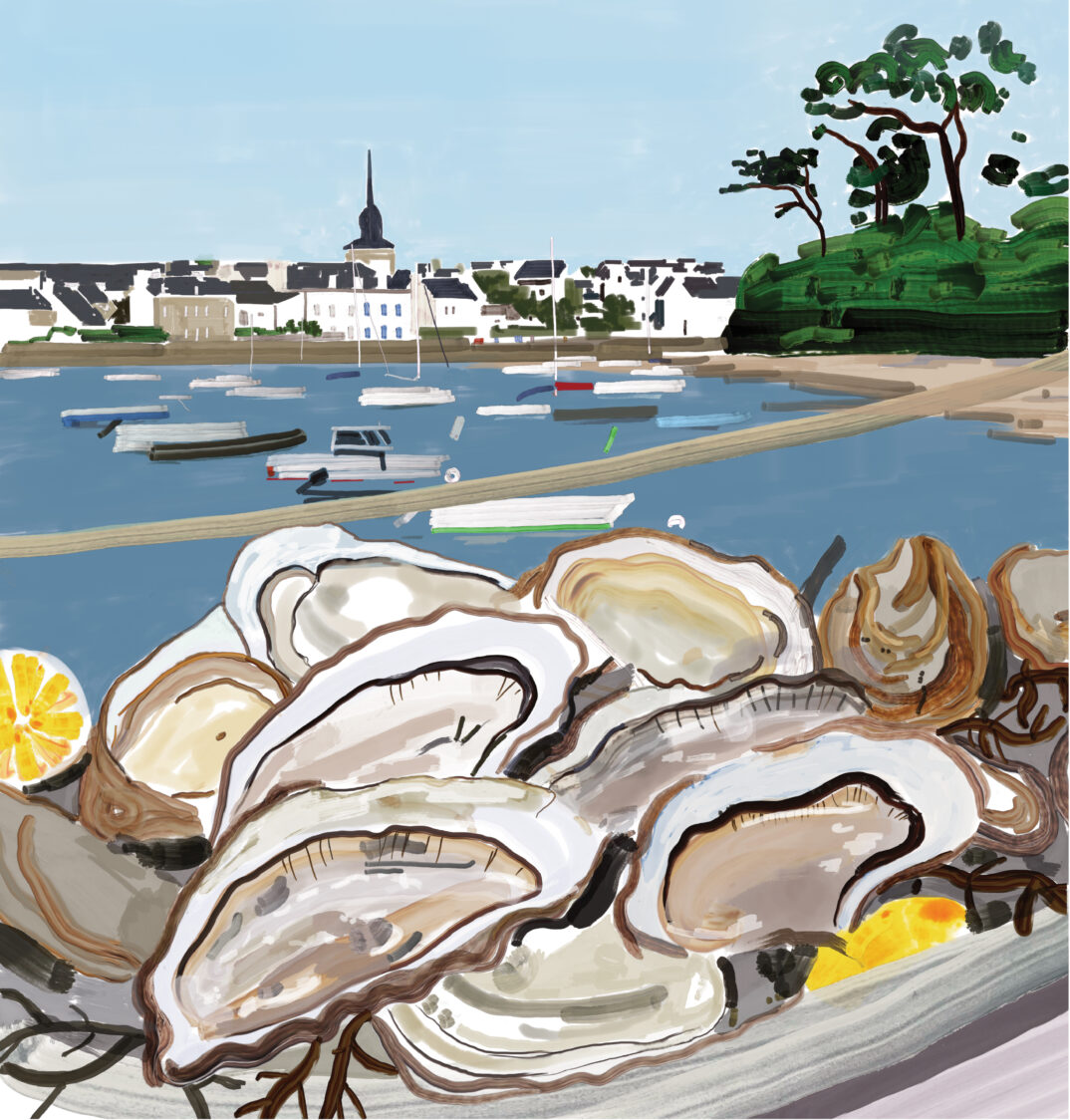

Watercolors by Annabel Briens for Harper’s Magazine

That summer we lived in two houses, one after the other. I had remembered it as two summers, but my brother, Gabriel, reminded me, no, it was all one summer, 1961, when he turned six and I turned eight—a birthday distinct in my memory because of the gift of a small plastic carriage drawn by eight miniature horses, an object of intense fascination that I drove along intricate roadways I constructed in the dirt.

It was a long summer, in any case: long in the elastic time of childhood, and so long it might as well have been two. There were the two houses, after all. As I learn now, consulting Joseph Blotner’s doggedly calendrical biography of our father, Robert Penn Warren, we lived in the village of Locmariaquer on the southern coast of Brittany from May to July, 1961, in a house called Le Brénéguy; we spent July, August, and the first ten days of September thirty-two kilometers to the north, in the ground floor of what Blotner calls a château but that I remember as an imposing country house, a manoir. I didn’t need Blotner to remind me that we were in Brittany because our mother, the writer Eleanor Clark, was planning a book about oysters. Oysters dominated our lives, all those lyrical months.

Le Brénéguy. It floats up in my mind’s eye only in bits and pieces. It was a large house set off from the road and shaded by trees, with fields—open meadows rather than tilled land—stretching away into a great flatness. Of the house itself I remember little: tall windows I now know to call “French,” a pelt of leaves covering the stone façade, cold flagstone and tile floors, a general feeling of grayness, of chill, and of looming, dark, oaken wardrobes and chests. For breakfast, Gabriel and I sat on stools at the kitchen table covered with oilcloth and drank our chocolat from bowls, ample and warm in our small hands, and we ate tartines, crusty hunks of baguette slathered with butter and apricot jam and good for dunking in the cocoa. Nothing like our American breakfasts of Rice Krispies and Cheerios. Strings of onions hung from a hook in the white plaster wall. A small wooden crucifix hung there as well, bearing its small, tortured bronze god.

We had a car: I suppose our parents rented one for the summer. Every few days we ventured into town. Gabriel and I trotted beside our mother from the boulangerie, with its dizzying aromas of fresh bread; to the épicerie for cocoa, coffee, tea, sugar, flour, oil, and who knows what other grown-up necessities; for cuts of veal and poultry to the boucherie, where dead rabbits and plucked chickens and sometimes whole naked, roseate pigs hung on hooks in makeshift crucifixions. If we were lucky, our mother would veer into the pâtisserie, where we would ogle the éclairs au chocolat and mille-feuilles, considering at length before settling on a voluptuous treat.

Locmariaquer had narrow streets with hardly a rim of sidewalk, if sidewalk at all; the buildings were of gray stone, with cobalt-blue shutters and roofs of blue-gray slate. It was a country built of granite. The church rose blockily, like a small fortress, except for the hypodermic needle of the steeple. Most impressively, we might see Monsieur l’Abbé, the priest, striding down the street with his black cassock flapping around him, his squat, round, black hat squished on his head: a vigorous man with a kind face whom I meet again sixty-three years later in the pages of The Oysters of Locmariaquer, the book our mother wrote.

Weekdays were structured, for Gabriel and me, around our attendance at the village school. We were in the room for the younger pupils, a crowded chamber with long rows of wooden desks, several children to each bench. All the older children were taught in a different cavernous hall. Later, I often wondered why our teachers were nuns, and why a large crucifix faced us from the front of the room, up by the blackboard and next to a limply hanging French flag. But only now do I learn, reading my mother’s Oysters, that Locmariaquer had two schools, one Catholic and one run by the state, and that we were in the one supervised by the overworked abbé.

A round hole in the gouged and graffitied surface of the desk accommodated each student’s ink bottle. How grown-up I felt, removing my own ink bottle each morning from my satchel and nesting it in its hole; and even more grown-up, maneuvering the slender lever on the side of my plastic fountain pen so that it would suck up enough ink for me to write with.

The classroom resounded with snickers, whispers, giggles, snarls, and whoops from the children, and furious commands from the two nuns who gesticulated—quite ineffectually—up by the blackboard, and sometimes, in exasperation, charged down the aisle between the desks to punish a miscreant. That happened to the little boy who sat next to me: one nun swooped on him like an enormous crow and yanked him right up out of his seat by his ear. His howl was shattering.

Since my brother and I couldn’t understand French, no one expected us to follow the lessons. We sat in the midst of the tumult. And part of thetumult was linguistic. Our schoolmates were the children of the local oyster workers, fishermen, and farmers, and they spoke Breton. But Breton was outlawed at that school; French was supposed to prevail. Sometimes a Breton phrase overheard by a nun precipitated a flurry of her swirling black habit, a barked reprimand, and a smack to the side of the head—the boys’ heads often shaved, I think to prevent lice.

And what was I writing? My mother had given me one of the great gifts of my life: a medium-size yellow spiral-bound notebook on whose ruled pages she had written, in block letters, my French lessons. I was to study and copy these day by day. And I did. There were the simple conjugations: J’aime, tu aimes, il aime . . . And the simple, usable phrases: Bonsoir. Bonjour. S’il vous plaît. Il fait beau. Comment allez-vous? Le chien. Le chat. I didn’t know it then, but she was laying out the basic structures of reality: Who did what, and to whom, and when? And she was introducing me to a language that would become my second home. I’ve kept that yellow notebook all my life.

I’ve also kept her Breton books, the volumes she pored over while writing her oyster book: collections of Breton folklore by Anatole Le Braz and Florian Le Roy; Théodore Hersart de la Villemarqué’s fantastical reinventions of traditional Breton songs; Henri Waquet’s treatise Art Breton, with its black-and-white photographs so detailed I can almost imagine myself standing again on the Gothic porch of the hillside church in Locronan, or in the crooked nave of the cathedral of Quimper. But perhaps the most informative, in a creepy way, is a little yellowing paperback entitled Histoire de Bretagne, by Alain de Cleuziou and Charles de Calan, first published in 1910. It was a school text, for use in Catholic schools. It comes bristling with the “Approbation” of the bishop of Saint-Brieuc and Tréguier (towns on the northern coast of Brittany), and earlier “Approbations” by a cardinal and by the archbishop of Rennes.

In 1910, France was in an uproar over recent anticlerical legislation that had led to the closure of many Catholic schools and monasteries. But Brittany is a land saturated in Catholicism: “There is perhaps no other country in the world with so many saints,” assert the authors of the Histoire. In his “Approbation,” the bishop of Saint-Brieuc and Tréguier mourns the temper of the time when the book first appeared, “a period of outrageous centralization when Power regarded the Little Country [i.e., the province] as an affront to the Great Country.” “Thank God, times have changed,” he declares triumphantly in this new edition, which my mother read and marked with her pencil. It was published in 1941, when France was in the grip of the Vichy regime.

Brittany wasn’t considered part of France until 1491, when Anne de Bretagne married the French king Charles VIII, and even then, it technically remained an independent duchy until Anne’s daughter, Claude, formally ceded it to her husband, the French king François I, in 1532. The region has a long history, before and after 1491, of resisting French authority. It also remains intensely Catholic, a faith that absorbed older traditions of druidic and Arthurian folklore and enchanted fountains. The Breton Chouans fiercely opposed the French Revolution. These two strains, Catholic fervor and resistance to a centralized nation-state, run through Cleuziou and Calan’s little Histoire, and in the 1941 edition mingle with elements of Marshal Pétain’s Vichy ideology (Travail, Famille, Patrie) that suited Breton piety and provincial patriotism. La patrie, for loyal Bretons, is Brittany, not France. The authors instruct teachers who will be using this text that “nationhood is above all formed by the sequence of human generations following in succession on the same soil and having lived a common history; history is the catechism of patriotism.” Addressing students, the authors intone, “My dear children. . . . All of us as we are, united in our traditions by the bonds of blood and race and by a long History, we form one people. The History of Brittany!”

The Bretons are a people, and Brittany is a distinct place with a distinct culture, though not in Vichy’s ideological sense. In 1961, sitting on the crowded bench in the schoolroom in Locmariaquer and shyly jostling around the paved courtyard with the rough but friendly village children during recess, I had never heard of Pétain. But I was rapidly absorbing the feel of living in an ancient place. For one thing, there were menhirs and dolmens all around us.

Who had erected these enormous stones? We’d come upon them as we walked in the fields. The menhirs rose straight up, crude towers hacked from granite, taller than our parents. I didn’t know the word “phallic” then, but that’s what they were. They were untended, disregarded; sheep and cows grazed around them. When I returned to Locmariaquer decades later as an adult and a parent myself, fences had been built around the larger ones, and an ice-cream stand offered its wares nearby. But in my childhood they just stood about as part of the rural landscape, like natural outcroppings. The dolmens, too: they were like gigantic picnic tables—a stone slab upright at each end with a larger slab laid across like a tabletop or roof. And sometimes the larger dolmens did seem to be roofs, with stones and earth piled around them to form what might have been a tomb. Locmariaquer is famous for these megaliths. One of them, the giant broken menhir called Er-Grah, lies in a field in four pieces like four beached whales. Taken together, the stone weighs, by some estimates, 330 tons and was put up around 4700 bc in a fabulous feat of engineering.

“Neolithic”: that’s all we seem to know about these prehistoric people. Those who became modern Bretons were the Celts who migrated from Britain around the fifth century bc, driven by who knows what pressures. Cleuziou and Calan maintain the fantasy (derived, I suspect, from the nineteenth-century Breton scholar Ernest Renan, who had a soft spot for the folks he called “Aryans”) that these Celts came “from Asia.” Not likely. The schoolbook historians are on stronger ground when they claim that Breton is a Celtic language akin to modern Welsh and Irish. Another wave of Celts came over from Britain in the fifth and sixth centuries ad to escape Picts and Saxons and other pillagers; some of these peripatetic Celts were the saints I heard about as a child, like St. Gildas, St. Cado, and St. Ronan, who all sailed over to set up monasteries and hermitages and are still celebrated in local festivals and pardons, Breton ceremonies honoring important local saints.

It’s hard for me to separate, now, the tales of saints I imbibed long ago from my mother, from the stories I’ve read since then in the books she collected, and from my visits scattered over the years to Breton churches where the saints still conduct their adventures, bluntly carved in stone. Brittany teems with stories. Those early Christian heroes confront witches and tame wolves and resurrect the dead, and many aren’t even recognized by Rome. My mother loved the witch stories. She told them to us; later I read them in her oyster book, and at greater length in Le Braz and Le Roy. There was St. Guénolé, the son of an emigrant from Britain, founder of the first Breton monastery and friend of King Gradlon of Quimper—who only became king of Quimper, according to many tellings, after his witch of a daughter, Dahut, stole the key to the sluice gate of his island city, Is, and let the sea flood in. As Gradlon fled on across the causeway on horseback with Dahut riding behind him, Guénolé, on the shore, hurled a curse, and the king cast off his daughter. She fell into the waves and became a mermaid, and the whole city drowned. Of her, my mother writes, she was:

an equally familiar type of witch, the classic nympho, good-looking, sex-crazy, and sick in the head, and she probably wouldn’t amount to much if there hadn’t been a saint in the picture.

Elsewhere, she remarks, “It’s hard to be a first-class witch without a saint nearby to keep you stimulated.” The sex-crazy diagnosis, obviously, she didn’t offer to us as children.

Even as a young child, I felt bewitched by these Breton stories, the way they took on a life of their own. We saw them all around us, in the stone carvings in the village church; in the bits and pieces of local lore that came our way; dramatically in the carved granite calvaries depicting the Passion of Christ that punctuate Breton country roads and sometimes are found outside parish churches, along with side chapels, ossuaries, and elaborate porches and arches. Some of these calvaries, like one of the oldest, at Tronoën, near the seashore southwest of Quimper, assemble an enormous cast of actors. From the Nativity through all the key scenes of the Man-God’s life, death, and resurrection, the stiff figures act out their parts around the massive rectangular base of the monument, rising to the central characters on and around the cross that crowns the whole and pierces the sky. The large calvaries, caught up in the grand rhythm of the story, have several hundred figures. But the ones I remember around Locmariaquer were simpler, cruder, though no less dramatic. The whole countryside was alive with story.

Martyrdom hung in the air, and was made grotesquely real to me that summer of 1961. Brittany still remembers the savagery of the civil war provoked by the French Revolution, like the mass drownings in Nantes of thousands of suspected royalists. I remember it, too, in my own way.

St. Anne, the mother of the Virgin Mary, is one of the great patron saints of Brittany, more important in some ways than Mary herself, and her sanctuary is in Auray, several kilometers outside Locmariaquer. The annual pardon of St. Anne celebrates her in a tremendous festival of bagpipes, prayers, dancing, cider, and crepes. Auray is famous also for its Carthusian monastery, the Chartreuse, built in 1382 to commemorate those who died during Jean de Montfort’s victory over his distant cousin Charles de Blois for control of Brittany in the Battle of Auray in 1364.

We had gone, late one afternoon, to visit the Chartreuse. Jean de Montfort and Charles de Blois meant nothing to me, nor did I harbor any particular feeling for St. Anne, or for the French Revolution, for that matter. It was already dusk when we drove up to the imposing hulk of stone that remained of the monastery. An old lady in a black dress—she seemed ancient to me—rattled a huge key ring and led us into the large, dank chapel, which looked pretty much like most other chapels, with its side altars and plaster and wooden saints. But then she led us outside, and with one of the heavy iron keys, she creaked open a heavy door and ushered us down a few stone steps in darkness. Her hand reached out and flipped an electric light switch. I heard it click.

At once, the crypt—for that is what it was—was flooded with green light, and what leaped into view was a tremendous mass of human skeletons. Stacks and stacks: skulls, rib cages, arm and thigh bones, pelvises, all gaping and glaring. The scream that broke out of me almost levitated me. I can feel the shock of it even now. I was still screaming as my parents hustled me and my brother back up the steps and into the now darkening parking lot.

Those bones belonged to the “martyrs” of the massacre of Quiberon, victims of the French Revolution. In July 1795, an army of around five thousand men, led by French royalists sailing from England, landed at Quiberon, the tip of the peninsula west of Locmariaquer (and one of the best places in the world to raise oysters, by the way). Thousands of Chouan counterrevolutionaries on the mainland joined them in a plan to attack the Republican army of the coast. But a terrific muddle in the invaders’ plans and a conflict between their leaders resulted in their being trapped on the peninsula. Many fled by sea; many were killed; more than six thousand were captured. Of these, around seven hundred and fifty were condemned by revolutionary tribunals and shot, many of their bodies flung into trenches in a field at Auray now known as the Champ des Martyrs. Their remains were dug up at the start of the Bourbon Restoration in 1814; by 1823, after the excitement at Waterloo, the royal regime, now back in charge, built the chapel and installed the bones in the crypt where they terrified me out of my seven-year-old wits and gave me nightmares for years.

We were in Brittany for oysters, not for skeletons and crypts. Locmariaquer and the region around it, Morbihan (“Little Sea” in Breton), produce what many consider the most exquisite oysters in the world, les plates, in an elaborate process that takes three to four years, a centuries-old procedure of seeding, transporting, and tending to which our mother devoted her book. For my brother and me, this meant long afternoons wandering along rocky shores and skipping oyster shells across the shallows while our mother talked with the bosses of the chantiers and with the workers, men and women who had grown up in the oyster business and given their lives to the hard work of maintaining the barges, laying out thousands of tiles for the oyster larvae to settle on, monitoring tides and temperatures, and all the other tasks required to make oysters happy. Locmariaquer is a port. I’m probably mistaken, but it seems to me that most of the streets led to the waterfront with its cafés and its docks, its bustle of fishing boats and, in the full swing of summer, small pleasure craft, sailboats and motorboats. But the main business was oysters.

The people we came to know in and around Locmariaquer, the people who turn up in my mother’s book, worked superhumanly hard, caring for children and gardens and elderly relatives and at the same time laboring at the oyster farms, or fishing, farming, or running small shops. But they also entertained themselves. We attended a pardon: it must have been for St. Anne d’Auray, of which all I recall is a large, milling crowd of people in traditional costumes, especially the women with lace coiffes on their heads, the small ones in the Morbihan style, not the towering white columns from around Quimper. Most exciting, though, was the circus. This little enterprise came to town and plastered posters all over the walls. It was run and staffed by one family, who set up their ring in the village square. We had seats on folding chairs right up against the border of the ring. A clown with a great red ball for a nose lurched around declaiming—in English!—“to be, or not to be,” the first time I had heard those words. The father, in a black frock coat, cracked his whip at a mangy and irritated lion who eventually agreed to jump through a hoop. Then a dappled horse cantered around the ring with a young lady in a sequined leotard—one of the daughters—graciously standing on tiptoe on its back; as the horse snorted its way past our seats, it lifted its tail and let fly a large, greenish blob of manure right over the low barrier and into my lap.

In July, we moved to the manoir, the country house some thirty kilometers away. We had the whole ground floor. The owners, whoever they were, seemed to be away: we never saw them. I remember nothing about the interior, but I recall distinctly the tall stone façade; the gravel drive in front; the huge lawn sweeping down from the house to a tidal inlet filled, at low tide, with a pungent black mud called la vase. La vase, our parents warned us, was dangerous. It could suck us in and swallow us: we were absolutely not to venture down the hill by ourselves. And I remember the forest. The house was surrounded by fifty acres of woods: beech, oak, chestnut, magnolia. That’s where we took our exercise, long family walks in the afternoons. It was on one of those rambles that Gabriel leaned down to pick up what he thought was a piece of rusty iron. He was just about to grasp it when it swiveled away into the bushes. Hullabaloo from our parents: he’d almost seized a viper. Between la vase and the viper, life was beginning to feel dangerous, but also more interesting. Gabriel turned six that July, and I turned eight: old enough, we thought, to survive.

Many people didn’t survive, we were gradually coming to see. Those skeletons in Auray! Now that school was out, our parents took us sometimes to an immense beach, not a tidal inlet. Here the full Atlantic Ocean growled, and we shouted and romped in the dark waves. Our father, a powerful swimmer, would churn far out from shore until we could hardly see him. The dunes rose behind the beach like small Saharas to meet the adjoining fields. And here, too, a dangerous past imposed itself. Along this mighty sweep of beach, stationed at regular intervals, brooded German “pillboxes.” These concrete bunkers, some as big as cottages, hunched over the shoreline. You could, if you were feeling brave, enter them through a passage in the rear, on the landward side; they were dark inside and stank of urine. Paper trash and old bottles cluttered the way. Something evil had taken place here, we could tell from the grim way our parents looked at them and spoke of them.

By September, our mother had gathered enough intelligence about oysters to begin writing her book, and we returned to our American lives. But it turns out that my impression of two Breton summers wasn’t entirely wrong. The next summer, in 1962, we spent mostly in the south of France, in the Basque country at the foot of the Pyrenees, close to the border of Spain. Beverly, a tall, slender, young American woman, came along to take care of us so our parents could work. We rented a large house right next to the working farm outside the village of Ascain, near Saint-Jean-de-Luz. Our kitchen door opened onto a narrow strip of terrace and the low stone wall separating us from the farmyard. Here, as we sat at the oilcloth table drinking our chocolat, the door stayed ajar and chickens hopped over the wall to cluck around, pecking for crumbs on our stone floor. And Gabriel and I hopped back over the wall, often, to play with the farm children. They spoke French and Basque; from them I learned the one Basque word I remember: hartz, “bear” (though they pronounced it arza).

At the tail end of this summer, we returned to Brittany for a few weeks so our mother could check up on oyster lore. But the Basque summer matters to me for other reasons. It’s the summer I began to learn, more seriously, not only that the world could be dangerous, but that I could be.

The first sign of danger came from the Atlantic Ocean. We had gone swimming at the crowded beach at Saint-Jean-de-Luz—nothing like the vast, lonely Breton beach, but a teeming, populated, colorful, noisy human festival of umbrellas, sandcastles, beach towels, bikinis, and waffle vendors. I was paddling in the surf when suddenly a wave hoisted me up and smacked me against a rock. I ran crying from the water with my right arm dangling at an odd angle, already swelling and turning blue. A scramble to a doctor’s office: X-rays; a broken elbow; a plaster cast. No more swimming for the rest of the summer. But that was only the beginning. A couple of weeks later, I suddenly couldn’t swallow and could hardly breathe, and had a high fever. Another trip to the doctor: mumps. I spent what felt like weeks blearily in bed, where I began to read French in volume after volume of Astérix and Tintin. Then, one after another, everyone in the family came down with mumps—Gabriel, then our father, then our mother—which was terrifying, since the adults got so sick they could barely walk, and seemed delirious: I remember our father wobbling down the hall, trying to reach the bathroom. Beverly, providentially, seemed immune, and she must have cared for us all through that dreadful time, not quite the babysitting vacation near the beach she had signed up for.

Our parents were neither immortal nor all-powerful—that was bad enough news. But just as vividly came signs from the outside world. When we recovered from mumps, Gabriel and I played in the grassy yard in front of “our” house, behind the ivy-covered stone wall that protected it from the road. I remember both of us looking up, day after day—and I imagine we were looking south, since we could see mountains—and seeing paratroopers floating out of the sky in their parachutes. They swayed down mesmerizingly. Wave after wave of them. They were just training, we were told.

And worst of all, perhaps, the inner world. I don’t understand it, but I discovered in myself, that summer, a spirit of destruction that seemed utterly unlike the little person I thought I was. I can rummage for explanations: Was it because of a broken arm and mumps and frighteningly sick parents? I don’t know. But one afternoon, when no one was paying attention, I walked down the road past the fields on either side. Not far away, a family on vacation had set up their tent and parked their small trailer in a meadow I suppose they rented from the farmer. No one was at the camp. Their washing hung on an improvised laundry line; a few pots were neatly stacked by a little gas cookstove set among stones. I don’t know what possessed me: I knocked down the laundry line, I kicked over the pots. Then I fled. It was furtive, mean, and pointless. By the time I’d returned to our temporary home, my spirit felt darkened. I knew something about myself, now, that I wished I hadn’t known.

By the end of that Basque summer, our parents had regained their strength and we spent our few weeks in Brittany at yet another rented house. What I recall most is our trip to the airport in Paris to return to the United States. To make sense of this memory, I’ve had to read Julian Jackson’s biography of Charles de Gaulle and other works about the Algerian War. It’s still hard to understand what we experienced. Because instead of seeing traces of long-ago dramas—prehistoric dolmens and menhirs, bones of French royalists from 1795, German bunkers from World War II—we drove right through a scene of contemporary politics for which our parents, to my continuing amazement, seemed unprepared.

In those two summers of ours, 1961 and 1962, France was in a furor over its war with Algeria, and on the verge, or several verges, of civil war. Of this, I had no idea. In May 1958, when de Gaulle was in retirement, the French government almost fell to a coup d’état because of the military’s determination to keep Algeria French. The army revolted in Algeria, invaded Corsica, and fifty thousand paratroopers were set to descend on France when the panicked government called de Gaulle back to power to avert the putsch and design a new constitution—the Fifth Republic. By November 1960, President de Gaulle had had enough of trying to hold on to Algeria. On November 4, he spoke on television of an “emancipated Algeria.” He launched a referendum, and his government began secret meetings with the Front de Libération Nationale (FLN), the movement for Algerian independence. The large population of French pieds noirs, many of whom had lived in Algeria for generations, and a sizable portion of the French army went into a frenzy. On April 22, 1961, a week before we left for France on a Pan Am jet from New York, four retired generals led an insurrection: with regiments of the French Foreign Legion, they took over the city of Algiers and were prepared to invade France. Squads of paratroopers were ready to fly. (Those paratroopers! Floating down so gently over the Pyrenees . . . ) De Gaulle, in his general’s uniform, gave an electrifying speech on television urging France to resist the coup: “Françaises, Français! Aidez-moi!” (“Frenchwomen, Frenchmen! Help me!”)

The coup collapsed, but all that summer, while we played by the menhirs of Locmariaquer, the Algerian drama boiled. De Gaulle pursued talks with the FLN in Évian, and the unsuccessful French rebels had formed a radical group, the Organisation Armée Secrète (OAS), to spread terror in Algeria and in France. They almost managed to kill de Gaulle with a bomb on September 8, 1961, two days before we flew back to the United States. The FLN began shooting policemen in Paris; the Parisian police responded with a massacre of Algerians, attacking a peaceful demonstration and throwing as many as several hundred bodies into the Seine (to this day, no one seems to know exactly how many died). All that winter the French government and the FLN negotiated in secret, and on March 18, 1962, an agreement was signed. A referendum was approved by 91 percent of French voters; in July 1962, while we suffered from the mumps in Ascain, Algeria became an independent nation. And all hell broke loose: The OAS murdered more Algerians; pro-independence Algerians murdered pieds noirs. On the evening of August 22, 1962, as de Gaulle, his wife, and his son-in-law drove out of Paris, two cars ambushed them in the suburbs with a storm of gunfire (and a carload of explosives that didn’t go off). It seemed miraculous that no one was killed or even wounded.

And where were we? We left France at the end of August, a week after this second attempted assassination. I remember our driving through Paris, our car loaded with luggage. Our mother was at the wheel, our father sitting by her in the passenger seat. She was normally a good driver, but she must have been nervous, as the car kept bucking and stalling. Our father murmured something helpful. “Goddamn it! I’m driving!” she shot back. Beverly, Gabriel, and I were crammed in the back seat. What strikes me most, looking back: The stone-faced soldiers lining the streets, holding machine guns. Olive-green military jeeps. I’ve peered into the online archives of Le Monde for those dates: there’s the story of the attack on de Gaulle, but nothing about soldiers in the streets. Still, with the OAS on the warpath, maybe it was normal to have soldiers on the alert? That scene is imprinted in my memory, but I remember nothing else about our journey home.

My mother’s book, The Oysters of Locmariaquer, came out in 1964 and won the National Book Award. It’s a story about oysters, yes. But when I look into an open oyster—and I have learned to eat them, even North American oysters—centuries come tumbling out. From the mother-of-pearl gleam of the inner shell and the gobbet of sea flesh with its black, lacy fringe rise druids and crucifixes, saints and wars and revolution, Chouans and machine guns, as well as gardens and bowls of hot cocoa. And the disquieting knowledge that I, too, carry wars within me.