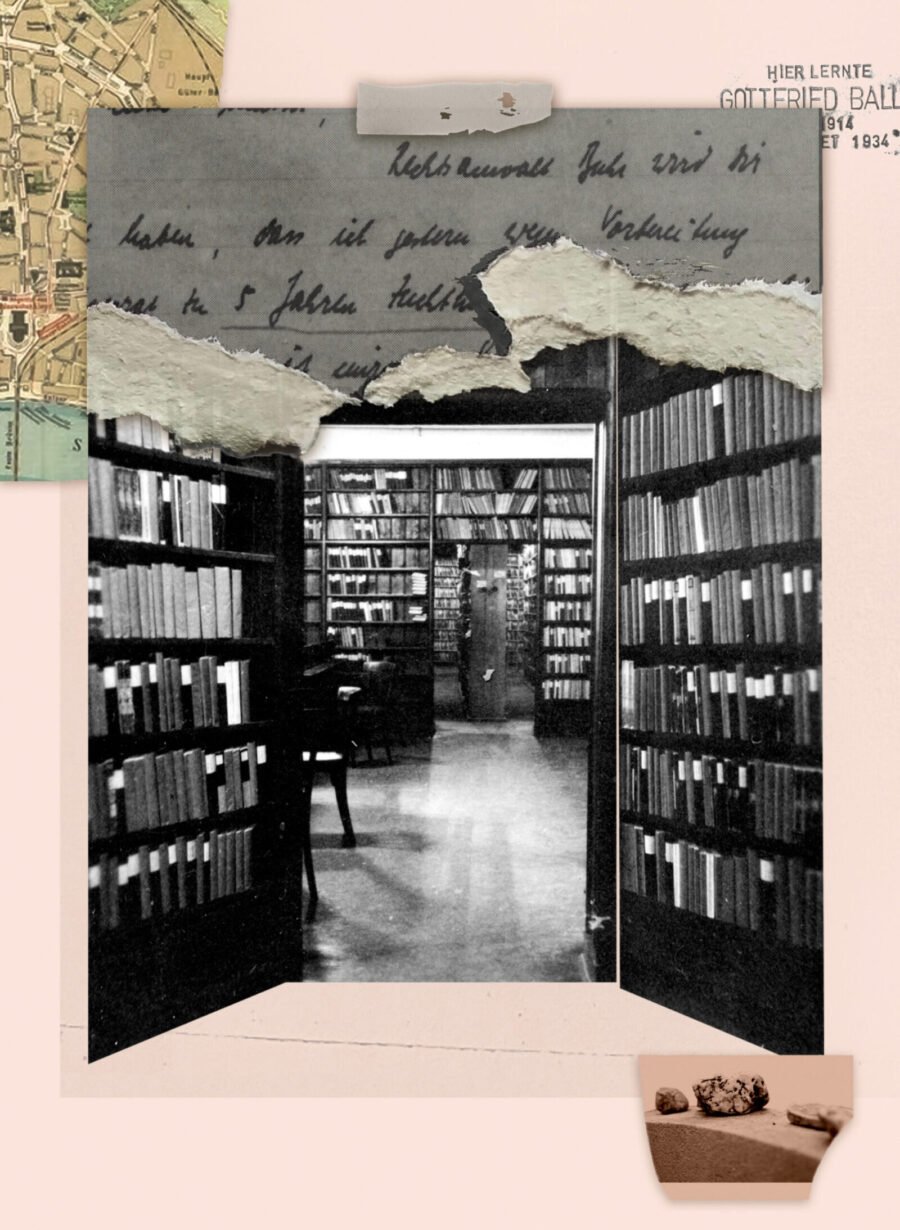

Collages by Jen Renninger. Source images: Detail of a letter by Gottfried Ballin and his Stolperstein. Photograph of the lending library at Lengfeld’sche Buchhandlung. Courtesy the author. Detail of a photograph of a rock atop a gravestone at the Jewish cemetery in Cologne © Federico Gambarini/picture alliance/Getty Images

By chance, I arrived at the Jewish cemetery in Cologne on Yom Kippur. It was late September last year. I’d not fasted; I never do. That morning’s meal at the hotel had included soft-boiled eggs, buttered toast, pastries, jam, rolls, liverwurst, and a little pyramid of pork sausages; I shouldn’t have been surprised to find the gates locked shut to me.

I was there to visit the graves of my great-great-grandparents Alexander and Clara Ganz. Through the iron bars, I could see glades of beeches and oaks, rows of old headstones overgrown with moss and ivy. Above the doors of a stucco mourning hall was a Hebrew inscription that I couldn’t read. I’d later learn that it came from the book of the prophet Habakkuk: “The righteous lives in his faith.”

Coming to Cologne had been a last-minute decision. I was in Europe on vacation after finishing writing a book, and I had a few days to kill between a trip to Marseille and meeting friends in Paris. I’d been meaning to visit the city for some time. In 2020, before the pandemic hit, I’d been supposed to attend the launch of a book about my German ancestors, the Ganz family, and their onetime ownership of a famous bookstore, Lengfeld’sche Buchhandlung, the oldest in Cologne. Until a few years ago, the shop, which first opened in 1842, still bore the name M. Lengfeld’sche Buchhandlung A. Ganz Nachf., signifying that the original proprietor, an M. Lengfeld, had been succeeded in ownership by my great-great-grandfather Alexander Ganz.

The next day I took the tram from the center of the city back out to the cemetery to try again before I had to catch my train. I didn’t know where Alex’s and Clara’s graves were, but I had given myself two hours. The place had been inaugurated just after the First World War, but the state of gentle disrepair gave the impression of far more archaic origins. A much older Jewish cemetery could be found across the Rhine in Deutz: Jews had been expelled from Cologne in 1424—for eternity, the city proclaimed—and would return only in the wake of the French Revolution and the new Republic’s annexation of the left bank of the Rhine.

For about an hour, I wandered up and down the rows. It wasn’t the first time in Cologne I’d felt a little like a ghost, and it wouldn’t be the last. Manheimer, Frenkel, Briefel, Szczawinski, Felber . . . no Ganz. Back at the gate, I tried one of the buzzers. It rang several times, and an irate German voice answered. “Ja, bitte?” After some explanation, the voice softened, and told me where to look.

The two stones were crooked and leaning into each other. alexander ganz, geb. 1851, gest. marz 1923. The exact dates of his birth and death were no longer legible. clara ganz, geb. 20 september 1850, gest. 14 oktober 1925. I gazed at them a while. What else are you supposed to do? I placed a small rock on top of one, as is traditional. I felt a strange sense of pressure: there was a tender but insistent demand here, something being asked of me, mutely. I began to step away and then immediately came back. I started to sob. I was moved, but I was also frustrated that I couldn’t understand. I even said aloud, “What? What should I do?”

A few years ago, I applied for German citizenship restoration, a right for those whose ancestors were denaturalized by the Nazis. I’d decided to do it after learning about a certain employee of our family bookstore: Gottfried Ballin. In 2018, I was talking to a professor of mine from college, who asked if I had lost any family in the Holocaust. “No, we all made it out,” was the answer I was used to giving. For my immediate family this was true enough. But she entered the family name into a database of Stolpersteine, engraved brass cobblestones that commemorate victims of the Nazis—metaphorical “stumbling blocks,” placed into the ground, usually in front of where the victims had lived or worked. She found Stolpersteine in Cologne for Gottfried and his mother, Anna Ballin, née Ganz—the eldest child of my great-great-grandparents Alex and Clara. Gottfried would have been my grandfather Peter’s first cousin.

The inscription on Anna’s Stolperstein said that she was born in 1881, deported to the Łódź ghetto in 1941, and that she’d died on August 29, 1942. Gottfried’s was longer. It said that he was born in 1914, and verhaftet, arrested, in 1934. The next year, he was convicted of “preparing for high treason,” and sent to a prison called Herford, just outside the city. Another prison, Dortmund, was listed along with the year 1939, and then Oranienburg, a concentration camp, alongside 1940. He was murdered, the stone read—ermordet—at Auschwitz on March 4, 1943.

My grandfather had never mentioned Gottfried, or Anna, who was his aunt, not even in the memoir he’d dictated to my sister in the Nineties. It turned out that the two were named in my great-grandmother Resi’s memoirs, but no one in my family had seemed to notice: Resi writes that Gottfried was deported to a concentration camp, and that he was shot (the latter is likely untrue). No mention is made of Auschwitz or Gottfried’s arrest for treason.

Since childhood, I’d been obsessed with the Nazis and the war, particularly with the romantic image of the underground, partisans, maquisards, saboteurs. My grandfather Peter, who ended up in Paris in the late 1930s, had joined the French Foreign Legion, but France fell before his unit saw any combat, and under Vichy, his regiment was sent to North Africa and then turned into a labor detail. My grandfather on my mother’s side, Maurice Arditty, born in the United States, was a gunner on bombers in the China–Burma–India theater, but that was against the Japanese, not the Nazis. Gottfried was something else: a Resistance fighter, in my family. This was the sort of person I hoped I would’ve been, if I had been there.

I asked my father why Peter had never mentioned Gottfried. After all, they were almost peers: Gottfried was only two years older, and both lived in Cologne until the early Thirties. Peter surely would’ve seen a lot of Gottfried around the bookstore; Felix, Peter’s father, had become a co-owner in 1913. But my dad was not carried up in the sudden interest in all things Gottfried that swept my mother, my two sisters, and me. It even made him a little sulky. “He wasn’t even a blood relative.” “Yes he was, too!” “Well, maybe Pop just didn’t like him.” Possible. Pop Peter, as we called him, was a businessman: pragmatic, unsentimental, and very judgmental. He liked to give single-word assessments of people: “Fat.” “Smart.” “Stupid.” From 1942 to 1945, he’d been in Havana, and he’d worked at a bookstore, knowing the trade a little. Hemingway was a customer. “What was Hemingway like, Pop?” “He smelled.” Peter’s favorite expression was “bullshit.” In his thick German accent it sounded more like “booolshit.” He was vaguely leftish in his sympathies, but he didn’t care for self-righteous idealists. “I think Harry Truman was a good president,” was one of the only political statements I ever heard him make.

It was still strange to me, though, that Gottfried and Anna had been passed over in silence. Family pride is a congenital vice for us. While my parents balanced out bigheadedness in the individual children with regular doses of self-doubt-inducing critique, the family as a whole was excepted from the strictures of modesty. The fact that we owned a bookstore was given practically legendary status. As was the supposedly ingenious “ski corset” invented by my great-grandmother’s family, the Lobbenbergs: an especially comfortable corset with whalebone stays curved in the manner of skis. I knew that my great-grandfather Felix had played chess and boozed with the artist Max Ernst, a customer at the store, and that the family’s Skye terrier, Yanko van Upstalsboom, once barked at Thomas Mann at the beach. I was so drilled in rattling off such facts that it got me mildly and justifiably bullied in elementary school. I didn’t know the Yiddish term yet, but we were Yekkes: pretentious German Jews. So was there something shameful about Gottfried that he wasn’t part of our litany of brushes with fame and culture? Why was his story not one of the most venerated Ganz anecdotes? Maybe the cause was simply pain, or survivor’s guilt. I’d seen my grandfather express the latter once, when I was a child. He was at the dinner table, after a few too many Johnnie Walker Blacks. The topic had come around to the war years, specifically his family’s escape from Germany. He kept on saying, “We got away with murder. We got away with murder.”

Beginning with a translation of the German Wikipedia article on Gottfried Ballin and branching outward, I learned that he had been a member of the Socialist Workers’ Party of Germany (the SAPD), a Marxist group that broke away from the Social Democratic Party (the SPD), in 1931, believing that the SPD was too timid in the face of fascism and that only a united front of Social Democrats and Communists could defeat the National Socialists. That all sounds nice, but their group was too small—only about twenty-five thousand members at its peak—to effect such an entente. In the last two free elections in Weimar Germany, when the party sought office, it failed to win even a single seat in the Reichstag. Exactly the kind of principled, decent, but ultimately ineffectual and even doomed left-wing politics I’d always been attracted to: my kind of bullshit.

After the Nazi seizure of power in 1933, the SAPD went underground. Gottfried was recruited into one of its cells by Erich Sander, the son of the famous photographer August Sander. The group met secretly in an old guard tower near Rösrath, a town just east of Cologne. Gottfried was responsible for collecting dues and distributing a party magazine, The Banner of Revolutionary Unity, which was produced across the border in Belgium and smuggled into Germany rolled into the tubes of bicycle tires. In 1933, the Ballin house was graffitied with the words jewish pig; soon after, SS men ransacked the home looking for evidence of treason, tearing apart the cupboards and ripping up the floorboards. When they came across a box of Gottfried’s father’s war decorations, they saluted and left. But in September 1934, the Gestapo captured the entire SAPD network. Gottfried was sick in bed with paratyphoid fever when they got him. He was sentenced to five years in prison, and set to be released in September 1939, but the war broke out that same month, and he was instead transferred to the Sachsenhausen concentration camp in Oranienburg, near Berlin. It seems to have been sometime in the fall of 1942 that he was deported to Auschwitz.

As I learned all this, I was eager to tell one of my close friends. His grandparents had survived Auschwitz, and I felt that this new knowledge would give me more credibility as a Jew in his eyes: my family, too, had suffered, perished. “You see,” he responded, “this is why we have Israel.” I was extremely angry. He knew my feelings about Israel had always ranged from ambivalent to staunchly opposed. Those were not Gottfried’s politics, I said, that’s not what he died for: he was a socialist, and therefore an internationalist. I didn’t want his memory to serve as an object lesson for that oppressive, nationalist project. I think, in my high dudgeon, I even uttered the words, “How dare you?”

My dad also got into a high dudgeon. Some years before, when we’d learned that the bookshop, Lengfeld’s, still existed, he grew suddenly wrathful. “I want to know how they got our fucking bookstore,” he bellowed, storming from the kitchen to the bedroom, iPad tucked underarm. He tapped out an email that I remembered as betraying his fury, but was in fact pretty nice. He explained that a store by the same name had been owned by his great-grandfather Alexander, and then by his grandfather Felix, who left Cologne with his family in 1934. “I do not know whether he sold the business prior to their departure. I was curious how you came by the name for your business.” He got no answer. A couple of years later, I noticed that the “A. Ganz” part of the name no longer appeared in online listings. I wrote an exceedingly polite message to the store, hoping to assuage any fears. Referring to my father’s email, I said that we had simply been excited to learn that the shop still existed and to make contact; we had no intention of making any claim on the business. “We know now that my great-grandfather Felix sold the bookstore fair and square,” I said. However, being lovers of books ourselves, we were very proud to have once owned such a beautiful institution. “I think I can speak for my entire family when I say it meant a lot to us that the name was still somehow associated with both the store and the city of Cologne.” I added that I was in the process of recovering my German citizenship and that I hoped to visit soon. I also offered to scan and send photographs we had of the shop, taken in the 1930s.

Over a year, no answer came. According to the German business registry, the store’s name was officially changed in 2020. “It’s because Dad wrote that email,” my mom said later, as we all gathered in the living room. (Lengfeld’s denies this.) “I don’t know why I did it . . . I don’t want a bookstore. I should’ve just left them alone,” my dad said, grinning sheepishly. “ . . . Aggressive Jew.”

“Fair and square” may have been an overstatement. In April 1933, the Nazi storm troopers, the SA, began a campaign of vandalism and intimidation targeting Jewish businesses across Germany. Resi’s memoir recounts a day in this period: Felix and Max Pinette—his brother-in-law and business partner, known as Pino—had, she writes,

spent the day in the shop to be at hand should windows be broken . . . When Felix came home in the evening his face was not white but gray with horror, and from that moment onwards he did not think Germany, “a fit country for his children to grow up in.”

Throughout the country, the SA men posted signs reading: geh nach palästina—go to palestine. To encourage rapid emigration, the Nazis and Zionist agencies had negotiated an agreement whereby German Jews would be allowed to transfer some of their assets in the form of German export goods. When Felix left Cologne with his family in 1934, he sold his share of the bookstore to Pino. Two years later, under the Nazi policy of Aryanization, Pino was forced to relinquish the store and passed it to longtime employees Hans Schmitt and Sophie Lutze, who were non-Jews. According to Resi, Lutze said, “We will keep the door wide open for you.” No one ever tried to go back for it.

I soon learned that Gottfried had been able to write and send letters during his time in prison and at Sachsenhausen. A collection of the letters had been published by the same independent Holocaust researchers who would later write the book about the Ganzes and Lengfeld’s bookstore, Fritz and Brigitte Bilz, an elderly married couple. The two were part of the History Workshop movement, a radical school of historiography that had taken root in Germany in the early 1980s and contributed to the rise of the Historikerstreit, or Historians’ Dispute, when right- and left-wing intellectuals battled over the proper place of the Holocaust and Nazism in German history. The movement focused on what was called “history from below”—the forgotten stories of common people.

The title of the collection of Gottfried’s letters, Diesen Menschen hat man mir totgeschlagen, translated literally to something like “They beat this man to death for me.” It sounded like a confession of some oblique guilt and made me uncomfortable. But a translator explained that the words—spoken by Gottfried’s fiancée, Helene Sälzer—meant something closer to “They took him from my life.” On the volume’s cover was a photograph of Gottfried. He wore round glasses, a little like mine, and his grave demeanor was half broken by a slight ironical look, almost a smirk. His hair was clearly curly or at least very wavy, but had been tamed by the heavy use of a comb and pomade.

It turned out that my family also had a photo of Gottfried. He was there in a partially blurred picture of the bookstore’s employees, taken in the early Thirties. Most of the clerks looked almost Victorian—or, I suppose, Wilhelmine—in their starched white collars and three-piece suits. But Gottfried, in the back row, wore a striped shirt and a checked jacket, his tie and collar slightly askew. He was in sharp focus, looking directly at the camera—the cinematic hero. His expression was again lightly sardonic: a Jewish wiseass, a natural resister and conspirator, one maybe even handicapped in that role by looking too much the part.

Most of Gottfried’s letters were addressed to his mother, Anna, and to Helene. Helene, whose petite stature and short hair earned her the nickname der Jung, the boy, was the daughter of a Social Democratic metalworker. She and Gottfried had met after an SAPD meeting in Kalk, a suburb of Cologne; Helene was without a place to stay, and Gottfried brought her to his home nearby. She would soon move in, living with Gottfried, Anna, and Gottfried’s two brothers, Arnold and Wolfgang.

Source images: Detail of a letter by Gottfried Ballin and a photograph of employees at Lengfeld’s. Courtesy the author

Anna Ballin was something of a bohemian. She had been a suffragette and, even before the First World War, wore “reformed” clothes rather than corsets and high-necked dresses. Her husband, Martin Ballin, a doctor, returned from the war with an Iron Cross First Class and also, in Resi’s words, “severe nervous weakness.” He killed himself in 1920. Anna raised the boys and pursued a creative life. She’d studied art, and her paintings and drawings had come in for critique by the Ganzes, who judged that she was not a genius. Now she painted her piano pink, shortened the legs of the dining-room table. Her last letter to her brother Karl Justus’s family, who had fled to France, contained a message to her niece: “Tell Beate that it is not so important to become a great, well-known artist. What matters is turning your life into a work of art.”

The high-speed rail that leads from Paris through Belgium to Aachen and then on to Cologne runs along the path of the first international railway in Germany, built in 1843, just a year after Lengfeld’s opened. On my first trip to the city, I arrived at the Hauptbahnhof—the central station—at night. The glass-and-steel roof soared above the platforms, and the interior gable was illuminated by a giant neon advertisement for 4711 Echt Kölnisch Wasser, the original eau de cologne, a scent dating to the late eighteenth century and the source of the city’s association with fragrance. Just outside the station, the massive cathedral known simply as the Dom, the largest Gothic church in Northern Europe, rose like a great fang from the city. After surviving relentless Allied bombing, it had become a symbol of miraculous hope. A hundred years earlier, to the poet Heinrich Heine, born a Jew in the Rhineland, it had represented medieval backwardness: he described it as a “spiritual bastille” designed to lock up reason forever.

The next day I set out to find Gottfried’s and Anna’s Stolpersteine. Gottfried has two: one outside his secondary school and one on Steinfelder Gaße in the center of the city, the location of his last residence in Cologne. Anna’s Stolperstein was supposed to be on Maastrichter Straße in the Belgian Quarter, outside a former Judenhaus, where she was forced to live, beginning in 1941, along with other of the city’s remaining Jews, until her deportation to Łódź. There was now a sidewalk café at the address, and I searched up and down the street, wondering if the stone was hidden under one of the bistro tables. On my phone I pulled up a picture of the Stolpersteine associated with the spot—there were five—and found them nestled against the building, concealed by a low bench stacked with ashtrays. I asked the young waitress setting up if I could move it to take a photograph; this was one of my relatives. She was unfazed, breezy: “Sure, of course.”

My next stop was Lengfeld’sche Buchhandlung. I’d managed to make contact. I had written to the store again, even more formally this time and with no reference to their prior inattention, saying that I’d learned of Gottfried and his connection to the store. I wondered if it would be possible to arrange a reading in his honor one evening. “His letters were published and I thought maybe reading some parts of Goethe’s Egmont would be fitting, too.” They’d answered briefly but with appropriate exclamations, writing that they were quite busy with the Christmas season but excited to be in touch, and that they’d send a “decent reply” soon.

Christmas came and went with no further response, but I’d developed a friendly rapport with whoever was on the other side of the store’s Instagram account, someone seemingly younger. I told her—I think it was a woman—that I’d be dropping by. At its height before the war, Lengfeld’s boasted eight storefront windows, three floors of wares, and a large lending library in the basement. The interior was designed by the architect Albrecht Döring and decorated with works by the expressionists Carlo Mense and Emil Schumacher. During the first “thousand-bomber raid,” in May 1942, a massive assault on Cologne by the Royal Air Force, a bomb penetrated the building’s subbasement and destroyed almost the entire stock. Hans Schmitt, one of the employees who had taken over the store, saved what he could and kept the business going out of his apartment. Today Lengfeld’s is housed in two small adjoining storefronts on Kolpingplatz, a small square opposite a Gothic church. I stepped inside and walked up to the counter. “Hello, my name is John Ganz,” I announced. “My family used to own this store.”

I was greeted with stiff courtesy—this was characteristically German, of course, but it was also a bit more. I was ushered into the next storefront to meet the most senior staff member, Hildegund Laaff. She was very elderly, and seemed to have a slight tremor. She didn’t speak English, and our exchanges had to be translated by the clerks, whose English also was not the usual near-perfection one can expect from younger Germans. The floor was lined with Persian rugs, and the walls, above the books, with photographs of literary luminaries. The shelves and display cases were dotted with an adorable green owl—the store’s mascot since before the war, I gathered. My grandparents’ apartment had been full of owl tchotchkes; now I wondered if this had been in honor of Lengfeld’s. I wanted to buy something, but since I can barely read any German, a book felt silly. By the register were notebooks made to look like classic book covers designed by the German publisher Suhrkamp Verlag—stark, with serif text. I grabbed one without thinking; it was modeled on Christa Wolf’s novella Was bleibt (What Remains). I reached into my pocket for some euros, but they said, “No, no, please. That is for you.” I felt awkward, but didn’t insist. The clerk gave me a business card and some brochures. Behind the counter I could see oversize pieces of card paper printed with three owls in a tidy row. This was what I really wanted. He reached for the pile to add one to my bag and then seemed to change his mind.

Later, I met a German friend for a beer at an Italian bar. He told me about a recent scandal out of Berlin. A prominent and very pugilistic left-wing writer, an outspoken critic of Israel, had for years—as long as he’d been in the public eye—claimed to be Jewish, and this had turned out to be false. Some had accused him of fraud. Two Morettis in, I nearly howled with laughter—a Kostümjude, they were calling him. My friend didn’t think it was funny.

When we finished our beers, he said he wanted to show me something. Around the corner from the bar was a building called Gottfried Ballin Haus. It had a gold plaque engraved with Gottfried’s image but didn’t seem to claim that Gottfried had any connection to the place.

I returned the next day and rang the bell. A very suspicious woman answered.

“Hi, this is my relative,” I said, pointing. “I’d just like to know how this building came to be named after him?”

“I cannot give you any information about this.”

I pointed again at the plaque by the door. “No, you see, this is my cousin.”

It went back and forth like this a couple more times until a young man behind the desk realized what was going on and invited me inside to sit. He said he was the son of the owner. His father had named the building for Gottfried as a way of proclaiming his anti-Nazi politics; Gottfried was apparently a well-enough-known figure to be used to make such a statement. “It is really incredible that we are sitting here and chatting about this now,” he said. Then he launched into his theory of Nazism. He said what a shame it was that Buchenwald was so close to Goethe’s city of Weimar, how they had spoiled this idyll. He suggested that the Nazis in essence were not really German at all, that they represented the imposition of an alien Roman culture. A strangely völkisch type of anti-Nazism, I thought to myself, listening politely. But it was not all that different from what I’d heard from my ancient great-great-aunts on the Upper West Side: “We had the best poetry, the best philosophy, the best music. How could it happen?”

The next day was my last in the city. Fritz Bilz had offered to meet me at the NS-Dokumentationszentrum—a research institute and museum of the Nazi regime—but I decided I’d had enough of Germany and wrote that I had to leave. Before catching my train, on my way back from the cemetery, I walked past Lengfeld’s again. I stood outside, across the small square, and looked at it for a little while. A young woman saw me, started to come out, and then stopped at the door. Maybe it was my friend from Instagram. I turned around and quickly walked away.

In Gottfried’s letters, there were hints of tension between the Ganzes and Ballins. Gottfried was “the only family member who was politically active,” the Bilzes wrote in their introduction, and he had “accused his family of a bourgeois lifestyle and carelessness.”

The Ganzes were part of the Bildungsbürgertum, the educated bourgeoisie. Bildung, connoting the constant cultivation of an individual’s ethical and aesthetic personhood, was the central ideal of the German Enlightenment, with spokesmen in Goethe, Schiller, Humboldt, and Lessing. German Jews, who were emancipated at the tail end of the Enlightenment period and throughout the Romantic era, took to Bildung almost as a new faith, or the natural development of the old one. In the words of the historian George L. Mosse, “The concept of Bildung became for many Jews synonymous with their Jewishness.”

Prior to emancipation, Jews were restricted to a few narrowly prescribed roles—peddler, printer, moneylender—but now educated Jews became prized and even envied by the Aufklärer, the “enlighteners”: they were considered to be particularly unprejudiced and clear-sighted. That the Jews had attained culture after ghettoization, and despite religious backwardness, was taken as a sign that all of humanity might be improved. In 1779, Lessing’s play Nathan the Wise portrayed the eponymous Jewish merchant as the embodiment of Enlightenment values: noble, open-minded, compassionate, and just. It is Nathan who delivers the famous “parable of the three rings,” attesting to the equal value and truth of the three Abrahamic faiths.

In family recollections, Alex Ganz, who would die of a stroke shortly after his two sons returned home from the First World War, was an ideal man of Bildung, an almost Goethean archetype. His son Karl Justus remembered him as “somewhat like an Olympian being”:

His whole person radiated the nobility of his attitude, the utmost integrity and conscientiousness, while at the same time revealing the artistic touch that gave him a special appeal.

(Alex, like his daughter, had wanted to be a painter.)

Gottfried wasn’t the only German Jew to look askance at the Jewish Bildungsbürgertum and deem them complacent. Radical members of the Weimar generation rebelled and turned to other paradigms: socialism, Zionism, forgotten traditions of Jewish mysticism, and various combinations of the three. Hannah Arendt, in a 1943 essay, when she was still a Zionist, writes that “the dignified restraint which society had so long considered a criterion of true Bildung” was in the crisis of the modern day “tantamount to plain cowardice in public life.” As the twentieth century ticked forward, Mosse judged, Jews “clung to the idealism of Bildung” in the face of a reality that had turned increasingly hostile, “chasing a noble illusion”: that politics could be subordinate to culture.

On the plane back to Cologne in January, I read the rest of Gottfried’s letters. The story that can be reconstructed from them is, of course, grim. Anna refused to leave Germany as long as Gottfried was still in prison; every two months he could receive visitors for fifteen minutes, and sometimes Anna and Helene would go together, though the young couple’s relationship was now illegal. (Helene was not Jewish.) The three made plans to emigrate and go to Argentina after his release. Gottfried’s messages are generally cheerful, plucky, full of exhortations to remain strong. Throughout the correspondence, he reassures his mother. She is alarmed by his appearance, his pallor and a shaking; he replies, “My health is completely fine, and I no longer know which devil caused me to ‘jerk’ like that during my previous visit.” At times he turns to extreme moral seriousness, declarations of principle. More than anything, he writes of books. The first thing he asks to be sent is the works of Lessing—Lessing the cosmopolitan, the rational and humane optimist. “I particularly crave philosophical literature,” he writes, “perhaps like a religious person craves the Bible.” He begins to teach himself English by translating Macaulay. I started to make a list of everything he read, which I would try to read myself, but I quickly gave up. It was impossible. Nietzsche, Schopenhauer, Herder, Jean Paul, Schiller, and Goethe, Goethe, Goethe. He quoted Faust with his imprisoned comrades.

Gottfried’s politics did not seem so much to be a rebellion against but an organic continuation of Bildung. Informed that the German-Jewish journalist Kurt Tucholsky has killed himself, he judges it to be “entirely due to the consequences” of the man’s own ideas. When what heartens someone has been destroyed, “where can he find the strength to continue living if he doesn’t believe in a future. . . ?”

His socialism seems based on the moral improvability of humanity, a notion that not even the Nazis could shake from him. He writes in 1934, from prison in Herford, “Man is not bad—circumstances have made him bad. If circumstances changed, he would slowly, within a few generations, become good again.”

In 1939, when he is supposed to be released, Anna and Helene go to the prison to pick him up, but they are told he has been sent to a concentration camp. From Sachsenhausen, the letters grow shorter, just cards really. But still he deems Balzac’s Cousin Pons too “black and white”: “In reality, light and shadow are more evenly distributed.” His mother desperately pursues ways to get him out and emigrate, at one point falling victim to a confidence scam, but Gottfried seems to realize that this will be impossible. He doesn’t complain or even describe the conditions in the camp—the letters were subject to censorship—but he tells Anna, “The environment in which I live often seems too unreal that I think I’m dreaming.” His last letter is from September 1942:

My dears, thank you very much for your two letters, September 16th and 24th. You can imagine that I’m happy now. If a letter is a nice greeting, a small connection with freedom, how much more are the things you can send me. If I’m warm this winter, you’ve played a crucial part in it. By the way, I realize again that anticipation is the most beautiful kind of joy.

My health is good, but the long time that I have been separated from you makes reality seem unreal to me. I warmly greet you dear ones from another, more beautiful world.

With love, Gottfried

His last sign of life was a card to an uncle on his father’s side. Then, in early 1943, the uncle received a notice that the ashes of prisoner Gottfried Ballin could be retrieved at Auschwitz. After the war, his SAPD comrade Richard Rosendahl, who survived the camp, tracked down Helene and told her that Gottfried had been gassed after attempting to escape.

By early January, the death toll in Gaza had reached nearly twenty-three thousand. According to recent polls, the far-right Alternative for Germany party had the support of 23 percent of the country, and it had been reported that its leadership had in the fall attended a secret meeting with neo-Nazis and far-right organizers to discuss a mass-deportation plan for millions of “non-assimilated” immigrants, including those who had been naturalized as citizens. Meanwhile, in the name of fighting anti-Semitism, German cities were limiting pro-Palestinian demonstrations and arresting protesters. Faced with its bad conscience, it seemed the country could only repress.

A couple weeks before I arrived back in Cologne, a ceremony to honor the writer Masha Gessen, in the city of Bremen, had been canceled. Gessen was supposed to receive the Hannah Arendt Award but had published an essay comparing the situation in Gaza to Nazi ghettos; as a result, the Bremen senate had withdrawn its support, and the event was postponed and dramatically downsized. The irony here was not subtle: the prize is awarded for expressing “opinion in controversial political discussions,” and Arendt herself had been a critic of Zionism. I wanted to resist Gessen’s comparison as being too crude. Yet I’d seen a photo, printed by the New York Times on the first day of the year, of Palestinians waiting for food in Rafah—a line of women holding empty pans through the bars of a fence. It looked like something out of the Holocaust. Israel’s siege was creating a famine. I couldn’t help but think of Anna in the Łódź ghetto, where she had probably perished of disease or hunger. In my hotel room, on the cover of a complimentary magazine, was a photo of Jerusalem, of the Wailing Wall and the Dome of the Rock, with the text: “Frieden: ein Wunsch, der uns alle eint,” “Peace: a wish that unites us all.” Well, apparently not.

On the afternoon of January 9, I walked to the NS-Dokumentationszentrum, housed in a building that became the Cologne headquarters of the Gestapo in 1935. The research fellow who met me, Birte, was in her forties, and appeared as if she had been harrowed by her work. At various points throughout my visit, she looked like she was about to burst into tears. In her office in a newly constructed annex, she handed over some documents she’d prepared for me—ones relevant to my family and the bookstore. Really there was not much; she explained that many records had been lost in bombings or deliberately destroyed by the Nazis. In the first folder was a facsimile from a ledger by a Third Reich institute for racial research, which listed Anna among those deported to Łódź. In others were recent newspaper clippings about Lengfeld’s, advertisements for the store from the Nazi period, and an essay Gottfried wrote in 1932, in which he declares his interest in studying history, just before the Nazi seizure of power would prevent him from going to university. At least according to what he wrote, his political awakening had not come from Marxism—it was perhaps wise that he omitted his ties to the radical left—but from Zionism. In a Zionist hiking group, at the age of ten, he had learned, he said,

Jewish beliefs, Jewish customs, Jewish literature, and Jewish songs, which I had never known in my own family. I became an enthusiastic Zionist, whose greatest wish it was to go to Palestine to live as a farmer, and to take part in the building up of a Jewish Empire.

At some point, presumably, he abandoned the Zionist Youth for the Socialist, though this certainly complicated my picture of him as a resolute internationalist. But back then, the boundaries of these ideas had not yet become fixed: the potential utopias flowed into each other.

Birte brought me to the older, main portion of the building, where the walls had a rough yellowish paint job—an attempt to return them to how they’d looked just before the Gestapo took over. After the war, the building had been used by the American occupation forces. I was comforted a little by the thought of mordant GIs putting their feet up on the furniture, throwing their smokes on the ground. After the Americans left, the building had housed municipal offices: people who had once been imprisoned or tortured there would have had to return to get their marriage licenses.

Birte explained that historians didn’t know what much of the building looked like while the Gestapo used it, so to attempt to replicate it would have been “too Disneyland.” But preserved as it had been was the basement, where the prisoners of the secret police had been held. This was the most important thing in the building, Birte told me, and guided me down the cement stairs. At their foot was a tall, burly guard dressed in all black. He smiled at me, which did not make me feel better. The ceiling was low. Birte pointed out the open shower area where there were also troughs that served as toilets. The showers. I did not like the sound of this. Then she showed me the cells. Each had a metal-plated door with a peephole. They were long and narrow, maybe five feet by thirty. They had been designed for two, she explained, but by the end of the war around twenty prisoners were kept in a single chamber. Not great. She pointed out the prisoners’ graffiti on the walls: dates, names, hash marks counting the days imprisoned. I saw a small portrait scratched in profile. Whatever happens, I’m not going in one of those fucking cells. She led me to a corridor, rattling off what seemed to be a very precise account of the facts, but I had stopped fully listening and was just nodding politely along. On the right side of the corridor were three more cells, and the hall terminated in a small room with a light on. Perhaps the interrogation room. I stopped. My vision grew a little blurry. Why were they so eager to get me down here, anyway? Vague discomfort bloomed into full-blown paranoia. “I’m sorry, but I can’t go in there,” I announced. “I think I need to leave now.” Birte was very understanding. I hurried up the steps and said my goodbyes as quickly as was possible. Later, I would learn that the room at the end of the hall had been a guardroom. It now served as the memorial for victims of the Nazi regime, including the hundreds of prisoners who were shot or hanged in the building’s courtyard.

I rushed back to the hotel. I hated hearing German voices on the street. Part of me wanted to take my new German passport and throw it in the trash or burn it. My room was generously stocked with free Kölsch beers, and after one, I felt a bit calmer. I made my way down to the bar, where I decided to eat dinner. The idea of a big, Teutonic Brauhaus near the cathedral no longer sounded appealing. The hotel lobby was full of older men in funny green suits and hats. It was for Karneval, the bartender told me. Oh, I thought that was later, I said. He turned his back to me to polish some glasses. He seemed surprisingly bitter and annoyed. “No, that is for the drunk tourists. The real carnival has begun for us Kölners much earlier.” From the dining hall next door, the men in funny suits were singing together, clapping, and stamping on the ground.

The next morning I returned to Lengfeld’s. I had told my Instagram friend I was coming, but when I walked in, an employee I’d met before gave me a somewhat alarmed double take and then scurried into the adjoining storefront. I had brought a galley of my book, which I’d inscribed to the store. I gave it to the clerk, who seemed a little puzzled by the gesture. He seemed a little puzzled about everything. He noticed the dedication: for gottfried ballin.

“Oh, I know him from the book.” He pointed toward the Bilzes’ volume on my family and Lengfeld’s, displayed near the register.

“Yes, he worked here!”

“Yes, briefly, I think.”

Yes, briefly.

“Are you staying in Germany long?”

“No, not long.”

Don’t worry.

I took my time in the store, pulling lots of books off the shelves and sitting in the chairs. I wanted to find some of the things Gottfried had read in prison. I got a complete set of Goethe’s poems; Heine’s Deutschland: Ein Wintermärchen also felt appropriate, since I, too, was a Jew on a winter journey to Germany. I asked if they had any of Lessing’s works. The clerk went to check and came back with all they had: a student’s copy of Nathan der Weise. I laughed a little as he handed it to me. He didn’t see the irony. When it was time to pay, he gave me Nathan der Weise for free.

“I wonder if I could ask you for something else?”

“Of course.”

“Could I have one of those?”

I pointed at the card paper with the owls on it. He seemed not to see what I was pointing at. I tried my limited German.

“Die Eule. Die Eule.”

A look of incomprehension. I walked behind the counter and took one of the owl cards. Aggressive Jew.

That evening, I brought my laptop to the hotel bar to read through Gottfried’s letters again. Did I like Gottfried? Maybe not. Sometimes his opinions seemed dull or sententious. All that uprightness. Priggish, moralistic, so predictably and tediously virtuous. Was I also disappointed he wasn’t a genius? He was not as witty as Heine, as subtle as Arendt, as penetrating as Karl Kraus. Judging the martyred dead, John? Very nice. He was only twenty when he was arrested, after all. He stood up to the Nazis and they killed him—now you want him to be Walter Benjamin too? I didn’t like the way he talked to his girlfriend sometimes. She had apparently gone to carnival with a friend—possibly more than a friend. She obviously felt a little bad about it, but he scolded her at length for supposedly giving up the values of the youth movement and stepping in a “petty bourgeoisie” direction: he expounds on the failure of drinking alcohol, questions her newfound interest in dancing, and deems carnival “an opportunity for dissatisfied and inhibited people to . . . undertake actions that they reject as immoral the rest of the year.”

Clearly he was jealous. His fiancée was out there in the world; he was stuck in prison. He had no control over anything. Later, he catches himself a little: “As I read through the letter, I see that I have sounded like a pedant.” Then: “Now to Goethe. In my opinion, you are making a mistake . . . ” He was very concerned that Helene, who came from a working-class background, got properly gebildet. More than a little condescension creeps in. “Try setting yourself a task in a specific area of knowledge that you will work on exclusively. Otherwise, the danger of wasting your work force is so obvious.” He writes his mother fretting over Helene’s “development.” Perhaps it was a comfort, a necessary delusion, to believe Helene needed rescuing, when it in fact was him. She couldn’t have minded too much, I guess: after the war she took the name Ballin and in the 1950s was granted a posthumous marriage to Gottfried. They were in love.

Gottfried had also made fun of my family a little bit—seemed to judge and almost literally dismiss them, while implying that they might not risk dirtying their gloves by shaking his hand. He writes to his mother:

I send warm greetings to Aunt Resi, the sensation, along with other relatives, if they intend to accept greetings from a prisoner on remand. But the “geese” should leave Pino and Aunt Lisbeth here; they have the tradition of Eretz Yisrael and a bunch of Hebrews over there, so they can leave the two of us alone.

The German word for goose is Gans, a homophone of our surname. When the Ganzes left for Palestine in early 1934, Pino and his wife Lisbeth had stayed for a short time to try to mind the store. Gottfried was being glib, but wasn’t it dangerous and irresponsible to suggest that his aunt and uncle remain? According to what Helene told the Bilzes, Gottfried had wanted to teach in Palestine after prison. But the only mention of Israel in his letters was this ironic remark.

Was I also ashamed in front of Gottfried for my own weakness? Was this the reason for the Ganz silence? I couldn’t live up to the constant courage and purposiveness: the insistent, optimistic faith in the future, if not for himself, for mankind. I couldn’t even do the tour of the Gestapo cellar without going to pieces. How could I begin to face a fraction of the circumstances that he had and apparently with such bravery? (Of course, I have a clearer idea than Gottfried of where such passages end.) At one point in prison, he was reading the Bible. “I sit in the evenings like St. Jerome in his study poring over the Bible . . . ” The saint in his cell reading about the righteous prophets and kings.

In a sermon in 1904, a liberal rabbi described the process by which the German Jews had become members of the Bildungsbürgertum, saying, “From a martyr the Jew has become a bourgeois.” Then, a martyr again. And then, I suppose, a bourgeois once more. My schnitzel had arrived.

Back in Manhattan in February, I searched the New York Public Library for more information on the Jews in Cologne. In the Rose Main Reading Room, on a microfilm machine, I turned through the dissertation of a scholar named Shulamit Magnus. In the late 1830s and ’40s, in a dramatic shift, the Cologne bourgeoisie had formed a partnership with the Jews. The city fathers gave speeches on tolerance, newspapers editorialized in favor of emancipation, and Jews joined the great civic societies. What had suddenly changed? The bourgeoisie wanted modernization, and Cologne would have to grow to stay a trading center. Cologne needed a railroad. But who could come up with the capital for such a massive project? The answer was the banking house of Oppenheim—run by a family descended from court Jews and advisers to the city’s prince-archbishops, who could provide both money and connections to their aristocratic cousins in Paris, Hamburg, Brussels. With this alliance came an understanding: the Oppenheims’ brethren would have civic rights.

Cologne and its Jewish population grew rapidly, and the city was at the cutting edge of German liberalism. A newspaper co-funded by the Oppenheim family and gentile entrepreneurs employed both Karl Marx and Moses Hess, godfather of Labor Zionism. “Cologne’s Jews,” Magnus writes, “served the business and consumer needs of Cologne’s ‘middle-classes,’ to which they themselves for the most part belonged.” The big Oppenheims provided credit; the little Ganzes, books. Lengfeld’s, purchased by Alex Ganz in 1880, grew under our watch to hold the largest lending library in the Rhineland, with two hundred thousand volumes. Alex came up with a system by which the books could be borrowed and returned by mail, shipping in canvas bags with a double-hinged cover: on one side was the customer’s address, on the other Lengfeld’s. The books traveled all over Germany and the world, including to diplomats posted as far away as China.

A terrible vision occurred to me as I read. The Jews had helped to build up Cologne, to make it a modern city, to spread Enlightenment, to industrialize it. Then, the tide changed, and the Jews were swept away. Their old friends in the bourgeoisie might have shed a few crocodile tears for their colleagues, and certainly for all those wonderful musicians and writers, but they were perhaps not so unhappy to see them go. The Jews were deported on the same rail lines they so eagerly helped to build, into the maw of industrial liquidation. Enlightenment really wasn’t needed anymore once you had the machines. There was no longer any purpose to these little Jews with their sentimental claptrap about art and culture, an art and culture that was never really theirs to begin with. Lengfeld’s would be Aryanized. The policy was successful.

The German-Jewish writer Moritz Goldstein once declared, “Our relationship to Germany is one of unrequited love. Let us be manly enough at last to tear the beloved out of our hearts.” Easier said than done, apparently. Even I still wanted to be accepted as part of that culture, all that bullshit: to be tied to the bookstore, to have a reading there, to have my photo up with all the famous writers, to keep our name in its name. I wanted to return from exile to Zion, to help perform the rites at the temple of Bildung. I wanted them to embrace me. You’ve come back! At last! Maybe I was also offering my services: “Perhaps you need a Jew again? I can give your store a cosmopolitan sheen, build your international reputation, and help to assuage your guilty consciences.” But I was also an author, an artist—I wanted them to see. I was cultured; we were still cultured. They didn’t much notice. Instead, I seemed only to scare them. Memorials are placid enough. It’s much more unpleasant to face a relict. I was the living dead, a ghost.

Unlike a Palestinian, I was able to exercise my right of return. And I was no longer who the German right wing had in mind when they talked about denaturalizing people. But what really remained for me there? The world my family lived in and helped sustain was gone forever. That was made evident.

Before the Germans came to view the Jews as parasites, they often viewed them as walking fossils. The Jews had persisted in existing though their religion had been superseded by Christianity and they had no land or state of their own. They had no clear place in the unfolding drama of humanity. According to Hegel, in the words of the scholar Shlomo Avineri, they were “in history but not of history.” They were a remnant people, scattered across the world. Perhaps I am a remnant of the remnant: I am one of them, but less so. Less righteous, less learned. I am, as the Germans say, halbgebildet, half cultured, carrying books back to America with me that I can’t really read.

In 1933, the Ganz family celebrated their final New Year’s Eve in Germany, gathering and exchanging poems, as was their tradition. Beate recalled the scene: a punch of fruits and cognac, white wine and champagne, distributed into glasses by crystal pipette. Shortly before midnight, the poets recited their work, and at midnight the last poem “would bury the finished year and celebrate the birth of a new one.” “With this last toast,” she wrote, “the gathered family buried much more than just a difficult year: they buried—more or less foreseeing this—the era of happiness and balance.”

The poems, saved by Resi, are touching, sweet, sad, but also funny and witty: all that drilling of Faust had made the family canny versifiers. Felix’s poem particularly struck me:

I left my hair in Pillau by the sea,

My loves are scattered around the world,

I find it hard to breathe the air in Europe,

I’ve already stayed in Germany for too long.

Before me lay a thousand and one nights,

The days have, God knows, blurred together,

Father Alex always spoke

Of bones all dried out in the desert.

Still, I won’t waste away, and won’t let my bones dry,

Give in to the bookseller’s peasant life,

And say: Amen, so shall it be,

In the chosen, promised land.

But the land did not deliver on its promise. Felix tried to start a factory that would make candies but failed. In 1937, at the age of fifty-two, he died of liver disease. He drank himself to death, my grandfather said, finishing a bottle of brandy every night. He never seemed drunk, only depressed and worried. Learning in prison of Felix’s death, Gottfried wrote to his mother: “Poor Uncle Felix seems to have suspected that we wouldn’t see each other again.” When they were last together, Felix had refused to allow him to pay for a book he’d ordered. “Who knows if I’ll ever be able to give you something else,” he said. Felix had sang “Hatikvah,” the anthem of the Zionist movement, as his train left Cologne.

The Ganzes would not stay in Palestine. By 1938, the last of the family had left.

As much as I prefer Gottfried’s anti-fascism to Zionism, his stand sometimes appears futile to me. His little group accomplished next to nothing before the Gestapo found them out. In his insistence on remaining in Germany, he sacrificed both his life and his mother’s. I can recognize the nobility of his actions, but did Gottfried the martyr serve the world? If his politics were impracticable even then, surely by now they are just a footnote.

And as much as I want to wash my hands of it, I’m forced to admit that the Zionist project provided my family a temporary refuge that likely saved their lives. Were they colonists? If so, they were ones that would have much preferred to stay home. And yet we have a photograph, taken around the same time Gottfried would have been shivering in his cell in Herford, of my grandfather Peter in Jerusalem, tan, healthy, and smiling, wearing the khaki shorts of the Haganah, the Jewish community’s self-defense force. But Peter did not strike roots in the soil of Palestine. (According to my father, he had joined the Haganah only so he could break curfew and visit his girlfriend.) After his father’s death, he returned to Europe, to the Lobbenberg side of the family, now in Paris. The Nazis would invade France two years later.

It’s easy to despair of the world’s possibilities. The headline of one issue of the socialist magazine Gottfried distributed read die toten mahnen (“The Dead Admonish”). Standing in the cemetery in Cologne, I had felt admonished by the dead, but I could not and cannot say exactly in what direction. They speak to me in a language I can’t understand but must still try to translate. I will remember them. I will keep their faith and traditions, which, in their hopeless longing, in Gottfried’s desire for “another, more beautiful world,” hold for me infinite hope. I will keep the dead safe.

Above the cemetery gates in Cologne it is written: the righteous lives in his faith. These are the words of God, addressing the prophet Habakkuk, who asks:

How long, O lord, shall I cry,

And Thou wilt not hear?

I cry out unto Thee of violence,

And Thou wilt not save.

The Lord replies:

Write the vision,

And make it plain upon tables,

That a man may read it swiftly.

For the vision is yet for the appointed time,

And it declareth of the end, and doth not lie;

Though it tarry, wait for it;

Because it will surely come, it will not delay.