A missile fired by Syrian government forces over Aleppo in April 2013 © Nish Nalbandian/Redux. Nalbandian’s book A Whole World Blind: War and Life in Northern Syria was published in 2016 by Daylight Books.

It was March 22, 2011, and we were watching the Egyptian Interior Ministry burn. My father, my sister, my wife, and I were all crammed into a van on Sheikh Rihan Street in Cairo. Traffic was gridlocked. Dense clouds of smoke rose from the building at the end of the block—the building that had been the headquarters of the Central Security Forces. Hundreds of protesters streamed past our vehicle. Ash-Shaab! Yureed! Isqat an-nizam! they shouted. The people! Demand! The fall of the regime! They were angry, yes, but the mood was also jubilant. Only weeks before, important parts of the regime had fallen. The dictator was gone. And now, if the offices of the state police could burn, then almost anything seemed possible. Egypt’s autocratic rule was crumbling; democracy was ascendant in the region; the primary emotional note, in public discourse, was hope.

This hope was contagious. We’d returned, with my ailing father, to see the country where he’d lived until the age of fourteen. Over the course of that trip, he’d been transformed from a recalcitrant Arab to an ebullient one. He talked about wanting to relearn whatever Arabic he’d forgotten, about wanting to move back, to spend part of each year—Seattle’s rainy winters, perhaps?—in Cairo. He’d begun writing his name, Yusef, as![]() once again, his hand shaking with the labor of it. I will never forget the taxi ride from Zamalek to Heliopolis, when he and the cabdriver sang, in perfect harmony, a half-dozen songs by Umm Kulthum.

once again, his hand shaking with the labor of it. I will never forget the taxi ride from Zamalek to Heliopolis, when he and the cabdriver sang, in perfect harmony, a half-dozen songs by Umm Kulthum.

Though we didn’t know it, that geopolitical moment, so precious, was disappearing as quickly as it had appeared. Just a year later, in May 2012, I traveled to Beirut, the city where my grandmother was born. In Lebanon, I could feel her presence, could hear her voice in the voices on the street. The food she’d cooked for me throughout my childhood—food that had felt like a secret language—was everywhere in that city. Warak enab, the boiled grape leaves stuffed with salty lamb and rice. Kibbeh bil sanieh, the baked-meat dish with pine nuts, cumin, and dried rosebuds. And real hummus. Hummus with the texture of a milkshake and enough garlic to make your eyes water.

The Toutonghi family is large and sprawling, and it has been infused, each generation, with dozens upon dozens of children, all spread across a region stretching from Aleppo in the east to the Turkish city of Iskenderun on the shores of the Mediterranean Sea. Our emigration began in earnest with the departure of my grandfather’s generation in the early Twenties. My surname, as it crossed border after border, changed constantly.![]() became Tutunji and Toutoungi and Toutongi and Toutounghy and Toutonghi: a new definition of self with each new country.

became Tutunji and Toutoungi and Toutongi and Toutounghy and Toutonghi: a new definition of self with each new country.

People search for survivors in the rubble of a residential building, Aleppo, March 2013 © Moises Saman/Magnum Photos

I’d planned that May to visit Aleppo, just five hours to the north and the place where my grandfather was born. But the Syrian civil war had already begun. The borders were formally closed to U.S. citizens. In some ways, this meant that I’d be continuing a family tradition. Born in 1898 in the Aleppo vilayet, my grandfather had spent most of his adult life longing to return to the city. In 1974, at the age of seventy-six, he’d written to his cousin—Athanasios Toutoungi, once the Melchite Catholic archbishop of Aleppo—and asked if it was too late for him to emigrate back to Syria and become a priest.

“It is never too late,” the archbishop wrote back. “You can still become a priest if you wish … especially because you have such a melodious voice, and your melody is church-like and Byzantine.” But, the archbishop continued, the war nearby—the 1973 Yom Kippur War—had made travel dangerous and complicated. “We pray to God, the All-Knowing,” he added, “that peace will reign in the quarreling territories.”

I can’t help but wonder if Athanasios Toutoungi felt somewhat like I did in the summer of 2012, as I watched the protests in Syria spiral into war. By July, Aleppo was becoming one of the worst sites of urban fighting the twenty-first century had seen: the Free Syrian Army and other rebel groups battled Bashar al-Assad’s Syrian Arab Army in the city’s streets and in the surrounding countryside. No one emerged victorious. The resulting stalemate created a divided, besieged city whose supply lines and access to fresh water had been cut. It is difficult to overstate the suffering of these years in Aleppo, when more than twenty thousand of its civilians died. Four years of siege, of incessant artillery bombardment from both sides; four years without consistent access to food, heat, or water. Then, in 2016, government forces retook the territory. That battle pulverized much of the eastern part of the city.

All across Syria, the human cost is almost unfathomable. The fighting has displaced more than twelve million Syrians (out of a prewar population of roughly twenty-one million). More than five million refugees left, and millions more fled to provisional camps within the country. From 2016 to 2020, the government gradually expanded its areas of control, but large sections of the country remain contested, and remnants of the Islamic State continue to influence certain pockets. Kurdish separatist forces control a crescent-shaped area on the Turkish border. Swaths of Idlib province, which is bisected by the M5 highway between Damascus and Aleppo, have become chaotic and roiling, populated by Islamist rebels and refugees, many of whom are living in improvised settlements.

Even prior to last year’s earthquake—which ravaged the country’s northwest regions, the ones most affected by the lingering war—these divisions had calcified. Life in Damascus and the provinces surrounding the capital is relatively peaceful. But drive an hour to the north and you’ll see the Iranian flag flying over bombed-out cities. And two hours north of that, you’ll likely see the banner of Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham, the Organization for the Liberation of the Levant, an Islamist group that is still fighting Assad. The war is over until it suddenly isn’t. Militants detonate bombs at Shiite shrines, the Islamic State kills thirty soldiers at a desert station, Israeli missiles paralyze the country’s airports. According to the Syrian Network for Human Rights, 1,032 civilians in Syria died in armed conflict last year.

A Syrian general and two soldiers gaze across the city of Palmyra from a medieval citadel, April 2016 (detail) © Lorenzo Meloni/Magnum Photos. Meloni’s book We Don’t Say Goodbye was published by GOST Books.

Yet for the first time in more than a decade, the Syrian government recently began approving entry visas for Americans. And while the U.S. State Department’s level 4 advisory (“do not travel to Syria due to terrorism, civil unrest, kidnapping, armed conflict, and risk of unjust detention”) certainly gave me pause, I was desperate to see what had become of my extended family. I also worried that the war would flare up again. I was anxious that regional proxy battles between Israel, the United States, Russia, and Iran would once again slam the border shut. I booked a flight.

Once I had a ticket, though, the questions I’d had in 2012 no longer felt relevant. My family’s history, my inherited language—a knowledge of which I’d hoped to rebuild and pass on to my children—seemed less significant when placed against a backdrop of civil war. The decade since the Arab Spring had been a decade of violence, tragedy, and disease. In December 2017, my father died. His absence created, for me, an unmooring from our family history. I also worried that, even in private, I was unable to fully articulate the precise motivations for my trip. I wondered whether I would feel closer to my family history if I could repair the broken relationship I had with the country in the present day. Was that even possible? I had an earnest desire to understand Aleppo, yet I felt certain that I’d be seen as an interloper.

“But this is our traditional storytelling, habibi,” the Syrian-Armenian-American writer Sona Tatoyan would tell me once I arrived. “Our stories don’t begin with ‘Once upon a time …’ Instead, they begin with a contradiction. They begin with ‘There was and there was not.’”

The easiest way to get over the border, I learned, was to fly into Beirut and then drive the many winding miles of the Beirut–Damascus International Highway. So that is what I did, on a bright, clear day in mid-July of last year, when the cool wind off the Mediterranean made the Anti-Lebanon Mountains pleasant and hospitable. I hired a driver, Samir, and headed east. On my official paperwork, I wrote![]() —teacher and translator.

—teacher and translator.

There couldn’t be a greater contrast between the stretch on the Lebanese side of the border—choked with billboards advertising consumer goods of every kind—and the miles after lafrontière syrienne, which are mostly barren, punctuated by the occasional army checkpoint or poster of Assad. The Syrian Arab Republic has been a nominally socialist nation for the past sixty years, and the lack of commercial signage reflects this fact. The arid foothills leading toward the Damascus oasis remain largely undisturbed. They scallop downward into an ocher-colored catchment, looking roughly as they have since biblical times.

We reached our first checkpoint within fifteen minutes. As we approached the soldiers—one of them holding a Soviet-made AKS-74U with a wooden grip—Samir folded a Syrian banknote and slipped a pack of Marlboro Reds into the well of his door. He glanced at me and nodded, placing the money in his palm and rolling down his window. What unfolded had the choreographed precision of ballet. The soldier shook Samir’s hand, took the bribe, and with a kind of tight-lipped efficiency, opened the door to remove the cigarettes. As we drove away, I asked if this was normal.

“It depends on how much luggage you have, j’hani,” Samir said. “For one or two bags, it’s one pack of Marlboros. For three or four bags, it’s two.”

As we arrived in Damascus, it quickly became clear that the situation on the ground was desperate. The Syrian pound was plummeting in value and, by late July, would reach a record-low exchange rate of 13,158 to the U.S. dollar. When I got to the city, the functional exchange rate was 9,000 to the dollar. Within two weeks, the currency had lost roughly a third of its value. A friend of mine went to al-Wissam Sweets and bought us a box of barazek, the crunchy, buttery sesame-seed-and-pistachio cookies. Two weeks before, I was told the box had cost 35,000 pounds. That day, it cost 52,000.

Milk, eggs, vegetables, black-market gasoline: all these things were doubling in price, and then doubling again. The government issued subsistence rations of rice, bread, and sugar, but the portions were meager. Electricity was also a desperate problem. Nationwide, power consumption in 2021 stood at 15 percent of what it had been before the war. During my visit, the Ministry of Electricity provided roughly four hours of subsidized power per day, but the hours were unpredictable. State circuits often came alive in the middle of the night for a two-hour spell. Households and businesses that could afford it rigged some kind of backup, either a diesel-powered generator or a bank of solar panels on the roof. Power cuts affected access to drinking water, education, and medical care. In the winter months especially, students lacked sufficient light and heat in their classrooms. Subterranean water pumps, blood banks, medical imaging equipment, ventilators, dialysis machines, NICU incubators, and countless other devices rely on a consistent supply of energy. In rural areas, many government services have simply ceased to exist. Urban centers are not much better. “Electricity,” read a March 2022 humanitarian report facilitated by the U.N. Development Program, “has become … an existential concern for vulnerable Syrians.”

Fueling this collapse was the relentless sanctions regime, which was escalated under the Obama Administration in 2011 and compounded by the Council of the European Union. While some of these measures were clearly related to the war (for example, a ban on the importation of European- or American-made weapons), others were less so. There could be no Visa or Mastercard transactions in the country. Many Syrians found themselves unable to use international bank accounts, even those sending home small remittances from abroad. No E.U. or U.S. citizen could help anyone in Syria build or maintain a power plant. Syrian air carriers could not land at E.U. or U.S. airports. In effect, no Syrian citizen could be a global citizen.

“They want to keep us here,” Samir told me. “Because they know if we leave, we’ll never go back.”

My dad was a member of a particular class of traveler; upon arriving in a city, he’d first seek out the largest Catholic church, where he’d make a donation and light candles for the entire family. My childhood was full of visits to musty vestries in Milwaukee and Memphis and Marseille, as my dad wrote traveler’s checks to various priests in his most formal handwriting.

It seemed appropriate that as soon as I arrived in Aleppo I had dinner with the city’s Melchite Catholic archbishop emeritus, Jean-Clément Jeanbart, with whom I’d been in sporadic touch over the past decade. Jeanbart had four brushes with death during the war, and his home had collapsed during the 2023 earthquake.

The first earthquake occurred on February 6, a few minutes after 4 am. It radiated out of the East Anatolian Fault and, together with its aftershocks, was one of the deadliest seismic events of the decade, killing more than 53,000 Turks and 7,250 Syrians, compounding the suffering of a nation already badly damaged by war. The World Bank has estimated that Syria alone sustained $5.1 billion in direct physical damages, an amount that equaled approximately 10 percent of the country’s GDP. When Jeanbart’s home was destroyed, his bedroom had somehow been partly preserved; he’d managed to crawl across the rubble to safety. He was now living in his brother’s apartment.

Jeanbart and I sat on the patio and ate slices of watermelon and long strings of jibneh, the salty Syrian cheese that’s studded with black cumin seeds. It was remarkable to meet, in person, a man who could recall my first cousin twice removed, Archbishop Athanasios Toutoungi. Athanasios had been a towering figure in the dinner-table storytelling of my childhood; he and my grandfather had been born within a year of each other in what was then the Ottoman Empire. They’d been close friends and had each trained to become priests, Athanasios in Ottoman Turkey and my grandfather in Thonon-les-Bains, France. But while Athanasios was ordained, the First World War compelled my grandfather to leave the seminary. The French government repatriated him in 1914 to present-day Syria, where he joined an extranational fighting force called the Legion of the Orient. He shipped out to Cyprus, then to Cairo, and eventually he used a Syrian refugee visa to emigrate, with his young family, to Bakersfield, California, in 1946.

In Aleppo, Archbishop Jeanbart and I talked about all of this. But while I wanted to discuss the past, he wanted to focus on the future. He was enthusiastic, in particular, about the diocese’s many building projects, all of which had been completed within the past six years. He’d supervised much of this construction himself: nearly two hundred apartments in several buildings that were rented to families at a subsidized rate, 30 percent of what they had been paying previously. Jeanbart saw this process as a necessity, a holy calling. It was the primary way that he could help stem the flow of emigration—especially Christian emigration—from the country.

“And the school!” he exclaimed. “You have to see it right away.” He glanced at his watch. It was nine o’clock at night. He shook his head. “Maybe in the morning,” he said.

The next day, the archbishop and I drove across the city to Dahiyat al-Assad, a suburb of Aleppo, where École Amal had been one of the most prestigious K–12 institutions in the country before the war. During the conflict, however, its campus had become a battlefield. Even now, six years after the cessation of fighting, the surrounding neighborhood was in ruins. Two houses had been rebuilt; the rest were vacant. The school building itself was newly whitewashed. Its concrete surface shone in the July sun, but it was hard not to notice the surrounding devastation. The neighborhood was eerily quiet. No birds. No traffic. No human voices. Just a space sanctified by the men who’d bled and died on this ground. I felt a sharp and sudden shame. What idiotic fantasy of return was I indulging? I didn’t belong to Aleppo any more than I belonged to Beirut, to the Latvian cities of Liepāja or Rīga, or to Cairo. These were the five cities where my parents and grandparents had been born. But I’d been born in Seattle in 1976. As much as I’d never felt like it, I was an American.

I heard the archbishop’s car, a tiny aging Renault, creep up behind me. “One more stop,” he called through the open window. “Get in.”

We drove to downtown Aleppo to the Melchite archeparchy’s twelve-story apartment tower, easily one of the tallest structures in the city to my eye; somehow it had survived the fighting and was finally completed in 2019. After greeting the doorman, we got into a coffin-size elevator and rattled into the air before stepping out onto the roof. There, stretching from horizon to horizon, was all of Aleppo, one of the oldest continuously inhabited cities in the world. The sunlight was incandescent. We stood there for a moment. The archbishop raised his left hand, cupped his fingers together, and softly said a prayer for the city he loved. Then he turned and, startling me with the strength of his grip, grabbed my arm.

“The school,” he said. “That’s how you can help. Twelve thousand. It will buy food, housing, books, everything, for twelve girls, for a year.” Many of these students would likely be orphans, he continued, girls who’d lost not only their parents but their entire extended families in the fighting.

Twelve thousand dollars, though, was a lot of money for me, especially given the fact that it would be difficult to stop giving once I had started. Later that night, I called my wife on WhatsApp, since American cell carriers don’t provide coverage in Syria. We spent hours researching how to make a donation only to find that it would be illegal. Sanctions barred the transfer of any form of material assistance to Syria, a fact that made helping Syrians virtually impossible for anyone who wanted to follow U.S. law. If I tried to pay the twelve thousand dollars per year that it would cost to sponsor those girls, I would risk having my bank accounts frozen by the government.

But in the moment on the rooftop, before I knew that, I nodded, a little shocked. “Of course,” I said, after a moment. “Yes.”

Jeanbart turned back to the view of the city. He was quiet again. “It’s good to have met you,” he finally said. “I’m glad you came.”

Economic warfare is arguably as old as the javelin and the catapult; Sparta won the Peloponnesian War, in 404 bc, in part because of the starvation caused by its blockade of Athens. But it wasn’t until 1920, and Article 16 of the Covenant of the League of Nations, that sanctions became a formal tool of the international world order. After the catastrophic battlefield losses of the First World War, economic measures were seen, by many politicians of the era, as a nonviolent alternative to combat. “Apply this economic, peaceful, silent, deadly remedy,” Woodrow Wilson said in 1919, “and there will be no need for force.”

It was a simplistic assessment. In his book The Economic Weapon: The Rise of Sanctions as a Tool of Modern War, Nicholas Mulder argues that sanctions—sometimes applied over many decades against defiant nations—have completely remade the world’s understanding of war and peace, blurring the boundary between these two conditions. “What made interwar sanctions a truly new institution,” Mulder writes, “was not that they could isolate states from global trade and finance. It was that this coercive exclusion could take place in peacetime.” For the citizens of a country enduring sanctions, life is lived in a state of forever war.

There is a growing sense that endless, sweeping sanctions are inhumane, but progress against them is slow, fitful, and disorganized. In December 2022, a U.N. Security Council resolution did institute a humanitarian exception in all fifteen of the sanctions regimes overseen by the body, but enforcement has been piecemeal. And since Syrian sanctions don’t fall under U.N. oversight, the country did not benefit from the resolution.

After the 2023 earthquakes, the United States, the United Kingdom, and the European Union established a 180-day exemption for humanitarian assistance to Syria for earthquake relief. But the exemption expired in August and was not renewed. And even though President Biden’s Treasury Department has been more critical in its recent self-assessments (“Treasury must address more systematically the challenges associated with conducting humanitarian activities through legitimate channels, in heavily sanctioned jurisdictions,” a review noted), its language is hardly revolutionary. Archbishop Jeanbart’s description seems most apt. These sanctions are “knowingly established to prevent reconstruction, rehabilitation and economic recovery,” he wrote in 2021. “You can imagine the distress in which most of our families find themselves, almost all of them needy and on the edge of misery and despair.”

This misery takes many forms—economic, spiritual, physical. The day after my dinner with Jeanbart, I walked into the souks we had seen from the roof. For millennia, these markets had been a critical part of the daily life of the city. But that morning only a few shops were open. I bought some sour cherries and went in search of a soap vendor; my grandfather’s childhood memories were filled with the scent of soap made from laurel oil. (Toward the end of his life, we’d tried without success to find it for him in the Pacific Northwest.)

As I walked, I focused on the collapsed houses, the thousands of bullet holes gouged into the souks’ walls, the larger scars left by mortars and IEDs, and so I only gradually became aware that a few steps in front of me—carrying clipboards and wearing bright-white mushroomlike hard hats over their hijabs—were two young women in overalls. They were incongruous in the otherwise muted morning light.

I followed them. They led me down a crowded market street and to a small unmarked office. I hesitated at the doorway. Other than the two women, who immediately sat down and began to work, I saw one other person: a man sitting at a desk at the back of the room. He looked up and raised an eyebrow, and I immediately apologized, explaining that I was a visitor from the United States and curious as to what they were doing. “The United States?” the man asked, surprised. He waved me over. “Come in,” he said. “Sit down.”

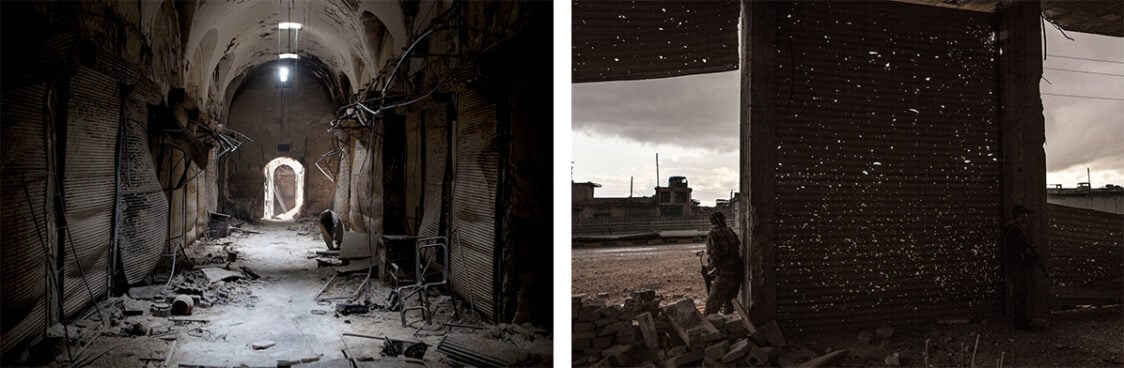

Left: A souk in the old city of Aleppo, October 2012

Right: Aleppo, February 2013. Both photographs © Jérôme Sessini/Magnum Photos

I’d discovered, quite by accident, the offices of the Aga Khan Trust for Culture, one of the few international organizations working to restore the public spaces in Aleppo. The man behind the desk was Roberto Fabbro, the project director at the time, and he’d been leading the field office for the past six years. That day, and in subsequent conversations we had after I left Syria, Fabbro was open and improvisatory. He described his decision to come to Aleppo, at a time when the last battles of the civil war were still being fought, as almost happenstance. “In the office, they asked: Who wants to go to Syria? There was no one else to do it. So I volunteered.”

The Aga Khan Trust for Culture is in significant part funded by the private wealth of Aga Khan IV, the forty-ninth imam of the Nizari segment of the Ismaili Shias. The Nizari imams claim direct descent from the Prophet Mohammed; it has been rumored that the current khan’s personal fortune is $13.3 billion.

Aleppo’s open-air markets are part of a UNESCO World Heritage Site, but they were largely destroyed by the fighting. They consist of some fourteen kilometers of domed, stone walkways with thousands of recessed alcoves for vendors. The restoration is a yearslong process, one that involves a fleet of laborers and specialists: stonemasons, carpenters, structural engineers, architects, urban planners. Materials must be matched to what remains of the structure. The stability of every meter must be confirmed using 3D-modeling technology. Damaged stones must be removed one at a time, new stones cut by hand and fit carefully into place. Wire brushes to clean, joint rakers to clear degraded mortar, carbide-tipped chisels to carve and repoint each meter of the wall: these are the tools of a slow, laborious, and resource-intensive process.

This work, Fabbro hoped, could be “really useful in terms of a social, economic intervention,” by reopening the shops for those who had lived in the old city. Much like the archbishop, Fabbro imagined a thriving Aleppo, a city that had freed itself of the specter of war. But this wouldn’t be possible, he warned, without international partners. “Over fifty percent of the old souks of Aleppo are damaged, and this will need a lot of money for rehabilitation,” he told me. The sanctions, however, make this work almost impossible. “Many of the countries that the Aga Khan is used to working with—Norway, Sweden, Switzerland—they were not able to participate financially,” he said. “Whatever they could do in Syria would lead to punishment by the U.S. government.”

Eventually, I left the offices and headed back to my hotel. The day had grown hot, but the electricity was out. A few buildings had generators, and their whining, purring motors filled the old city with a kind of low-toned tinnitus. I thought about what I’d encountered. Inflation was soaring; the archbishop needed twelve thousand dollars to educate a dozen girls; the Aga Khan Trust for Culture was struggling to find international help for its work. Meanwhile, whole sections of Aleppo were still no more than rubble. And numerous settlements in the surrounding area—Saraqib, Kafr Nabl, Sarmin, Afes, Balyun, and many others—had been flattened or erased by artillery, missile strikes, and bombing.

Toward the end of my time in Aleppo, I had dinner with my third cousin Majd Tutunji, who, at twenty-four, was working full-time as he pursued a master’s degree in architecture. We ate at a restaurant in the Azizieh neighborhood of the city, just a few blocks from the home built in the 1890s by my great-grandfather.

Majd and I discussed our relatives from the distant past. We talked about how my grandfather’s and his brother’s flights from war had dispersed Tutunjis across the globe. When I was growing up, I told him, my father had first cousins in Toronto, London, Paris, Cairo, Berlin, Yerevan, and Beirut. They’d come to visit periodically—garrulous, mercurial men in overly formal clothes, a little like chain-smoking emissaries from the moon.

Majd worked for Ice Cube, one of the most prominent Syrian fashion labels, a brand that sold athleisure and had six retail outlets in government-controlled sections of the country. “I’m responsible for all quality management of the brand in Aleppo,” he told me. Majd’s English was perfect, much better than my poor Arabic, and we discussed the country’s economy. Before the war, Ice Cube had been affiliated with the Benetton Group, but the Italian company was forced to divest itself from the label.

Majd showed me sketches of the clothes he was designing for his new brand, Xtension. His phone was full of drawings and renderings of shirts and pants and shoes that looked, to me, like anything that could have appeared on the runways of European fashion weeks. I asked him about a post I’d seen, years before, on his Facebook page and subsequently always remembered: the photographs of a maquette he’d built, with his fellow architecture students, as the last battles of the war raged nearby. In a basement near the university, Majd and his collaborators had constructed a scale replica of the Taj Mahal. It was a luminous object. Its white simulated-marble towers were framed against a black-cloth backdrop.

Majd nodded. He remembered the project but deflected any praise. “The amazing thing,” he said, looking at me seriously, “were the maquettes my friends built of the ruins.”

He scrolled back through his photographs, and there, in stunning miniature, were scale models of the very devastation I’d just walked through. These were architect’s renderings, built laboriously by hand, a reconstruction of the country’s destruction. I scrolled through image after image. The point of an architect’s model is to convey ideas or, as in the case of the Taj Mahal, to commemorate beauty. But here were architecture students using their skills to bear witness. To say: This is how it was, here, in our country.

“Even if it’s repaired tomorrow,” Majd said, “with these models you’ll always know: This is what happened.”

On the last day of my trip, I visited the Khalid ibn al-Walid Mosque, in the al-Khalidiya district of Homs. The area was a flash point in the fighting, another site of a prolonged and bloody battle in the war. Much of al-Khalidiya remains destroyed even today. Nearly every window I saw was blown out, every exterior wall savaged by missile and artillery fire. Concrete had crumbled like cake. The structural metal had been stripped years before by looters.

The mosque, however, had been recently restored. Not by a local organization, or a U.N.-backed collaboration, but by a foundation run by the family of Ramzan Kadyrov, the head of Chechnya, a dictator known for the brutal persecution of his enemies and a man whom Human Rights Watch determined had overseen a regime of systematic torture in the Chechen Republic. It’s a remarkable foreign-policy initiative that transforms a foreign despot into a local hero. (There were, in fact, other examples of these kinds of projects in Syria, such as financial assistance from Hungary’s strongman prime minister, Viktor Orbán.)

As I stood in that domed, sacred space, I felt bleak and exhausted. It was hard to be hopeful about a single restored school or mosque rebuilt by a dictator within a terribly damaged city, especially when confronted by the intractability of the country’s ongoing crisis. It was a crisis intensified, of course, by Syria’s closest neighbors. The Israeli government’s “war between the wars” meant that going forward, the IDF would strike targets in Syria, with little restraint, as a form of self-defense. Whether these targets were suspected shipments of Fateh-110 ballistic missiles in May 2013, or senior commanders of Iran’s Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps at the country’s embassy in Damascus in April 2024, the result was the same: Syria would be trapped by foreign actors willing to use its territory as a theater of war. And the Syrian people, regardless of their geopolitical affiliations, would suffer.

As I looked around the interior of the mosque, a man stepped through the doorway. He was leading his two small boys by the hand. They were no more than four or five years old, and both wore oversize green T-shirts. He led them through their ablutions, helping them wash their hands and arms and faces. Then he walked with them to the center of that empty space—and knelt to pray.

Every evening, throughout my childhood, my father would come into my room, sit on the ground beside my bed, and say, with me, a prayer in French to the Holy Family. It was a prayer that he, in turn, had said with his father and brothers every night in Egypt. Jésus, Marie, Joseph, it began, je vous donne mon coeur, mon esprit, et ma vie. Though I’m not religious anymore, in any formal sense of the word, the sound of his voice still lingers on the margins of my memory. Reading the words now, I can almost hear him; his voice haunts the space around my own. Jésus, Marie, Joseph, faites que je meure dans votre sainte compagnie. When my father died, we engraved the prayer on the lid of his coffin.

At the mosque in Homs, the man’s sons—wide-eyed, barefoot—tried to mimic him. They knelt awkwardly, glancing over at each other, trying to gauge if they were doing it right. Standing there, in the open space of the mosque, their father was giving them a complex gift. They’d always remember these words. For the rest of their lives, they’d use this same vocabulary, these same gestures, to access prayer. But in prayer, I wondered, would there be peace, or more suffering? Would there be consolation?