All photographs from South Korea, February and March 2024, by William T. Vollmann, for Harper’s Magazine © The artist

Listen to an audio version of this article.

i. “the nightmare scenario”

In January, Kim Jong-un, aka the “Respected Comrade,” declared South Korea an enemy state and formally turned down the prospect of reunification. Talking heads promptly deemed the situation on the Korean Peninsula more dangerous than at any time since the Korean War. Curious to see those border tensions firsthand and to fathom the effect on the human spirit of living under the constant threat of annihilation, I set out for the DMZ on Wednesday, February 28, when, at a long table flanked by flags and diplomats, South Korea’s foreign minister, Cho Tae-yul, and Antony Blinken, the U.S. secretary of state, promised watertight responses to what Cho described as “North Korea’s increasingly provocative rhetoric and actions that violate multiple U.N. Security Council resolutions,” such as its military exports to aid Russia’s war on Ukraine. (In the interest of fairness, I had better now quote a headline of Thursday, February 29: white house refuses to comment on whether korea should send artillery shells to ukraine.)

For those lazybones who prefer “executive summaries,” let me now opine that although joint U.S.–South Korean war games were in the month of March twice as frequent and qualitatively more frenetic than they had been in the previous year—during my visit, Operation Freedom Shield 24 much irritated the North—and although the communiqués from the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (DPRK) bristled with hostile excellence, even as artillery fire continued to disturb disputed sectors of the Yellow Sea, all of these incidents were performances. Does intimidation deter war or precipitate it? Ask a diplomat or a weatherman. If you seek a more apodictic answer, I refer you to Newton’s first law of international misunderstandings: for every performance, there is an opposite and would-be-equalizing counterperformance.

You see, the Republic of Korea (ROK), whose citizens kept assuring me that “we in the South have more to lose”—for under their system they have somehow managed not to starve to death by the millions—issued statements that were more aggrieved, more defensively, wearily wary than bellicose, never mind their continuing blasting of K-pop and balloon deliveries (sorry, I mean “hostile propaganda” 1) into enemy land. For the DPRK’s part, as it seemed to my ROK-based interviewees, Kim Jong-un hesitated to launch a war that both sides would lose if it turned nuclear.

“Ultimately,” proposed a recent publication of Korean Odyssey Press,

North Korea’s provocations will likely continue until the regime successfully miniaturizes a nuclear warhead and can pose a credible threat of a preemptive strike on the U.S. mainland.

The threat was already credible enough, even if not to most of my hometown friends, who had better things to do than “follow the news.” The DPRK defectors I interviewed consistently expressed the belief that Kim Jong-un would be a very early casualty of any all-out conflict—and that he knew it. In short, he would push the button only if he felt sufficiently doomed and bitter to take out a few million people with him. I wondered whether such military demonstrations as Freedom Shield 24, if escalated with appropriate arrogance and stupidity, would steer him toward such a radiant course. But without them, would his vicious boldness increase? As for that other tactic called flattery, might that—however temporarily—pacify what President Clinton once termed “the scariest place on earth,” the Demilitarized Zone (what a misnomer!) between North and South?

I say “temporarily,” for my informants’ opinions were invariable: What leverage would Kim Jong-un still possess if he renounced his atomic weapons? Consider Libya. “Persuaded” by the United States into giving up his weapons of mass destruction, Qaddafi was rewarded by being sodomized with a bayonet, after which our then secretary of state, Hillary Clinton, sunnily paraphrased Julius Caesar: “We came, we saw, he died.” Hence Kim has armored his own rear end with nuclear deterrence—wouldn’t you? Which necessarily encouraged the neighbors to step into their own radioactive undergarments. After the so-called Comprehensive Military Agreement of 2018 between the two Koreas perished from a predictably lethal case of acrimony, the Washington Declaration of 2023 proposed to “manage conventional-nuclear integration” by means of the United States’ increasing the conspicuousness of its “extended deterrence”—in other words, sending “strategic assets” (spies and military vessels, I’ll bet) to the Korean Peninsula—while our ally, President Yoon Suk-yeol, sweetly refrained, as one pundit put it, from “pursuing an indigenous nuclear capability, at least for the present.” But if Kim Jong-un could retain and perhaps even enlarge his atomic arsenal, why wouldn’t President Yoon demand the right to nukes of his own—in which case, how could anyone refuse poor Japan the right to burnish its defenses?

By now you must surely realize that not one of us means any harm—no human ever has! We merely seek “security.” Wasn’t that why Cain had to kill Abel?

Among other inspired bequests to humanity, Cain invented deterrence, which was prudent of him, given that his raw intel on Abel ran: you never can tell. Hence the politico-strategic outlet 38 North assures us:

while another Korean War seems unlikely, North Korean rhetoric continues to push the envelope. The ROK and the U.S. must, and surely will, continue to prepare for the nightmare scenario.

Hurrah, hurray!

Once the 38th parallel (“recommended,” so I read, “by two U.S. Army colonels . . . using a National Geographic map in the middle of the night”) proved too straight and simple to divide the peninsula, the belligerents in the Korean War liquidated half a million or a million or more two-legged military impediments, incidentally slaughtering a million or more civilians on each side. Of course, nobody was satisfied with the armistice of 1953, but some think-tank soldier somewhere might have taken pride in all the zealous pushing, pulling, entrenching, walling, razing, and shelling of the border into a complexity perfectly suited to our entropically evil world.

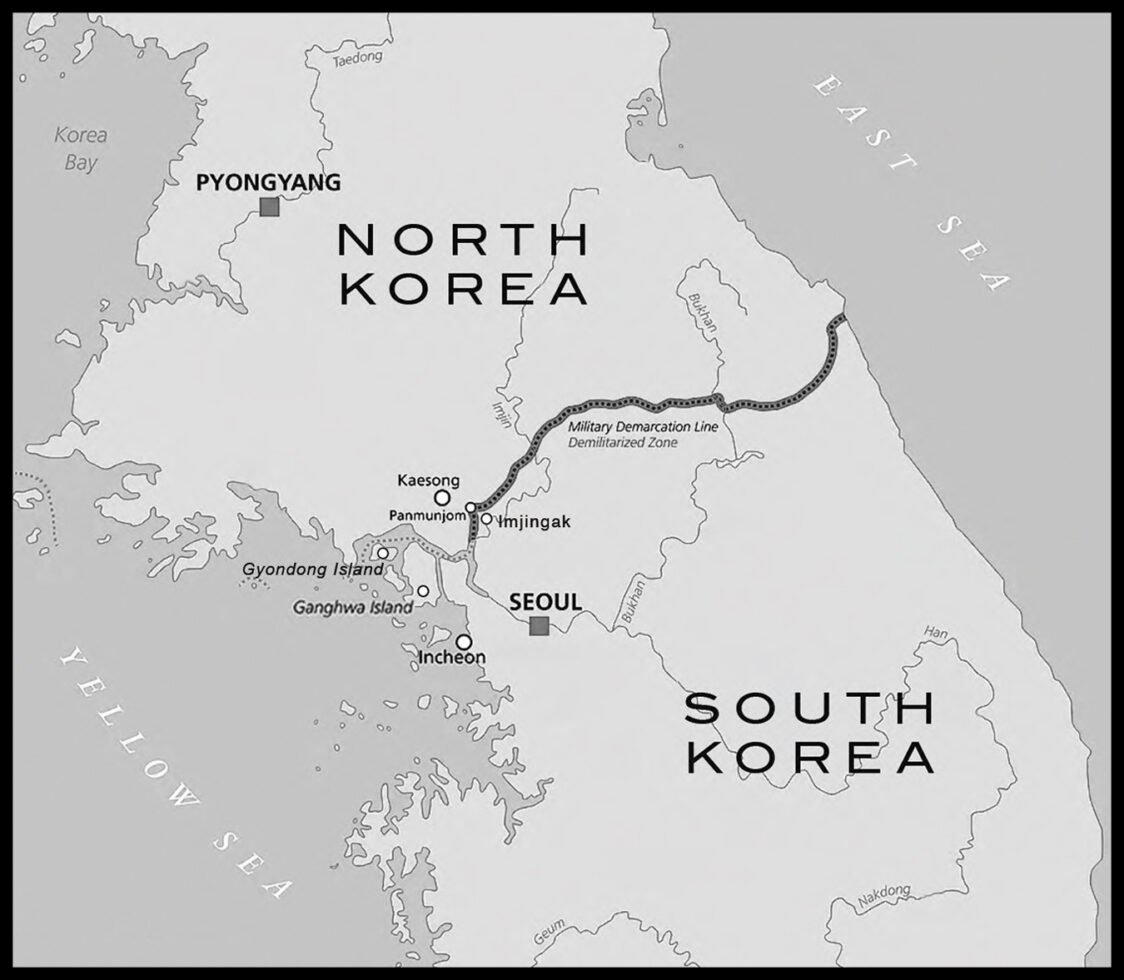

Let me now lay out for you the way the four-kilometer-wide DMZ grows out of the decidedly disputed Northern Limit Line, which straggles variously east, southeast, and northeast across the Yellow Sea, eventually transecting the inverted U of the inlet and sealing within the ROK, which my Periplus Travel Map, in capitalist fashion, simply calls Korea, the fence-enclosed island of Gyodong and its larger sister island of Ganghwa. Upon reaching the mainland, the DMZ veers a few kilometers north of Paju, passing within striking distance of Kaesong, that presently decrepit city in the DPRK that briefly, during the war, played host to armistice negotiations. After a quick eastward jog past the famous “truce village” of Panmunjom, south of which the northern enemy had bored its unsuccessful Third Tunnel of Aggression, the DMZ resumes its northeast course—wriggling farther across the peninsula than I managed to go—zigzagging east and northeast toward the East Sea’s waves. The DMZ runs about two hundred fifty kilometers from end to end. (Having been advised by my already weary driver-interpreter, David Joung, that the final eighty-odd kilometers offered “nothing but mountains,” I elected to halt our journey at the mostly obliterated town of Cheorwon.)

I will tell you of what I saw in Gyodong and Ganghwa. I will describe one of the villages within the DMZ. (Kaesong I can describe only by repute, although I have seen it through my binoculars.) I will take you to Disneyesque Imjingak, to Yeoncheon, but not to Panmunjom, which was closed to the public. In my expertly superficial fashion, I will follow the lead of the Ganghwa Peace Observatory, an observation deck from which visitors can peer north: “Visitors can observe North Korean territory and the North Korean way of life through powerful high-tech binoculars.” A placard there reads:

unended war: This room displays information containing the respective military strength of South and North Korea, and North Korean military provocations in chronological order.

(No doubt the other side told it differently.)

I followed the DMZ when and where I could. Sometimes I contented myself with the Civilian Control Line, south of the DMZ, which I was told was as far away as twenty kilometers and as close as five and beyond which only military personnel are ordinarily permitted. That was good enough to keep me within reach of any nightmare scenario.

ii. “even now the pain of the war has never stopped”

Kim Eui-joong was pastor of the Peace House on Ganghwa Island and chairman of the Nanjeong Peace Education Center on neighboring Gyodong. On a cold night whose local headline was colder still—foreign ministry to disband peninsula peace bureau amid nk threats—the pastor insisted on paying our bill at the crab restaurant. At his house, he offered me tea, established David in a snug back room, and put me up in his study, where, instead of counting sheep, I dipped into multilingual shelves of biblical commentaries. Before I knew it, the breakfast table was already set; only with the proverbial serpent’s cunning could I pay our way, which I did by making an offering to his church. This day’s headline, by the way, was more or less quotidian: nk leader guides artillery firing drills involving border units capable of striking “enemy’s capital.”

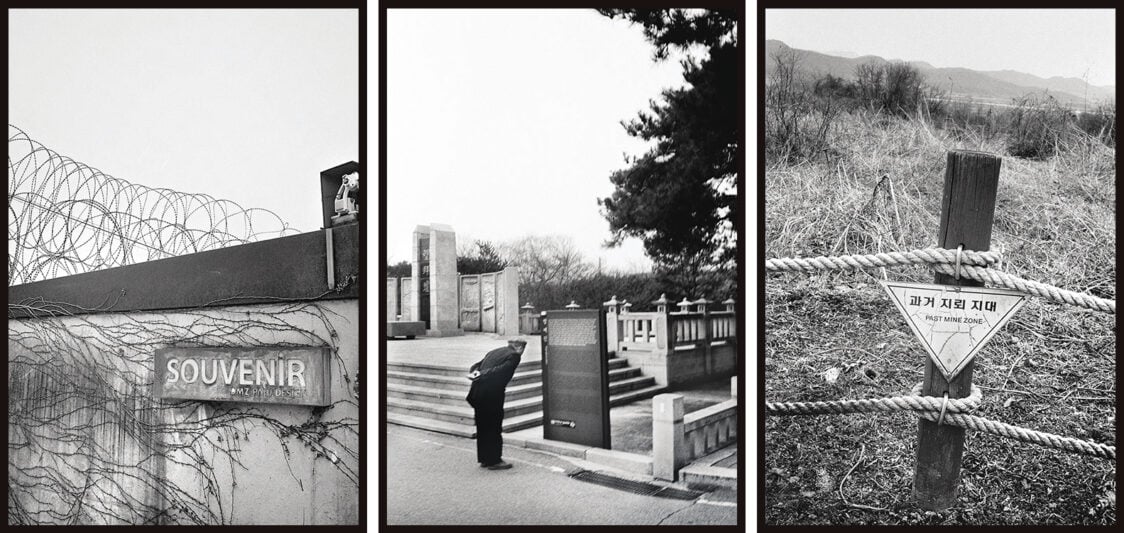

U.N. 8240 Monument to the Loyal Dead of the Eulji-Tiger Brigade, Gyodong Island

David and the pastor prayed over our pastries, cereal, and coffee before we ate. I folded the coverlets on my bed, then bowed my gratitude to the pastor’s shy wife, and off we drove, paralleling the morning sun’s reflection as it swam across straw-colored rice fields whose water grooves gleamed purple, until we arrived at the military checkpoint at the head of the inter-island bridge. “Can you see all the fences?” asked David. “Now, can you see all the land over there? North Korea.” A soldier raised the barrier, and we continued across the long Gyodong Daegyo Bridge to, yes, irregular little Gyodong, which barely escapes the touch of the westward, southwestward, and northwestward curvings of the line between the two Koreas; hence the isle’s entire circumference was as barbed-wired as David had said it would be—for please do remember Gyodong’s conspicuous proximity to utopian old North Korea. Off the bridge and up the hill of orange-brown dirt and piney hills we swung, sometimes glimpsing the North through pallid, skinny trees. Overlooking a wide and shallow inlet on the north shore stood United Nations 8240 Monument to the Loyal Dead of the Eulji-Tiger Brigade, elsewhere called the Military Achievement Monument of Commando’s Loyal Deads.

The soldiers of Unit 8240, many of whom were young men, had fought under the auspices of the U.S. Army and had received 3,875 mortuary tablets located in Daejeon National Cemetery. Sitting on a step below the altar, looking out at a row of graves whose beds were stone-enclosed hummocks of yellow grass, with the tombstones facing out toward the fence across the mud of low tide to the brownish-blue water streaks and then North Korea, I skimmed over the legend. David remarked: “The pastor says many people were killed out here by Communists, and then the villagers got angry and later killed many socialist people because of their ideology.”

When I made the mistake of asking them for an interview, the soldiers, more shocked than annoyed by our apparently unauthorized visit, impelled our departure from the monument, after which we admired the island’s perimeter here and there. We found one of the only downtown restaurants that the day’s Chinese tour groups had not entirely stripped of food; munched on spicy pork stew, seaweed soup, and kimchi; and then settled into a quiet café, where Pastor Kim told the story of his life.

“During the Japanese occupation,” he began, “my father went to China to study. He returned after the Korean liberation, in 1945, and came home a socialist. And he was very active in the socialist movement in South Korea after that.” 2 These were fruitful times for an agitator to travel around, with the masses volatile, disputatious, and sick of foreign tutelage. There was, indeed, as Communists used to say, “a world to win.”

Pastor Kim grew up on Gyodong with his mother, but his father moved to North Korea and joined the government there. When I inquired about when that would have been, he said: “I am not sure about the exact year. It was between 1947 and 1949. Then the Korean War began, and we saw many of those aligned with Communism killed on our island. My mom realized that the leftists and even their family members were being killed. So during the Korean War, she took me and my brother up to the North. My brother was seventeen years old at the time; I was four. And in the midst of the chaos of the war, my mom lost my older brother. She thought that maybe my brother would come back to our hometown, so she returned to this island with me. But as soon as she arrived, she was reported by the villagers as the wife of a Communist, and she was arrested and put in prison for two years. I had to live alone.”

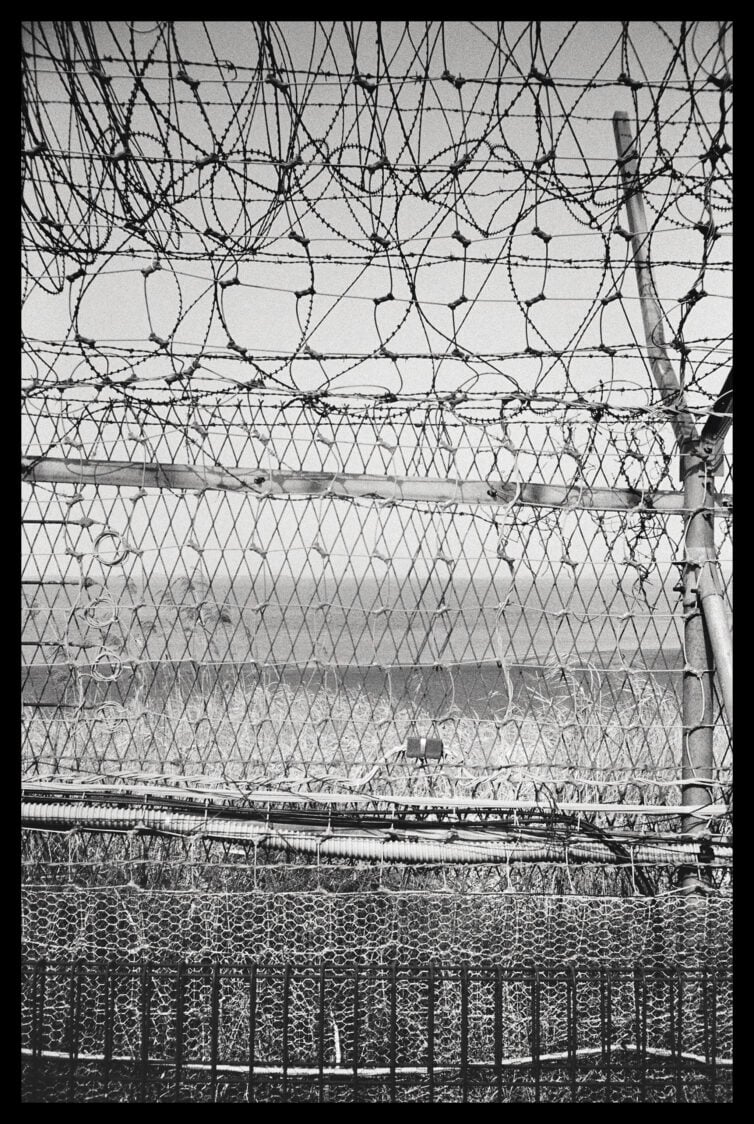

Defensive perimeter, Gyodong Island

“But, pastor, you were four or five—”

“Four years old. I couldn’t meet my brother. This is the pain of the world and the pain of the partition.”

I saw that he still grieved for this brother whom he could barely have remembered.

“How did you manage as an orphan?”

“I was left alone in my house, and one man in the village took pity on me; he gave me food. And because of that, he was beaten and killed. The right-wing people killed him. I was witness to it.”

“When your mother was in the North, did she ever have any news of your father?”

“There was no news about my father and elder brother. We became a scattered family. And my mom and I were treated as bbalgaengi, ‘Commies.’ I was persecuted as a bbalgaengi from childhood. So my mom became a Christian when I was ten years old.”

“You think otherwise she wouldn’t have cared to change her religion?”

“She was just doing it to help me. . . . If she hadn’t converted, she would have been treated as a Communist. Later, she really did become a true Christian, but the motivation to convert to Christianity was safety. I think it’s the greatest grace of God for our family that this happened.”

Sipping his coffee, he continued: “I went to Incheon for middle school. And I later realized that I was under some kind of associated punishment. After the Korean War, more than ten thousand people were experiencing associated punishment”—and here David interpolated: the so-called collective punishment, or guilt-by-association system. “If an individual’s parents or relatives were Communist,” David continued, “they were also treated as Communist. It was kind of a lifetime punishment: you could not get a good job, you could not become a public official, you could not becomea teacher, you could not become a member of the Veterans’ Association.”

“And once your mother became Christian, did the punishment stop?”

“No. In my school in Incheon, the policeman met my teacher and told them that I was a Communist. As nobody was willing to address this matter of collective punishment, people like me did not succeed in life,” he said calmly, and I could barely endure the sorrow in his eyes. “They became alcoholic and died early, except me,” he said. “At that time, I had no hope or dream, but my mom told me, ‘There’s nothing more precious than life. Aim for survival now, do not aim big.’ She told me that.”

I sat there trying to feel less of his pain so that I could do my job, but for some reason, his “do not aim big” made me feel worse.

The specter of associated punishment followed Pastor Kim for years, even into the church. Throughout his twenties and thirties, he was forced to work as what he called a “shadow pastor,” concealing his background from his parishioners. But in 1981, the guilt-by-association system was abolished. Then he finally became a Christian in his heart. And by 2005, he was able to reunite with some family members.

“Miraculously,” he said, “my mom lived past one hundred! God answered my prayer. In 2005, when she was one hundred and I was sixty, President Roh Moo-hyun told the Red Cross to help families that had been separated and under associated punishment. At that time, my mom sent a letter to the North, to find her family. And we got a letter from North Korea that they found my brother! They also found my father, or rather, his records, because he had already died. The records say that in 1951 he participated in the Korean War as a general. I was sixty years old when I received that news of my father.”

Meaning to say something consoling, I asked: “And so he had great success in North Korea, right?”

“Yes, you could say that,” Pastor Kim said. “We found that my brother had died two years earlier. But we found his children: five nieces and nephews. We met those people. It’s a miracle my mom lived long enough to apply to send that letter to the North. Because of her, we met again.”

“Did your brother have a good life?”

“I heard that my brother lived well.”

“Yeah, he was the son of a general, so—”

“But they didn’t know each other.”

That hurt to hear, although it would not have been literally true if his brother had been seventeen when they were separated.

“Was your father killed in battle, then?”

“I have no idea how he died. So that’s the end of my family story. And my mom died when she was one hundred and four years old.”

“What did you think about your nieces and nephews, your brother’s children, that you met in North Korea?”

“I could not say anything, I was so moved. Then we realized that it was both the first time and the last time we would ever see each other. Even now the pain of the war has never stopped.”

Ganghwa Peace Observatory, Ganghwa Island

iii. “the defector’s story

And now, having picked at a few South Korean war scars, let us imagine ourselves back in the Olympian situation of the Ganghwa Peace Observatory. Why not peer into the North? We are maybe a quarter hour’s drive from the guesthouse of Pastor Kim and his gentle wife. This time we had better not descend on them for breakfast and sad stories. On their island’s northernmost edge, not far past Gyosan Church, the island’s first house of Christian worship, stands the museumish multistory edifice that, promises a pamphlet, “allows visitors to observe the North Korean territory and aspects of the North Korean way of life at the closest possible distance,” as if in some ultra-authentic habitat in a human zoo.

As for me, I tried to educate myself about the North Korean way of life by interviewing defectors, one of whose accounts follows here.

In 1998, the last year of the Arduous March—a period of severe famine coupled with economic crisis—researchers at Ewha Woman’s University reported that, of 137 North Korean defectors tested, 62.8 percent suffered from diseases such as hepatitis, tuberculosis, or gastritis. Around that time, Pyongyang’s average food ration of an estimated 100–230 grams of rice per day fell short of even the Japanese occupation’s cruel 419-gram per diem.

None of the defectors whom I met looked malnourished. Perhaps, like Pastor Kim, they were malnourished in hidden ways. Possibly I did not understand what to look for.

Kang Chol-hwan, born in Pyongyang in 1968, was taken into custody in 1977, and released shortly before the fall of the Berlin Wall, not long after which he escaped to China, and then to the South. He is now associated with the North Korea Strategy Center, which, according to my interpreter, Ahlim Kim, “is doing information delivery to North Korea”—with or without balloons, I wonder—“and also doing research about North Korea.” I found him slender, slow-moving, and somehow withdrawn. My guidebook describes his 2001 memoir, The Aquariums of Pyongyang, as the “harrowing tale of a defector who survived a decade in the notorious Yodok,” a political prison camp. Since his book was unavailable to me, Kang had to recapitulate what I should already have known. But he was polite enough for that, and patient; at Yodok he must have been thoroughly educated in those qualities. It was rush hour, and Ahlim, who had been my babysitter all day, looked tired; I myself had begun to contemplate beer, dinner, and a sleeping pill, while Kang sat awaiting my opening foray into his brain with journalistic chopsticks; soon I’d pinch out a few meaty horrors so that you and I could both feel sorry for Korea the next time one side or the other let loose an artillery barrage. I had not suspected how ghastly Pastor Kim’s autobiography was going to be; but in Kang’s case, well, let’s say I had a premonition.

“Why were you arrested?”

“Because my grandfather was against the regime,” Kang said wearily. His family, which was of Korean and Japanese descent and originally belonged to the country’s upper class, had lived well—until his grandfather, a high-ranking party member, privately criticized Kim Il-sung for choosing his son, Kim Jong-il, as his successor.

“I see. And when you were sent to the prison camp, were you separated?”

“The family was all together.”

“Can you tell me what it looked like, and what happened?”

“It was really horrible, just like the Auschwitz concentration camp.”

Even when he gestured with his hands, he stayed fairly still. I saw dark circles under his eyes.

“Children were starving. And then people were wearing ragged clothes, and all those miserable things there—armed guards were around. It’s just like what you would see in a movie about the Japanese colonial period. Single prisoners were put into bunk beds. But families shared a single room.”

“You probably got to meet some other prisoners. Were most of the prisoners in that camp Japanese-Korean, or did they have different ideologies and ethnicities?”

“People came from different backgrounds,” he said, slowly chopping one hand against the other. “But then the prisoners were mainly those who helped the South Korean side during the war—soldiers’ families—or else they came from rich families.”

“Oh, I see.”

“And then the next group was a Japanese-Korean group. Even though many of them supported the North, they were accustomed to capitalistic culture, so North Korea thought that they contaminated the Communist system. They were often considered a threat.”

“And were you allowed to talk with all the different prisoners, or was it better to just keep to yourself and not talk to others and stay out of trouble?”

“We could engage in conversation, but we were monitored. So we could converse freely only within a circle of trust. Not just the prison camp, but the entire society is like that. You can share your honest ideas only with your trusted group.”

“How long were you kept at Yodok?”

“Nine years and eight months.”

“And did everybody in your family survive?”

“My family was rare and lucky, because many other families end up losing family members in the camp. My grandfather was transferred to another top-security prison camp. The rest of the family, however, my father and grandmother, survived in the camp, though they died after release.”

“What would you say about being in the camp for so long? How did that affect your personality?”

Staring into space, sitting still, he spread his hands, clasped them, and said, “I was lucky to have my family around, because if I had been there just by myself, it would definitely have been difficult. The trauma remains, because we witnessed public executions and bodies hanging for several days, so that the birds came and picked at them. Sometimes those assigned to farm the land where the bodies were buried would find pieces of the skulls and bones.”

“I think if I were in your situation, it would be very hard for me to trust people.”

“On the other hand, those who were in the same prison camp formed a strong community. They were those who could actually trust one another, and could talk about their lives together.”

“Right. And what did you have for food?”

“Just ingredients. All they gave us was raw corn and salt. Either we ground it and made something out of it, or else we steamed it like rice. Everybody suffered from pellagra. Life and death was a matter of whether the individual could recover from it.”

“Did your family get pellagra?”

“Everybody suffered from it. Fortunately, there were many rats in the camps. We would catch them and then bake or cook them.”

“How did you catch them?”

“There were many different ways, like using traps, or kind of hunting them. So people would, you know, hunt for snakes, frogs, worms, just to supplement their protein,” Kang said. “The first group of people who couldn’t survive were those who had been in the top rank; their bodies couldn’t recover from the pellagra simply by eating snakes and frogs.”

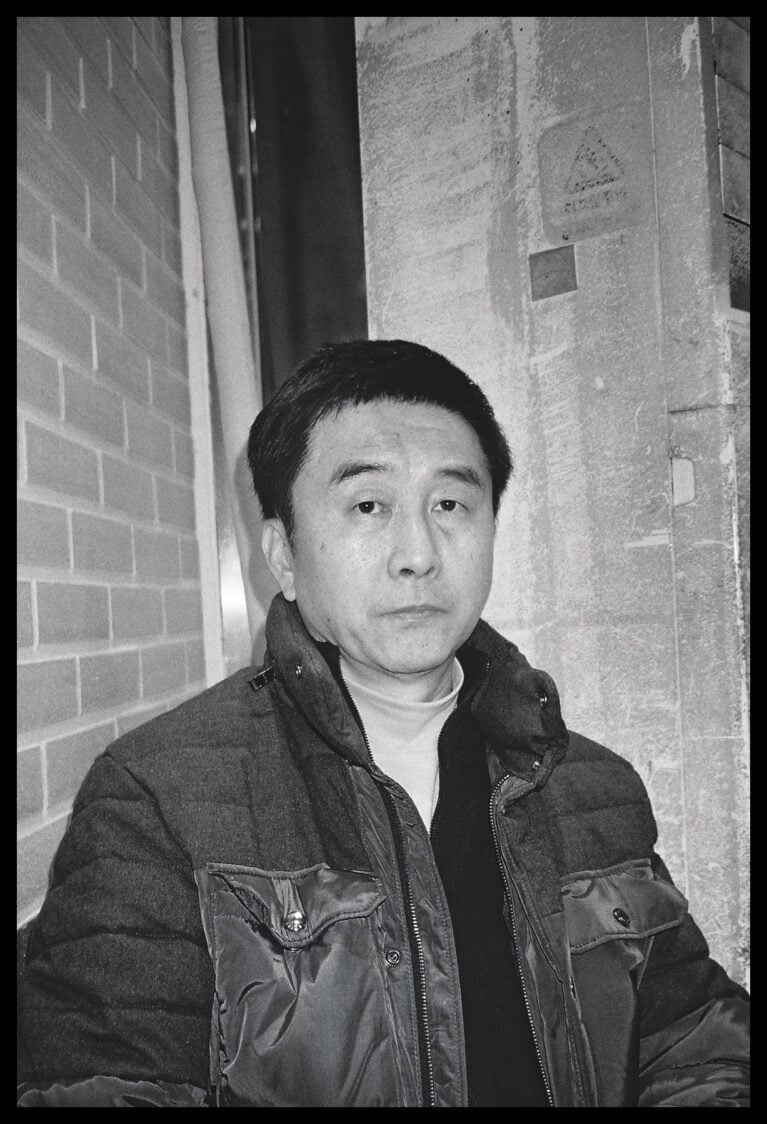

Kang Chol-hwan

“I’m sure that’s true for me,” I told him. “I’m a spoiled American. If I were in a prison camp, I’m sure I would die very quickly. Now, why were people executed in the camp?”

“The first group was the runners, the escapees who tried to leave. The second group was the resisting group, those who fought back against the guards. And the third group was those who embezzled from the food supply. And finally, those who engaged in sexual activities.”

“Sexual activities? What about in a family, as with husband and wife?”

“Dating was prohibited in the prison camp. The family was not touched. But the unmarried couples . . . ”

“Oh, I see.”

“If a younger couple were caught in any kind of romantic behavior, they would be in trouble. When a single woman became pregnant, there would sometimes be a forced abortion.”

“But would she be executed for that?”

“The woman would sometimes be punished with forced abortion, and she would be released. But then the guy, he would be moved to a more severe labor camp. The additional labor was unbearable.”

“And what would happen if a baby was born to a family?”

“It was very rare,” he answered. “But I saw a baby born, and then they were actually allowed to keep the baby. But I think that’s because all the prisoners are free laborers for the government. To keep the labor force available, the baby is kept to be raised as another laborer.”

“There must have been a lot of people who died from the cold.”

“I also myself experienced frostbite. It’s still affecting me. I saw body parts that were amputated because of frostbite. People started having inflammation and all this gangrene.”

“And then what happened to them? They probably couldn’t work, so . . . ”

“So long as a person was not dead, they would be put to work.”

“And when you were alone with your family at night, what did you talk about?”

“It was too exhausting to have a conversation at the end of the day. Everyone would just pass out. With lack of sleep, people cannot go back to work the next day.”

“And which work was the most difficult?”

“The mining. I did not work at the gold mine, but I know a friend who lost half of his face because he was hit by scaffolding. There was another job that was considered very tough. As part of North Korea’s foreign-currency earnings, they would select young workers and send them to the mountain to get valuable herbs. Usually, it was at least fifteen days’ work gathering the herbs. Often the altitude was too high to cook rice. And to survive we just ate uncooked rice.”

“That’s rough. What was the herb?”

“It’s not like herbs that you’ve probably heard of. There is something called, like, ‘crazy herb.’ Also seshin, which is a special ingredient for something like mint that kind of cools you down. And then there are some veggies that your Korea”—that is, the South—“was exporting to Japan. Yodok was deep in the mountains, a great source of all these herbs, special herbs, and then vegetables . . . ”

iv. the dmz disneyland

On the morning of March 5, I climbed into David Joung’s van and began rolling northward on the Jayu-ro, or Freedom Road. As for Freedom Shield 24, the North pronounced it so serious a provocation that an atomic war might be “triggered by a single spark.” Well, what could I do about it? Death hides in unbelievability until it rises up like a cruise missile from the other side of the wall.

According to a pamphlet, I was now embarking on a DMZ watch tour:

- Watch the Demilitarized Zone of Korea

- Aware of the North Korean strongholds

- Train the intercession and spiritual warfare

- Commune true peace and oneness

- Heal the land of war and division

It is only around fifty kilometers from Seoul to the DMZ. Those recurring threats from the North to turn “that” city into a “sea of fire” are eminently practical, but as David bitterly remarked on more than one occasion, Seoulites wasted little brainpower on border happenings. (Why should they? What could they do about the Respected Comrade’s missiles?) The landscape grew foggy and russet, interrupted by shabby buildings. Here came the first razor-wire fence. “You can see already the military facility,” David said, “but this is not the DMZ yet.” A sign announced that the truce village of Panmunjom was eleven kilometers ahead.

I had hoped to visit that locality’s so-called Joint Security Area, where North Korean soldiers stared across the gray stone threshold at the South Korean troops staring back at them, but on July 18, 2023, a U.S. soldier, Travis King—who was facing disciplinary action for possession of child pornography, and possibly for repeatedly punching a South Korean man’s face in some nightclub—had joined a civilian tour of the JSA and laughingly darted across the line. On September 27, his new friends, who initially played up his defection as disillusionment with our rotten, racist system, sent him back to us. He was promptly charged with desertion. Thanks to him, the site remained off-limits. Fortunately, David could still make me sufficiently aware of the North Korean strongholds at the DMZ Disneyland called Imjingak, which was built in 1972 and lies some five kilometers east of the border.

For South Koreans with ancestral ties to the North, the most emotionally significant object at Imjingak might well have been the Mangbaedan monument, built by their government in 1986 so that they might, as my little DMZ guidebook expressed it, “perform the ancestral rites most Koreans perform in their hometowns.” Seven rectangular panels stood tall and narrow in a semicircle behind the incense burner, each panel bearing a relief in memory of a particular North Korean province. David translated the name: mang, hyang, dan—“missing,” “hometown,” “altar.”

Several such structures ornamented the DMZ’s environs. For instance, at the Ganghwa Peace Observatory stood an outdoor Mangbaedan monument. Whenever I saw people praying there, I thought of Pastor Kim.

v. “hearts for north korea”

A soldier took my passport and kept it, but merely wrote down a few particulars of David’s ID. We were permitted to cross the Imjin River, carefully weaving between tiger-striped barriers. On the far bank, a sign proclaimed the presence of the First Infantry Division. Now Panmunjom was eight kilometers away. “This place,” David said, “is very famous for three things: beans, ginseng, and rice.” We entered a zone of muddy, snowy fields bearing occasional white cylinders of hay and ginseng whose coverings resembled solar panels. A gray-camouflage pillbox peered vacantly down at us. Two villages existed in this zone, under military control, of course. The one we were now entering was called Haemaru-chon, sometimes called “Sunrise Village.” Reestablished some twenty years ago as a “unification village,” sixty homes were built and initially set aside for families who had been displaced from this area during the war. Although former president Kim Dae-jung had laid out Haemaru such that, from above, it resembled some cross between a snail shell and a treble clef, whatever architectural elegance its design might once have possessed was soon gloomed over by a quietude only slightly less silent than that of the contaminated towns of Fukushima, Japan. Though the barbed-wire-looped fence kept it au courant.

Left to right: A kiosk at Imjingak; a man standing near the Mangbaedan monument at Imjingak; and a sign on the road near Haemaru

Before turning into Haemaru, David swung us onto a road so muddy that it took several people to push his van out of its wheel-dug rut. That was how we arrived at one of the most curious stops on our trip: the all-volunteer Link Farm, whose name referred to inter-Korean reconciliation.

Here we met Dr. Cheon Sang-man, who spoke with us while the sounds of military target practice brightened his verbs and accented his subordinate clauses. His cap read black yak. Although he had lived in Paju for six years, nowadays he commuted from Seoul, for his family’s sake: “The farmers like me from other places can stay here only during the daytime. I cannot sleep here. I arrive at nine o’clock, so around half past eight is when we cross the bridge, and about four or five o’clock, before sunset, we go back home.”

I shook hands with some of the other volunteers.

“How do you think you can help?”

“The main problem with North Korea right now is its food shortage. Agricultural cooperation would be important. But of course the North Korean government doesn’t like that. The per capita GDP in South Korea is around thirty-five thousand U.S. dollars, but in North Korea it is maybe fifteen hundred, about three to five percent of South Korea’s—how can it be possible for them to survive?”

Link Farm’s vision, he went on to tell me, was quasi-quixotic. Unpaid volunteers would raise crops as a didactic demonstration for their brothers and sisters on the other side of the DMZ, who would most likely remain unaware of their efforts until the DPRK collapsed, which might happen tomorrow or in none of their lifetimes. Finally I got it; it was simply that these farmers had what David liked to call “hearts for North Korea.” Link Farm was at present futile and therefore to a cynic almost ludicrous; but it just might be of practical use one day, a peace offering made more with sweat than with words. Paradoxically, the seven decades of separation might ultimately facilitate reconciliation, since most terrors and atrocities had occurred along the DMZ, which, as David habitually reiterated, was no focus of the attention of the majority, who accordingly felt homesick and heartsick for the provinces and relatives whom they honored with their Mangbaedan monument, not enraged against them.

vi. haemaru village

On our way to Haemaru, the sight of little huddles of toilers in the brownish-green fields almost made me forget that we were in the DMZ, until a sign warned that no vehicle was allowed to enter town without a residential permit. The good news was that though David did not appear to have one, he drove in just the same. Outside the town’s one eatery, I shot the breeze with some U.S. soldiers who pronounced the buffet “outstanding.” Just as well, for that was all there was.

Dr. Cheon bought us lunch. David and I sat with the farmers at a long table with a woodstove warming our backs, having filled our plates with fried mushrooms, kimchi, purple rice, and pork all mixed together according to however we had spooned it. A dead American serenaded us with one of my favorite golden oldies, “Raindrops Keep Fallin’ on My Head.” The three employees (one of whom was the proprietor’s wife) kept scrubbing tables and topping off buffet trays. In a cabinet, glass jars of dried peony fruit offered themselves for sale. Another commodity produced by the village was beans for gochujang; the beans are called jangdan, and this was formerly Jangdan County.

Park Sang-joon, originally from Ulsan, now owned the restaurant and its associated convenience store. He had finally won residency here four years ago. As he reminded me: “This area is called the Civilian Control Zone, CCZ. It has been very difficult for the common civilian to come inside this place. I wanted to come to the DMZ.”

When I asked if he could explain why, he said: “Because I expect North Korea to open someday. And when the North opens up, I will be the first to run to it.”

“Do you think that’s going to happen in your lifetime?”

“Within two years, I hope. I have heard about a report that there will be a huge mass of refugees when something happens in North Korea. So, two million, two-point-three million people might go to China and one-point-seven million might come to the South. I’ve been told that the Chinese government is already prepared for that. As far as I know, the Korean government is not. So, when I heard that news, I thought, you know, I need to prepare for that.”

He was another of those pastors who give Christians a good name.

“What’s it like here in the nighttime?”

“After sunset, all the travelers, tourists, visitors, and farmers have to leave. Only village residents and soldiers stay. It’s kind of a comfort, freedom from all the noise and all the people after sunset. During the past seventy years, we have had few incidents. The interesting thing is that, from the day before Kim Jong-un and President Moon Jae-in had their inter-Korean summit until now, all the propaganda broadcasting has stopped. Our village used to experience continuous and ceaseless noise. The sounds were very loud twenty-four hours a day. From the North, I always heard the name of Kim Jong-un. The South usually played K-pop songs. It was always noisy in this area—so loud from each side every night that it sounded like a concert was going on.”

“Ten years ago,” Park said, “I lived outside the DMZ, but very close, in Munsan. Yes, even in Munsan, the sounds were like a loud concert. The summit was on April 27, 2018. On April 26, 2019, I moved here.”

“Can you tell me what else is different about life here, aside from the fact that it’s very quiet and very free?”

Park said, “If you go outside the DMZ, in the city and the other places, everything revolves around humans. If you’re inside the DMZ, people and nature coexist. After sunset, when all the outsiders are gone, we see wild animals such as wild pigs and deer.”

“In my experience, wild pigs can be quite dangerous.”

“It’s quite dangerous.”

vii. “all the mountains and fields were filled with blood”

Trundling toward Imjingak so that we could see sad sights en route to Yeoncheon, we sought a place to buy coffee. Along the way, I asked David what made Koreans unique. “We are very passionate and fast and competitive, but that advances our society,” he replied. “See, there’s the fence again.” We must not have been far from the Odusan Unification Observatory, with North Korea on our left, as we wheeled along the highway, attended by blue-gray mountains and gray-blue water—not unlike that seen when boating in Alaska or, for that matter, when looking across the Han River at Ganghwa Island. Here came another watchtower, this one with soldiers in it surrounded by oodles of barbed wire. We turned off toward Munsan, where Park, the proprietor of that buffet restaurant in Haemaru, retained his pastorate; then we swung onto National Route 37 and continued toward Yeoncheon.

David said, “In this place, we had lots of battles—but not around Kaesong, which was a place for negotiations. Many people were killed here.” Beyond a fence, soldiers were playing volleyball. Then came a half dozen terra-cotta-like mounds in the shape of inverted U’s that widened at the bases; each one enclosing a semicircular tunnel—for howitzers, David said, verifying the word on his cell-phone dictionary. As we passed a car dealership, he assured me: “From here, they can target military bases in North Korea. When the battle occurs, they can hit that target.”

Now he had another happy, happy place to show me. Pulling off the road, we arrived at the Ban Gong Too Sa Wi Ryong Bi (literally, “Anticommunism Warrior Memorial”), which David Englished as “6.25 Heroes’ Memorial Park Against Communism.” My sister-in-law later translated the sign to our left as follows: tombstone for anticommunist fighters of the june 25 incident. In her translation, the tombstone’s plaque read:

Here is the place where, on October 1, 1950, the North Korean People’s Army indiscriminately opened fire on anticommunist sympathizers and villagers who had become prisoners, resulting in the unjust sacrifice of hundreds of lives. Let us honor their noble sacrifices with devout hearts.

The plaque then told us where the remains were buried. The stela lists their names in Korean alphabetical order.

“In 1950, on October first,” David said, “the North Korean army slaughtered a hundred villagers.” A drooping pine, bare at its crown, had shed rust-colored needles on that cold and dreary hill. Trucks whooshed down the highway as I wondered how many monuments of this kind spread their sadness over Korean soil. And how did the sadness of this massacre, whose victims must by now have been joined by ever so many of their bereaved survivors, compare with that of all those Mangbaedan monuments whose visitors must now include children, grandchildren, and great-grandchildren sending their melancholy prayers to their forsaken hometowns in the North, where unknown great-grandchildren of their dead relatives scrape by, maybe hoping for a single egg on white rice?

“MacArthur landed at Incheon,” David was saying, “so North Koreans kidnapped intellectuals and killed many villagers when they withdrew. There were thousands of dead bodies, and all the mountains and fields were filled with blood. This place was abandoned for many years, I heard the story . . . there was, well, one story that they threw them in a well a few steps away.”

It now began raining and snowing. Amid the brownish-yellow rock and russet leaves of that atrocity, I took photographs and notes with my cold hands, wondering whether documenting this would do you or me any good. Of course I was sorry for the Koreans, both North and South. I was pretty good at feeling sorry for people I could do nothing for. In one of our chats about the Bible, I even confessed to feeling sorry for Pharaoh’s army when they drowned in the Red Sea, but David rather sternly replied that they had been just like the North Korean leadership.

may your souls rest in peace, a banner read, but what about the souls of the living? Like a ghost out of the piney ground, Pastor Kim’s words oozed up to hurt me: “Even now the pain of the war has never stopped.”

viii. some thoughts about a chimney

After crossing a tributary of the Imjin River, we turned right toward Dong-i-ri, then took a left on an unmarked road and another left, where a signpost introduced us to National Registered Cultural Heritage 408, the crematorium for battle-slain United Nations soldiers in that war which had now lasted seventy-four years. Its official name was the Crematory for U.N. Troops in Yeoncheon. Another sign converts its hypothetical past coherence into lines that (let us hope) will inspire some military engineer to rebuild it bigger and better for the next war. Meanwhile, the chimney stands almost alone, so nearly bereft of context that the flatness from which it rises could be either courtyard or campground. Polynesians used to construct lava-paved courtyards on which to found their thatch huts and temple complexes, under the watch of humanoid statues called tikis. The only tiki here is that chimney. How many corpses did it devour for the greater tidiness of the United Nations and of us others who would rather not be surprised by stinking yellow bones? Someone must have raked and weeded that strange mosaic of a floor, since instead of merely decrepit it seemed to be actively bare, like a parking lot cleared by chemical defoliant.

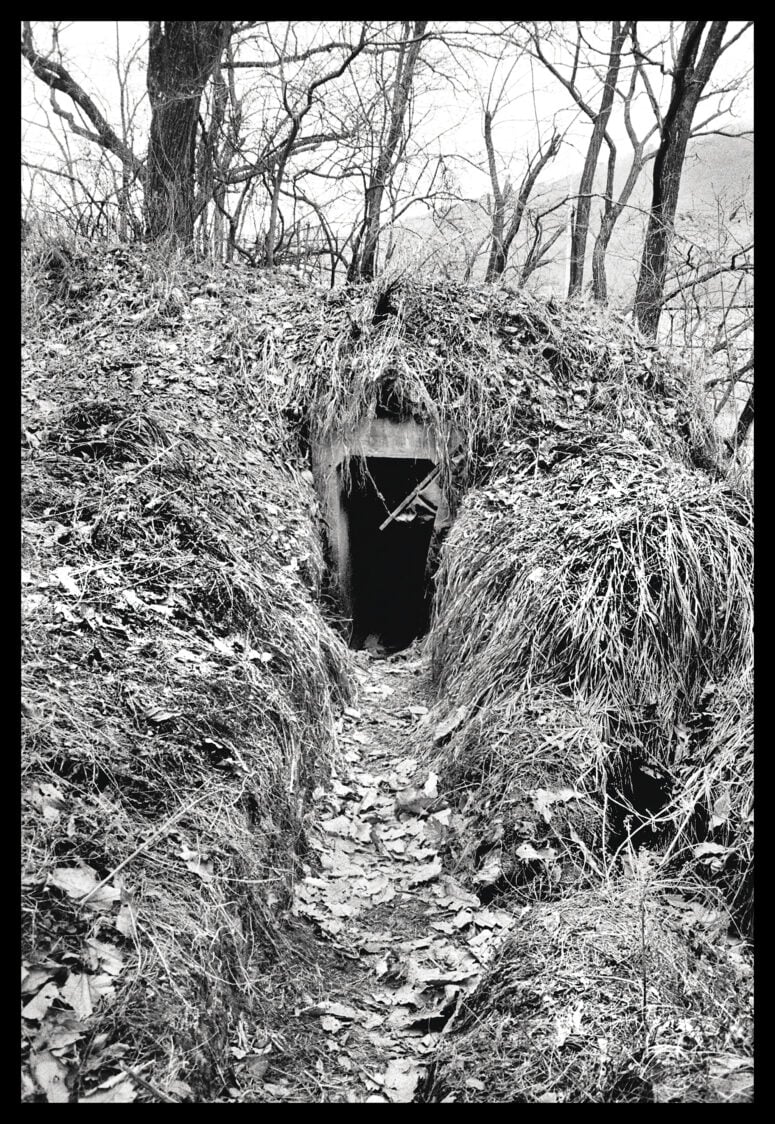

An entrance to a disused bunker near the DMZ

Although the foundations of rooms remained, like lines of an architectural drawing expressed by pebbles laid end to end, only the chimney still loomed against that hill of dead leaves and leafless trees, while traffic soughed indifferently below. David said that the builders had used whatever stones they could find; hence the yellowish cherts, grayish flints, and brownish rocks, all of which I now remember as smaller than they possibly could have been. Sleet sped down and down like time itself, temporarily sparkling on the barren, pallid surface of those meaningless pebble walls whose relics lingered as broken corners and whose charred slabs were textured like fossilized crocodile skin, while the dark trees drooped, their branches spreading like an unconscious drunk’s fingers slowly, slowly letting go of some woman’s unkempt hair.

ix. typhoon observatory

But why gaze mopishly down at the ground where black blood and ashes alike have become dust, when one could take a more forward-looking view at the Typhoon Observatory, which David had advised me would best show the opposing military’s installations? As one sign put it, from here on, it’s civilian access control area. No photographs of the view were allowed, but it was snowy and foggy anyhow.

Looking southwest, I saw slanting snow squalls speeding down across the ridgeline; I remember brick walls topped with stone. On the north side, snowdrifts were gathering and thickening like lakes; then I tilted my gaze down the hill to a forked ditch filled with dark water or ice and the dead grass; a series of steps paralleled the wall, whose Y-shaped uprights supported two heavy-looking horizontal crossbeams and were then crowned with squiggles of barbed wire resembling an unraveling sweater.

After speaking with a chatty soldier who told me that the front line was pretty inactive and had been for some time, I collected David, and down we drove, back into the free world of fallow rice fields, covered rows of ginseng, aluminum sheds, and empty pavement shining in the rain. The hamlets we passed had a rural-industrial look not unlike the countryside in Oklahoma or West Virginia. Every now and then, we were treated to the drama of a creeping, blinking tractor. We entered Yeoncheon, because even journalistic war ghouls need lunch.

x. “more dangerous than before”

An orderly brought snacks and coffee that we did not touch. I promised to keep the interview short, in deference to the continuing Freedom Shield exercises. Opening my laptop, I asked what I hoped a military man could answer: “How dangerous would you say the tensions are right now between the two Koreas?”

Slowly, fluently gesturing with his left hand, the gray-haired, bespectacled colonel, Park Heung-jae, whom I considered almost gentle-looking (after all, he was a chaplain: to be specific, the chief of chaplains for what David, in noble Roman style, called the “Fifth Legion”), explained the situation. “More dangerous than before. Kim Jong-un and Kim Yo-jong have stated before that they consider us an enemy, and that they would attack us.”

“How much worse has it become, and since when has it gotten worse? The past year? The past five years?”

“In terms of the degree of tension, civilians and military people are different. Because South Korean civilians have been living this way for many years, now they feel peaceful. But in the military, it’s our duty to protect the freedom of this country, so we have a higher level of alertness than civilians.”

“On a scale of one to ten, if one is peaceful and almost friendly and ten is there’s going to be a war in five minutes, where would you put the border situation?”

“From the perspective of the military, we are still engaged in a war. We never stopped, because we didn’t declare an end to the war . . . there is a chance that it will start again at any time. The possibility is more than five, from the military’s perspective. Sometimes seven, sometimes eight.”

“Civilians have been telling me that North Koreans know they can’t win,” I said, “so they only want provocation to get money or respect or something like nuclear recognition.”

“Civilians feel that way,” said the colonel in his gray-camouflage uniform, “but we have been considering the motives that might lead the North Koreans to war. One possibility, we think, is that the North Korean regime is having internal issues.”

“But North Korea cannot win, right? Even if they destroyed South Korea in a nuclear war, the fallout would kill them.”

“They cannot win,” said Colonel Park. “We have not only our military ability, but we also have a strong alliance with the United States.”

That sounded like suicide for North Korea, and indeed the colonel now continued: “It’s suicide.”

“They have less to lose.”

“Yeah. They don’t have much to lose,” David added.

xI. homeland security

At noon on the previous day in Yeoncheon, while David made call after call on his cell phone at the Mom’s Touch fast-food chain he favored (when I paid, he earned points on his loyalty card), I sat staring out the window, the center of which was occluded by a glowing image of two towering cylinders of crunchy fried-chicken sandwiches topped with lettuce and raw onions. The world outside consisted of falling snow, parked cars, a heap of tires at the Hankook shop, a passing truck whose bed was vinyl-lined. To complete the towering ugliness, Mom’s Touch’s inset ceiling lights reflected themselves in the gray sky like yellow UFOs. Well, well: it might not have been freedom’s fault that its works were so often ugly, and I’d much rather be here than eating worms and snakes in the Yodok concentration camp or walking past starved corpses day after day.

Later on, as I sit at Incheon’s shiny airport revising this scene, with gifts for my friends in my luggage and one of my favorite songs playing over and over in my headphones, expecting nothing worse than a delayed flight or a little special treatment from the occasional suitcase slitters of Homeland Security, I remember the previous night’s joy-making sizzle, over snow-white charcoal, of five-layer pork belly that was lovingly chopsticked into my steel bowl by my brother-in-law, who keeps my cup eternally filled with soju as we gossip about the family. Because I paid for dinner he buys our higher-proof stuff at the upstairs bar in the alley whose clients are so young that even his just-married thirtyish daughter, who in American bars gets carded all the time, would in his opinion feel old here. As we finish the bottle, we remember our good old nights of marathon drinking with pretty girls. He keeps me company as far as my subway stop, and then around the corner from my hotel I order an extra-dark and foamy cacao milk, watching happy couples hurry down the sidewalk beneath the business towers’ glowing hangul characters. I love this world!

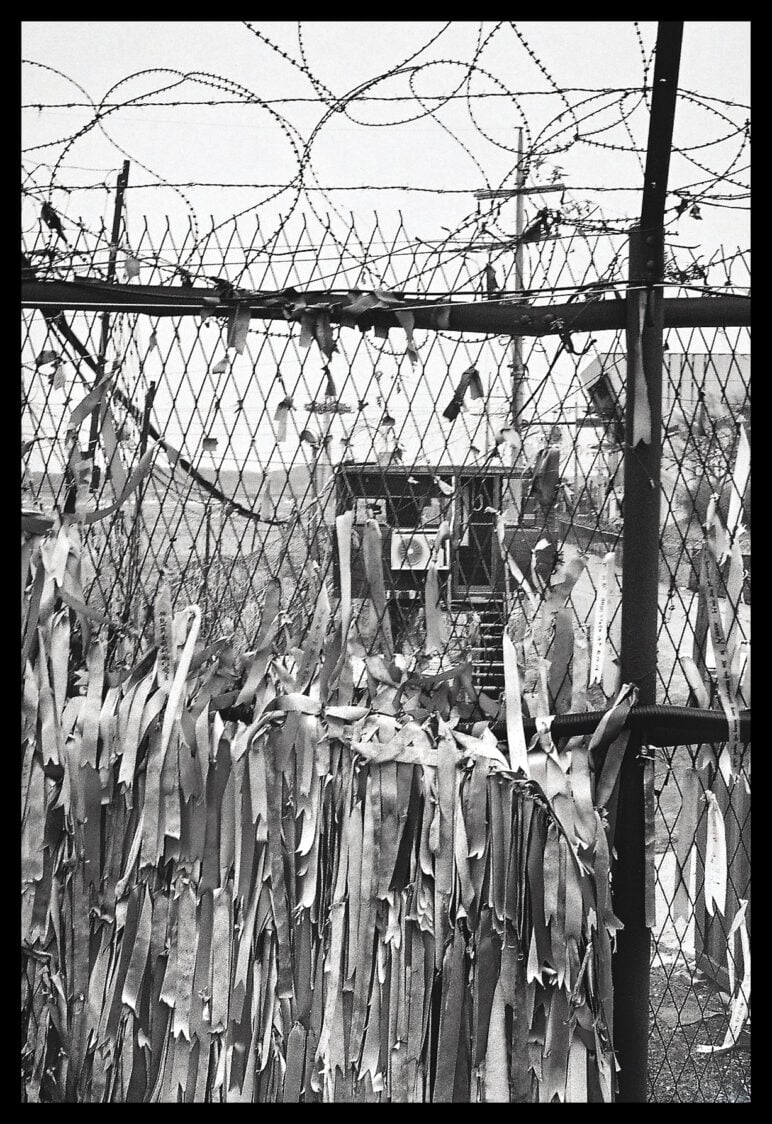

Peace ribbons near the Freedom Bridge in Imjingak

My brother-in-law, who runs a small factory, often talks about how wonderful capitalism is. When he says this, I clink cups with him and think: “What do I know?” I despise the capitalist selfishness that goes on ruining our planet. But I needn’t worry about getting executed because some relative ran away.

Maybe there would be no war. Or maybe Kim Jong-un would step up his bombardments of the Yellow Sea. Maybe, as one rumor I heard went, Kim would sell some of his soldiers to Putin to fight in Ukraine. Maybe he would get cornered into pushing the red button—and then, for Pastor Kim Eui-joong and millions of others, the pain of war would finally stop.

The author wishes to thank his brother-in-law, Shin-Jong Ryu.