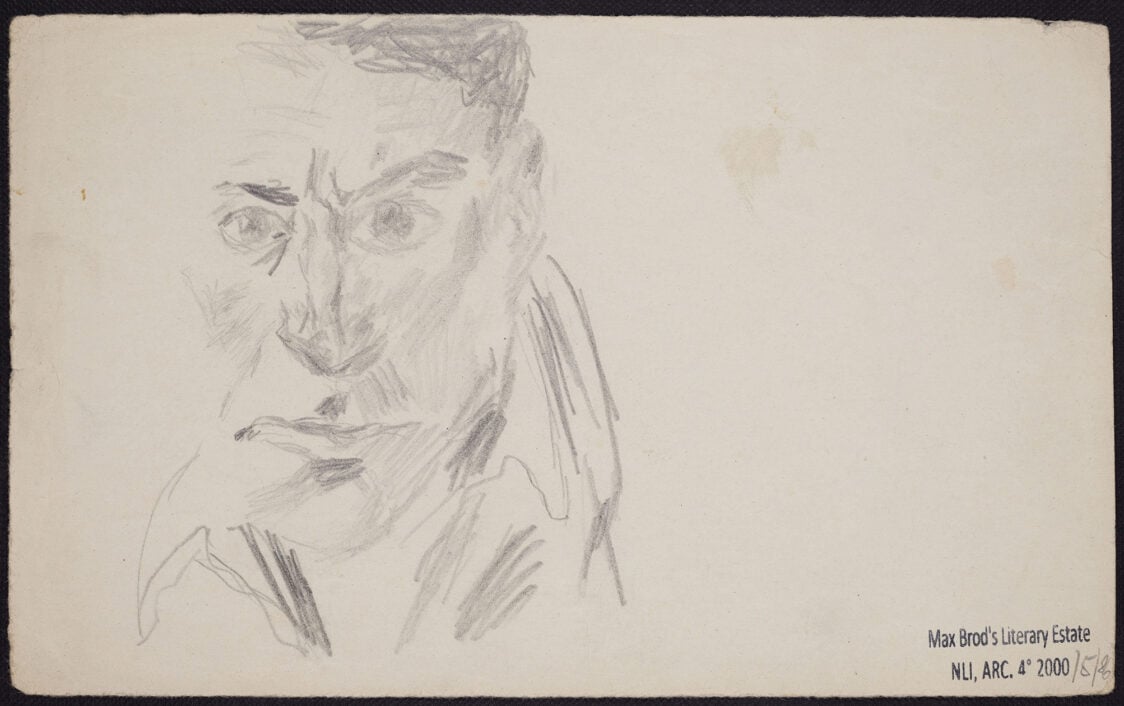

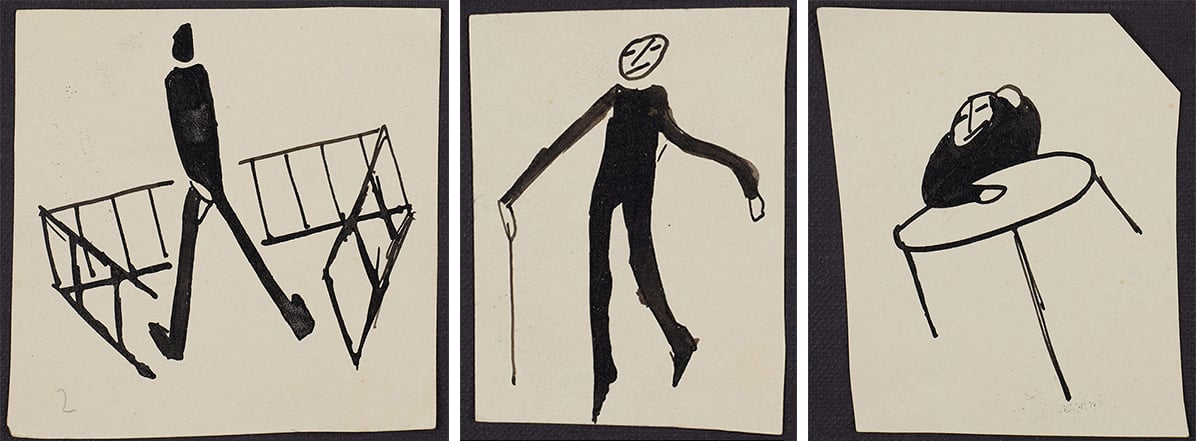

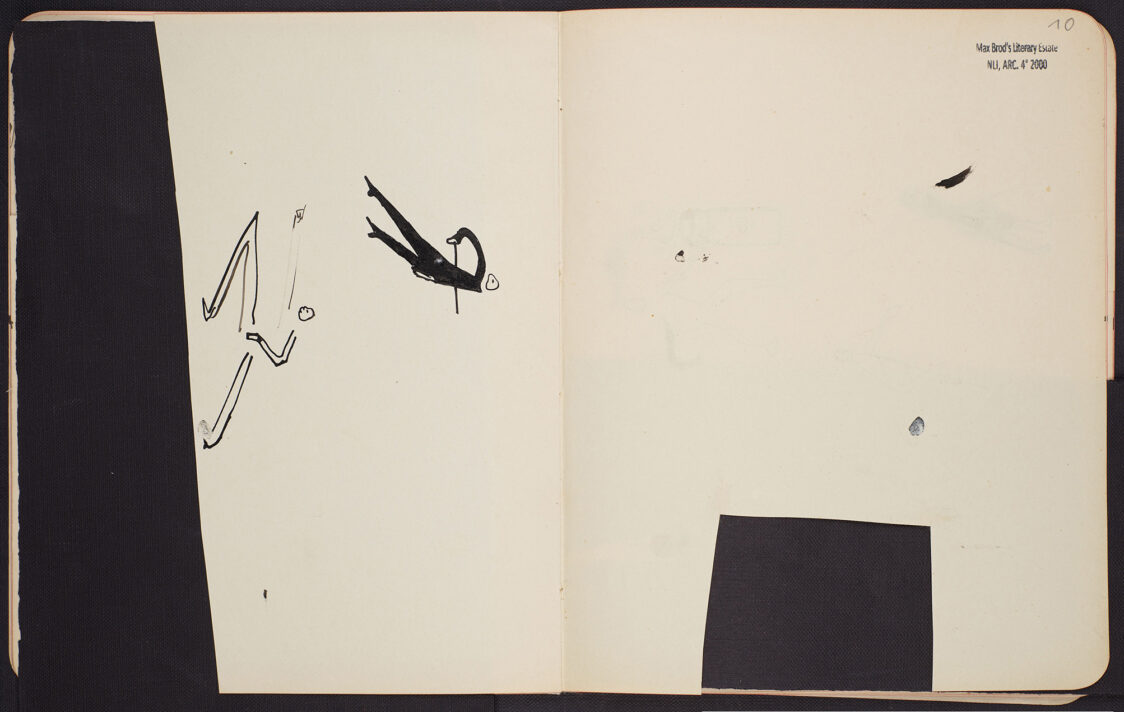

A self-portrait and drawings by Franz Kafka. Courtesy the National Library of Israel, Max Brod Archive

Discussed in this essay:

Selected Stories, by Franz Kafka. Edited and translated by Mark Harman. Belknap Press. 286 pages. $29.95

Franz Kafka was a skinny fellow; he claimed he was the thinnest person he knew. As a young man, he deliberately developed a facial tic. He sometimes felt he didn’t really exist, or if he did, only in the unreality of literature. He enjoyed reading his work aloud, and it’s said he laughed a lot. We have never heard his voice. Accounts of the color of his eyes vary. A dark blue-gray seems the vague consensus. He feared his father, particularly for literary purposes, though he did recount a pleasant memory of going with him to the baths:

When I was a little boy, when I couldn’t yet swim, I used to go sometimes with my father, who also can’t swim, to the place reserved for non-swimmers. Then we used to sit together naked at the buffet, each with a sausage and a pint of beer. . . . Just try and imagine the picture properly—this enormous man, holding a little, nervous bag of bones by the hand.

Later he became a vegetarian, though not at first for ethical reasons. In one of his many, many letters to Felice Bauer, a woman he courted and tortured epistolically for years, he wrote:

I don’t like strict vegetarians all that much, because I too am almost a vegetarian, and see nothing particularly likeable about it, just something natural, and those who are good vegetarians in their hearts, but, for reasons of health, from indifference, or simply because they underrate food as such, eat meat or whatever happens to be on the table, casually, with their left hand, so to speak, these are the ones I like.

He enjoyed his vegetarian status primarily in the evenings, when he insisted on “all kinds of nuts, chestnuts, dates, figs, grapes, almonds, raisins, pumpkins, bananas, apples, pears, oranges”—far more difficult to acquire than butchered meats. He maintained that he was “made of literature” but felt that he had no control over his capacity for writing, that “it comes and goes like a phantom.” He warned Felice that, as one scholar put it, “he will be a faithless husband because night after night he will commit adultery with his writing.” She seemed okay with this, though we can only assume—it seems that Kafka didn’t save her letters. (Why would he want to save her letters?) William H. Gass remarks on this bizarre five-year correspondence: “They continued to play out their engagement in a landscape of fantasy, but it had become a barren courtyard shit upon by filthy flocks of words.”

Kafka admired Flaubert, Dostoevsky, and Kleist. Goethe caused him a “distracted, nowhere usable excitement,” whereas he discovered early on that an interest in Dickens was fatal. Kafka cherished his dreams and recorded them carefully in his diaries. For example:

I dreamed today of a greyhound-like donkey, which was very restrained in its movements. I observed it closely because I was aware of the rarity of the phenomenon, but retained only the memory that its narrow human feet were unappealing to me because of their length and uniformity. I offered it fresh, dark-green cypress bunches . . . it didn’t want them, only sniffed a little at them; but when I left them on a table, it devoured them . . . completely. . . . Later there was talk that this donkey had never before walked on all fours, but had always held itself upright like a human being and had shown its silvery shining breast and its little belly. But this was actually not correct.

He felt that the Day of Judgment was in fact a court-martial. Also that if there were a transmigration of souls, he was not yet on “the lowest rung” of a presumably ascending ladder. He felt that his life was “the hesitation before birth,” and thought often of jumping—through windows and off balconies. When he was thirty-six, he wrote a mean one-hundred-and-three-page letter to his father that he gave his mother to deliver, which she did not. Many readers are more nonplussed than usual when dealing with this “letter.” It’s extreme, exaggerated, loopy, lawyerly, and, in the judgment of a scholar, “symbolic parricide.” Though never sent or received, this “letter” ended up in the possession of Kafka’s friend, Max Brod, who seems to have saved everything, including all the work Kafka instructed him to destroy. He allowed that “The Judgment,” “The Stoker” (even though Kafka admitted it was a sheer imitation of Dickens), “A Country Doctor,” “The Metamorphosis,” “In the Penal Colony,” and “A Hunger Artist” could escape the flames.

Reiner Stach, Kafka’s biographer, says “it appears unlikely that if Kafka were to rise from the dead, he would be able to tell us something that has not already been discussed.” Hundreds of scholars have made the study and parsing of every scrap of Kafka’s life and writings their own life’s work. It is legend; it remains a given that modern literature would scarcely exist were it not for Max Brod and his refusal to deliver such genius writ to oblivion, though he suffers, even in death (he died in 1968), the constant criticism that he messed inordinately with it. He edited, he rearranged, he smoothed and shaped, he purified and sanctified. He strove toward aura, a specific aura, a cloaked, almost comprehensible wisdom. In the eyes of the new critics, the new translators, Brod remains, along with Edwin and Willa Muir—the Scottish couple who first cast Kafka’s work into English—well-intentioned but highly suspect in aim and deeply, interpretively incorrect. Though it could be said that all interpretations of Kafka are incorrect. They are allowed but irrelevant. (Susan Sontag said that interpretation is the revenge of intellect against art.)

It is access to Kafka’s world that is sought and denied, over and over again. The more that is written about Kafka, the more that his images are scrutinized—the cages and buckets and horses, the emperors and doorkeepers—the further that access recedes. The truth he demanded of each sentence he wrote fades, vanishes. Indeed, it was not truth he sought at all; it was, as Walter Benjamin so stunningly argues, truth’s transmissibility. The old transmissibility of truth presented in holy doctrine, tradition, parables, had decayed into near silence. Kafka claimed the whisper, but sought as well a different method of retrieval and comprehension of the lost voice.

So do Kafka’s own weird parables slip beyond the parabolic, preparing us for a message that will never arrive, perhaps because we haven’t the means to receive it, as we have not been truly born. He mused often about the ridiculous demands of such a situation. “To not yet be born and already be forced to roam the streets and speak with people.” The absurdity of it all . . .

Kafka’s imagination proceeded via the strange non-narrative manner of dreams, and he cultivated this, trusted it, pursued it to its ultimate fate. He created his own kabbalah linking his subjective self, with its profoundly innocent depths of being, to the obdurate mechanics of the world’s appearances. The words he employs are simple and sturdy enough but they explode and refract, illuminating and obfuscating at once. For a piece to be successful, for it to be “art,” this linkage between two diametrical ways of knowing must be achieved. He was ecstatic after composing “The Judgment,” a story written in a single night, written “with such coherence, with such a complete opening out of the body and the soul,” that it “developed before me, as if I were advancing over water.” He felt how “everything can be said, how for everything, for the strangest fancies, there waits a great fire in which they perish and rise up again.”

Never again would Kafka be so utterly fulfilled by his work. For an instant, his fears had been allayed and transmuted into myth, into art.

According to Stach, these fears and guilts were all-encompassing. In Kafka: The Decisive Years, the second of his three-part opus, he writes:

With uncontrollable mood swings, obsessive fantasies, devastating daydreams, urges that shot like flames into his consciousness, and peripheral impressions that inundated his sense of identity for hours on end, he knew that he was living outside the realm of normal experience.

Well, perhaps. Yet Kafka’s acquaintances tended not to describe him as particularly peculiar. He was always fastidiously dressed. He had a doctorate in law and worked for years at the Workers’ Accident Insurance Institute in Prague. He traveled frequently with friends and enjoyed Yiddish theater. He’d occasionally holiday at spas and health resorts in the country where nudity was the norm, though it is true that he did not care for nudity.

When I see these stark-naked people moving slowly past among the trees (though they are usually at a distance), I now and then get light, superficial attacks of nausea. Their running doesn’t make things any better. A naked man, a complete stranger to me, just now stopped at my door and asked me in a deliberate and friendly way whether I lived here in my house, something there couldn’t be much doubt of, after all. They come upon you so silently. Suddenly one of them is standing there, you don’t know where he came from. Old men who leap naked over haystacks are no particular delight to me, either.

He balanced the benefits of fresh air and exercise with frequenting Prague nightclubs and brothels, often with Max Brod, but his last documented visit (yes, everything is documented) to a prostitute was in 1922, about two years before his death. There is a marvelous photograph of him with one of his lady friends of the evening, a merry and confident wine-bar waitress, one Juliane Szokoll (known as Hansi). Kafka, bowler hat firmly wedged on head, looks unsettled. A largish dog is between them. In many reproductions of this photo, Hansi has been discreetly removed, leading one to assume that this is an inept (the dog is a shaggy ball of blur) portrait of Dr. Kafka and his pet. But Kafka had no pets. This is not difficult to believe. Though he once considered acquiring a dog, a small grateful loyal one. But there were many drawbacks. They could track dirt into the room. They could fall ill, but even if they were healthy, it was inevitable that they would grow old. “Then . . . one must endure the ordeal of a half-blind animal with weak lungs, nearly immobile with fat, and in this way pay dearly for the joys the dog had once provided.”

He could refer to only one animal as “his”—the tuberculosis that would make a burrow of his body, and would eventually suffocate him.

Even before the illness consumed his attention, he could be considerably self-absorbed. “Sorrows and joys of my relatives bore me to my soul,” he wrote in his diaries. He was the firstborn. Two brothers were born before he was five, but both died in infancy: Georg at fifteen months and Heinrich at six. Kafka makes no mention of these brothers in his surviving writing; their deaths seem to have made no impression on him at all. Though as with all matters Kafka, nothing can be said without qualification—the cellars of his castle are without number, which is why it can be so tempting to read and research him interminably. Here is a vivid and melancholy diary entry written about seven years before his death:

I was standing with my father in the entrance hall of a house; outside it was raining very hard. A man was about to turn hurriedly out of the street into the hall when he noticed my father. That made him stop. “Georg” he said slowly, as if he gradually had to retrieve old memories, and holding out his hand, approached my father from the side.

And, it could be argued, and why not, that Georg and Heinrich, out of their extreme and mostly unalluded to existence, had merged as one—heroically, ethereally—to become the youth in “A Country Doctor,” the boy with the splendid wound, the boy past saving, the one who in Mark Harman’s translation of the story lacks “perspective” on his condition. Still, as a visual, it is the wound that predominates, not the suffering child, a rose-pink wound as big as the palm of a hand, delicately granulated, a wound seething with thick worms wriggling from the interior toward the light.

Even so, one cannot imagine Kafka with brothers. Kafka couldn’t either. Surely, brothers would have resulted in Kafka not being Kafka.

Instead, there were sisters, Elli and Valli, with whom he engaged at fond remove, and Ottla, his favorite. All died in Nazi extermination camps in the early 1940s. Elli and Valli were murdered at Chelmno and Ottla at Auschwitz. Franz, who died in 1924, had no premonition of their fate. His genius was not of the prescient variety. He would never, for example, foresee in his worst nightmares that he would be buried beside (possibly between!) his father and mother in a tidy Prague cemetery.

Kafka wrote three novels: The Man Who Disappeared (Amerika),The Trial, and The Castle. Each was abandoned unfinished and published posthumously. The Trial has an ending, but that is only because he wrote the last chapter immediately after the first, before muddling about in the middle, moving from scenes of broad, smutty humor (those little girls scampering around the painter Titorelli . . . ) to the disturbing perfection of “In the Cathedral,” with its centering pearl of the story of the doorkeeper.

In the midst of writing The Trial, Kafka wrote “In the Penal Colony,” the most terrifying tattoo tale ever. The dreadful inscribing machine and its ungodly purpose are described in meticulous detail—their spectacular efficiency and even more spectacular collapse. This is Kafka at his coldest, his most self-loathing and masochistic. The machine, a complex and gleaming apparatus, has at its governing heart a type of harrow whose murderous but artful needles write upon the condemned’s body a reprimand as final judgment, a “sentence” in both meanings of the word. The story, similar in tone to The Trial’s chapter “The Flogger,” concludes in an unusually artful manner, when the main character of the tale, the “explorer” who comes to an island to witness an execution (which goes very much awry), escapes and prevents the condemned man from leaving with him.

Kafka went where his words led him. He was not immune to the ugly sentence, though some critics have given him a reputation for fluidity, transparency, for conjuring a surface that the eye and mind can glide across as though skating on perfectly luminous ice. Samuel Beckett compared his style to a steamroller—a serene steamroller. The reader can feel like an afterthought, which was no doubt Kafka’s intent. He wasn’t writing for us. The sooner the reader realizes this, the better. His land surveyor (whose services are not required), his clerks and servants, his commandants and priests and lecherous women are, for all their banality and commonality, unrelatable as fellow travelers, while his animals—the courteous ape, earnest dog, frightened mole, and ever-hopeful jackals with their rusted sewing scissors (from the curious story “Jackals and Arabs”)—are no more radically realized than his tearful, timid “sport” or nihilistic Odradek. Kafka’s great theme was the impossibility of the self to live in this world. Primarily his self. We may share in this knowledge as we wish. In his diaries, he wrote:

I don’t believe that there are people whose inner condition is similar to mine, nonetheless I can imagine such people, but that around their head as around mine the secret raven constantly flies, that I cannot even imagine.

The secret raven.

Kafka’s thought unfolded in images—secret raven, swimmers who cannot swim, useless physicians, castle, cage . . . He found his fulfillment of an image in “A Hunger Artist” “tolerable,” which was “the highest grade he bestowed on any of his own texts.” He was said to have wept when reviewing the galleys of this story shortly before his death. In this, the artist, the performer, denies himself life because he simply doesn’t care for what is offered. Having proudly exhibited himself for years as a starving man, he has at last foolishly, unexceptionally expired, and a young panther has been installed in the cage on the circus fairway:

The panther lacked for nothing. Without a second thought the keepers brought it the food that it relished; it did not even seem to miss its freedom; this noble body, supplied almost to bursting with everything needed, seemed also to carry around its freedom, someplace in its teeth; and the joy of life issued from its throat with such a fiery glow that it was not easy for the spectators to hold their ground. But they braced themselves, crowded around the cage, and would not move on.

A young panther, caged yet glowingly alive and content with an unquenchable joy in life and the certitude that it is essentially free, is unimaginable, but this is Kafka’s panther. It serves the needs of Kafka.

He was not blessed with visiting beings providing him with metaphors, like Yeats’s “communicators” did for the Irishman. Mostly he was the dramaturge of his highly personal frozen sea, though sometimes he received ideas from things he read about or actually saw. Such as, it seems, in the peculiarly literal case of “The Hunter Gracchus.”

This intriguing fragment—Kafka actually wrote two versions—concerns a hunter who, pursuing his prey, falls from a precipice in the forest and dies. His death ship (we all have one . . . ) loses its way, “a wrong turn of the wheel, a moment’s absence of mind on the pilot’s part,” and he’s doomed to continued life, sailing aimlessly about on earthly waters in his dilapidated vessel and enduring stupid questions from the people he encounters in harbor towns.

On April 6, 1917, Kafka wrote in his diary:

Today, in the small harbor where besides fishing boats only the 2 passenger steamers that provide sea transport usually stop, there was an unknown bark. A heavy old vessel, relatively low and very round-bellied, soiled, as if utterly inundated with dirty water, which still seemed to be dripping down the yellowish outer wall, the masts incomprehensibly tall, the main mast bent in its upper third, wrinkled, coarse, yellow-brown sailcloths pulled every which way between the wood, patchwork, equal to no gust of wind.

I marveled at it for a long time, waited for someone to show himself on the deck, no one came. A worker sat down beside me on the quay wall. “Whose ship is that?” I asked, “this is the first time I’ve seen it.” “It comes every 2 or 3 years” said the man “and belongs to the hunter Gracchus.”

Kafka used the diaries primarily as notebooks and sketchbooks, though periodically he felt the need to return to a more conventional form, recording a certain actuality of daily experience. Keeping the diaries became “very necessary” to him. Covering almost fifteen years, they are filled with dreams; chunks of narratives; copies of letters sent and not sent; strikingly vivid and cruel physical descriptions; fantasies of being tortured, whips, and knives; complaints about noise; musings on kings, swimmers, and erotic strangers; and over and over, feelings of eternal helplessness and fears about his work:

Wrote a little yesterday and today. . . . Just read the beginning. . . . An only barely breathing fish on a sandbank.

Perpetually the same thought, the longing, the fear.

The weakness of memory, the stupidity!

Suffered much in my thoughts

Complete standstill. Endless torments.

Sheer incapacity

The work waiting is immense.

It is necessary positively to dive under and sink more quickly than what is sinking away in front of you.

The Diaries are a wild ride, and a recent (2022) translation by Ross Benjamin is superb. The book is handsome, the notes extensive, and Benjamin’s crisp preface is thoughtful and sincere. The lone previous English translation appeared in two volumes, one in 1948 by Joseph Kresh, the second in 1949 by Martin Greenberg, the work overseen by Hannah Arendt. Both relied heavily on Max Brod’s edited assemblages, his intercessions, orderings, and omissions. Benjamin’s research has brought the play and peculiarity of Kafka’s “method”—obsessive, cyclic, demanding, open-ended and abruptly terminative at once—into fresh light.

The Diaries don’t make for a more comprehensible or congenial Kafka, but they may explain why the shorter pieces, the troubling non-lessons, are so enduringly fascinating. He found work futile, marriage impossible, and pain of the highest metaphysical value. The shuddering glimpse was his forte—a sight pursued until it was close to being an insight, though not quite, never quite.

Kafka cherished his notebooks and tended to them frankly, even innocently. Because the entries leap about so naturally and confoundedly, his interests seem particularly uncorralled by form or even concept. For instance, a discourse on Czech literature or a boring meeting on Zionism is followed by his reaction to a murder:

Sobbed over the report on the trial of a 23-yr.-old Marie Abraham, who because of destitution and hunger strangled her almost 9-month-old baby Barbara with a men’s tie, which served her as a garter and which she untied. Quite schematic story.

This variety gives Benjamin a certain freedom of approach to the material, and grants permission to the reader to graze and enjoy in a way that the more iconic texts can’t offer.

Kafka broke off work on The Castle in 1922 after a mere nine months. That same year, he stopped writing in his diaries. “More and more anxious while writing. It is understandable,” was one of his last entries. Still, he started writing the plaintively obsessive “The Burrow” the following year, and only months before his death in 1924, the fantastic, scrupulously aware “Josephine the Singer.”

These last works have mostly avoided the translators’ scrutiny. It is The Castle—Kafka’s acknowledged classic, which breaks off in mid-sentence—that fascinates and maddens them most. If Nietzsche says that there are no facts, only interpretations, and Sontag agrees, Cynthia Ozick can (and does) say that “translations are indistinguishable from opinions.” But this is anathema to the usual approach of Kafka’s translators. Interpretation must be avoided at all cost. At the same time, every word, every sentence is to be subjected to the most hygienic, scholarly, linguistic, and biographical scrutiny. In such a vise, translators go to great lengths to sound different from other translators, resulting quite possibly in not sounding like the elusive Kafka at all.

I grew up with the translation by the pioneering Muirs, whom I always think of as small saintly devoted creatures, eyes burning, hearts straining, wearing heavy coats against the cold, their fingers made clumsy by mittens, laboring over the curious text by candlelight. They end The Castle so: “I am getting a new dress to-morrow, perhaps I shall send for you.” Disappointing. But in an appendix under the title “Continuation of the Manuscript,” they did include this truncated sentence:

She held out a tremulous hand to K. and made him sit down beside her, she spoke with an effort, it was difficult to understand her, but what she said,

Along with “Another Version”:

“I’ve remembered what my mother once said: ‘This man shouldn’t be let go to the dogs.’ ” “A good saying. That’s the very reason why I’m not coming to you.”

Not that fabulous either. This is followed by “Another Version of the Opening Paragraphs,” “Fragments,” “Two Additional Pages Included in the Text of the Definitive German Edition,” and “The Passages Deleted by the Author,” which includes such lines as: “lay then, almost undressed, for each of them had torn open the other’s clothes with hands and teeth, in the little puddles of beer.”

To the reader, these lines may seem neither more nor less relevant than the undeleted ones—much in the way that Kafka wrote that “the correct understanding of a matter and misunderstanding the matter are not mutually exclusive.” But to the professional student of Kafka, the aspiring professional student of Kafka, they are to be scrutinized cautiously and reverently—their concealed import, if revealed, might shake the very foundation of being. You never know.

J. M. Coetzee writes that the Muirs’ translation, of The Castle in particular, includes “scores, perhaps hundreds of errors of detail which, while they may not be important individually, have a cumulative effect, putting readers on an insecure footing.” He is referring to a lack of trust in the translation, of course, as the whole purpose of reading Kafka is to realize one’s “insecure footing” in the world. We are all like his tree trunks in the snow.

Coetzee spoke of the Muirs in his review of Mark Harman’s 1998 translation of The Castle. He approved of Harman’s labors in general, though he does have some criticisms, which include overtranslating, too great a fidelity to Kafka’s German word order, a tendency to fall into “mindless late-twentieth-century jargon,” unnecessary colloquialisms, and “odd moments of inattention.” He assures us that these faults are not terribly important. The larger problem, in his view, is when Harman, like his predecessors, is faced with patches of bad prose, original bad prose, which Kafka was not incapable of producing. The Muirs solved the slovenly-writing dilemma by being good householders and tidying sentences as one would a room, but what is the modern translator to do? Should reverence serve carelessness, even incoherence? Or should the text be altered ever so slightly, ever so surgically, for clarity and depth—thus reprising the blasphemies of Max Brod?

Coetzee concludes that the problem is “finally intractable.”

For his part, Harman chooses allegiance to sentences so ungraceful that Kafka, as Coetzee suggests, might have written them in his sleep. For example, Harman ends The Castle with a more exact rendering of the first of the Muirs’ “Continuation of the Manuscript”:

She held out her trembling hand to K. and had him sit down beside her, she spoke with great difficulty, it was difficult to understand her, but what she said

Bumpy.

Kafka’s hitherto famous purity of style is currently taking a beating. More in fashion is the exposure of his influences, his hesitations, and his substitutions in the process of composition. It is quite possible that we will never see the end of new and newer translations of Kafka, each one building upon the one before, denying, modifying, expanding, taking us further and further from Kafka’s great original quest for transmissibility. We are far from the days when an eminence like Thomas Mann—indeed it was Thomas Mann—could praise him as a religious humorist, a reverent satirist, and a warmhearted fantasist. The new critics and translators tumble about in the bouncy house of endlessly unnecessary possibilities. Kafka kicked literature off the path—the path of knowledge, of becoming, of being. Some translators, like Susan Bernofsky, appreciate that he got the joke, though sometimes he was too tortured by life to appreciate it as a joke. Others, like Mark Harman, favor a more contextual approach, reveling in double meanings and “verbal leitmotifs,” even arguing that a “case can be made” for seeing the thrown apple that lodges on poor Gregor Samsa’s insect back as “an allusion to the expulsion from paradise, a biblical story which greatly preoccupied Kafka.”

This is pretty daring. The Bible? Gregor’s musty, stuffy family home as Paradise? But this is nothing compared with Harman’s brash, even brassy, decision to change (in a new edition of Selected Stories published by Belknap Press) the title of Kafka’s—in his own words—“exceptionally repulsive,” “infinitely repulsive” bug story from “The Metamorphosis” to “The Transformation.”

“Die Verwandlung,” the German title, is closer in meaning to transformation, and Harman argues that Kafka, because he was aware of Ovid, could have called the story “Die Metamorphose” but did not. Transformation sounds more contemporary and less magical and sudden, but oddly its meaning is more fundamentally spiritual. This would seem at odds with Harman’s intended approach. Still, this is his gesture, his leap from the herd, and he’s sticking with it. Acceptance might not come easily, I think. It’s one thing to refer to the novel Amerika as The Man Who Disappeared because no one cares, but to attempt to rattle on about the Czech-German-Jewish author Franz Kafka and his seminal work “The Transformation” might get you thrown out of the spaceship.

Other choices made in Harman’s Selected Stories are unrevolutionary but puzzling. Several stories that deserve investigation are omitted, as well as most of the shorter pieces, with their dazzling flash: “The Vulture,” “The Top,” “Eleven Sons,” “The Test,” “The Departure,” “Children on a Country Road,” etc. Among those that are included, “Poseidon” and “Little Fable” are mundane, while the uncomfortable charm of “A Crossbreed” is erased by too-literal editing and the addition of a reference to a folktale about a champion rat-catching cat that Kafka alluded to in his diaries.

A more satisfying collection is the Schocken Kafka Library edition of The Complete Stories, originally published in 1971, with translations primarily by . . . the Muirs.

A translator thinks in terms of “solutions”—a cage in search of a bird—whereas Kafka most certainly did not. He lived in the labyrinth, the cageless prison, the echo chamber, the endless rooms of dreams. He belongs to none of us—Jew, Christian, Muslim, certainly not the timid middling unbeliever—yet in him we have everything we need and more than we deserve. His enchantments are real, even punishing; they cannot easily be dismissed. All edifications, criticism, and conclusions cannot keep us from his strange spell. So it is that we must approach his work again and again with, in George Steiner’s phrase, “a freshness of encounter,” and we must allow no subalterns to stand in our way.