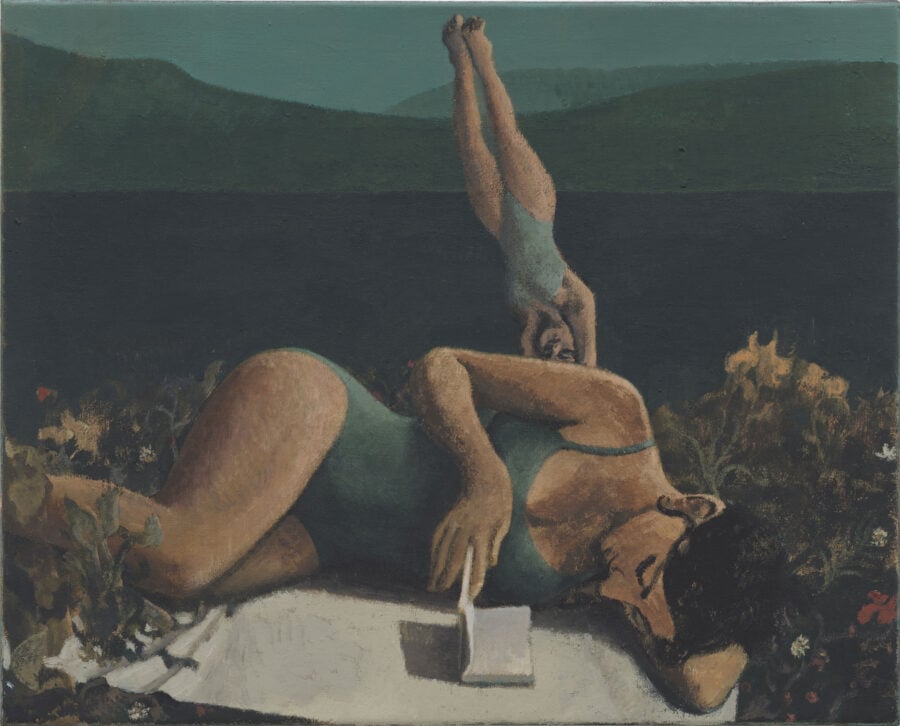

Beach Couple V, by Lenz Geerk © The artist. Courtesy the artist and Roberts Projects, Los Angeles

New Books

Something about poetry—writing it, reading it, writing about reading it—begs to be postponed indefinitely. I don’t mean that I dread it, only that it calls for conditions that never quite arise. My future, I imagine, needs poems more than my present does, because my future contains a more poetical me, someone attuned, observant, virtuous, vulnerable; or else someone ravaged and lusterless, inscrutable to himself, in need of spiritual realignment. I assume my life will improve or deteriorate dramatically, and in either case I’ll be ready for poetry. Part of the problem is that poems are held to be lapidary,…