Your Mind’s in the Hands of Everything

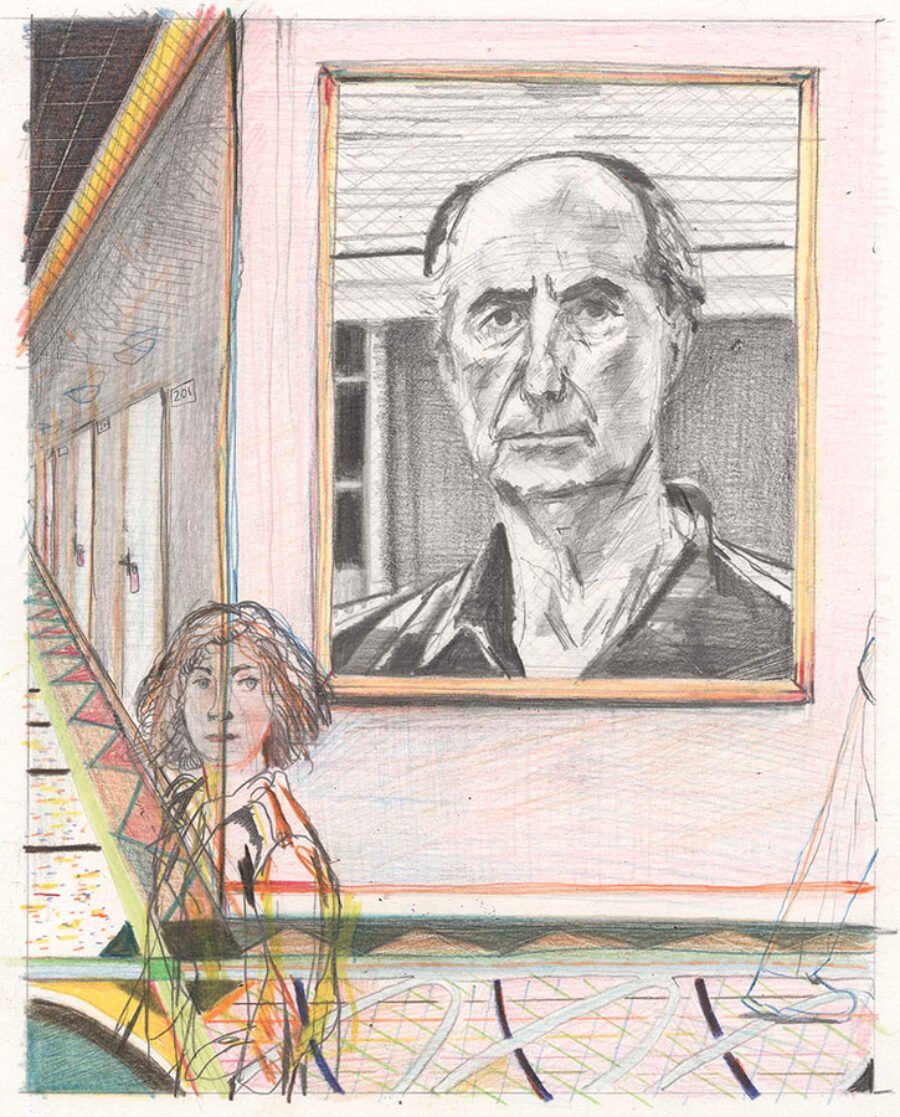

Illustrations by Yann Kebbi

It is difficult to predict when one will spend the night at a hotel in Newark, let alone three, and uncommon to agree to such a scenario willingly. If you live there already, you stay home. If you’re there for a professional engagement, your boss made you go. If your flight has been canceled, you go there as a last resort. Whereas, though I felt compelled to be there, I couldn’t point to an authority outside of myself that had forced my hand. The room had been booked a week in advance.

I was in town, in March, for Philip Roth Unbound, a weekend-long festival hosted by the New Jersey Performing Arts Center, on the occasion of what would have been the author’s ninetieth birthday. A decade earlier, Roth had celebrated his eightieth in his hometown, with an elaborate party at the Newark Museum. He sat beside the podium and read from Sabbath’s Theater. “He was very much the author of his own birthday party,” David Remnick reported then, “and he seemed to enjoy it to the last.” This time, though, Roth’s allies and acolytes would need to put on the show all by themselves. What would it mean to reinscribe the decades of life and work within a context that the author has left behind? By the time I arrived in Newark, the night before the festival, I was already thinking of my destination as “Rothdom”—someplace sovereign, provincial, and nostalgic, the physical instantiation of a reigning sensibility.

Roth is one of those rare writers whose absence isn’t merely noted but felt, and not just mournfully. His is a complicated absence. The festival aimed to reintroduce Roth to an audience of quarrelsome readers he could no longer argue with himself. The organizers promised “provocative conversations” and “spirited public debates that will explore and sometimes challenge the significance and impact of Roth’s singular literary legacy,” delivered by a diverse roster of intellectuals. A few had even been his friends, among them the writer Claudia Roth Pierpont (no relation), from whose biography of Roth the festival drew its name. Some of these panelists would be reconsidering Roth’s work in light of the feminist and racial justice movements that gained traction around the time of his death, as well as the “cancel culture” discourse that gobbled up much of that traction. Another specter—though not explicitly mentioned in any festival literature—would be the disastrous Roth biography published in 2021. Omitted from the weekend’s broad-minded lineup was Blake Bailey, its author.

A few weeks after Bailey, also Richard Yates’s and John Cheever’s biographer, published Philip Roth: The Biography, several women, some of whom Bailey had taught when they were in middle school, accused him of sexual assault, harassment, and grooming. Bailey’s publishers at W. W. Norton canceled the book shortly thereafter. (It was then picked up by Skyhorse Publishing, a conservative press whose recent output includes books by Robert F. Kennedy Jr. and Woody Allen.) Roth, who’d chosen and trusted Bailey to burnish his legacy, had his reputation dragged into the crossfire.

In the wake of Roth’s death in 2018, alongside the triumphant hagiographies, further reconsiderations of misogyny in his writing were composed, and new ones were occasioned by the Bailey scandal. When I think about what might account for this public recalibration, as well as the magnitude of Roth’s creative achievement, the word “controlling” comes to mind. When he began publishing the stories of Goodbye, Columbus in his mid-twenties, Roth’s fascination with the art of public persona, later thoroughly mined in novels like Operation Shylock and I Married a Communist, had already taken hold of the self-proclaimed “boy wonder.” As the years wore on and several of his novels, most notably Portnoy’s Complaint, earned him massive, controversial press, he became increasingly preoccupied not only with his own legacy but with those of writers who seemed to him like alternate versions of himself—namely Jewish male writers of cosmopolitan America and Communist Czechoslovakia. Chroniclers of Roth’s life note, sometimes inadvertently, that he kept many of his translators, editors, (ex)girlfriends, contemporaries, and groupies on a very short leash, to both glorious and detrimental effect.

Above all, Roth was controlling in the work itself, not just disciplined but sequestered in a process of enchantment. In 1984, the great biographer and friend of Roth’s Hermione Lee conducted his interview for The Paris Review, which Lee has claimed Roth took more than six months to edit with her. In the published version, when Lee asks Roth if he thinks his writing has had an impact on the culture, he replies, “No.” “If you ask if I want my fiction to change anything in the culture, the answer is still no.” He goes on:

What I want is to possess my readers while they are reading my book—if I can, to possess them in ways that other writers don’t. Then let them return, just as they were, to a world where everybody else is working to change, persuade, tempt, and control them.

It was Roth’s MO to craft a fictional truth convincing enough for the reader to resist the given world and succumb to his. My only quibble is with his desire to return the reader “just as they were.” That hasn’t been the case for me. My perception of the world changed from the moment I started reading Roth. It isn’t as though I’m going around wanting to shout into a phone or fuck in a grotto, but that I see things I hadn’t before, and some of them aren’t even there. Which is another way of saying that reading his work has honed my imaginative faculties, as well as my paranoiac ones.

I first encountered Roth’s writing when a high school English teacher assigned The Human Stain to me, specifically, as extra credit. The novel won me over with its argumentative, sumptuous language and antischool credo. (It would not have occurred to me at the time that Roth was in part reacting against campus feminists.) I read it with the sensibility of a quiet, solitary student. Some of what thrilled me I’d already encountered in The Scarlet Letter, The Great Gatsby, and Nella Larsen’s Passing; these novels gratified and complicated my intuition that people were not who they presented themselves to be, and that it was cruel on the part of society to punish its members for these incongruencies. Unconsciously I lusted after an intimate relationship to language that could flourish outside of institutional life, where I hardly ever discovered the playfulness, sympathy, or kindness I craved. Still, few of the authors I read during those years captured my imagination and became my companion throughout adulthood the way Roth did. Roth had written The Human Stain at a time when he had the power to transform the thinnest of emotional pretenses—a gleefully juvenile hatred of political correctness, and a hilarious but cloying identification with Bill Clinton’s fall from grace—into a furnace of seduction.

Over the years, as I made my way through his novels and came to identify as a writer—first as a journalist and critic, now also as a fiction writer—I found myself in and around situations that seemed Rothian: skirmishes with editors, legal proceedings with a literary bent, dates with men who idolized Roth, the surreal agonies of having the same name as another writer, nemeses arriving in all shapes and sizes and none so fearsome as myself. A line of Alex Portnoy’s seems apt: “Doctor, maybe other patients dream—with me, everything happens. I have a life without latent content. The dream thing happens!” At least that’s how it sometimes feels. The mechanism in the mind that makes the writing and the dreams, in which strange and significant images are always surfacing, can’t kill its engine peacefully at the border between fiction and reality and simply take in the view.

Flipping through the festival literature, I wondered if other longtime readers of Roth operated similarly, and, if so, what cohesion might be possible among an assemblage of such neurotics. Could the panelists and attendees together shepherd a stained legacy into the hands of new readers? Inevitably, the questions that hung over this ninetieth birthday weekend concerned a future centennial celebration—whether one would be thrown, and whether anyone would come.

I also formulated these questions of inheritance as a problem of influence. I can neither applaud nor dismiss the effects that Roth has had on my writing and on my life, and the fictional projections that his work helped set in motion long ago. So where did that leave me?

For now, in a strange bed no more than thirty miles from my Brooklyn apartment. I’ve long felt an affinity for hotels that has to do with their anonymity, the understanding that the room wasn’t designed with you in mind, or anyone else. Indeed, the floor I was staying on boasted only a single marker of context: Frankie Valli, whose face had been painted across a wall in the hallway. (Each level of the hotel was themed for a famous son or daughter of Newark.) When I saw that the room itself was a monotonous white, I greeted it with relief, but I came to rue my lack of options: an adjoining room, occupied by strangers, quickly filled with cigarette and weed fumes that wafted in through the gaps in our shared doorway, along with the booming noise of a man and a woman’s arguments I could only sometimes discern.

The festival was to conclude with a reading from a theatrical adaptation of Sabbath’s Theater, so that was the Roth novel I’d decided to bring with me, and the one I reached for at 2 am. The novel takes place over the course of three days, as the festival would. The protagonist, Mickey Sabbath, is a failed, arthritic puppeteer disgraced by a sex scandal; mourning the sudden loss of his extramarital soulmate, Drenka, to cancer; wavering on the verge of suicide; and receiving top marks as New England’s angriest horned-up cataclysm.

I hadn’t read Sabbath’s Theater in eight years, and the scenes returned to me with a bracing vividness, as once again I was gripped by the intimate residue in Roth’s writing. It’s in the sentences, which in Sabbath’s Theater confront the reader in close third, just about the closest I’ve ever experienced, like a camera flattened against an eyeball. “Ascetic Mickey Sabbath, at it still into his sixties. The Monk of Fucking. The Evangelist of Fornication. Ad majorem Dei gloriam.” And a bit of Drenka: “Everybody jerks their dick differently.” Every page surprising, vulnerable, invasive, overwhelmingly specific. Roth, like the puppeteer, sublimates his will to control in order to bring about a narrative state that feels anarchic. In this way, repression and chaos suit each other, hand in glove—at least so long as that hand is engaged in the writing process.

The next morning, after a couple hours’ sleep, I awoke to the sodden sounds of vomiting. After whining diplomatically to the front desk, I was moved to the sixth floor, where Roth’s huge, serious face, painted on the hallway wall, greeted me the moment I exited the elevator. My new room was nearly identical to the first, but quiet, as well as thematically consistent. Order had been restored.

Rothdom: the New Jersey Performing Arts Center, all cinnamon-brown brick and glass, stretches half a city block, and yet I only ever found one tiny corner of the elaborate structure with doors that opened. Like a ship at harbor laying out the gangplank. Except not so conspicuous. It was common to observe attendees pawing at the structure’s many decorative entranceways. The building contains a couple of theaters where many of the events were held, a restaurant where I never ate, an M. C. Escher–esque staircase, and rolling fields of carpet. Aside from the convention center, Rothdom also comprised two satellite event locations, both within a two-mile radius: the Newark Public Library and Hobby’s, a Jewish deli that’s been in business since the Sixties.

Rothdom: the New Jersey Performing Arts Center, all cinnamon-brown brick and glass, stretches half a city block, and yet I only ever found one tiny corner of the elaborate structure with doors that opened. Like a ship at harbor laying out the gangplank. Except not so conspicuous. It was common to observe attendees pawing at the structure’s many decorative entranceways. The building contains a couple of theaters where many of the events were held, a restaurant where I never ate, an M. C. Escher–esque staircase, and rolling fields of carpet. Aside from the convention center, Rothdom also comprised two satellite event locations, both within a two-mile radius: the Newark Public Library and Hobby’s, a Jewish deli that’s been in business since the Sixties.

On day one, a Friday, I had lunch at my hotel on a block formerly occupied by the Palace Chop House, where notorious mobster Dutch Schultz was gunned down in 1935. I was eating shrimp tacos and reading Sabbath’s Theater in one of the mini banquettes when a chatty group, of all ages, a few more men than women, wearing sweaters and vests in subdued palettes, congregated at the table directly across from mine. They were close enough for me to hear snippets of their conversation: “I’m writing my second book on Roth”; “It’s a class commentary!”; “But how much of that is just social conditioning?” One of them was carrying a tote bag with Roth’s name on it. I ordered a coffee, finished it, and decided to introduce myself.

I spoke first to two men, Andy and Noah, who seemed chummy with each other even though they’d met only that weekend. I asked if they were academics. “Can’t you tell?” Andy said, gesturing vaguely about. “The way we’re dressed? The drinks in the middle of the day? Care to have one?”

I demurred and asked if they were attending the festival. As it turned out, I had stumbled upon a dozen members of the Philip Roth Society, an academic group committed to the furtherance of Roth studies, with its own journal. This lot had just come from a different three-day Roth event for scholars that had taken place at the library. Many would be going home after lunch, but a few others were committed to the full six-day experience. I tried to place myself in the body of an academic who’d already been in this place for seventy-two hours and felt the tips of my fingers go numb.

When I told Noah, who teaches at a subsidiary of the CUNY system, that I was from the Upper West Side, he became giddy. (Roth bought a condo in the neighborhood, on West 79th Street, in the early Aughts.) Eyes shining, he asked if I’d ever been to the Patagonia store on Columbus between 80th and 81st. Of course I had. Well, I was informed, that’s the very Patagonia where Roth, according to legend, once paid for the coat of an attractive woman who was checking out ahead of him. Then Noah asked me if I knew the Shake Shack on the corner of 77th and Columbus. Yes, Noah, better than some apartments I grew up in. Apparently Roth took some special pleasure in sitting on a bench across the street from that Shake Shack. That bench is just a stone’s throw from the Nobel Monument, “which, of course,” another society member interjected gloomily, “his name is not inscribed upon.”

This was the first of several times over the weekend that Roth’s failure to secure a Nobel Prize was mentioned. And it reminded me that, despite the mountain of accolades heaped upon Roth in his lifetime, no American author’s fan base has ever felt more cheated on behalf of their champion, and perhaps sometimes themselves. For comparison, when Steinbeck won the Nobel, even he insisted he didn’t deserve the honor. Then again, Steinbeck was a little more relaxed than Roth. To this day he’s the only distinguished person of letters I’ve seen photographic proof of wearing a hoodie as early as the Fifties. Roth never wore hoodies and neither does a single one of his followers, as far as I’ve seen, at least not while in Rothdom. There everyone dressed like a lecturing professor or a golfing one. Bob Dylan, the Jew who caused the heads of every diehard Roth fan to quietly explode when he was awarded his Nobel, was invoked in my presence exactly once all weekend—by a man who wrote a book about him.

Several of the academics had attended Roth’s eightieth, and there was an air of something significant having been lost since they’d last congregated in Newark. The defender of their faith had perished. Bailey had assumed the throne, briefly, only to be deposed. The biography had only been meaningfully called to task, before the allegations, in a single review in The New Republic, by Laura Marsh, for its indulgent, at times misogynist and crass, belief in Roth’s version of events. Marsh’s colleague at the time, Jo Livingstone, wrote of the unfolding spectacle that it had been

compounded by the way Bailey and Roth occupy a similar position in the culture—very successful white literary men with a reputation for licentiousness—which makes their fates appear entwined.

Six weeks later, the New York Times published a reported piece, “What Happens to Philip Roth’s Legacy Now?,” in which scholars bemoaned the tarnishing of his reputation—as well as the potential inaccessibility of papers, shown exclusively to Bailey by Roth, to more promising researchers.

Bailey’s biography attests to the ways that Roth’s obsessive drive to manipulate became, if not stronger, then at least more desperate in his later years, as the tragicomic aspects of his nature came into relief. (As Philip Roth, the narrator of his thirteenth novel Operation Shylock, puts it, “a man’s character isn’t his fate; a man’s fate is the joke that his life plays on his character.”) He once offered one of his ex-girlfriends, the novelist Lisa Halliday, monthly payments in exchange for her not marrying her boyfriend (she declined Roth’s offer, but the two remained friends); a few years earlier, having gradually soured on Saul Bellow’s biographer, he tried ruthlessly to ruin the book’s prospects, going so far as to write a letter to Bellow, ordering him to:

Say nothing about the book to anyone outside the very inner circle. NOT A WORD. NOTHING. DON’T SHOW THE WOUND TO A SOUL. THIS IS THE DISCIPLINE REQUIRED.

He also fired his initial biographer more than a decade into the project and went with Bailey instead. According to Bailey, Roth’s ultimate approval had something to do with their agreeing that Ali MacGraw, in her Goodbye, Columbus era, was super hot.

The whole pitiful saga does have the ring of destiny calling at last, with nothing but kind words. But after all the critical backbiting, bitter breakups, vigilant scorekeeping, and rabbinical upset, it was full-throated agreement that Roth might have been wary of. His fans in academia, never keen on missing a lesson of the master, at times espoused a somewhat more tepid agreement. A former president of the Roth Society, a woman with long flyaway gray-blond hair named Aimee, expressed the group’s general dismay over the Bailey scandal and worried that young people wouldn’t be so eager to read Roth going forward, a sentiment I heard repeated in different forms throughout the weekend. I only ever heard Bailey’s name uttered once more at the festival, by Gary Shteyngart (“Blake Bailey’s horn-a-thon,” he said of the biography).

As I sailed away from the table, some of the Roth Society people wished me well and said I shouldn’t hesitate to become a member myself. It’s only thirty dollars per year. They could even waive the fee! I told them they should charge more.

Based purely anecdotally on what I saw growing up on the Upper West Side in the Nineties and early Aughts, I’d put the percentage of geriatric Philip Roth fans in any given population at around thirty percent. In Rothdom, of course, it was way higher. At the first panel on Roth’s literary influences, “Reading Myself and Others,” held at the Newark Public Library, I didn’t see anyone who wasn’t at least middle-aged, aside from me and my fellow reporters. Just about everyone in the room was white, and I don’t think it would be going out on a limb to submit that several of them were Jewish. The panel featured Pierpont, whose sharp book about Roth’s life leans heavily on close readings of his novels. She sat at a table with Steven J. Zipperstein, a historian writing his own biography of the author. Zipperstein kicked off the festival by reading a quote about Philip Roth and masturbation written by one of my ex-boyfriends. I was accepting my fate.

Zipperstein then went to bat for Roth’s 1972 novella The Breast. In all my years residing in strongholds of Roth fans (the Upper West Side, Brooklyn, Chicago), nobody has so much as acknowledged the existence of this book in my presence. It tells the story of a man who wakes up to discover he’s been transformed into a giant, sentient breast. It’s not very good. Yet at the time of its release Roth was convinced it was among his most accomplished works to date, and years later would become the only person in the world to describe the book as the best “transgender novel” ever written.

The panelists then put their biographical expertise to use by glossing the fiction writers who most inspired Roth, especially from a young age. Pierpont argued that Anne Frank’s diaries represented a crucial “counterlife” for Roth, who forever dwelled on the lives of brilliant writers destroyed or constrained by historical circumstance. (In Roth’s admirable eighth novel The Ghost Writer, from 1979, Nathan Zuckerman’s love interest, Amy Bellette, may or may not be Frank.) The two also discussed the importance for any writer, Roth especially, of listening carefully to their interlocutor; the exchange broke down entirely when Zipperstein inadvertently started telling a story he’d heard about Roth, which turned out to be one that Pierpont had originally told him. He blushed mightily and seemed chastened by the faux pas, which he never appeared to recover from. I had the sense watching Pierpont in action that there was a tiny button somewhere on the stage she could press at any time to devastate whomever she wished, only sometimes her target gallantly pressed it himself.

The high point was when moderator Sean Wilentz, the historian and author of the Bob Dylan book, decided quite unilaterally to close with a dramatic reading of—what else?—a passage from Sabbath’s Theater. The scene is part of a flashback detailing Sabbath’s fling with a young German woman named Christa, whom he wears down by making her listen to jazz, eventually convincing her to join a threesome with him and Drenka. Roth is adamant that Christa presents rather like a boy, with her hair “short as a Marine recruit’s” and a defiant attitude that Sabbath assiduously disarms. “[T]he kid was all business: no sentiment, no longings, no illusions, no follies, and, he’d bet his life on it—he had—no taboos to speak of.” For his performance, Wilentz required a bit of help from technology. A ceremonial young person emerged into a makeshift enclosure in the corner of the room, near a laptop that awaited his touch. He pressed play and The Famous 1938 Carnegie Hall Jazz Concert, the Benny Goodman album, wafted from the speakers. Wilentz read from a passage in which Sabbath provides commentary on “Honeysuckle Rose” as he and Christa listen to the Goodman tape in his car.

“ ‘This is jumpin’,’ Sabbath told her. ‘This is what’s called a foot mover. Keeps your feet movin.’ ”

Sabbath is struggling for relevance; his moves reek of naked desire crudely dressed in cultural proficiency. And yet, in a way, he still has the upper hand. It’s his fantasies that come to life, sometimes with terrible consequences. It occurred to me that reading a passage about a lascivious old man explaining jazz to a pretty young woman was rather like preaching to the choir here in Rothdom, where—with my short hair, my leather jacket, my severe little smirk—I was loath to admit that I was the only plausible representation of Christa in the room. Afterward I went up to Pierpont, told her I was reporting on the event, that I appreciated how she’d handled herself on the panel and enjoyed her book on Roth. She thanked me and asked if I was in college.

It wasn’t too long before I was back at the hotel restaurant eating chicken parm. I’d come straight there from my final event of the day: a reading of Roth’s shorter works that included a performance by Matthew Broderick, in which he waffled between two different pronunciations of “Kafka” for twenty minutes. It was an evening of seasoned actors barreling through and occasionally stumbling over words.

This was my second hint of the day that there’s something off about reading Roth aloud. Not in the privacy of one’s own room, perhaps—at least in my experience—but in front of an audience, where it becomes difficult to find one’s way to the emotional force of it. In front of an audience, the words shriek and occlude, like a closet full of bats that has unfortunately been opened.

The pattern of little to no sleep repeated itself. My eyes flitted from the sunrise over Newark to the page, where Sabbath recalls what it was like to be intimate with Drenka. She talks dirty to him:

“You know what I want next time you get a hard-on?”

“I don’t know what month that will be. Tell me now and I’ll never remember.”

“Well, I want you to stick it all the way up.”

“And then what?”

“Then turn me inside out over your cock. Like somebody peels off a glove.”

I tried to pack up my body and store it away, but it was made of the same stuff that tanks are made of and wouldn’t obey. Not, at least, until I attended the morning and early-afternoon panels, which skewed indignant and cerebral, their concerns finely calibrated to the kind of buzzy publishing discourse—cancel culture, teaching literature to zoomers, book deals—that gives any writer who desires it a claim to moral outrage.

The headline of the day was that writers are under threat from social media, teenagers, stupidity, and capitalism, but that they will persist for the sake of beauty, imagination, and gossip. The audience was particularly responsive to assertions that literature still matters but underwhelmed by references to beating off with a piece of liver, probably because they’d been beat over the head with the joke at every previous event already.

We knew that men could cum, but could they write fiction about women? Can a Jewish man write fiction about a black man passing as a Jewish man in academia? This was the explicit subject of one of the day’s panels, “What Gives You the Right?,” which began with a brief discussion of cultural appropriation in The Human Stain and concluded in a delicious mudslide of grievances. The panel, moderated by essayist Meghan Daum, featured novelist Jean Hanff Korelitz, longtime Atlantic contributor Hanna Rosin, and critic Lauren Michele Jackson. The panelists saw a shadow creeping across the domain of free fictional expression—though Jackson, the youngest and the only person of color on stage, offered on most matters deftly measured complications or rebuttals, and tried to steer the conversation away from the easiest targets. Others weren’t convinced The Human Stain would be published today. While taking notes on the panel I erroneously retitled it “What Are We Allowed to Do Again?”

In an effort to bring The Human Stain and its critiques into the present day, much of the discussion focused on the controversy surrounding Jeanine Cummins’s 2020 novel American Dirt, which imagines a Mexican family’s harrowing migration across the border. The novel, backed by a six-figure marketing budget, remained on the New York Times bestseller list for thirty-six weeks despite some eviscerating reviews, including one by then–Times critic Parul Sehgal, who argued that the author had not demonstrated the necessary skill to depict characters whose experience she had painstakingly researched but not lived herself.

Fairly or not, American Dirt has become synonymous with cultural appropriation, although, as Jackson noted, it also “laid bare the unfortunate mechanism that is major publishing in America,” in which one book is “crowned belle of the ball” while other authors “scramble to fill seats at their local bookstore reading.” Meanwhile, the dustup helped usher into popular imagination the recent phenomenon of sensitivity readers, who tend to be young, queer people of color contracted by Big Five publishers to weed out culturally insensitive or inflammatory material from their books.

The very idea of sensitivity readers disturbed most of the panelists. “Why aren’t publishers doing their jobs?” Daum asked. “Their job is to read a bunch of manuscripts and be English majors.” She claimed to know several authors whose books publishers had shied away from so as to avoid a reception similar to that of American Dirt. Korelitz responded by telling a story about how she changed a fictional character’s West Indian ethnicity at the behest of a sensitivity reader. The punch line—“I made her Irish”—elicited a thunderous gasp from the audience.

What every panelist expressed, regardless of her position, was a great deal of uncertainty that they, or any writer, could exert control over the shape of their careers, much less what kind of legacy they might leave behind. In the crush of competition among writers struggling to make any name for themselves at all, Roth represented the possibility of awesome talent recognized and elevated above the fray. But wealthy publishers with fat checks for the select few had been, for him, a favorable state of affairs. Now it’s the status quo. Had The Human Stain been published today, how much more would he have been paid for it?

At every other panel I attended, audience members were encouraged to write down their questions on tiny index cards, but for some reason, as “What Gives You the Right?” wound down, two microphones were stationed at either end of the room. The horde of Roth fans saw their opportunity and did not squander it. Below is a sampling of the “questions” posed to the panelists:

“Who can someone else write about? I mean, can I not write about men?”

“Doesn’t it fly in the face of literary history? Since at least the nineteenth century, you have Gustave Flaubert writing Madame Bovary—how the hell does he know what a woman feels like?”

“Who exactly are these ‘sensitivity readers’? Where do they come from?”

“Is everyone just afraid?”

And my personal favorite: the man who had a bone to pick with whomever had cast Nicole Kidman as Faunia in the film adaptation of The Human Stain. “The woman in the book was not a Nicole Kidman type,” he explained. “It was clear that producers just wanted to have Nicole Kidman, or someone who looked like Nicole Kidman, to bring people into the theater.” Faunia, he insisted, “bore no resemblance whatsoever to a tall, six-foot, beautiful blonde like Nicole!” A wave of excited chatter rolled through the audience, as if a star prosecutor had just submitted incriminating evidence to a courtroom.

These are Roth’s people, I thought while surveying the crowd, the ones who love books and go around shouting about how nobody believes books matter anymore. The embattled, the aggrieved, the non–Nobel Prize winners. The ones whose brittle hearts crack open and douse their insides with unabashed animus at the merest glimpse of Nicole Kidman’s face, as Roth himself no doubt experienced when he tried unsuccessfully to get the actress to go on a date with him in a limo. Their Rothian idol is waxen and sweats at the slightest application of heat, yet they’d rather prop him up than mold him into something else.

That afternoon I also attended “Letting the Repellent In,” featuring novelists Ottessa Moshfegh, Susan Choi, and Shteyngart, and moderated by novelist and playwright Ayad Akhtar. They discussed their admiration for Roth, and for literature as a place where it’s okay to be weak, disgusting, funny, and mortal; on this we all agree, in theory at least. “Is it ‘harm’ to make people feel uncomfortable?” Choi asked. The audience’s approving murmurs and tepid applause indicated that, no, it is not. Shteyngart, for his part, joked that he “would never touch” a sensitivity reader. “That’s insensitive,” he said. “But I am not Roth. Roth would probably do something like that.”

Toward the end of the discussion, Akhtar read from “Radiant Poison,” Vivian Gornick’s 2008 essay for this magazine, in which she charges Roth and his slightly older contemporary, Bellow, with a misogyny that blights their work and condemns it to future irrelevance. Gornick writes: “Somehow it’s hard to imagine yesterday’s savaging brilliance transforming into tomorrow’s wisdom.”

In response, the conversation shifted to how we should live with the failings of beloved authors. Moshfegh’s response resonated with me more than anything else said on the subject of misogyny that weekend, especially as some panelists denied its presence in Roth’s writing altogether. “Whatever I find distasteful and embarrassing,” she said, “I feel it’s embarrassing for the author.”

This is so efficient and confident I almost wanted to call it a day. Certainly it’s how I’d like to react to Roth’s worst—as in stingiest, least aesthetic, most polemical—tendencies. But it doesn’t really capture the feeling of reading Roth for those who are genuinely troubled by his work. Who actually feels this embarrassment? I wondered. Who bears its consequences, its weight? Especially since the author, who vociferously accepted none of it in his lifetime, is no longer around to blush.

Here I must defer to the younger version of myself who read The Ghost Writer, Portnoy’s Complaint, and The Human Stain, and came away fearing that I could one day become anything like Hope Lonoff, the Monkey, or Delphine Roux. They were the embarrassing ones: the servile wife, the pliable young woman, the disingenuous feminist scold. And yet it would have been my shame, not Roth’s, to never be foolish in love, devote myself to others, grow older, or yearn openly for a less hierarchical world. This is, I suppose, my own ill-advised defense of literature, or at least my diagnosis of its challenges: that it is not moral instruction, nor a basic need akin to shelter and food, but rather a need like friends, adversaries, and love. Its function is social, even when we’re alone with it; it works only insofar as we can live with it, become vulnerable to it, or resist it. I have no desire, then, to expunge charismatic sexism from the page. At times I have wished that its practitioners had to wear it like an ugly frock I could rend at any moment with my teeth and claws. But I’ve more often wished that with my own writing I could force Roth to laugh, ache, remember, regret—that our transformative encounter could somehow be mutual. I’d take the waxen idol and put the eyes on the shoulder blades, his hands on his head like a double coxcomb, and his heart on the outside. I want my desire for this profane image to be read as a libidinal drive, and a creative force in its own right, without its being reduced to righteousness or piety.

Occasionally, a woman with an Eastern European accent, such as Drenka, can avoid the full brunt of the trivial fate reserved for most of Roth’s female characters by assuming the reins of sex. For instance, there is the character of Jaga, the Polish immigrant whom Roth’s alter ego Nathan Zuckerman meets in The Anatomy Lesson at a hair restoration clinic where she works as a technician. Zuckerman, at forty, is suffering from some physical and psychological setbacks that restrict him to being fucked faceup on a mat by a revolving coterie of girlfriends. Jaga stands out from the pack, not for her ability to hold onto Zuckerman, but because she reflects richly upon the situation, enough to make me think she could have been a writer herself.

“I know writers,” she says to him on the mat.

Beautiful feelings. They sweep you away with their beautiful feelings. But the feelings disappear quickly once you are no longer posing for them. Once they’ve got you figured out and written down, you go. All they give is their attention.

I have been the woman scorned and the writer who excised lovers from her life too callously. I have loved the glitzy merry-go-round of life, but not at the expense of my solitude in a charmless room. It’s when Roth gives to his female characters some of his own acuity, cruelty, lust, humor, and best lines that the constraints which keep them flattened and immobile within the narrative loosen. Then they are agents and sufferers of psychic mayhem, devils in their own right, unbound.

Chilled air and a spotless sky greeted what would have been Roth’s ninetieth birthday. In my room, Sabbath was remembering the time he spent jerking off to Conrad novels as a young seafarer. I went downstairs to eat the tiniest possible unit of potato from the hotel’s breakfast bar at what looked like a banquet table for a marauding band of mid-level executives. Soon my body was full and my soul was dancing just above it. I was more than ready to embark upon my sole mode of transportation around Newark that weekend: the Philip Roth bus tour.

The tour was led by Elizabeth Del Tufo, the president of Newark Landmarks, a tiny older woman in a black turtleneck and an Edie Sedgwick haircut. Her voice was at once commanding and raspy as she considered aloud whether Roth was her friend or just someone who responded to her phone messages. She had been heavily involved in the planning of his eightieth. (“I put together a fabulous party,” she told us.)

As we made our way from downtown Newark to the neighborhood of Weequahic—where Roth grew up middle-class in a jolly yellow house and attended the local public high school, where a handful of the passengers’ parents had also gone—Del Tufo asked her captive audience to read relevant quotes from Roth novels that were printed on a handout we had all received. The vibe was Ambulant Seder Table as we passed the New Jersey Bell Headquarters building, its façade still emblazoned with the names of former employees, now converted into rental apartments. The old Hahne’s department store had also become rental apartments, with a Whole Foods Market on the ground floor, and we were momentarily stuck behind a car loaded up with grocery deliveries for Amazon customers. Then came miles of dilapidated housing, churches, liquor stores, abandoned hotels, parklands, and the occasional repurposed synagogue. Abraham Lincoln was mentioned several times. In spite of his prominence in the city’s statuary and public spaces, however, there remains some anxiety about the president never having spent much time in Newark; he did pass through the city by train, but he stopped only to make a brief speech.* My fellow travelers and I were let off just once, at Roth’s childhood home. No stirring words were said, but we did take some very diplomatic selfies.

Next came the five-hour reading of Roth’s nineteenth novel The Plot Against America, conveniently held at the Victoria Theater in the NJPAC building, where the bus had deposited me. The book is the closest Roth got to writing his own extended fictionalization of Jews living through Nazism, an alternate history of the early Forties that hypothesizes what might have happened if the United States had elected a fascist leader and flirted with the idea of entering the war on the side of the Axis powers. It has a straightforward storyline mostly situated in Newark, a relatively quick pace, an atmosphere of political urgency, and a happy ending. It was adapted into a miniseries that premiered the week COVID-19 lockdown measures went into effect across the country.

Around me talk about 92nd Street Y events and the Broadway show Leopoldstadt whirled until the reading began. I would have liked to see Leopoldstadt just then. As with the other readings of Roth’s work I’d attended that weekend, this one revealed something unyielding in the text. Nine accomplished actors took turns with varying degrees of fluency, but no matter who read, all were subject to the sentences, and they leaned heavily on affecting outrage to get the sense of the words across. The language was not a canvas for the actors’ own talent; it was a gleaming tower of Rothdom they’d been condemned to climb.

When I took my seat for the next reading—this one of Sabbath’s Theater—a young woman in the same row as me pointed out that we had the same haircut. We were rare birds in this environment. She told me that at least a decade ago, while in college, she wrote a short story in which a former student reminisces on an affair she had with her professor: Philip Roth. Years later the protagonist senses his interest in her has dried up; he hasn’t alluded to her in any of his subsequent novels. She grows bitter and jealous. As the woman spoke I observed that aside from her having read loads of Roth, and the haircut, her affect was quite different from mine. She was rambunctious, fast-talking, a self-described “hedonist,” and boasted of reading her favorite passage from The Dying Animal to lovers. When I asked her how she felt toward the narrator of her own story, she appeared frazzled for a moment, her speech coming to a halt. Then she said, very carefully, that it seemed obvious to her that the character wanted to matter by being immortalized in someone else’s writing. Momentarily it seemed to me as if the protagonist she had written years ago had risen up before her eyes and was presently demanding acknowledgment. Or perhaps this was only a Rothian figment of my own imagination, the kind that spurs me in my own writing to reencounter myself again and again and twist the figure each time, until the singularity looks like a world.

The reading, with John Turturro as Sabbath, was the best I’d heard all weekend. Its brevity was a mercy but only because it had been such a long day. The scenes, lightly adapted for the stage, come toward the end of the novel, when Sabbath returns to his hometown on the Jersey shore to select his own plot in the cemetery where his parents and brother are buried. He also winds up encountering a cousin, named Fish, now one hundred years old. The characters are constantly mishearing and misremembering, or else dwelling, consciously, upon their defeats. Hearing the dialogue isolated and pared down, it almost sounded like Beckett.

“Okay, there was no fucking,” said the woman with the haircut in disappointed disbelief when it was over. Then Turturro and his collaborator Ariel Levy discussed their love of Roth’s writing and the process of adapting his novel. Despite all the extraordinarily bad cinema his novels had wrought, their enthusiasm caused me to wonder if we’ll be getting more Roth adaptations in the coming years. Can Roth conquer the Tonys? Perhaps a bevy of prestigious limited TV series will inch his legacy forward. Turturro told a story about rehearsing a one-man show of Portnoy’s Complaint while Roth stood in the back of the room wearing a raincoat.

A few minutes later we all left the room. No curtain fell. A curtain should have fallen! Preferably one made of recycled raincoats from the Patagonia on Columbus between 80th and 81st.

When I returned to the silence of my hotel room one final time, the passage from Sabbath’s Theater I love most was waiting for me. It appears not long before the selection that had just been dramatized at the Arts Center and is the one I would have most liked to see play out in front of me, because I can’t as yet picture how anyone would pull it off.

Sabbath, on his way to his former theatrical producer’s funeral, hurtling beneath lower Manhattan on the subway, half-recalls through the haze of his own erupting madness a scene from King Lear that closes Act IV, in which Lear, dispossessed of his kingdom, awakens in a French camp reunited with his daughter Cordelia. “You do me wrong to take me out o’ th’ grave,” says Lear to Cordelia, “Thou art a soul in bliss; but I am bound / Upon a wheel of fire, that my own tears / Do scald like molten lead.” In happier days Sabbath played the part of Lear opposite his first wife, Nikki, a gifted actress whom he has not seen in decades and who is presumed to be dead. For pages, Shakespeare mixes with Sabbath’s memories of Nikki and of his older brother, who died in the Philippines during the Second World War. “Methinks what?” muses Sabbath in his grief. “Methinking methoughts shouldn’t be hard. The mind is the perpetual motion machine. You’re not ever free of anything. Your mind’s in the hands of everything.”

It’s a passage unstable enough to remind you that Roth, the towering novelist, was a failed playwright as well. All his life he loved the theater; Shakespeare suffuses his work. But he struggled to get any of his scripts produced, and adaptations of his novels to stage and screen tend to go over poorly, just like the readings I had been sitting through all weekend. His novels are not like being in the darkened theater as Lear pronounces his coming doom, but like being in the darkness of Lear’s own mind as it invents a drama that persists despite that doom. They are novels suited to the dingy chamber in one’s psyche that’s closed against all others, even, at times, to oneself. How transfixing it is to follow the protesting passages alone in the shadows, like dreams. Nonetheless, I was glad to have seen the partisans of Rothdom emerge into the light, a little dazed, grasping the lyric force with clenched fists, with so much stubbornness and love.

Ultimately Sabbath is not Lear, and nor is Roth, who had no children. He understood himself as an heir to a line descending from Shakespeare to Kafka. Early in his career, with The Ghost Writer, he cast Nathan Zuckerman as a son in search of fathers and forebears; as time went on, his experienced and written life indicated that he preferred to manage his legacy rather than bequeath it. At the conclusion of the Sabbath’s Theater panel, the entire auditorium sang “Happy Birthday dear Philip Rooo-oooth,” as if we were at a party for children. It was one of the many reasons I left Newark with the strong impression of Roth as an eternal son. His work is this way, too: combative, labile, combustive with potential energy, and always striving to please, to be good, even when he’s being naughty. But now the wave has crested, the party is over. We’d encountered Roth encountering Roth, only this time we’d all done it in the same room. We’d felt the rightness of our positions wobble and be restored to us. The waxen idol had sweat all his wrinkles away so that he appeared fresh and relevant again. But how many more times, really, will we gather like this, with his overplayed hands interposed between us?

The festivities did not convince me that the weekend’s method of collective assessment and affirmation could chug along much longer—nor that a centennial celebration could predict the direction in which a reputation is headed. Roth is best sought in fits of astonishment on a subway bench or bed, “methinking methoughts.” There is no rule book of his we need to follow, no well-trodden path we need to take. I’d like to possess Roth in ways I’d hope to see more of his readers do as well: to take what creative, licentious force I need, and identify the Lear-ian corners in my own brain.

I packed up stormy, goatish Sabbath and left the hotel with my bags. Outside it was a clear night and I was returning home. I was in a car swiftly passing the Hackensack River, the Holland Tunnel, the Brooklyn Bridge, and at the same time I saw before me this distinguished son of Newark, his sentences like firm putty in my mind. I wanted to give them some other form, to claim, resist, and contaminate them, then release them back into the world, very much changed. My whole body went warm just imagining it, turning the words inside out over themselves the way that somebody—maybe you and maybe me—peels off a glove.