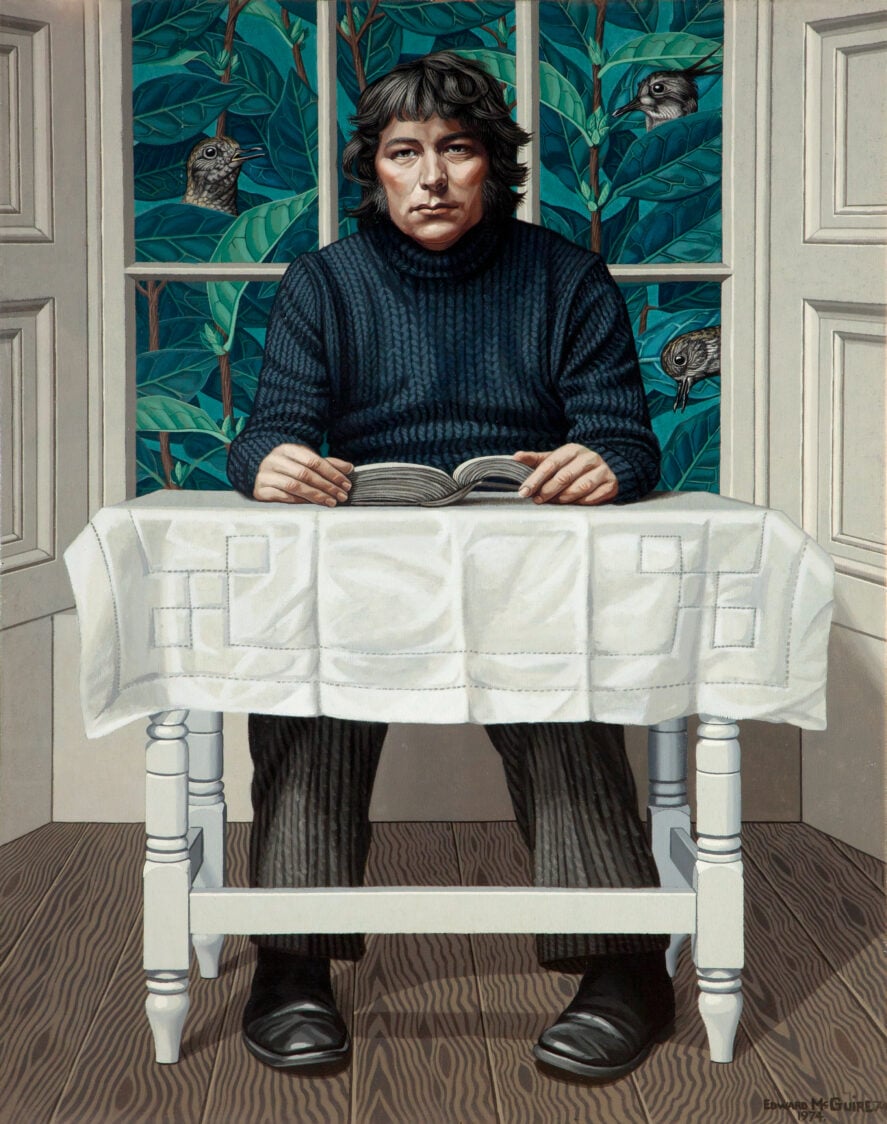

Portrait of Seamus Heaney, 1974, by Edward McGuire © National Museums NI, Holywood, Northern Ireland

Discussed in this essay:

The Letters of Seamus Heaney, edited by Christopher Reid. Farrar, Straus and Giroux. 848 pages. $45.

This buoyant anvil of a book has brought me to the edge of a nervous breakdown. Night after night I’m waking with Seamus Heaney sizzling through—not me, exactly, but the me I was thirty-four years ago when I first read him, in a one-windowed, mold-walled studio in Seattle, when night after night I woke with another current (is it another current?) sizzling through my circuits: ambition. Not ambition to succeed on the world’s terms (though that asserted its own maddening static) but ambition to find forms for the seethe of rage, remembrance, and wild vitality that seemed, unaccountably, like sound inside me, demanding language but prelinguistic, somehow. I felt imprisoned by these vague but stabbing haunt-songs that were, I sensed, my only means of freedom.

And then I read Heaney, specifically his first book, Death of a Naturalist, which he’d written, it seemed obvious to me, out of the same tangle of mute, inchoate pain and free-singing elation: “The plash and gurgle of the sour-breathed milk, / the pat and slap of small spades on wet lumps.” John of Patmos gets an angel to break his brain open. My own rapture required merely a table set with sonic objects. Butter, Heaney means in that last line, though you feel the words themselves are also the subject, rendered stark and palpable and ungainsayable from the linguistic “churn” of the poem (“Churning Day”).

But pain? The poem’s about churning butter, for God’s sake. But the pain has to do with coming to consciousness, that huge first heave a young poet must make from sensation to representation, and the further and even harder heave to solder a seam between them with a singular sound. At twenty-three, I sensed, even among the bucolic subject matter, that Heaney had gone through what I was going through, and there are plenty of passages in these letters that confirm my early instinct. “It is about the artist and his relation to society,” he writes to the painter Barrie Cooke in 1985, nominally about Sophocles’ Philoctetes but transparently personal. “His right to his wound, his solitude, his resentment. Yet society’s right (?) to his gift, his bow, his commitment to the group.” Heaney is speaking of political obligations, but to make the transition I’m referring to—to translate one’s inner imperative into a form that can be shared—is, no matter how private the writer, a “commitment to the group.” The success Heaney had at negotiating this tension was a fortifying example.

I didn’t grow up right down in the clop and clabber as Heaney did, but I was, you might say, chicken-shit-adjacent. We lived in a small West Texas town where farming and ranching still had a natural purchase on people, and enough of my childhood was spent among hay bales and hayseeds that Heaney’s milieu seemed mine. The ferocity of need and nerves a young writer brings to his models makes “influence” seem too weak a word. I metabolized Heaney, the only living poet who has ever had such a claim on me. (There have been several dead ones.) One can come to resent such possession. One can develop a keen eye for the weaknesses in the work, can find oneself scouring interviews and essays for chinks in that armor of authority. I think that may have played a part in my willingness to read through eight hundred pages of The Letters of Seamus Heaney, may even be part of what has so unsettled me. Not that I’ve discovered chinks; quite the opposite, in fact. The man seems unassailable.

A “collected letters” already seems like an anachronism. But yes, little Johnny, human beings really did once get down on their knees every afternoon beside a mail slot, waiting for some transfiguring love or luck to slide through. Well, at least one young man did. Most young poets face at least ten years of writing in the dark: impossible to publish poems in magazines, never mind a whole book. Add a few demeaning jobs, patronizing older poets, relatives wondering what the hell you’re doing with your life, and letters become the only way of managing the mismatch between the Everest of your ambition and the Sahara of your circumstance. For many, they become a crucial part of one’s creative work and are both prelude and key to everything that follows.

Heaney’s early letters are a disappointment in this regard. He had success too early and completely for letters to have been creatively important, and he was born with decorum. (“The po-faced and solemn-eyed altar boy aspect of my make-up,” as he writes here.) The letters my friends and I exchanged in our twenties were Roman-arena affairs, ids and egos going off like misfired fireworks, redwood reputations felled with our mighty pens. (And metaphors mixed with abandon.) That’s not to suggest that they weren’t serious, and seriously useful to our development. Beyond the emotional tracer fire—an obvious and no doubt now-embarrassing venting of envy and constraint—we argued aesthetics, filed our poems against each other’s whetstone tastes, and encouraged and consoled each other.

These were the letters I most anticipated from Heaney, vestiges of a time before the public mask had affixed itself to him. But there’s nothing—no backbiting, no meanness (of either sort), no catty contempt for the hands that fed him, not even a stray complaint about some hack winning a prize. They’re not boring, exactly. Heaney’s linguistic gift was prodigious, and he almost couldn’t help himself from estranging and enlivening scraps of language here and there. And yet they’re boring. I was a hundred pages in before I made a note on the text.

And then, gradually, they improve. It’s as if the normal process were reversed in Heaney, and letters became more important as he became more frozen in fame. You find yourself envious of his writer friends, whose work he responds to with praise that’s too precise to have come easily, but also suggests some personal fulfillment. “The way your poems backfire and resume the energies of their predecessors wakens the love of poetry in me like nobody else’s,” he writes to Ted Hughes (whose work seems to have had a similar effect on Heaney as Heaney’s had on me). There are letters of sympathy here that are so beautiful, so lit with precision of remembrance and love, that you forget they’re coming from a Nobel poet so overborne with requests and responsibilities that half the time they’re being composed on planes. By the time I turned the last page—“Noli timere” is his final, famous text message to his wife from his hospital bed—I threw up my hands and gave in: this man was a saint.

I do believe this (a saint among writers, I mean, whose criteria for canonization are modest), even as I don’t quite trust this collection as definitive evidence. Heaney’s family prohibited their letters from being included, which seems perfectly understandable. But Christopher Reid, the book’s editor, was a friend of the poet, and I can’t help wondering what has been omitted or excised. There are many editorial ellipses in the letters. Sometimes Reid explains his decision (repetitions, logistical detail, etc.), and sometimes, often at suggestive moments, he doesn’t. Is Heaney being protected? If so, from what?

The publication of The Field Day Anthology of Irish Writing in 1991 would have been a monumental event in Irish literary history no matter what, but the criticism of its lack of women editors and its paucity of women writers created a firestorm. Heaney, as one of the editors, was in the middle of this and obviously disturbed (and regretful), but the traces of this event in his letters are meager. “I am more alive than before to the immense rage which man-speak, or even men speaking, now produces,” he writes to the sympathetic ear of Hughes. “The historical tide is running against almost every anchor I can throw towards what I took to be the holding places.” The quote is followed by one of those mysterious, unexplained ellipses that can’t help but raise suspicions.

Heaney would have been a major poet no matter what, but America turbocharged his career. An early year at Berkeley opened him to the energy and excesses of the West; later years at Harvard to the aristocrats and orthodoxies of the East. He thrived in both. For much of his adult life, he was troubadouring the country (and the world) at a pace that seems, to this poet, crushing. This continued, even increased, long past the point when there was any monetary need, and though he’s constantly lamenting that “the chance to sit at a desk has almost disappeared from my life.” Fame is a poison. For everyone, I think, which is one reason this country seems paralyzed in a kind of collective writhe: social media gives a dram of fame to all. It takes a hardy soul to remain a soul with one eye on this demanding hologram. Heaney seems to have been one. He was at ease with praise, partly because he retained his unease with it. (“I have this deplorable shyness or self-deflecting habit when it comes to reading things that are in praise. I suppose it is a caution, but it ends up as a boorishness.”)

And what praise there was. It had to have been maddening to his Irish friends when even his weaker books garnered awards. (“Pompous ass,” Derek Mahon scribbles under a note of rare autopilot praise from Heaney.) And not just his friends. I recall seeing in the late Aughts a report showing that Heaney accounted for some preposterous percentage—perhaps two thirds—of poetry sold in the United Kingdom. Heaney himself grew circumspect, and in later years you find him preempting an honorary degree, genuinely lamenting that a prize hadn’t gone to someone else, and—this is somewhat comical—taking care to make a critic more critical. You know the praise has been excessive when even the subject starts applying the brakes.

America must have been in part a refuge. His Irishness and his affability immunized Heaney from the more trivial and toxic elements of our literary culture.1 His letters do suggest he kept a wary eye. In 1988, he wonders about the effects of teaching the “acquisitive brilliant young of Bush-ville” and drowning in “the querulous self-salving rhetorics of the million books of useless poetry.” Twenty-five years later, at the annual Association of Writers and Writing Programs conference—shocking affairs, these gatherings, a cross between a throng of fasted pilgrims and a city-size ball of mating water moccasins—he marvels both at the huge horde and “the bewilderment the aspiring young must experience in the writing realm.” (There’s another unexplained ellipsis here.) How I envied Heaney his tiny Ireland, with its living link to a deep past, its coherent but unsiloed literary culture (connected to the general culture, I mean), its freedom from the “bewilderment” of styles, stances, and fashions facing young American poets. I know, I know: energy, heterogeneity, experiment, and all that. America produced the fuel that rocketed modernism. But for a young poet, Ireland just seemed so much more manageable.

Heaney’s work weakened as he aged. (I once combed The Spirit Level—triumphantly? pathetically?—circling the clichés: “bone-dry,” “sky high,” “hard as nails.”) There are still flashes of the old intuition, and I’d take late Heaney over 99 percent of what’s published. But still. Much of Heaney’s work had relaxed into notations rather than culminations of experience. Most formally inclined poets come to “discover” a more relaxed style, just as most people come to find walking much more amenable than the wind sprints of their youth.

The letters don’t suggest he was aware of a decline—a grace given to most of us—but one of the endearing things about them are the lapses of confidence he confides to friends. Post-Nobel, he admits to a “panic attack” over a (for him) modest assignment, and throughout his life he clearly relied on friends’ responses to his work. They weren’t trading truth serums. Heaney lavishly praises some mediocre works (Birthday Letters! maybe the worst book ever published by a great poet) and is constantly delighting and demurring at reciprocal strokings. There’s no shame in this. Poems included with a letter are rarely an invitation for honesty. (And a book, in my experience, never is.) Affection trumps aesthetics, probably always, but one becomes more conscious of this with age. Any vestige of that swashbuckling critical confidence is likely to lead to—the worst book ever published?—second thoughts.

No, it’s mostly consolation old poets offer each other, for there is an aboriginal loneliness in a life of poetry. In some sense, it’s what determines a life of poetry. And sometimes even the flares from other lonely encampments are insufficient. “Some day I will tell you how much your letter means/meant to me,” Heaney writes to Eamon Duffy in 2010. “Just now I have been/am going through a period—my first ever—of shaken confidence and endeavoring to screw the courage to the sticking point.”

My first ever. I paused for a long time here. “Shaken confidence” is what he says, but what he means, as other letters clarify, is depression, which he’s tasting for the first time at seventy-one. How is it possible a poet could be at once so touched with that primal fire that shapes, scalds, and even incinerates so many true poets, and at the same time so adjusted to, so obviously in love with, plain old hangdog life? In his late book of overkill interviews with Dennis O’Driscoll, Stepping Stones, Heaney speaks approvingly of the notion that there is a “rooted normality of the major talent.” I recall pausing for a long time here, too. Dickinson? Rilke? Baudelaire? Blake? The claim seems more aspirational than accurate, maybe even defensive—the altar boy claiming his right to the transfiguring blaze. The thing is, in the case of this one weirdly well-adjusted genius, he’s right.

Heaney’s career already seems mythic. No English-language poet has enjoyed such fame since Robert Frost, and even Frost’s work didn’t have Heaney’s international reach. His closest contemporary American analogues, in terms of critical attention and status in the literary world, are John Ashbery and Glück (who won her own Nobel). But the difference is extreme. Heaney’s sales dwarf theirs, for one thing, but it’s more than that. Two U.S. presidents have reached for Heaney’s work for rhetorical ballast and vision. (There’s a wonderful letter detailing the time Bill Clinton barged into Heaney’s hospital room and charmed the whole ward.) And Heaney’s work has penetrated diverse disciplines in a way that no American poet’s could hope to.

I’ve wondered if the internet, that concentration killer, might actually aid poetry in this regard. The unit of currency is becoming the poem, rather than the book. Individual poems often ricochet around the internet and gain a significant and diverse readership, whereas even prize-winning books are invisible beyond the poetry world. This is not necessarily bad, as I say, since the individual poem is actually the unit of currency in poetry. There’s something both liberating and terrifying about the nature of poetry’s “guild.” The bar for entry is very high, but a single poem can gain you access.

I spent ten years editing Poetry, and part of my education involved learning to attend to poems, not names. Great poets will send you terrible poems. (I once rejected, with genuine sorrow but no regret, Seamus Heaney.) And great poems—great for the moment, I mean, piercing and refreshing reality in some surprising way—can come from the most inauspicious people and places. Heaney laments in Stepping Stones that there’s no “monster hogweed” talent sticking up out of the “great crop of ripe, waving poetry” in the United States, no single poet most people can agree is great. This would give us some focus and ballast, he feels, temper the mania of the million competing styles. Perhaps. But what if this new means of distribution is actually better for the art, brings it closer to its origins, which predate the book, of course, and ink, and even written language. There’s a striking passage in Coleridge’s notebooks in which he wonders about the effects of written language, of specifically the act of learning to read. It makes us think of words—and, inevitably, things—as “distinct component parts.” “What an immense effect it must have on our reasoning faculties!” he concludes. “Logical in opposition to real.” It’s that “real” that poetry is always trying to recover and renew.

America does make that difficult. This is a prose country. The sheer sprawl of us, the maddening sanity of our suburbs and gridded cities: prose. Our endless fever for quantity and quantifying, the blob logic of big-box stores and factory farming and Facebook: prose. The weird rabid religious compulsion to read Scripture (or the Constitution) like a branch of mathematics, this ostensible allegiance to the Word that is actually terror of it: prose, prose, prose. Even our poetry is, quite often, prose.2

America is also a psychological country. For all the religious fervor, the intellectual class (and by that I just mean people who take reading seriously) tends to be materialist. I have found this to be true even in religious settings (liberal ones, in any event), where Jesus is an exemplary moral figure and the Resurrection vaguely embarrassing. For a materialist, the most important existential activity is the realization of the self. This self is both intimate, comprising our memories and emotions, our desires and wills, and alien, in a sense, opaque, so that we talk about these things as if they were separate from us. A good life consists in integrating these constituent parts of ourselves. Even people who know nothing about psychology often operate under this assumption, and their lives are arranged toward securing and asserting a coherent self. This makes perfect sense, since if the self has an end (materialism, remember), then the self is an appropriate end in itself.

I’ve heard Whitman blamed for America’s obsession with the self, but that’s wrong. The “self” in Whitman is uppercase, a mysterious and elusive entity, composed of the grass and the stars—indeed, of other people, other “selves”—as much as the individual. It’s a fragment of eternity. (“If you want me again look for me under your boot-soles.”) American poetry’s psychological slide really begins with Robert Lowell, whose influence, even in poets who have never read him, persists.3 Lowell was always a poet of almost pure will, but the engine of his early work is sound, and sound leads to the unconscious, and the unconscious leads beyond the lowercase self. (The unconscious properly heard, I mean.) But Lowell’s subsequent work, for which he’s much better known, is a textbook example of poetry written by the psychological self. Even when he’s self-mythologizing, even when he seems to be writing about historical figures, one feels it’s all in service of this entity that even he calls “Robert Lowell.”

I’m not talking about confessionalism. The impediment is broader than that and affects work of wildly different styles and aesthetics. Ashbery’s work, for all its seeming repudiation of the psychological self, could even be seen as an expression of it. Instead of asserting some coherent self, much less the possibility of integrating it, Ashbery obliterates the entire enterprise. The “self” is exactly what “reality” is: a formless flood of matter, information, impressions, emotions, what have you, that rushes around us, and is us. An individual Ashbery poem is—or aspires to be read as—a random scoop out of the torrent. This can be exhilarating. Ashbery possessed poetic genius, and his work reveals something new about the reciprocal relation of mind and reality. But such a project, ultimately, is still in thrall to that original paradigm. A wry psychologist might even call it a “reaction formation.”

I’m also not saying that American poets need religion. Whitman wasn’t religious in any traditional sense; neither were any of the major American modernists, aside from T. S. Eliot. Nor were Gwendolyn Brooks or Elizabeth Bishop, two great poets immune to the criticism I’m making. I agree with Heaney that there isn’t an obvious towering American talent in the past fifty years or so, despite the unprecedented proliferation of vital, durable poems.4 That may be a historical accident (it happens), or it may be that the old idea of the “great poet” is simply incompatible with the way poetry exists in this culture now. But I remain suspicious of psychology and the valorization (or reactive obliteration) of the individual self. A certain diminishment of ambition has set in: poets no longer feel they can or should attempt to speak to all humans—and even, occasionally, beyond that.

And that does involve a lack of faith—faith in the poetic enterprise itself. That it can cast us into orders of experience that we couldn’t have imagined otherwise. That it’s “a surge of the soul rather than a servant of the ‘history’ or ‘society.’ ” And that it can be a fully adequate “match for reality,” a reality that can be both awful and sublime, but which in any event exceeds our understanding so completely that any mature artistic vision must come to “credit marvels.”

Those quotations are all from Heaney. Is it possible that these two qualities—music and mystery, let’s call them—account for the immense success of his poetry in America? That he didn’t simply cut against the grain of our collective consciousness, but reawakened capacities, poetic capacities, that had lain dormant?

That probably accords too neatly with my own needs and inclinations to be entirely true. What is true, though, is that Heaney, though he held and mined modern psychological beliefs about memory and the self, also carried forward an idea of poetry that is ancient. Most poets come around to the “more or less religious reach,” he writes in a 1991 letter to Anne Stevenson. This is no late embrace of Christianity (though any cradle Catholic who says “noli timere” is quoting Jesus), and it certainly isn’t an Arnoldian effort to replace religion with poetry. It’s simply the statement of someone who has been given a gift—a gift with spiritual capacities—and knows that he must not betray it. It’s especially interesting that this remark is to Stevenson, who once told me that it was incumbent on modern poets who did not believe in God to refuse any lapse into traditional religious language. Our language is rooted in our lives, and if the roots are dead, whatever blooms will have a hint of rot. New spiritual experience demands new language.

Heaney split the difference brilliantly. In the transcendent series of sonnets “Clearances,” which he wrote after his mother’s death, he deploys Catholic rituals and icons only to leap, in the final poem, beyond them. There are many such examples. But if one function of poetry is to extend the language to account for the growth of a culture’s sensibility (and the poet is responding to the culture, however inchoate or distant the signal), another is to salvage meanings from words that have become unmoored from, or distortions of, their objects. “Glimmerings are what the soul’s composed of,” Heaney writes in “Old Pewter.” The “glimmerings” here are the “blizzards” and “slither[s] / of illiteracy” that the poet’s eye (and ear) has found in an actual old plate. The soul is the same one that ancient Egyptians called the ka, or that God promises the psalmist will be rescued from Sheol, or that lay dormant in the minds of so many contemporary American readers, waiting for the right sound to set it free.

It’s a melancholy endeavor to read through a writer’s collected letters, at least those of a writer whose life and language have merged as thoroughly as they did for Heaney. The effect is much more piercing than reading a biography, which remains safely “outside.” In letters like Heaney’s, you feel just how much life there can be between the apertures of St. Bede’s mead hall. And then, closing the book, you feel a profound silence that is—for this aging poet, at least—devastating. I have found myself holding hard to those glimmerings that remain very much alive in the poems, which are stilled and belled with the very quick of existence. The poems, unlike the letters, unlike all the prose that Heaney wrote, are the cries of their own occasions, adequate to the loss they in no way elide, and to the moments of transport they neither diminish nor embellish. If, as Heaney wrote, “the end of art is peace,” this art, with its singular music and saving mystery, has attained that end.