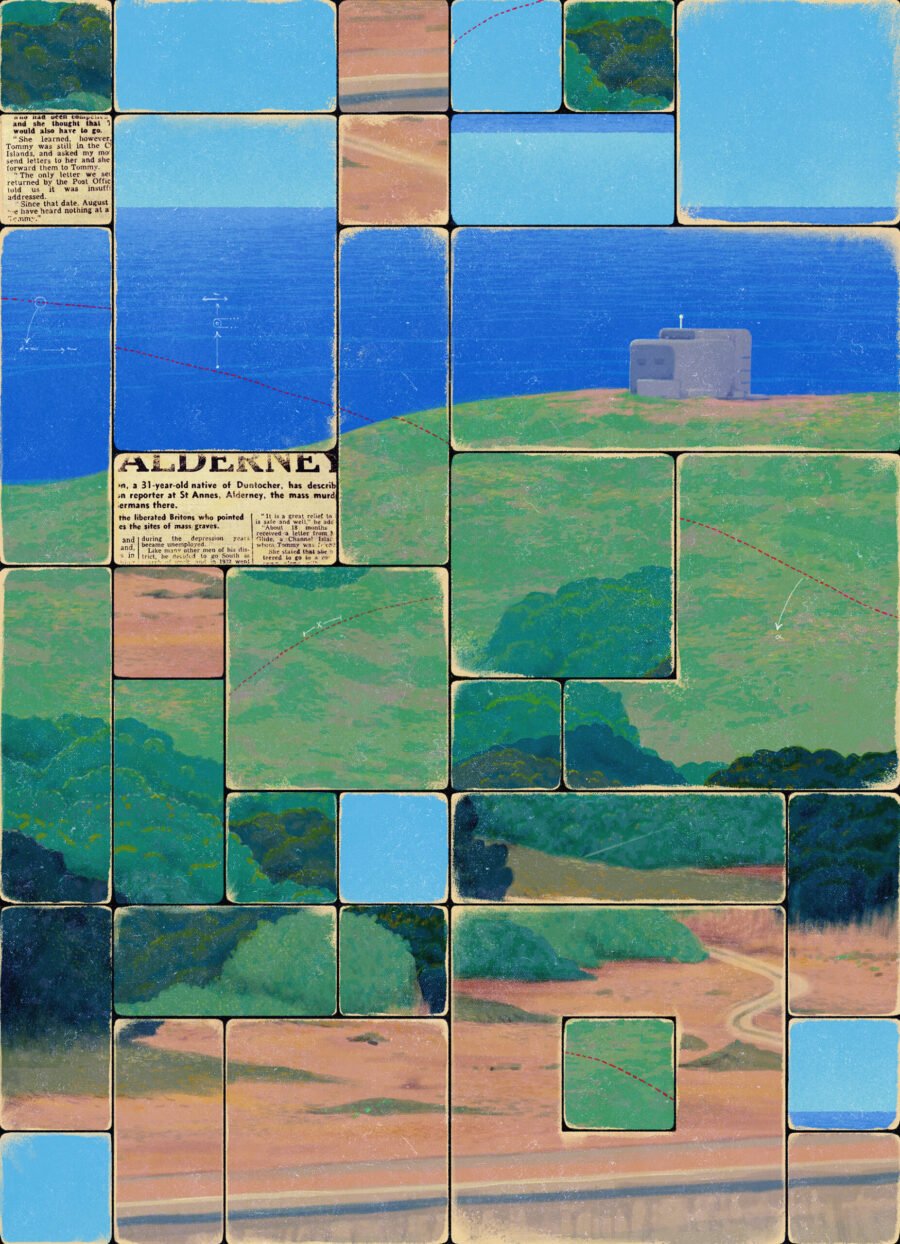

Illustrations by Daniel Liévano

Atop John Weigold’s mantle, flanked by a pair of candlesticks fashioned from antique fragmentation grenades, hangs a landscape, one of the few artifacts of the artistic career he retired early from paramilitary work to pursue. In it, a dark copper statue sits—its face obscured by the hood of an ankle-length cloak, like a grim reaper in repose—amid barren branches in the snow. The painting strikes a relatively pacific tone in a house filled with military memorabilia, but the statue itself is stationed outside a castle in Budapest’s City Park, where it depicts a twelfth-century notary who chronicled the history…