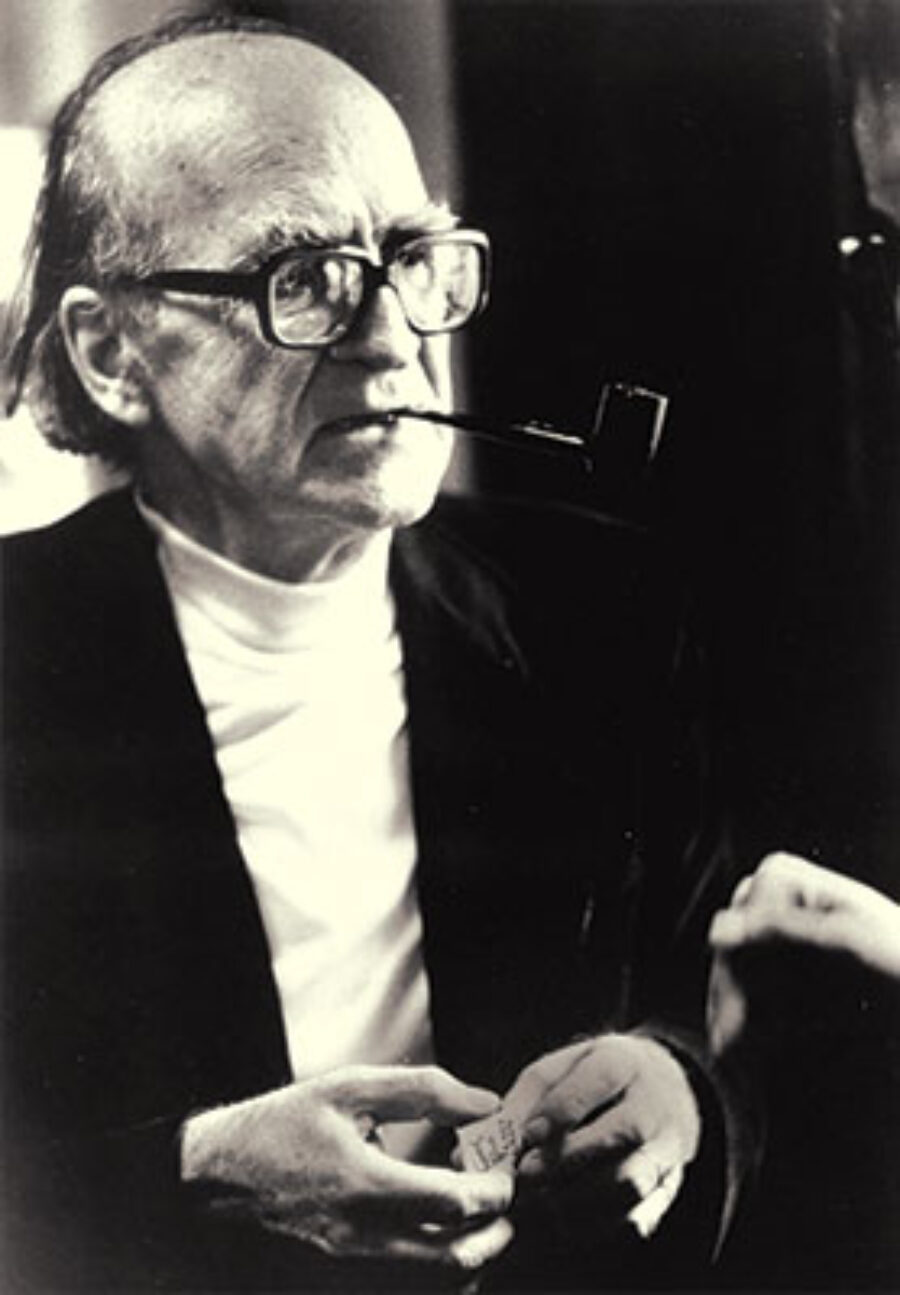

Mircea Eliade. Courtesy Hanna Holborn Gray Special Collections Research Center, University of Chicago Library

New Books

On May 21, 1991, in the third-floor men’s room at the University of Chicago Divinity School, a student noticed a hand dangling beneath one of the partitions, already turning blue. In the fourth stall, Ioan Petru Culianu, a Romanian professor of religious history, had been shot once through the head and left to die in a pool of his own blood, his pants still down. His killer was never caught, and the motive seemed to lie in some macabre interplay of politics and passion—the sort of fate that, in the American imagination, could only befall a foreigner. Some believed Culianu’s polemics had gotten him assassinated by the Romanian Securitate. The FBI noted that his occultist scholarship “was attractive to ‘wackos’ ” and that he “may have been accused of being a homosexual” because of his accent. “At one lecture in France,” a magazine piece reported, “three self-identified witches objected to his topic.”

Less than a week before his murder, Culianu, then forty-one, had safeguarded a sheaf of papers that could have shed light on the circumstances of his death. These wound up in the hands of his colleague Bruce Lincoln, who recognized them as translations of obscure articles by their mutual mentor, Mircea Eliade—himself a Romanian historian of religion whose emphasis on ritual and myth had redefined the discipline. Eliade, who died in 1986, had long been chased by accusations of fascism and anti-Semitism; he was rumored to have been involved with the Iron Guard, the militant wing of the ultranationalist group the Legion of the Archangel Michael, whose adherents, Lincoln writes, “construed themselves as a mystic order of soldiers and would-be martyrs.” In the Thirties, the legionaries, as they were known, had launched pogroms that claimed hundreds of Jewish lives. Eliade had steadfastly denied all but the most peripheral connection to the group.

Out of “some haunted mix of half-knowledge, anxiety, and sorrow,” Lincoln filed the translations for more than two decades before accidentally chucking them. Where most of us would shrug and walk away, he “decided that the only responsible course of action was to learn Romanian, locate the original articles, translate and study them myself, and make the results available.” Secrets, Lies, and Consequences: A Great Scholar’s Hidden Past and His Protégé’s Unsolved Murder (Oxford University Press, $29.95) is the fruit of his efforts to, in his words, “atone for my lapses.” It’s a study of vanity and deception—of the shifting allegiances, fears, and resentments that fuel academic reputation laundering.

To break the suspense: Eliade was an anti-Semite and a full member of the Iron Guard. His fifteen articles for Romanian right-wing dailies, long difficult to come by, stop short of embracing the Legion’s deepest brutalities, but unequivocally endorse its “Christian revolution . . . in the breast of this community of blood.” The son of an army officer, Eliade believed that cosmopolitan modernity (of the sort he considered imported by the Jewish professional class) had neutered interwar Romania. Only a concerted return to faith could save the nation from “a slow, larval, humiliating evolution” like that of Western Europe’s. A proponent of atavism and mysticism—he’d written his dissertation on yoga—he encouraged “a pagan thirst for a new life.” Writing in 1934, Eliade suggested that “the man who prepares himself for revolution is a man of mystery.” He applauded the operatic rituals of the legionaries, who fastened small sacks of Romanian earth around their throats as they vowed to defend “the endangered Fatherland.” Eliade strained to portray the movement as salvific when it was in fact homicidal. After one legionary defected, Lincoln writes, ten others

entered the hospital room where [he] was recovering from surgery, shot him more than a hundred times, dismembered his body with an ax, then sang and danced around his mangled corpse while waiting for the police.

Eliade told a friend that the murder “disgusted” him, but he continued to praise the Iron Guard in print, believing that only the legionaries could prevent a Romania “wasted by squalor and syphilis, overrun by Jews.”

Culianu discovered Eliade’s books in the Communist Romania of the Sixties and Seventies, a context in which the elder scholar’s rhetoric—about “the supremely creative power of sacrifice, the value of ascetic withdrawal, and thesacred nature of martial virility,” as Lincoln puts it—was appealingly reactionary. By then, Eliade’s strident pro-legionary articles were long buried, and he was ensconced at the University of Chicago, where Americans ignorant of Romanian politics looked upon him as a benevolent, disheveled genius. He was known for never reading the papers. Culianu started a correspondence with Eliade and soon left Romania to study under him. Lincoln recalls “an eager, intense, and intelligent young man, but lonely, guarded, and somewhat awkward.”

In the mid-Seventies, Culianu wrote his first book about Eliade, on whom he felt his career depended; he said definitively, and wrongly, that “any direct connection of Eliade with the legionary movement” was “to be rejected.” Privately, though, he nursed misgivings about his professor’s past. “I am reading For My Legionaries with despair,” he wrote in his journal, and was

exasperated by its delirious anti-Semitism. . . . The surprise that Mircea Eliade was the partisan of a totalitarian movement and that he remained for all his life a believer in its mythology fills me with bitterness.

Culianu swallowed that bitterness, and Eliade discouraged him from further investigation; soon Culianu had accepted his role as “the idiot disciple.” When the pair collaborated on a book about Eliade’s philosophy, Culianu fairly groveled. “You are undoubtedly the most extraordinary man I have ever met,” he wrote to Eliade. “You have a Mephistophelian intelligence under the appearance of an innocent dove. . . . Why have you still not received the Nobel Prize?”

Could this sycophancy explain how Culianu came to lie dead in a bathroom stall? Just as Eliade elevated the Iron Guard while looking away from its barbarism, Culianu spent the years after Eliade’s death making minor concessions about his champion’s politics without owning up to the extent of the harm he’d done. This balancing act had its price. Eliade’s widow, in particular, loathed anyone who besmirched even the shadow of her husband’s legacy. The day after Culianu’s murder, she told a visitor, “I never really liked him.” Lincoln finds it imaginable, if not probable, that she or another of Chicago’s legionary sympathizers arranged the hit. He’s not convinced that Romania’s secret police did the job—Culianu was simply too marginal a figure to require “liquidation,” as one former Securitate officer called it.

Lacking a definitive answer, Lincoln offers an artful dissection of the possibilities, conducted with the objectivity of a historian and the subjectivity of someone who was there. It’s moving to see how and when he allows his “anger, bewilderment, and regret” to pierce the book. His epigraph, from an Eliade essay called “Secrets,” has the sharpest point: “A ‘sin’ is surely serious, but if it is not confessed, it becomes terrible, as the magic forces provoked by the secret end by menacing the entire community.”

McLean Asylum, Belmont, Massachusetts, 1901. Courtesy the National Park Service, Frederick Law Olmsted National Historic Site

Some 150 years earlier and a thousand miles away, a different set of magic forces brought scandal to the Harvard Divinity School. In the fall of 1838, Jones Very, a twenty-five-year-old Greek tutor and nascent transcendentalist, announced to his students that he was “the second coming.” “Flee to the mountains,” he shouted, “for the end of all things is at hand!” Among the first things to end was Very’s university career. Believing him insane, Harvard sent him home to his mother in Salem, Massachusetts, where, “intoxicated with the Holy Ghost,” he attempted to baptize local ministers until they shoved him from their homes. He was briefly institutionalized but remained convinced that his every motion was “in obedience to the Spirit,” and that his own desires should be exterminated. After he was released, sonnets poured forth from him in gleaming, divinely dictated torrents—one observer recalled “a monstrous folio sheet of paper, on which were four double columns”—prompting Ralph Waldo Emerson to tell him, “Do not, I beg of you, let a whisper or sigh of the Muse go unattended to, or unrecorded.”

In God’s Scrivener: the Madness and Meaning of Jones Very (The University of Chicago Press, $35), Clark Davis, an English professor, contends that Very’s “season of spiritual ecstasy” enshrines a moment when “the fullest development of romantic individualism meets one of the earliest expressions of modern isolation.” Here was a poet who could run his hand through the flowers and lock himself in his bedroom for months. In Davis’s eyes, Very may actually have been sane, albeit sensitive. The early deaths of his father and his blind younger brother gave him a lifelong morbidity. His Harvard classmates remembered an undergraduate “in a state of poetical and spiritual exaltation” with “a solemn, not-to-be-trifled-with awkwardness.” He aspired “to restore epic poetry,” and so feared his attraction to women that he resolved to stop looking at or speaking to them. In his senior year, he felt what he described as a “change of heart, which tells us that all we have belongs to God, and that we ought to have no will of our own.”

Two months before his messianic break, Very attended Emerson’s controversial “Divinity School Address” and heeded his call to become “a newborn bard of the Holy Ghost.” His poem “The New Birth” found him in febrile metamorphosis:

’Tis a new life—thoughts move not as they did

With slow uncertain steps across my mind,

In thronging haste fast pressing on they bid

The portals open to the viewless wind;

What Very wanted, Davis writes, was to live as “a sort of half-conscious marionette moving in frictionless harmony with nature itself.” This made him elusive, sometimes arrogant. After he’d “gained the fame of being cracked,” as his student put it, and returned to Massachusetts society, his condition split public opinion. Nathaniel Hawthorne, for one, was flummoxed by his smoldering piety, writing, “Jones Very stood alone, within a circle which no other of mortal race could enter, nor himself escape from.” Emerson, who put together a book of Very’s poems and essays, was more sympathetic—he liked that his friend put polite company on edge. “He would as soon embrace a black Egyptian mummy as Socrates,” he wrote, comparing Very to “a corpse in the apartment”: “I wish the whole world were as mad as he.”

What’s remarkable about Very’s condition is its impermanence. After a few years circling “the life-rejecting cul-de-sac,” Davis writes, he settled down to an ordinary existence as a substitute minister for the Unitarian Church. If he regretted his Second Coming spree, he never let on. People spotted him taking long walks in a dark suit or perched in news offices, where editors let him read the out-of-town papers. The mystic had become mundane. He died in 1880.

Part of Davis’s project is to correct the unbridled speculation that tainted previous biographies of Very, especially Edwin Gittleman’s damningly subtitled Jones Very: The Effective Years, 1833–1840. Davis gives us the ineffective years too, and urges the reader to “recognize the limits of what we can know,” peppering the book with disclaimers like “it’s difficult to say with any precision exactly when Very began writing poetry,” and “few notable events shaped the final decades of Very’s life.” Better to peer into these lacunae, he suggests, than to fashion Very into the madhouse poet we wish him to have been. He laments that Very’s life is “often misread as the story of a Salem eccentric more amusing than important”—but these qualities aren’t mutually exclusive. I was touched by Very’s desire to “cut down the corrupt tree” in himself, and I had to laugh when he refused to allow Emerson to correct his poems. As the latter wondered to a friend: “Cannot the spirit parse and spell?”

The Resurrection, circa 1805, by William Blake © President and Fellows of Harvard College. Courtesy Harvard Art Museums/Fogg Museum, Bequest of Grenville L. Winthrop

Compared with Very’s and Eliade’s, the Christianity humming beneath Andrew S. Jacobs’s Gospel Thrillers: Conspiracy, Fiction, and the Vulnerable Bible (Cambridge University Press, $39.99) is positively cookie-cutter. Jacobs (also of Harvard Divinity School) has surveyed a subgenre of novels from the Sixties and Seventies that share a plot device: the resurgence of a lost first-century gospel whose revelations—“beyond anything that could be imagined by the mind of man,” according to one such book—threaten to sunder Christendom as we know it.

Such novels were and remain wildly popular; in 1972, Irving Wallace’s The Word, among the most famous of the bunch, topped bestseller lists and was condensed over three installments in Ladies’ Home Journal. Jacobs attributes their success to American anxieties about what the Bible meant—who determined its authority and which version of it was “true.” In the early Fifties, the National Council of the Churches of Christ had issued the Revised Standard Version (RSV), a new translation designed to be more accessible to all Protestant denominations. In pews across the nation, it met with a frosty reception: critics accused a “Protestant conglomerate,” Jacobs writes, of vying for a unified “super-church” whose top-down conformity smacked of Catholicism. A United States Air Force Reserve manual warned that “Communists and Communist fellow-travelers have successfully infiltrated our churches” through the RSV. This paranoia was not assuaged by the recently discovered Dead Sea Scrolls—which, “dramatically buried in antiquity and unearthed in modernity,” really did challenge the stability of the biblical text—nor by a 1963 Supreme Court ruling that prohibited mandatory Bible recitations in public schools. In midcentury America, the Good Book was everywhere in jeopardy.

Hence the gospel thrillers, with titles like The Judas Gospel, The Pontius Pilate Papers, The Dead Sea Cipher, and The Q Document (no relation to the Trump insider)—all chockablock with faded Aramaic, tattered forgeries, swashbuckling archaeologists, imperiled scholars, Nazis, Commies, and tough Israeli beauties with “chocolate brown eyes.” The new gospels, if their authors choose to reveal them, often have something to do with Jesus surviving his crucifixion or failing to resurrect himself; they’re sometimes exposed as fraudulent. It doesn’t matter, really, because, as Jacobs points out, the purpose of these thrillers is to preserve the status quo. Whatever mysteries the past holds, they say, Jesus will go on Jesusing. The climax of The Word—a rousing vision of humankind immersed in “the new Christ”—reads like one of Eliade’s crypto-fascist riffs:

If you went shopping, visited a bar, dined in a restaurant, attended a party, you heard it discussed. The drums beat, and the charismatic new Christ was gathering souls again, souls without number. . . . The general well-being and euphoria and brotherhood sweeping the earth were heralded by the recently awakened as the work of Christ.

If this is how the end of all things shakes out, I’ll do as Very commanded and flee to the mountains.