks for people with advanced ALS, hearing aids that look like jewelry, neural interface technology for next-generation prosthetic limbs. These artifacts are made to support independent life, to assist people as they physically navigate public spaces or home environments, to help create flexible and accommodating workplaces. But no technology can make a just-right prosthesis for those with significant intellectual disabilities. The social and cognitive needs in that population largely defy clever fixes, not because their conditions are worse on some evaluative scale, but because intellectual disability is so diagnostically distributed and empirically variable. For sensory and mobility issues, I had seen plenty of innovation; I’d also seen some overzealous engineering blunders. But people with substantial intellectual and cognitive differences pose a distinct set of challenges. The sensory workshop makes common cause among people whose lively interior worlds need artifacts to connect, when connection is its own chief good. Encounters there are built on interests, and interests turn out to be the whole project: a starting point for understanding personhood far outside normative intelligence.

For a long time, Elizabeth wasn’t interested in the sensory workshop. She flatly refused to attend. Lauren, who has worked at Cherry Road for eight years, kept up the invitations anyway—just a friendly chat, might she like to come by? She eventually agreed to try it out for five minutes. And five minutes, over months, became ten, and longer, and eventually reached an hour. Today she arrived ready, using no words but walking energetically into the room, smiling mildly, straight hair half-up, half-down, except for a front section shorn close to her forehead. She paced the room with a rhythmic, punchy walk, pushing her head forward and grabbing the air with her forearms, her elbows extended from her sides. She pulled the world toward her as she moved through space, a strong metrical gait with all limbs engaged.

The artists were ready with the cups for a shell game, a cape, a wand, and some other potential props standing by. The smoke machine was perfect here—and with the lights low, colored projections, plus an intermittent applause track, they had the makings of a show. Elizabeth put the cape on and twirled as she paced. Hailey held up a heavy round mirror, three feet in diameter, to amplify the performance vibe. Elizabeth turned and preened.

Elizabeth also had an interest in circus-style strongmen that came from the Great Garibaldi, a slapstick character whom she had spotted in a television show. She had long been content to simply watch the show over and over again. Many people with a similar cognitive profile are left with just that as their primary activity: watching. Hailey and Lauren take these interests and turn them into real-life theaterscapes, with short scenes unfolding between the three of them. An actor who works in immersive theater once told me that involving audience members is a delicate art. You have to orchestrate a series of invitations, he said, usually just with body language. The bids for participating have to be appealing and simple at the same time. Invitation, variation, iteration: What might she enjoy? The same principle animates Elizabeth’s hour, with the artists hustling to change the scene every thirty seconds or so and make the proposals feel natural. Lauren and Hailey wordlessly hand off duties, one introducing a new scenario for the magic show, and the other altering the sound or lights.

“So much of life is happening at these people,” a Cherry Road team leader, John Connell, told me between sessions. “Someone else is deciding when they get up, when they have breakfast, when the bus arrives, what happens next.” There are lots of disability programs orchestrating shared experiences, he said. “But on whose terms?” It’s true. The crafts that proceed from intellectual disability often try to make audiences feel good; the handmade soap and beeswax candles are evidence that pleasurable and dignified expression can come from anyone. Rarely is it considered a multidirectional exchange, and still less a means for making art. The sensory workshop is something outside of enrichment, something much more unpredictable, a multipurpose room that can shift its shape a thousand times under the sustained improvisation of the people at hand. It’s an effort meant to loosen the day’s clock a little, let an emergent world arise for a short period of time, a source of discovery for both artist and guest. Hailey, who also works in care facilities for dementia patients, calls it “risky disco.”

That same day, I also watched Lauren and Hailey host Philip, who wore a tube attachment underneath his nose to help him breathe and was wheeled into the room in a chair. He sat reclining, splayed his arms, hands, and fingers wide in very slow movements. They were still getting to know him—“We think he’s a maximalist,” Lauren said. He is the Kate Bush fan, and he reserved his biggest face-cracking smiles for thunderous fart sounds played via mobile phone. Then there was Leah, who came in, kept her two coats and big headphones on, sang along to one Pat Benatar hit at concert volume, and left. There was Geoffrey, slight and dark-haired, who sat hunched in his wheelchair and rubbed his two pointer fingers on his lower temples. Earlier I had seen him laughing in a group circle. The artists rigged up big sheets of crinkly foil, set the lights into multicolor motion, offered him a flashlight and a swipe at the enormous, free-floating balloons, music tracks soft and loud. His face remained closed and unreadable to me, but Lauren and Hailey were trained on his micromovements; he would have been looking repeatedly at the door, they told me, if he didn’t want to be there.

And of course there was Elizabeth. “The amazing, the astounding, the heavyweight champion, Elizabeeeeetthh.” Lauren played announcer with a microphone while Elizabeth, silent, easily lifted an inflated plastic barbell, another feat of strength from the Garibaldi repertoire. Hailey affected difficulty with a matching barbell, stumbling under its burden, dramatizing her defeat over and over while Elizabeth gloried in the ease of her carry, her face illuminated, while she walked back and forth triumphantly, holding the weightless structure high above her head. The applause track roared and lights flashed, the smoke fading to the floor.

What are all the words for intelligence? Any serious consideration of intellectual disability begs us to defamiliarize the norm. The language for desirable neurotypicality is everywhere: bright, perceptive, quick, capable of abstract reasoning, all the words for braininess casually dropped by parents in playgroups. The people who attend Cherry Road are referred to as “service users”—a term no one particularly likes. They are sometimes spoken about in terms too broad or euphemistic to be meaningful: people with developmental or cognitive “challenges,” or the tepid and passive “differently abled.”

The old diagnostic words have mostly hung around as slang: idiot, imbecile, moron. But they were a way of carefully calculating the relative capacity for self-supported employment, as measured against the economic demands of industrializing towns and cities. As the historian James W. Trent writes in Inventing the Feeble Mind: A History of Intellectual Disability in the United States, the American understanding of intellectual disability shifted over the mid-nineteenth and early twentieth centuries to represent changes in the definition of personhood relative to work. As one late-nineteenth-century American institutional superintendent wrote, the feeble-minded were “not conducive to the national prosperity.”

Industrializing economies brought families into factories; asylums arose alongside them, forming warehouses for people with greater needs. Trent tells us that the initial purpose of these institutions was to train and then return people to their home communities, rehabilitated and therefore fit for community life. In need of justifying their existence, institutions recommended longer and longer stays, some amounting to a lifetime. Care, Trent writes, too often morphed into control. Orphanages, asylums, and workhouses established a new form of life for people ill-adapted to the public sphere, or even the private sphere of the parentless home. Or indeed the social contract.

I stifle a shudder some mornings when my husband and I watch our son Graham—at seventeen, the eldest of our three children, the one making hilarious asides at dinner, the one acting out plenty of ordinary teenage stubbornness, the one with Down syndrome—leave for high school. Not so long ago, kids like Graham were sent away, or segregated their whole lives, or hidden in homes, or euthanized. The idea that a person is no more than a wage earner is easy to criticize in the abstract, hard to circumvent in the particular, even now. The most baldly dehumanizing language has disappeared, but “high functioning” remains the bar. “Our contemporary phrases appear more benign,” Trent writes, but “too often we use them to hide from the offense in ways that the old terms did not permit.”

At lunch around a small, round table with Lauren and Hailey later that week, I heard about their work while Cherry Road staffers and participants crisscrossed the room around us. Lauren had no prior background in disability services. Her practice is in sculpture: assemblages of cotton jersey, jesmonite, wire, glass, or agricultural milk powder, to make objects that sit on gallery floors or are suspended from walls. There are braided ropes in shiny ceramics, piles of flour carved with faces. It’s the kind of materially rich art that suggests a serious mind at play. Laura Aldridge, an artist who worked for Artlink, the Scottish charitable organization that sets up all kinds of art experiences for people with complex developmental disabilities, knew Lauren and her work, and invited her to join.

Alison Stirling, Artlink’s projects director, looks for an unadorned, openhanded curiosity in artist partners like Lauren—an interest in distilled sensation, in the kinds of phenomena that are shareable with those who attend Cherry Road: refracted light, experiments with sound. The subject matter lends itself to non-verbal communication, which is appropriate and adaptive for people with disabilities, you might say, except: Distilled sensation is the whole game for so many artists, is it not? Think of Robert Irwin, chasing the qualities of darkness or light in his monumental, spare sculptures—the subtlety of a radiant glow across a surface; the trick of shadow in the corner of a room. Or imagine standing underneath giant, room-scale fields of primary color, such as Who’s Afraid of Red, Yellow, and Blue 3. Artists are forever trying to pierce through language’s stilted imprecision, to access something beyond the classifying, categorizing mind.

But Lauren herself is not looking for a cathartic encounter, she told me. She is plainly interested in pure qualia, like many of the Cherry Road attendees. She’s after some affinity, some kind of “shared field.” She pushed her chair back from the lunch table, filled the kettle for tea before heading back to the workshop room. “You know—the feeling of wetness, not the formula for H2O.”

People like Elizabeth and Nicola are not posting on social media about disability rights. They are not testifying before government bodies. They are not able to take jobs that would place them in the public eye. They are invisible in the extreme. It’s notable, then, that partnership with people like them is entrusted not just to clinicians, social workers, and therapists, but also to artists. In the sensory workshop, a person at the far edge of the social contract encounters all the joyous, necessary inefficiencies of relationship and all the useless, urgent vitality of art. In many day centers and group homes throughout the world, mollifying, entertaining, and keeping disabled people busy is as good as it gets. Safety and security. But each encounter in the sensory workshop embodies a singular belief: that every human is a riot of adaptive capacity, no matter one’s outward form of communication. That a consciousness, alert and unpredictable, exists in each and every body, whether you can witness it or not. To be there and to pay proper attention, you have to hold your expectations in abeyance and instead look for interests. In the sensory workshop, everyone is trying to hang out in some way that circumvents the logocentric norm of human relations. To hang out and find an opening.

The most familiar inclusive form of architecture is the ramp, a glissando of physics meant to replace the rise of a staircase, making passage possible for strollers, wheelchairs, walkers, and other assistive gear. That simple feature, the inclined plane, has utterly transformed cities all over the world, making sidewalk corners newly traversable through curb cuts. The shape stands as an icon for other kinds of access too, and it was impossible to miss at the Human Threads exhibition at Tramway, an arts venue in Glasgow that I visited in the spring of 2022, before I went to Cherry Road. The show was made of artworks produced in the wake of sensory workshop sessions, small experiments that were then built at monumental scale for the cavernous space. An enormous, gently sloped cobalt-blue ramp lay near one wall, and a vocalist, Drew Wright, performed at the opening, plugging his mic into a speaker hidden under the ramp. Wright sang and spoke through the ramp with very low notes and meandering high ones. He manipulated the blue slope as if it were an instrument while two dozen people reclined or sat on it, somatic listeners to a great thrumming delivered by ears, but experienced via skin. Think of the ramp as a combination of floor speaker and waterbed, only with sound waves instead of liquid—a means for absorbing vibrations through the whole body. Underneath were giant transducers for delivering a tangible orchestra, made either from pre-recorded sounds or the occasional live performance.

The ramp was the work of Wendy Jacob, a Boston-based artist whose Fulbright fellowship at the Glasgow School of Art brought her to Cherry Road in 2015. Jacob has created many tactile surfaces like this: collaborating with an academic who researches the low-frequency communications of the California mantis shrimp; a deaf bicyclist whose rides are guided in part by somatic signals; throat singers; and, this time, Nicola, whose sensory joys are often aural, including hearing her own name said aloud. For the whole of the evening, the ramp either projected Wright’s singing or played sounds on a loop—including Nicola’s favored ones, optimized for shiver-inducing delivery. There were dozens of people, toddlers and old folks, on and off the ramp: in wheelchairs and on feet, lying flat with pillows behind their heads, holding hands or staring into space. Jacob had built a landscape-scale jukebox for the limbic system, born from an unusual friendship of shared interests and available to every passerby.

I sat with Alison, who had dreamed of this exhibition for close to twenty years. She was joined by her partner, her mother, and four siblings, including her sister Lyndy, whose life and care catalyzed Alison’s work and who arrived in a wheelchair that, over the course of the evening, she maneuvered on and off the ramp. I joined her and Alison there. Alison pointed out the various guests in attendance, as well as other artifacts and upcoming performances. There was an enormous, hundred-foot swath of black-and-white silk, a supersize version of the one I would see later at Cherry Road, forming a tent big enough to walk under, with fans gently moving the fabric. Elsewhere was a light installation and a giant obelisk that occasionally frothed bubbles or the smoke of dry ice. But the ramp was the social magnet of the evening. Alison, Lyndy, and I sat together until Nicola’s tea kettle revved underneath us to a pitch of tremulous vibration. We locked our widened eyes and Lyndy, without a sound, reached for my hand.

I think of my son on the verge of adulthood, his many idiosyncratic joys so evident, and his life, my whole family’s life, that will be marked by his need for support. My husband and I talk about it and make many forward-thinking decisions with this in mind. Last summer I hiked through the Texas hill country with my friend Claire, my kids’ godmother, and she said, out of nowhere: “Let us help you.” For heaven’s sake, let some friends come alongside you, she meant, and turn the long-term support for Graham into a formalized group affair. I surprised us both with a weird sob of relief. Graham probably won’t need a day center as his home base, but he’ll need all kinds of other creative support, especially when my husband and I die. Some will arrive from the state, some from schools and jobs, and some from family and friends, the ones whose assistance is plainly necessary but also, for many people, life-giving—if they can see it as such.

And isn’t the needfulness of any one life a spiky and unpredictable thing? Claire’s two neurotypical sons are my godchildren. And who knows? They may well need to call on me more, on balance. All the tangling over terminology is a distraction from the everyday materiality of assistance, given and received. The truth of disability—with its mismanaged and sometimes horrifying social histories, its grit in the gears of capital, its invitation to rethink an ideal of unfettered autonomy— is that it comes to collect each of us, somehow.

I got to see Nicola one last time before I left, with Laura Aldridge and another artist named Laura Spring. “That’s a yes, I think,” I heard one say to the other, trying to discern Nicola’s response to a question. There was a bright plastic lei of flowers hanging on the wall—would she like to hold it? A clap on the elbow often signaled an affirmative, they’d found. On and around the table were a triptych mirror, a microphone, a couple of Slinkies, some stuffed animals. A nature soundtrack alternated between wind and water, and the artists quickly filled a couple of oversize balloons with an electric pump. Over the course of forty-five minutes, Nicola side-hugged one or both of the women, looping her elbows around their necks, smelling their hair. “Never been so much like a cat as now,” Laura Spring said, laughing. Spring reached for one of those wire head massagers, trying it out on Nicola. Heads were interesting to her, so they started thinking about how to build on the interest. The session was coming to a close. I lightly batted away one of the balloons, watching. Laura Aldridge tried on a glittery gold shower cap and sat down, chin in hand. If not hats, perhaps Nicola was interested in hair. “Maybe we should try a wig?”